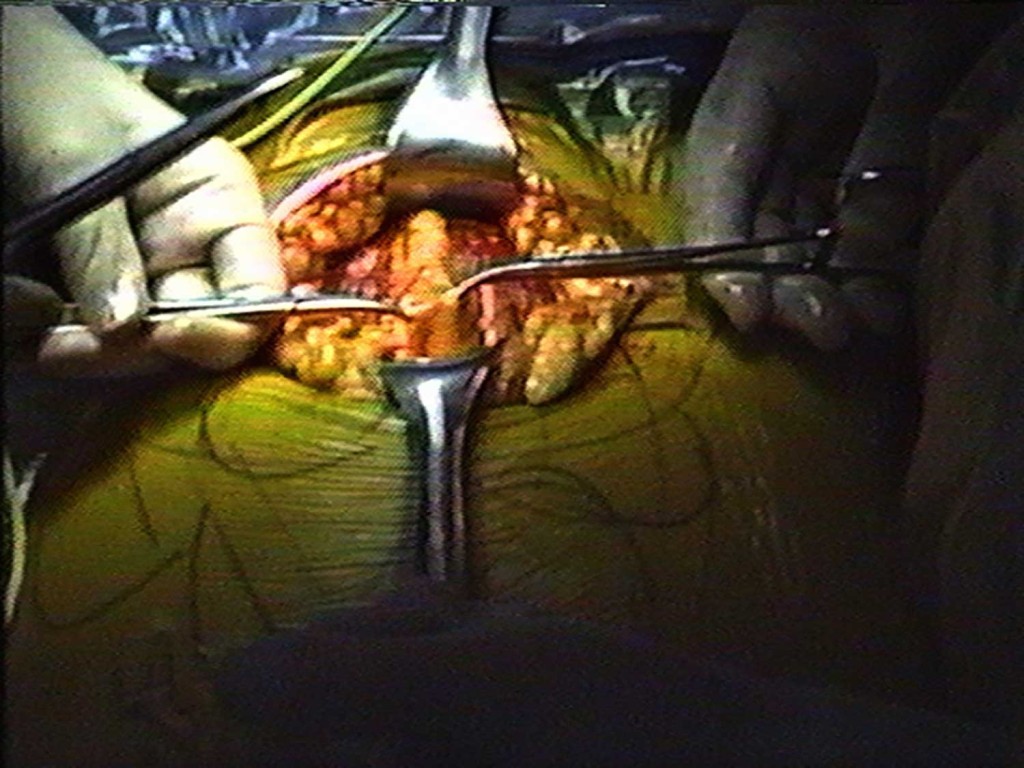

Imagine walking into a gallery and seeing a skewed flat screen on the floor, its surface illuminated by a video of what appears to be a glimmering, unearthly landscape of deep reds and purples. This is Huge Uterus (1990), an artwork by Berkeley-based artist Lutz Bacher. Over her four-decade-long career, Bacher has gained a reputation for (both being and) making art that is enigmatic and rather elusive. The video documents a nearly six-hour surgery the artist underwent to have fibroid tumors removed from her uterus, the prone monitor mimicking the horizontal surgery table. Her new-age surgeon made such tapes for patients to watch in their post-procedure sedative haze, to help them understand the trauma their bodies experienced. Bacher requested a copy to use as an artwork — her early video works are not dissimilar in length and unedited presentation (its title, Huge Uterus, is borrowed from a notation in her medical file). The piece can be described as a meditation on bodily distortion and trauma that invokes the legacy of body-centric feminist art while repelling the squeamish in the process. Yet it is the work’s complete decimation of personal privacy that is most disquieting. Now, after all of this, imagine encountering the work and feeling nothing.

Is it not curious for an artist who made her insides visible (to name just one clear example) to often be repeatedly charged with, as many writers have contended, making art that is meaning-avoidant? It is true that Bacher’s genre-defying practice doesn’t always readily give up its motivations. And yes, an all-encompassing reticence to provide context on Bacher’s behalf is certainly palpable. Yet even when Bacher plucks an object from an obscure location — a dumpster, a thrift store — and places it in an art gallery with Duchampian verve, it seems safe to say that Bacher isn’t attempting to upend artistic conventions. Bacher rends objects from their original sources and implications and watches the ensuing rupture of “meaning,” as with Boyfriends (2006), a pair of male mannequins who appear to be in the midst of embracing. Personal significance and political commentary are partially buried in Bacher’s work, forcing the viewer to grasp at conventional notions of artistic value, questioning themselves along the way. After all, “Lutz Bacher” is a pseudonym, and a maladroit one at that with its vaguely masculine, Teutonic sound, further destabilizing the dependability of meaning in her work.

