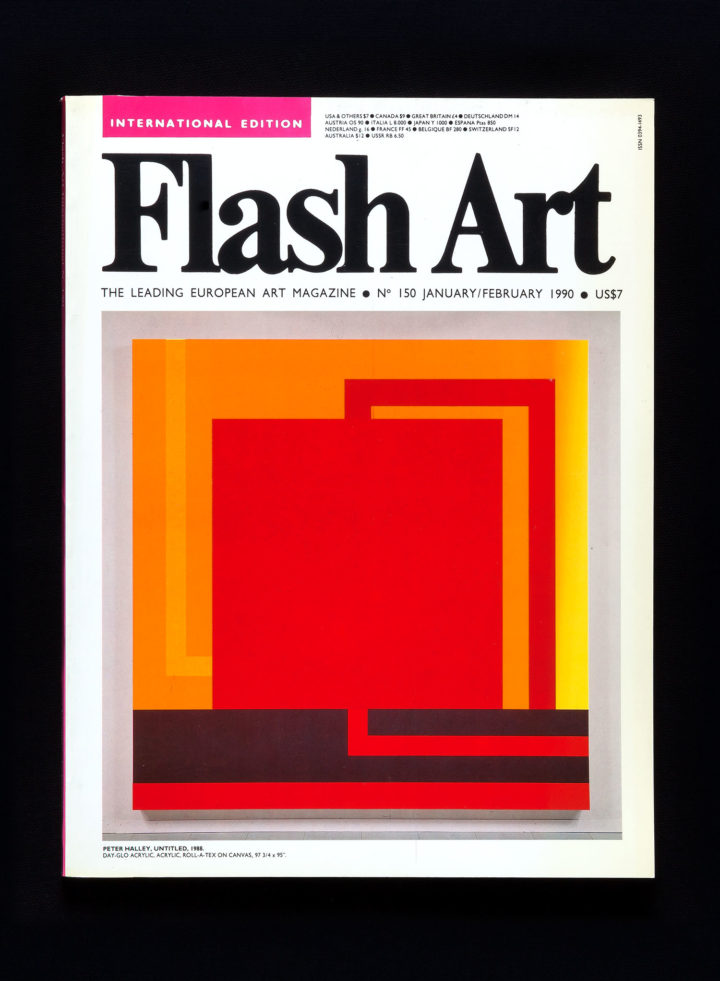

Peter Halley has been among Flash Art’s most celebrated artists, with a formidable career that the magazine has followed closely since the mid-1980s. Not only an accomplished painter but also an incisive theorist, her Halley compiles a selection of his writings from the decade when digital technology conquered the world.

Peter Halley has been among Flash Art’s most celebrated artists, with a formidable career that the magazine has followed closely since the mid-1980s. Not only an accomplished painter but also an incisive theorist, her Halley compiles a selection of his writings from the decade when digital technology conquered the world.

1981

Robert Smithson insisted that artists must be conscious of the motivations that guide their work, of their role in society, and of the role their work plays. He insisted that artists must try to describe what they believe to be the nature of reality and not be seduced into creating escapist “dream worlds” (either pleasant or haunted). He claimed that artists who are “dumb enough to think they’re on a cloud or something” actually serve to reinforce reactionary political values by reiterating social and political illusions in the dream worlds they create.

1982

Our culture is increasingly seizing the opportunity to “simulate” (in Baudrillard’s terminology) the crucial powers that were assigned to nature’s dominion — the power of thought, repeated in the computer, which “realizes” bourgeois dualism; the ability to create life, accomplished chemically and mechanically; and the ability to create space itself in the binary circuitry of computer-animation devices. Thus, the circle of thought is finally completed; the world is made to refer back only to itself.

Yet a number of troubling questions are provoked by recent art practices influenced by post-structuralism. First, there is the question of how artists can address the world of the simulacrum. If, indeed, the post-industrialist world is characterized by signs that simulate rather than represent, how can an artist communicate this situation? Is it possible to represent a simulation? If not, it only remains for the artist to engage in the practice of simulation himself or herself. But by so doing, an uncertain situation is set up. The practice of simulation by the artist can be seen as an endorsement of the culture of simulacra. But one wonders if such an endorsement is desirable if, as Marxist critics believe, post-industrial culture constitutes a further level of social alienation.

