“We come from a heavily colonized country where they adopted Christianity. I saw the way [my grandmother] navigated her relationship with that God. I saw all the parts, they were all already indigenous there. It wasn’t part of a pagan conflict or a pagan antithesis to that faith, it was her being already. The way she prayed, the way she spoke, the way she evangelized, was already an indigenous mode of contact and being that we would call pagan in this modern world. But it’s not pagan, it’s really just a mode of being that is so resistant to the colonized sovereign mode that it survives it without even any acknowledgment or any need for that resistance, because its resistance is already irreducible. Its resistance comes out of its irreducibility to coloniality.” — Elysia Crampton, Dazed, 2016

“Identity is a push-and-pull kind of term; queer people tend to roll their eyes at it, but it’s a thing of survival.” — Elysia Crampton, Dazed, 2017

Notions of identity and (non) belonging are, today more than ever, permeating the mainstream art industry as a response to the systems of oppression that increasingly threaten its marginalized communities. Expressing a specific sense of self through art is a form of healing, especially if said communities are diasporic and/or living under systemic hegemonies that alienate/dehumanize them. This process is more an act of survival, bonded to communities’ common history and memory, and even if it cannot be detached from their own territories, sometimes the purpose goes beyond the colonial horizon of taxonomy. Moving through Elysia Crampton’s works, representing more than a decade of activity as a Native American multidisciplinary artist, one can easily outline why her oeuvre is one of the most pivotal in the field.

Her understanding of personhood, land, and queerness from the Quechuaymara — Quechua and Aymara indigenous communities of the Andean region between Peru and Bolivia — perspective, is already — and has always been — a form of resistance, as it was shaped out of an irreducible narrative that does not acknowledge colonial restrictions. Despite the socio-political radicality attributed to most of her work, Crampton reminds us that a contemporary approach to postcolonial theory in art comes from a position of power: “My problem with getting lumped into these worldings,” she says in a 2015 Tiny Mixtapes interview, “particularly with online/consumer groups, is that even the ones taken as the most futuristic, and therefore thought of — by default — as optimistic, feel mired in colonial ideas of execution and seem to blindly carry out the functions of a system that privileges this mode of educated whiteness that takes its own prejudices as an unspoken given.” What has characterized her visual and musical works since the very beginning of her career is an oversaturation of sound, images (physical or rhetorical), history, soil, and flesh — but not in a manner recognizable by subject, citizen, or settler (Lubner, 2019), as it cannot be reduced to their anthropocentric immanence.

Crampton navigates nonlinear dimensions of time and space. She finds in errors, chaos, and the irrational a place where anti-coloniality and queerness are kept alive. Her art is as irreducible to coloniality as indigeneity itself: the way she unapologetically claims her queer and Aymara becoming uplifts the experiences of those who still were/are caught in-between Western categories of being. Many of us brown/queer folks can never be grateful enough for what she and her music has meant to us.

Crampton has defined her work as “folk music,” foregrounding its primordial meaning: music tied to a constant (re)definition of identity through memory, history, and past/future continuity. From early times to the present, evocations of huayno, cumbia, saya, caporal, and Huancayo styles have helped our Andean community, living in and out of diaspora, thrive. Her music made me feel seen. It made me want to heal the wounds that colonialism had inflicted on me my whole life — wounds I previously lacked the capacity to see.

A press release once defined her style as “an adoption of sonic dialects across the Americas [that] shape the way different communities hear not just sounds but frequencies.” Blending all possible combinations of Andean melodies and rhythms, Mexican cumbia sonidera, Brazilian funk, Angolan kuduro, noisy R&B edits and other oddities, the complexity of her output was unique. Crampton influenced a whole new generation of producers, DJs, and performers, creating a nonlinear space/time in which the people of the Abya Yala — “Latin America” in the native Kuna language — could survive and heal.