The first two and a half decades of her career are largely populated by artworks that contain political and feminist threads, though they quickly unravel: a snippet from a high-profile rape trial on a loop, Xeroxes musing on Lee Harvey Oswald. Since the late ’90s, Bacher has been making artworks that are less engaged with unconventional consciousness-raising; in recent years she has often been accused of withholding information, whether it’s the absence of a press release or the replacement of one with a recipe for butterscotch pudding. This point is belied not only by Snow, her recent exhibition catalogue/raisonné, which illustrates and describes hundreds of works, but also by her publications and projects that entertain the idea of being diaristic. Bacher has also given primacy to the plainly visible, as in Books for People (2011), variable stacks of “books for people to take away & do a book report,” and the portable archive The Betty Center (2010), which made sought-after information regarding her early practice available for perusal.

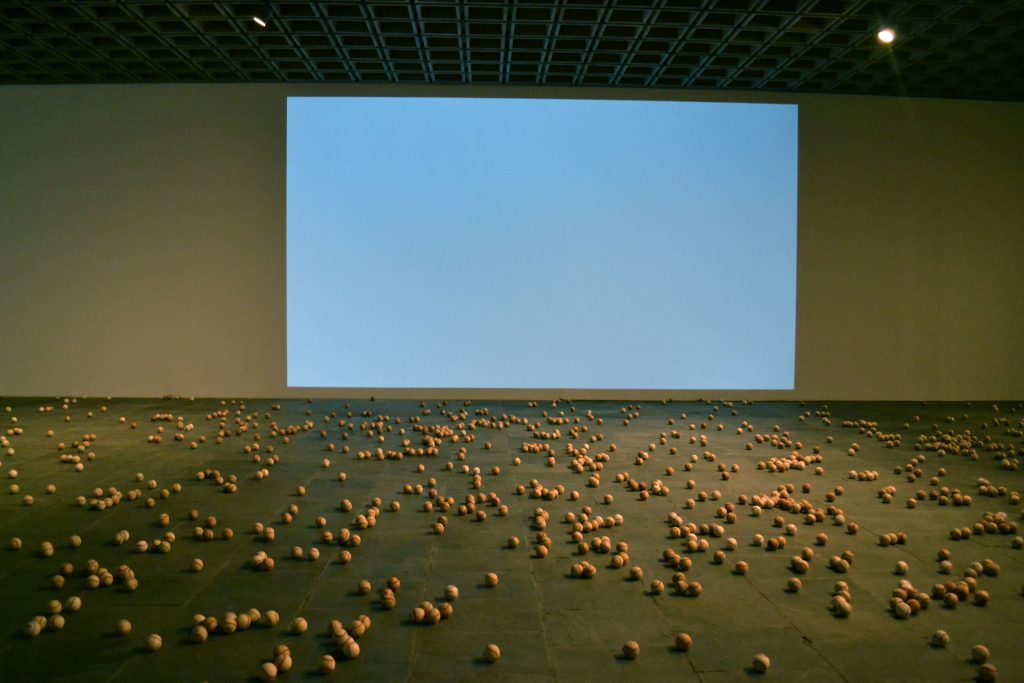

In recent years, Bacher’s environment-scaled works have proliferated, seeping from one gallery into adjacent ones, dominating them with ease. During the 2012 Whitney Biennial, a field of ragged Baseballs (2011) dotted a wide swath of the fourth floor of the museum, the venerable keeper of the legacy of American art, poeticallyspeaking to a sense of national specificity. From its inception, Bacher’s art has roamed quite freely — across photography, sculpture, conceptual idioms, installation, sign-painting, found materials, video and so forth. Her consistent yet laissez-faire “sampling” of material culled from the nether regions of society(the exact source often being moot or too uninteresting to report) stands apart from the rigid practice of appropriation propagated by her Pictures peers.

