The entire oeuvre of Columbian artist Doris Salcedo is informed by a strong political commitment that relentlessly confronts us with death, grief and memory. The large-scale installation Plegaria Muda (2008-10) on view at Moderna Museet Malmö (commissioned together with Lisbon’s Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation) is her latest poetic manifestation.

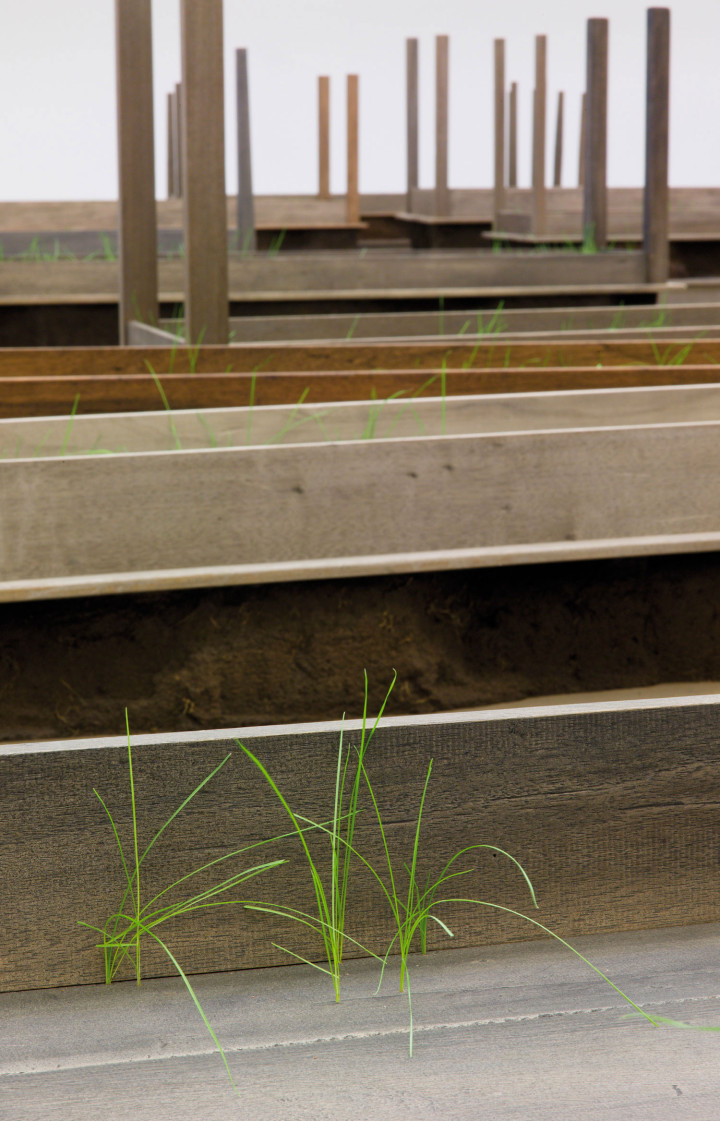

In its largest version the installation comprises 166 units, here brought down to 69, each consisting of two wooden tables, mirrored top to top, approximately ten-centimeters-thick layer of earth to separate each pair, with thin straws of grass sticking up through the tops. They form an intricate pattern: some are left isolated, some almost touch at one corner, others are closely together as if embracing. Tables and chairs from everyday life — bearing marks of people who have lived with these vernacular pieces of furniture — have become a signature of Salcedo’s work. Deceitfully simple interventions are combined to permeate the installation with a sacred atmosphere. Although the tables could be taken as exhibition displays, they remind the viewer of dissection tables, and are the size of funeral coffins. If the sealing of the space’s windows serves to keep out the daylight and close off the outside world, one is simultaneously drawn back to it, where the ghastly events Plegaria Muda must be speaking of take place every year, day, minute.

Mute prayer — that is, Plegaria Muda — evokes images of mass graves, but not as seen on television images from South America in the ’80s and ’90s; from Rwanda in 1994; Srebrenica, Bosnia, in 1995; Germany, Poland and Russia during WWII; or of any of the other places where victims of war deprived of their humanity were reduced to casualties of war. Plegaria Muda exhibits no bodies, no individual’s personal items such as clothes or belongings, yet the sense of individual people is very strong. Each pair is a stand-in for a human being; for a death; for every single death that has occurred in massacres in the past, and for those that will occur in massacres to come. Their repetition does not let the visitor escape. We have to deal with it. And Doris Salcedo is absolutely confident that we can.