Elysia Chuquimia Crampton is an Amerindian artist, composer, and writer of Aymara descent, currently based in Southern California. Her interdisciplinary investigations — into Andean tradition and cosmology, trans resistance and liberation, sovereignty critique and carceral abolition — are expressions of her own Aymara becoming-ness. Her Aymara legacy is rooted in the Bolivian Andes, where her maternal family is originally from, and where she lived in early 2016, at her grandfather’s farm in the village of Rosario, province of Pacajes, La Paz.

Overall, her journey throughout the US and Abya Yala has been a nomadic one: being born in the Inland Empire, in outer LA, she grew up between Mexico and Southern California, in an Adventist household. As a young adult she first lived in LA, where her first music project, E+E (pronounced “E and E”), took form in 2008. Early releases included Bound Adam(2011) and Promise (2012), which were mostly sound collages of lo-fi, experimental R&B, pop, and heavy metal. In an interview from 2012 she defines her eclectic approach to music production as “a grave robber stealing limbs from here and there, to throw them on this slagheap and muck them into a new beast.” With this early, almost anthropophagic approach to sampling, Crampton had already embarked upon an intimate journey of sound, flesh, and soil that would eventually lead to her seminal debut LP The Light That You Gave Me To See You and the mix El Sueño del Forastero(2013). This is when her first strongly Latinx/Andean and spiritual references emerged out of the chaos, giving us a glimpse of a new — and yet ancient — flourishing becoming-ness.

Between 2012 and 2015, Crampton moved to Virginia, to the 2,500-inhabitant town of Weyers Cave. It was here, in 2015, that she had the chance to craft her EP masterpiece American Drift for Blueberry Recordings. The album, is an exploration of what she has defined as her experience of brownness “beyond culture, as geology,” as an Andean two-spirit woman in the context of Virginia’s own colonial history. Identifying as a body “dwelling between colonized and colonizer” (Rodriguez, 2016) has helped Crampton navigate land/soil on a geological level. The resulting four tracks are warm-hearted soundscapes built on layers of cumbia and caporal percussions, looped with atmospheric recordings. As Nishnaabeg academic Leanne Betasamosake Simpson says in her book As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance (2014), indigenous people don’t relate to the land by possession or control over it, but through connection; “a generative, affirmative, complex, overlapping, and nonlinear relationship” with the land (Simpson, 2019) is exactly what Crampton has been investigating in American Drift. As she remarked in an interview in 032c last year, “The notion of stone is something that is prevalent in our daily lives because of geography and praxis, becoming part of the languages we signal — chemical, tactile, textual, textilic, iconographic, oral, etc. That affiliation with stone, with all of its becoming, all of its generativity — all of these things come into play and that’s a long history that also created me. The stones are my family and my ancestors, a shared becoming, a shared story.”

As the EP became more and more acclaimed by the international press, Crampton’s intimate approach began to attain global visibility. Each track functions as a whole synesthetic experience, claiming continuity between Virginia’s Spanish colonial past and her own, using sound and melody to narrate brown geographies through her brown body. Tracks like “Axacan” or “Petrichrist,” based on the etymology of petrichor, the Greek word signifying the scent of the rain, are some of Crampton’s most powerful artistic and political statements.

“The gift the ancestors have given me is this body,” she explained to 032c. “The body is also a legitimate document. I’m not just saying that through the experience of having been a body summoned to appear and be present in a court of law, within the US legal system. I am saying that in the face of a logocentric society that places text as the highest justice, that embeds binary code into the attention/image economies we navigate. I’m still not sure what all of that means for the future (and the past), but in Aymara there is this term q’ara that translates to ‘being bare,’ and is used to refer to someone with no-belonging.” Her relationship with her own physicality has grown in tandem with her consciousness of her two-spirit nature, which she prefers using instead of trans “because of the narrowing in what trans has come to mean, specifically in the United States.” What the term highlights is in fact the “already-was” component of the concept, referring to “the indigenous precolonial legacy that her own queerness comes out of” (Crack Magazine, 2016).