Finally, one finds oneself turning away reluctantly from post-structuralism’s promise — its potential for sweeping away the mythologies of so many deceptive humanisms — to a consideration of what negative results it may engender. For, ultimately, post-structuralism, whether Baudrillard’s, Foucault’s or Barthes’, cannot be separated from certain misinterpretations to which it inherently gives rise. To misinterpret post-structuralism is to arrive at a single reality, the reality of power — not the power with which one class controls another, but the single remaining power to understand and manipulate the codes.

In so many sectors of contemporary society, including perhaps the present art world, the successful manipulation of the codes to gain social power is treated as if it were a life-or-death matter. To acknowledge only the existence of language has created an unfortunate limitation on the range of actions that are thought to make sense.

The final image that emerges from these reflections is the image of destruction. One thinks of the Second World War, that “natural disaster” brought about by social players, and shudders at imagining the torrent of destruction that may be unwittingly released by the inhabitants of our own empire of signs if, in their attempts to gain power over the codes, they unleash forces beyond everyone’s control.

1984

Jeff Koons’s work also deals with the state of things within this simulacrum. New Wet / Dry Triple Decker (1981) takes as its model certain characteristics of Minimalism, reflecting the nostalgia for style, the circularity of signs that defines the simulacrum. But in Koons’s work, the production-oriented signifiers of Minimalism (steel, industrial paints, etc.) are replaced with elements (the appliances, the Plexiglas boxes that are like display cases) that draw attention to consumption. While Minimalism sought to reveal structure, Koons displays appliances whose workings are hidden behind smooth plastic and enamel surfaces. Within these display cases, he has created an environment of almost complete cleanliness and order. The vacuum cleaners themselves are completely pristine, and each Plexiglas surface is perfectly cleaned and polished. Koons’s pieces have the same effect on the viewer that Baudrillard has described the space program as having on the public. Koons, like NASA, has created a universe “purged of every threat to the senses, in a state of asepsis and weightlessness,” a universe in which we are “fascinated by the maximization of norms and by the mastery of probability,” where, as in contemporary social organization, “nothing will be left to chance.”

