Since its initiation by the architect and painter Arnold Bode in 1955, Documenta has pushed the boundaries of curatorial frameworks and art- making. Documenta is a large-scale quinquennial exhibition less concerned with the art market than other major exhibitions of its scale (such as the Venice Biennale), instead favoring the platforming of social practices and often radical artistic propositions. Remarkably, it has taken fifteen editions for a group of artists to take the curatorial reins. The word “documenta” was an invented word supposed to demonstrate the intention of every exhibition (in particular the first Documenta) to be a type of documentation of the contemporary world — a world that the German public was not able to see during the Nazi era. Later in this text I will return to this notion of state-regulated visual arts in relation to the unfolding controversaries of Documenta 15 and the organization’s inability to deal with the complexity of recent events.

The collective known as ruangrupa (spelled and written with a lowercase “r”) emerged out of the liberalization of Indonesia following the end of Suharto’s autocratic regime in 1998. Formed in 2002 as a non-profit organization, ruangrupa’s focus of the past two decades has been to foster exhibitions, festivals, art laboratories, workshops, and research in addition to publishing books, magazines, and online journals in urban contexts. The group was invited to curate Documenta 15 by a selection panel of international curators and museum directors. The impetus of this idea came from the selection panel’s desire to not have a celebrated curator but instead to foreground a group of artists who would determine the exhibition participants, thus mirroring the trend to support collectives in the contemporary art world in recent years. The collective invited sixty- seven core participants, mostly made up of more collectives, mainly from the global south. It seems that one can obtain only an estimate of how many artists are involved, with that figure being close to fifteen hundred.

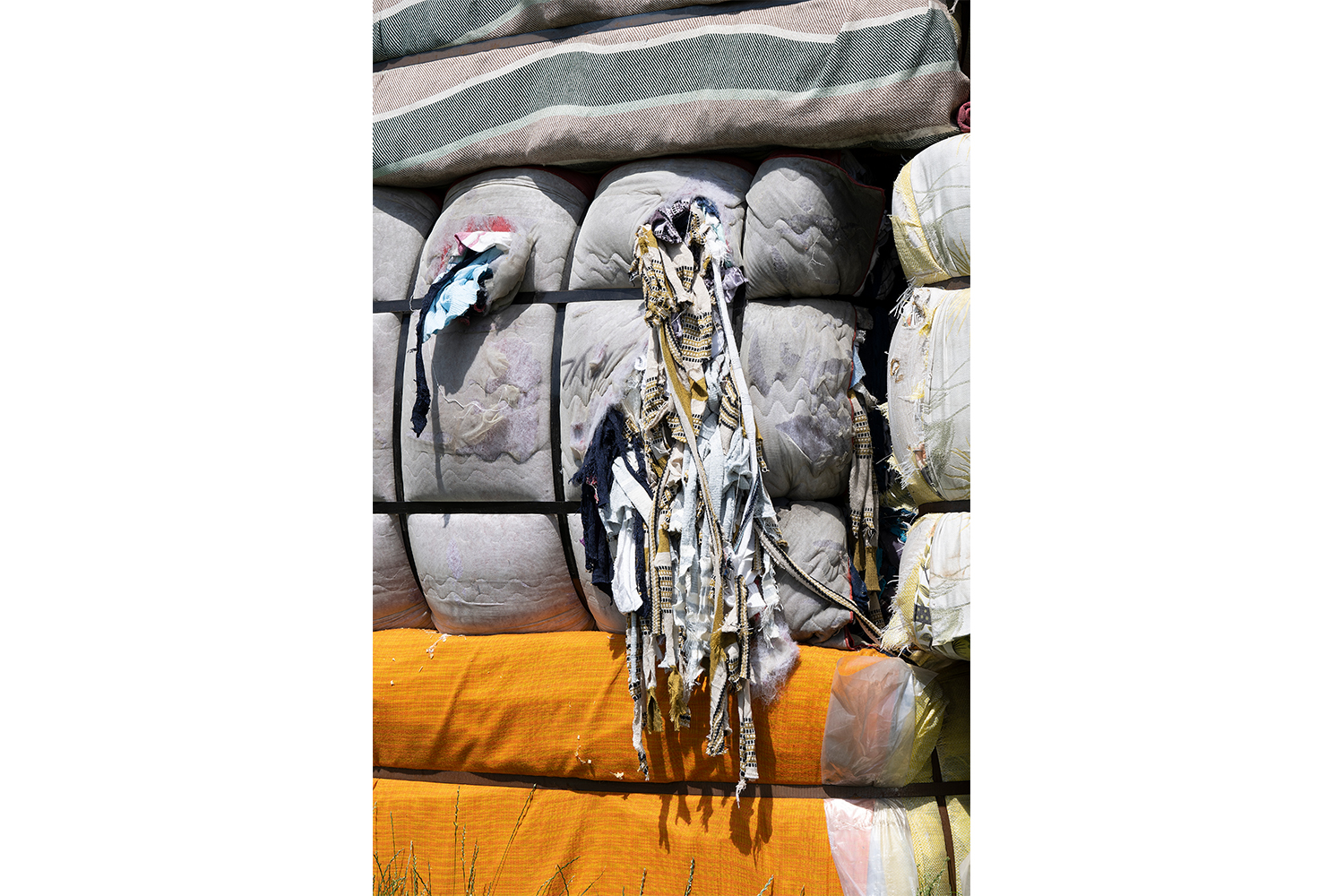

The title of this edition is “lumbung,” a name for a collective rice barn. Sharing, composting, and harvesting are ideologies that run through many aspects of the exhibition. “Harvest” is a word used throughout the exhibition’s many outputs, from Cem A.’s (aka the artist behind the Instagram account @freeze_magazine and the assistant curator of Documenta 15) smaller situated memes to some of the larger installations and projects like Erick Beltrán’s Lumbung Press, which situates a publication-printing service at the center of the quinquennial. Ethics are favored over spectacle and aesthetics. The ruangrupa collective have been transparent about their curatorial vision, stating in the Documenta 15 handbook: “Art is rooted in life. Instead of commissioning new artworks for Documenta 15, we wanted to show the processes that give rise to them.” So, one question arises: Is this something the invited contributions embody or convey? What are these processes? Are we bearing witness to them in the form of the emerging political landscape of Documenta 15 itself? The answer is complicated.

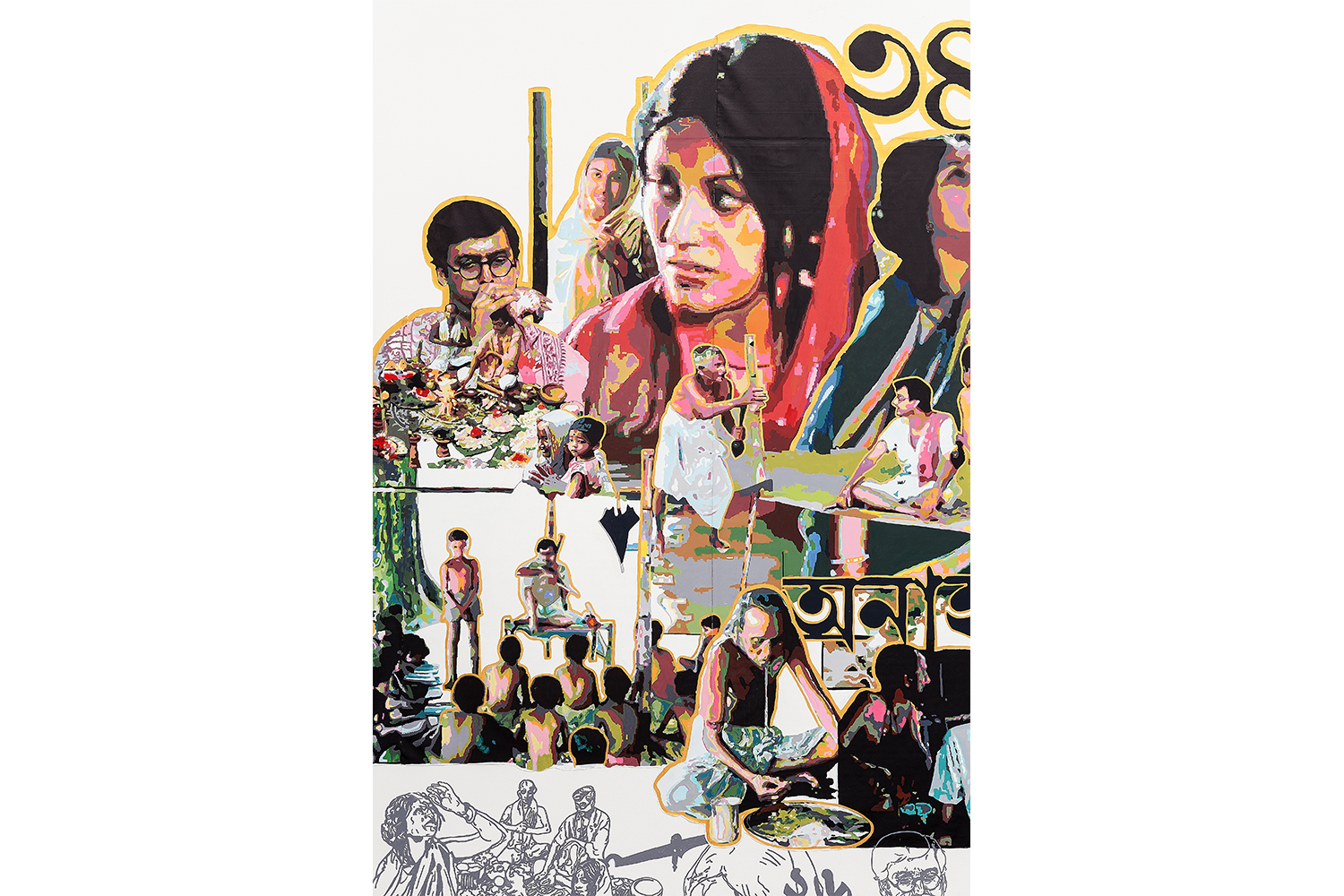

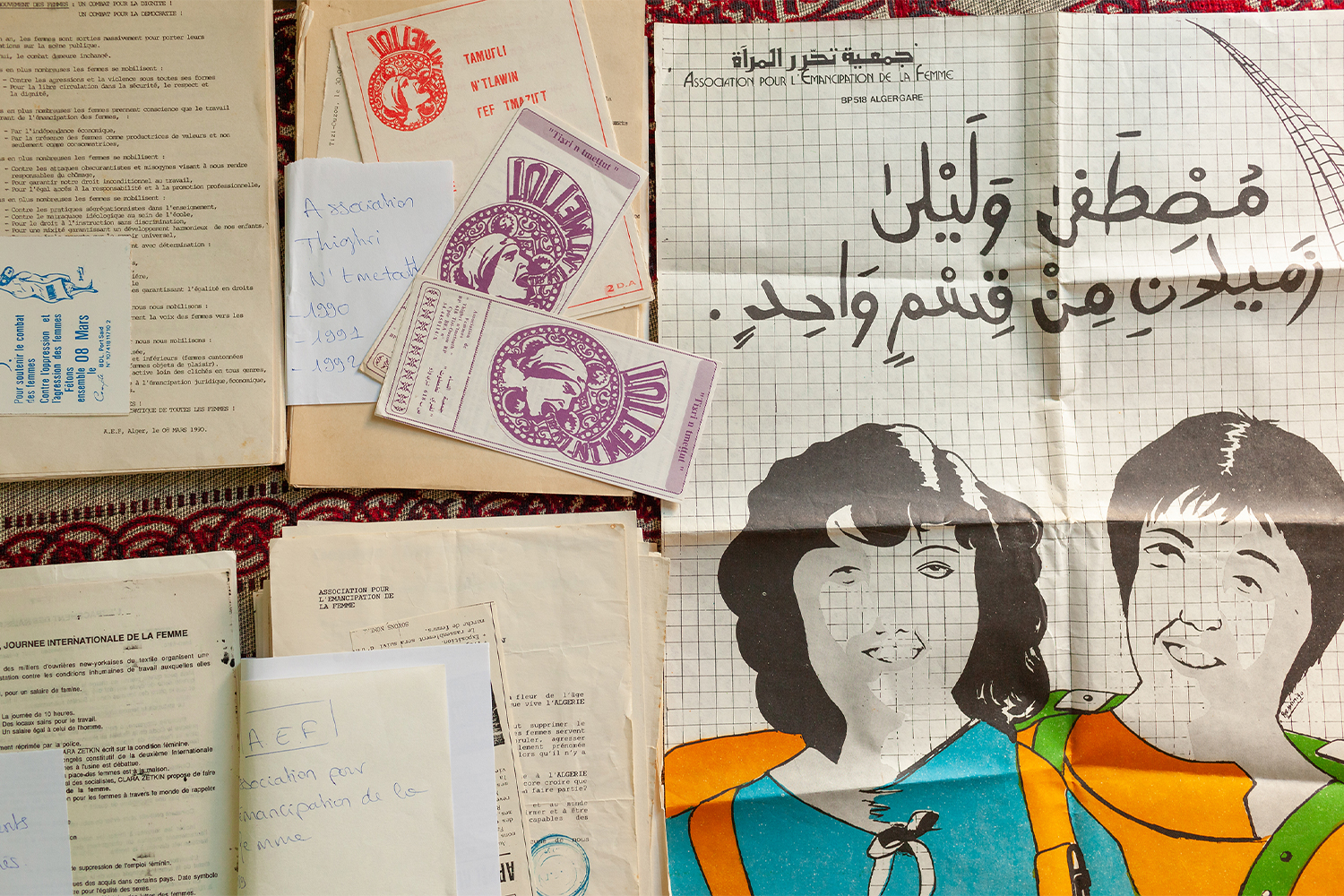

There is a huge disparity when it comes to the sophistication of exhibition-making across the quinquennial. On the one hand there are installations like that of Archives des luttes de femmes en Algérie. The group was founded by anthropologist and researcher Awel Haouati, later joined by researcher Saadia Gacem and photographer and archivist Lydia Saïdi after the 2019 “Hirak” popular uprising in Algeria. Installed at the Fridericianum venue, the installation comprehensively attempts to reconstitute a history of women-led activism and movements through a selection of archival documents linking the recent past to historical events in Algeria and the wider Algerian diaspora. Visitors are invited to read or leaf through a huge repository of reproductions of different materials from this period, including posters, photographs, and films. It is a contribution that could merit a day-long visit in and of itself. Other rough-and-ready contributions are more interactive, abandoning museological tendencies. The mediation of the exhibition seems inconsistent and seemingly less than inclusive. Early on during my visit I asked the information desk about the “Fanon Fried Chicken” neon sign outside the main information hub. Accompanied by the tagline “fast food for the wretched of the earth,” the piece was clearly a reference to the theorist Frantz Fanon. I was met by blank stares from the information staff who told me the sign was not part of Documenta 15, only later to discover it was indeed the work of Shy Radicals artist Hamja Ahsan.