The work began as an investigation into the killings that had taken place in the ghettos of Southeast Los Angeles. Salcedo also encountered mothers and families of some of the 1,500 young men from Colombia’s marginalized communities; they were tricked into the army with false promises of work and money, then brutally and systematically murdered by the Columbian Army, who, after killing them, dressed them in guerilla uniforms and presented them to the government as guerilla soldiers killed in combat — what has later been called “false positives.”

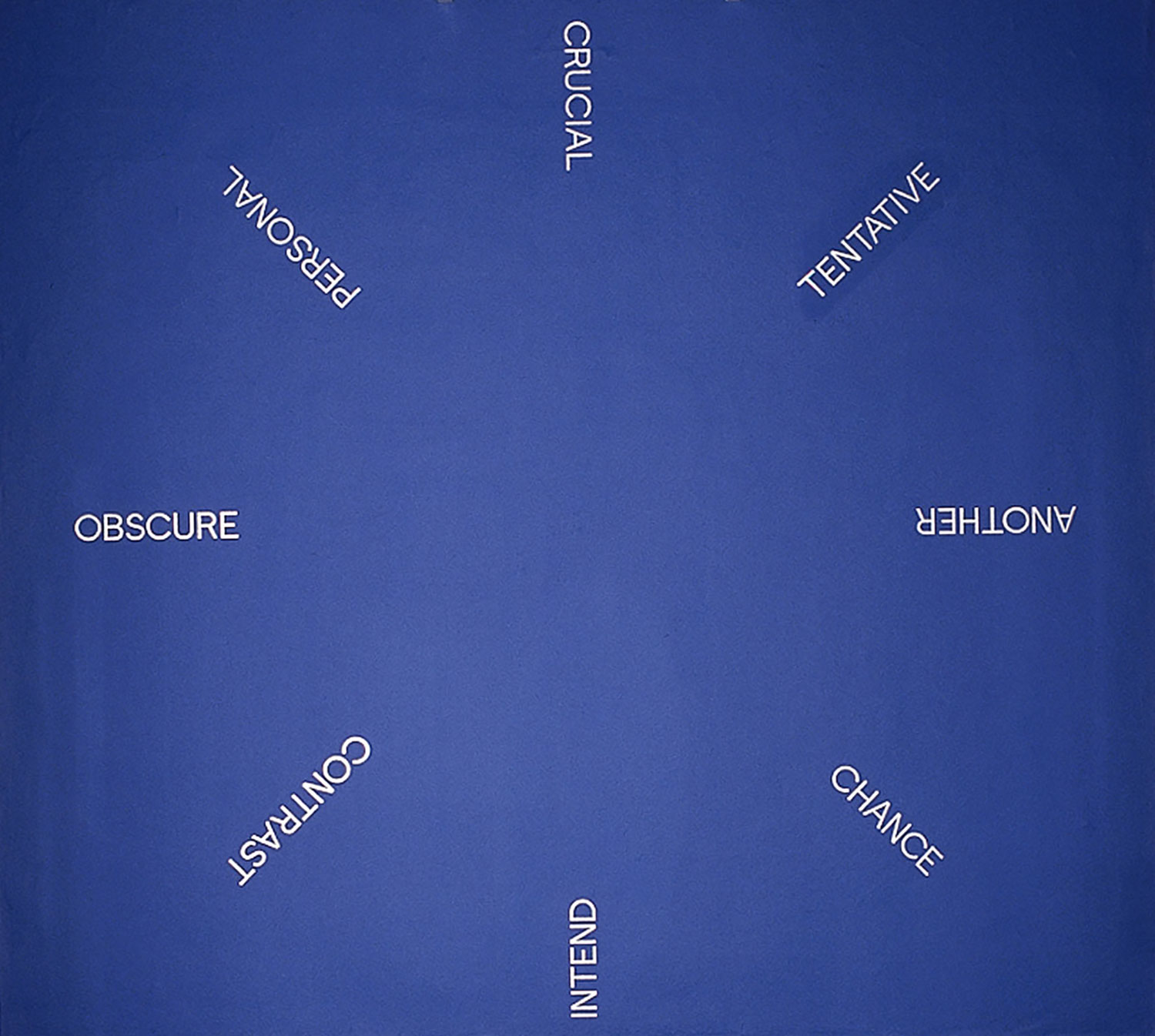

Plegaria Muda is Doris Salcedo’s attempt to restore their humanity. The work is exemplary of her use of the object as vestige: the table pairs are traces of bodies, of actions, and of the passage of time. Time is indeed a crucial element in Salcedo’s work. Both the time it takes to be made and, perhaps more importantly, the time we choose to invest in it. The repetition of the images insists that no matter how long ago a human being was violated, there is still time to recognize and remember what happened. When it comes to the organized murder of human beings, Salcedo does not accept the collective amnesia that pervades society. That is what her prayer may be about.