Quechuaymara queer history and resistance have been important touchstones throughout Crampton’s artistic development and life journey, coming from a place of systemic marginalization in the US as a brown, two-spirit indigenous woman. Figures like Bartolina Sisa, Ofelia (Carlos Espinoza), Candy, Veronica Bolina, and Lohana Berkins have been vital to Crampton’s survival, and such research and reverence informed her work on Elysia Crampton Presents: Demon City for Break World Records in 2016. According to the press release, the collaborative album is a “solidarity piece” made possible by the “family networks and communities that have inspired and sustained our survival and collective search for transformative justice.” Many friends of Crampton’s were involved in the production of Demon City, such as Chino Amobi, Why Be, Lexxi, and Rabit. It is an epic poem, arranged with the same majestic language of American Drift, but in a more heterogeneous register; every detail, DJ effect, and musical reference is part of a cultural legacy that Crampton has formed a personal relationship with (Amin, 2016). Here the artist is also honoring the memory of Aymara revolutionary Bartolina Sisa, who in 1781 led an indigenous uprising of 40,000 people against Spanish colonizers in La Paz, Bolivia. In 1782 Sisa was not only captured, humiliated, and executed in the main square of the city, but her dead body was cut into pieces and sent to different villages throughout the country, to intimidate any further rebellion. Demon City engages Severo style, a musical genre coined by her friend and collaborator Lexxi to describe “an ongoing process of becoming-with, made possible by the family networks and communities that have inspired and sustained our survival and collective search for transformative justice.” Becoming-with is a fundamental aspect of Crampton’s life and music practice, as it occurs beyond the scientific understanding of physical constitution. Severo music means “claiming our own name,” she says in a Dazed interview. “It’s a way to renegotiate all those things that get lost because people aren’t aware of those legacies. [I am] trying to relocate that kinship network and not let it get lost. Especially coming from a queer perspective, coming from a queer person, as a person of color.”