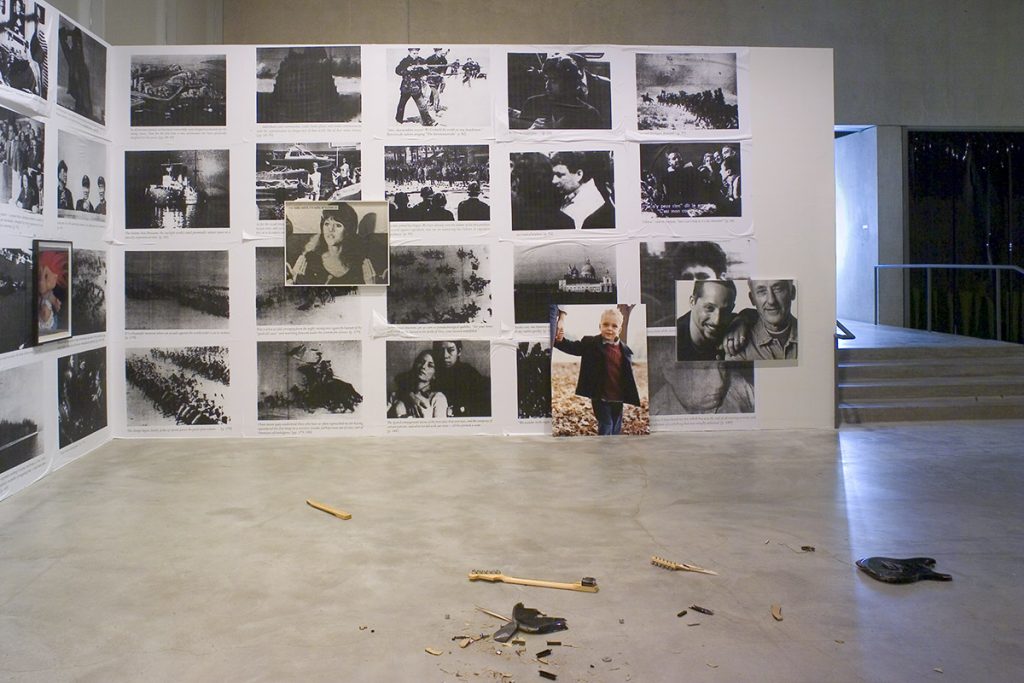

Looping and tripping over themselves in large series, Bacher’s longest-reaching practice, her photographic works, often burn through their source material slowly, leaving the viewer with the cooling embers of a (stranger’s) fragmented memory. In fact, they’re often crumpled or crumbling, or in the case of Spill (2007) wrinkled under a brown stain, though it isn’t always clear whether they were found this way or simply made with slipshod facture. In one instance, Bacher accidentally ran over a print with her car and used it in an exhibition anyhow. An example of Bacher’s hazy engagement with the politics of looking, Men at War (1975) follows a group of shirtless post-adolescents — one is adorned with a navy cap and a painted swastika on his chest — posing coyly on a beach, not a battlefield, across twenty black-and-white photographs reworked from one found image. Yet the photographic is only one means of Bacher’s examination of re-presentation, not to be confused with an interest in mechanical reproduction.

Despite her engagement with many artists as we will see, Bacher rarely dips into the shallow end of the contemporary art-history pool, yet in occasionally doing so she uniquely challenges ideas of the hallowed art experience. A Dan Flavin artwork, pink out of a corner (to Jasper Johns) (1963), made by Bacher in 1991, emphasizes in its deadpan singularity what may be Flavin’s questionable winking at Johns’ sexuality rather than representing a nonchalant traipsing into the territory long-claimed by the equally critic-confounding conceptual artist Sturtevant. A lighter example of Bacher’s casual invocation of art-adjacent subjects can be found in Bushwick (2013), a crappy painting on plywood named for the Brooklyn neighborhood where many young artists hold studios.

The phrase “magnificent perverseness” (as coined by Caoimhím Mac Giolla Léith) comes to mind again and again regarding Bacher’s oeuvre perfectly governing the full spectrum of her output, from intimate details to politically charged references to slightly off-center pop-cultural allusions. Magnificent perverseness also helps to explain the gray territory in whichBacher’s audience resides, unsure if the artist is critiquing society’s acquisitive impulses or documenting them, regurgitating the most banal aspects of everyday life or showing us how to transcend them. Perhaps she is devilishly trading fragments of herself for capital. However, the perverse thing is, Bacher nimblydoes all of the above.