1985

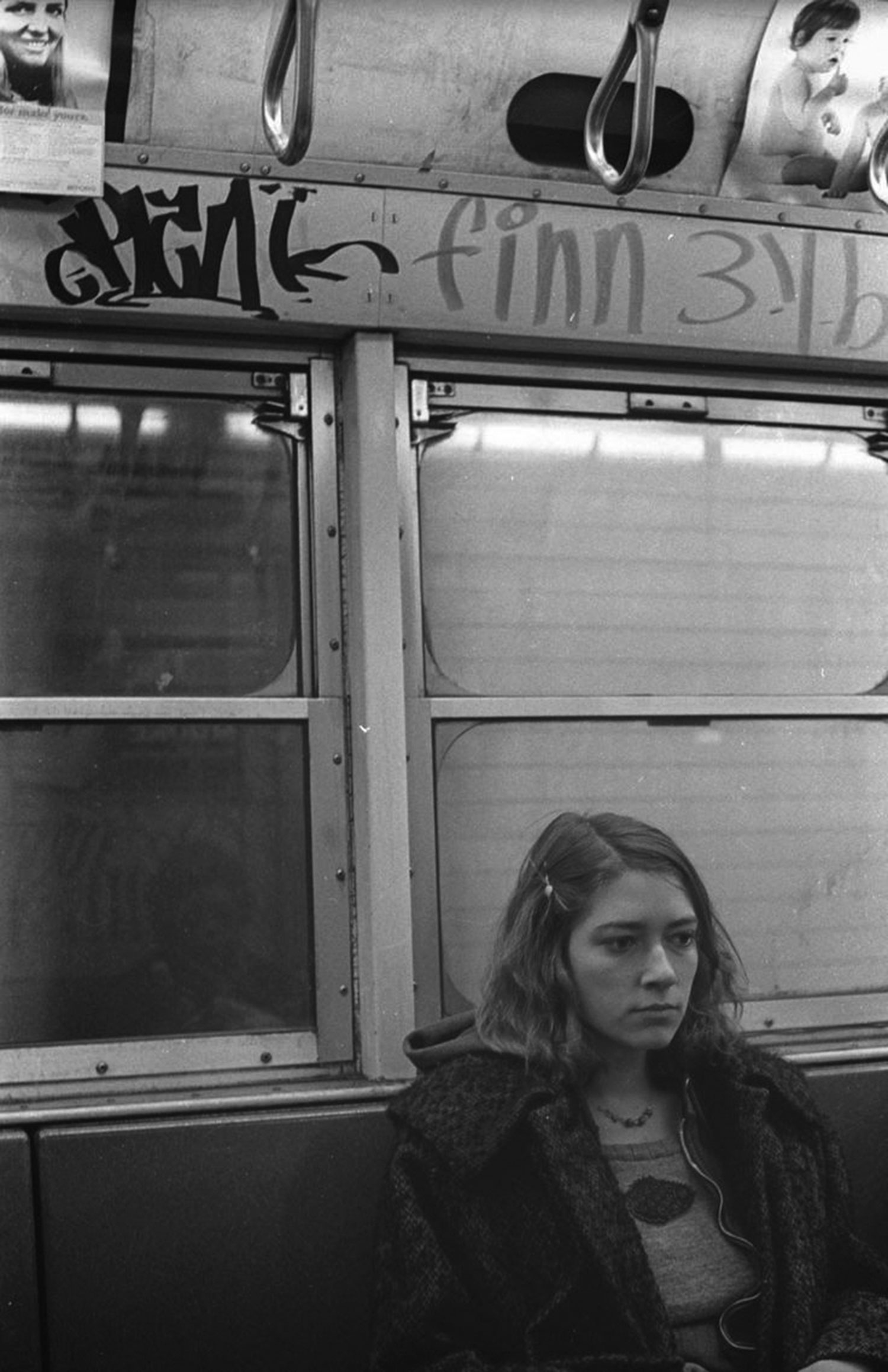

The cell. Its ubiquity reflects the atrophy of the social and the rise of the interconnective. At the same time that the advent of piped-in “conveniences” has made it unnecessary to leave the cell, it has also made it impossible to leave the cell. One finds oneself stuck at home waiting for a phone call; instead of entering the social, one must stay within the cell to communicate with someone else. Or one stays at home to watch something on TV; in order to be entertained or informed by human beings on television one forgoes the presence and company of actual human beings. One enters another cell, the automobile, to travel from the cell — and the automobile too is increasingly being outfitted with communications equipment to make it a desirable place in which to remain.

The semiconductor chip conforms to this same model of two-dimensional planar circulation. Gradually, just as the social has been transferred onto this schema of highways and malls, so are memory and knowledge being transposed onto these miniature circuits. The stimuli of the modern world — sounds and sights — are also reproduced and distributed through endless systems of linear technology. All visual and aural information — speech over the telephone, the television picture, computer data — is encoded into lines of electronic information. The linear becomes language. The arcane discipline of the electronic now guards the gates of the senses.

The proliferation of the computer is the development that most insures the closure of this system. In the computer, we see physically affirmed, as if by an independent source, all the assumptions of linear thought. Conversely, the computer ignores all utterances not made according to the rules of its own linear code. With the advent of personal computer use, the computer becomes an oracle of instruction in the structures of the linear. It gives instruction in how to write and how to conduct business — but according to its own linear rules. It is even deployed to indoctrinate children into the ways of the linear. Further, as greater and greater amounts of society’s information (both financial and intellectual) are stored in computers, even the reluctant are coerced into dealing with the computer and its pattern of thought.

1986

On the grid, there is only the presentness of unending movement, the abstract flow of goods, capital and information. Everything is exchangeable. Nothing can be remembered since everything can be replaced. Existence is defined only in terms of position. If position is lost, existence vanishes. Memory becomes information as it is pushed onto the grids of electronic and photochemical recording. Here, time-past and time-future are pulverized by the esoteric mechanisms of entertainment-culture. We gaze at a film still, made last year, of a 1932 movie depicting a future that is already past. The young actors are old or dead. The costumes of the future are old-fashioned. Past and future cancel each other out in this temporal equation, leaving only the present remaining.