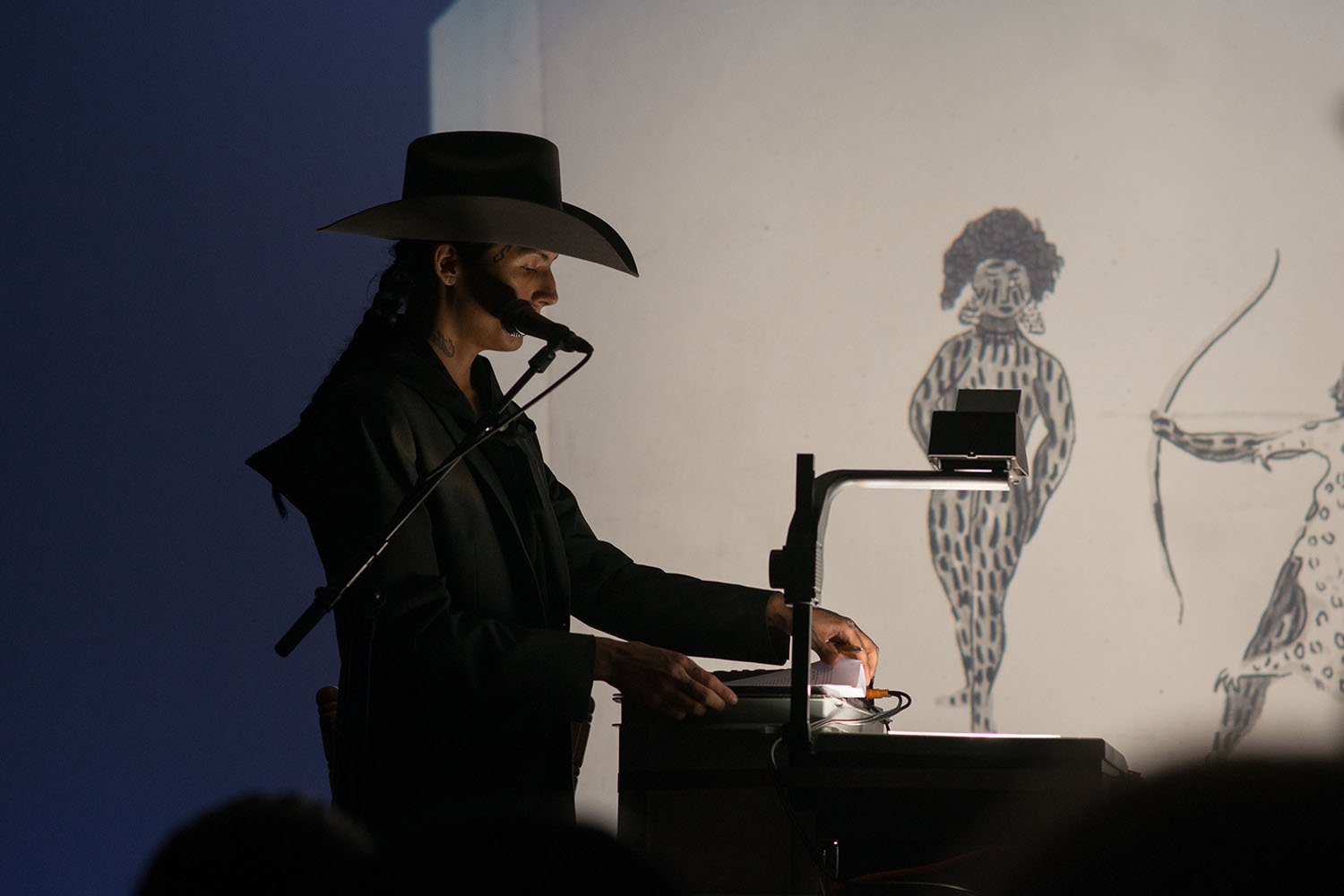

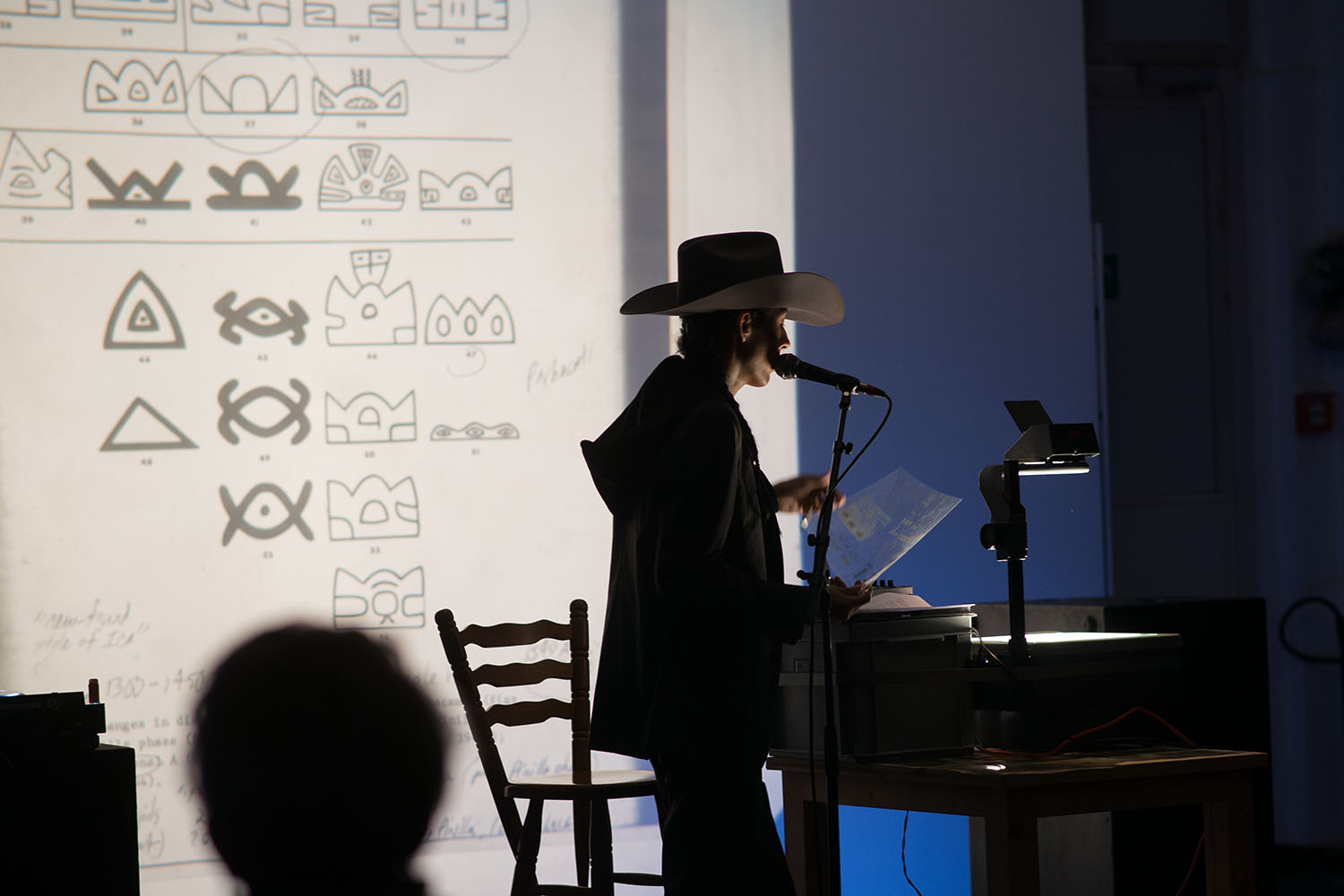

Another influential work by Elysia Crampton, which takes the stylistic premises of Demon City and extends them to a futuristic dimension, is Dissolution of the Sovereign: A Time Slide Into the Future (Or: A Non-Abled Offender’s Exercise in Jurisprudence). It debuted in 2016 as a show that combined DJ production with live performance. The work’s narration is from the perspective of Bartolina Sisa’s severed body. Crampton imagines her spiraling into a distant and utopian future, where the carceral industrial complex had been finally abolished, the earth is almost sterile, and the universe is populated by blind trans AIs of color generated by Sisa’s entrails. The show represents Crampton’s indigenous futuristic contribution to the Aymara/Andina legacy.

After having lived in La Paz, Bolivia, for a while in 2016, Crampton returned to Southern California, where she is still based. Her latest releases have been even more intertwined with traditional Andean cosmogony and theory. The LP Spots y Escupitajo (2017) was dedicated to Chuqui Chinchay, the two-spirit deity who is a “guardian of hermaphrodites and Indians of two natures,” as reported in the Relación de Antigüedades Deste Reyno del Perú by the indigenous Quechua cronist Joan de Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamaygua, circa 1613. Also known as Oscollo, the deity sometimes manifests itself in the form of a feline (an Andean cat/jaguar), and it is a protector of two-spirit, third gender (ipa or orua