Do You Love Me?began as a 1994 video of interviews led by Bacher with fellow artists, curators and friends. They were conducted by Bacher so that the subjects could reveal what they think of her — she seems to take a certain pleasure in saying “now let’s get back to me.” The work was revived in 2008 as an ongoing project and a tome of an artist’s book published in 2012. It’s been said many times over that the interviewees reveal more about themselves (and their insecurities, which Bacher so ably draws out) than the artist, yet the amorphous project inevitably shores up aspects of “the personal” through fragments that would otherwise remain partially hidden: her family life, her “real name,” even the personal motivation behind certain works. Within Do You Love Me?, various aspects of her oeuvre (the repositioning of found material, personal details cut adrift from their context, aesthetic decisiveness, obsessive tendencies) are present while remaining perfectly dubious — after all, how is one to know what has been edited out or augmented?The interviews mirror Bacher’s difficult-to-discern operations, revealing in part not why she does what she does, but at least how.

In a gesture that curiously fuses self-reflexivity and affection, Bacher’s most intimate works center around her then-art dealer, the esteemed and fabled gallerist Pat Hearn. The Playboy paintings, Bacher’s inaugural exhibition at Hearn’s gallery in 1993, are arguably Bacher’s most conventionally alluring works to date. Alberto Vargas’s ’60s illustrations for the “gentleman’s” magazine were sign-painted atop a primed ground, the voluptuous ciphers with their come hither gestures and bedroom eyes accompanied by demeaning quotations. One reads: “Sure, I’m for the feminist movement. In fact, I’m pretty good at it.” We are able to know how the exhibition looked and how the gallery felt through Bacher’s video tour of the exhibition (which she makes for most of her exhibitions), including Hearn saying hello to the camera.

Documentation of an insistent kind, surveillance, is a thread that runs throughout her oeuvre. From October 1997 to July 1998, Bacher installed a video camera aboveHearn’s desk, transmitting a closed-circuit live feed of her daily activities to a hallway monitor. After Hearn’s death, the footage was rendered into astop-motion animated video, Closed Circuit (1997–2000), with Bacher abbreviating some moments — unrecognizable faces appear and disappear within seconds — and poignantly lingering on others: a lively conversation between Hearn and Armory co-founder Matthew Marks, Hearn eating a meal, Hearn sticking her tongue out at the camera. From watching the tape, Bacher’s admiration for this profound figure and friend in the midst of treatment for cancer seems rather clear. To describe the work as full of pathos is not enough. Unlike, say, one of Andrea Fraser’s gallery talk videos, Closed Circuit doesn’t give the impression of contemporary art as having a cyclical nature; instead, through content and form (the choppy sequencing of the stills), it deftly gives voice to the instability of all things.

As in much of Bacher’s work, these private affairs, not fully divorced from their origins, are skewed by both their transposition from one medium to another and the relocation from actuality into the art institution. Art historian Carrie Lambert-Beatty coined the term “parafiction” in order to help her unpack and sort through an unwieldy artwork by Michael Blum that tenuously straddled actuality and the imaginary. According to Lambert-Beatty, parafiction maintains a fictive element while also presenting some notion of the real; in short, parafiction isn’t fiction, but it cannot be called notfiction. This “in-betweenness” equally applies to Bacher’s work, which so often emanates from her first-hand experiences, although Lutz the person can only be known through shards of her fragmented self, at best. We could call this the parapersonal or even the “Lutzian.” This notion alludes to the moments that haven’t been completely separated from Bacher or her lived experiences; they have been estranged, not from Bacher, but the viewer, who is left attempting to receive information that has been scrambled in the process of transmission.

The 2008 catalogue Smoke Gets in Your Eyes includes photocopies of e-mails sent from Bacher’s friends describing encounters that made them think of Bacher’s work or something that was particularly “Lutzy.” After witnessing an exhibition by Bacher it’s hard not to happen upon various Lutz Bachers in the outside world. As the artist Monica Majoli elegantly stated (in a once-private e-mail published by Bacher): “I often see the world as a found photograph by you.” It isn’t that Bacher makes us reconsider the culture, people and products that surround us in our day-to-day routines; it’s that she makes all of it questionable. By forcing the engaged viewer to only somewhat trust her as a person (who they will truly never know), Bacher is free and able to do that which only the people we think we know can: make our ideas of the everyday and ordinary, what we are most sure of and familiar with, unstable.