We are convinced. We volunteer. Today Foucauldian confinement is replaced by Baudrillardian deterrence. The worker need no longer be coerced into the factory. We sign up for bodybuilding at the health club. The prisoner need no longer be confined in the jail. We invest in condominiums. The madman need no longer wander the corridors of the asylum. We cruise the Interstates.

We are today enraptured by the very geometries that once represented coercive discipline. Today children sit for hours fascinated by the Day-Glo geometric displays of video games. Adolescents are enchanted by the Cartesian mysteries of their computers. As adults, we finally gain “access” to participation in our cybernetic hyperreal, with its charge cards, telephone answering machines and professional hierarchies. Today we can live in “spectral suburbs” or simulated cities. We can play the corporate game, the entrepreneurial game, the investment game or even the art game.

1987

The time has come to stop making sense — to replace History with myriad exaggerated theories of post-, para-, quasi- and super-. History has been defeated by the determinisms of market and numbers, by the processes of reification and abstraction. These form the great juggernaut of modernity that has destroyed History by absorbing it, by turning each of History’s independent concepts to serve its own purpose. Another kind of response is then called for. Ideas that themselves change or dissipate as they are absorbed, that are formed with the presupposition that they will be subject to reification. Only a rearguard action is possible, of guerilla ideas that can disappear back into the jungle of thought and reemerge in other disguises, of fantastic, eccentric ideas that seem innocuous and are so admitted, unnoticed by the media-mechanism, of doubtful ideas that are not invested in their own truth and are thus not damaged when they are manipulated, or of nihilistic ideas that are dismissed for being too depressing.

It is not generally acknowledged to what extent each individual is tied to these grids of computer communication. But the telephone line is an endpoint in a huge electronic network that enmeshes the entire globe. More importantly, credit cards, which are replacing the relative autonomy of currency, tie huge segments of the population into a kind of slavery of computer debt. One is lured into the system with the promise of a “credit line,” the ability of the “user” to spend the computer money any time and any place. But, if the payments are not made, a kind of passive wrath comes down on the user, who is banished from the system and the grids. That is to be left as helpless as an excommunicated Christian in the Middle Ages.

Thus the social is finally becoming the site of “pure abstraction.” Each human being is no longer just a number, but is a collection of numbers, each of which ties him or her to a different matrix of information. There is the telephone number, the social security number and the credit card number. The financial markets, those huge arenas of abstract warfare, have completely detached themselves from any relationship with the material world. Currencies float. National boundaries crumble.

I wanted to redefine geometry as something that was in the world, that had a history, and that was tied to issues of power and control. I wanted to show that geometry was not simply classical beauty, but that the use of geometry was fundamentally linked to the goals and objectives of certain groups at certain times.

1990

I have come to believe that this world of the technocratic and the rationalized has become self-enclosed and totalized. We have reached the state in which this ideology has become so dominant that it is inescapable. There are important symptoms of this all around. First of all, the symbolic and the technical have become the same. In the nineteenth century, we still had the image of the priest and that of the doctor, one filling the spiritual role and the other the technical. In our culture today, the doctor has basically won. The doctor becomes the priest, as does the scientist or the psychologist. We have also seen Western technical thought reach an unprecedented state of hegemony across the planet. This process has accelerated dramatically in the last twenty or thirty years, with technocratic thought coming to dominate the cultures of Asia as well as those of Europe and the Americas.

And lastly, we have the hegemony of the computer. This is something that has very much concerned me on an experiential level. Almost all knowledge is stored in computers nowadays, and almost all communication is mediated through the computer. However, I think we are totally unaware of the impact of this level of mediation in our lives. Further, the computer represents a final concrete realization of Cartesian thought — it is abstract thought made “real.” The Cartesian universe of duality, zero and one, and of horizontal and vertical axes, which had until mid-century been only an abstract notion, is today made real and is physicalized in the computer.

There is one reason that an interest in geometry in painting can still be viable — because geometry is also the language of the managerial-professional class. It is the language of the corporation and of flowcharts; it is the language of urban planning and of communications. If we can look at geometry in modernist art critically, I think we can begin to critically analyze our assumptions about our own language as members of that class, rather than simply trying to critique the language of other classes and subgroups in our society.