in Aymara) q’ariwarmi shamans ( embodying masculine, q’ari, and feminine, warmi, natures of humanity) in precolonial Quechuaymara societies. In 2018 she released a self-named LP for Break World Records dedicated to Ofelia – a revolutionary china (“femme” in Aymara) travesti – one of the “mariposas, or butterflies, who forever altered the costume of the china supay in the 1960s and 1970s, the Aymara femme devil performed by queer and trans bodies in the street festivities, which, though now formally Christianised, can be traced back to before the conquest” (E.C. interviewed for TANK Magazine, 2018). The album was also a reflection on pachakuti, the Quechua world-reversal and dissolution of power structures, and taypi, the space/time paradox where dichotomies collide in a “radical asymmetry.1”

Chuquimamani-Condori is Elysia Crampton’s native Aymara name, under which the artist has self-released a free-to-download compilation titled Quirquincho Medicine on Bandcamp. All donations go to the Seventh Generation Fund & American Indian Movement SoCal Chapter. The seven compositions on the release are entirely instrumental, and have been written and performed by Chuquimamani-Condori herself, using a baby grand piano, bombo and wankara (traditional Andean drums), rattles, and a charango (small Andean guitar). As Crampton/Chuquimamani shifts to a more minimalistic and purer approach to her irreducible queer and indigenous art, we, in and out the Abya Yala diaspora, are sure her work will forever be both timeless and specific. This is how resistance is made.