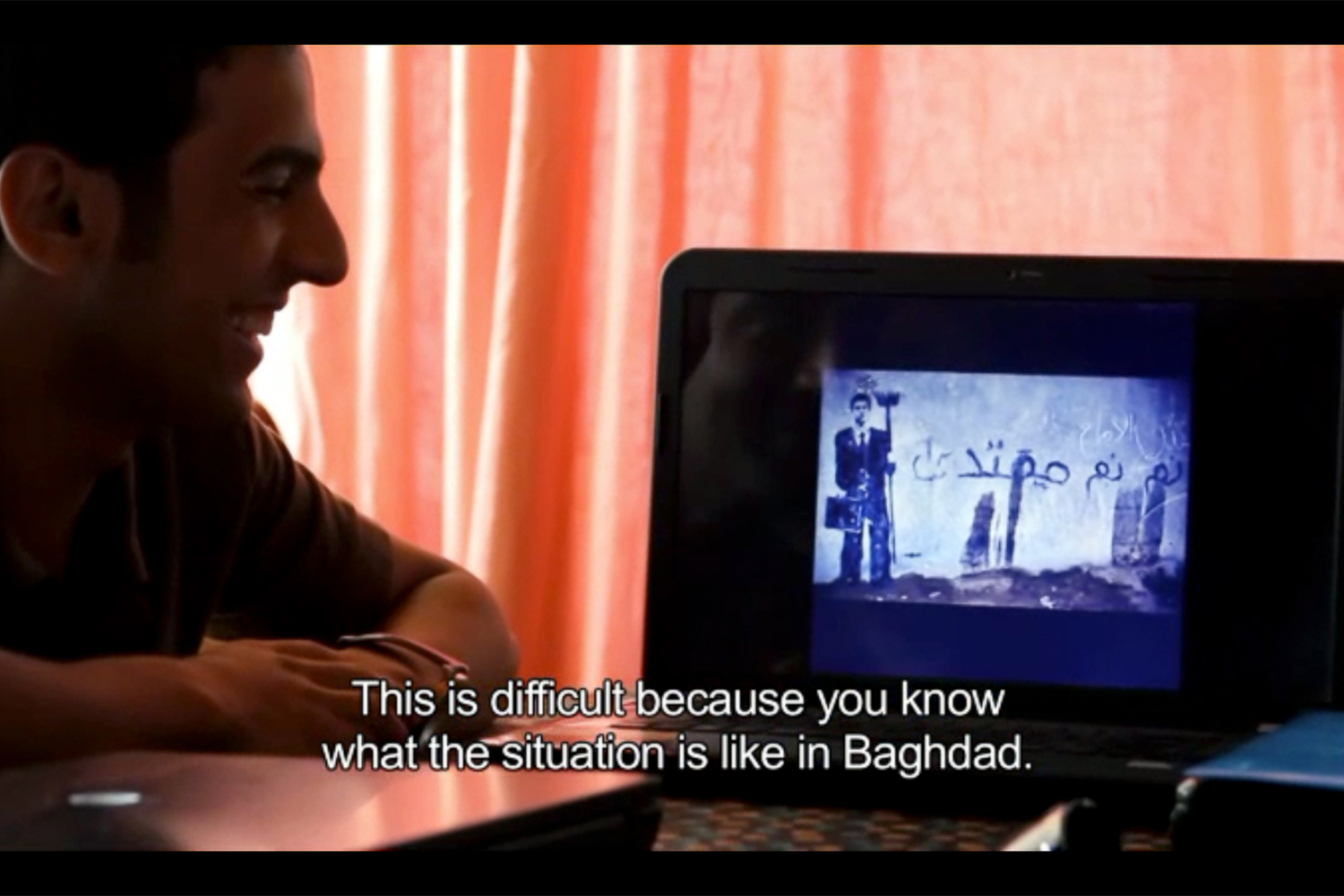

One contribution that undeniably embodies the curatorial vision of ruangrupa is Sada [regroup]. Sada, meaning “echo” in Arabic, was conceived as Sada for Iraqi Art by Rijin Sahakian (Baghdad). Sahakian set up Sada, which ran from 2011 to 2015, to support Baghdad-based artists who operated within the context of an obliterated contemporary art infrastructure in Iraq after years of war and continual political insecurity. For Documenta 15, Sahakian invited former participants of Sada to produce new video works reflecting on their practice and where they are today. Many of the included works show Iraqi artists struggling to learn art as students, but also struggling to exhibit their work within an oppressive system that determines what gets to be seen while perpetuating an ever-present threat of violence.

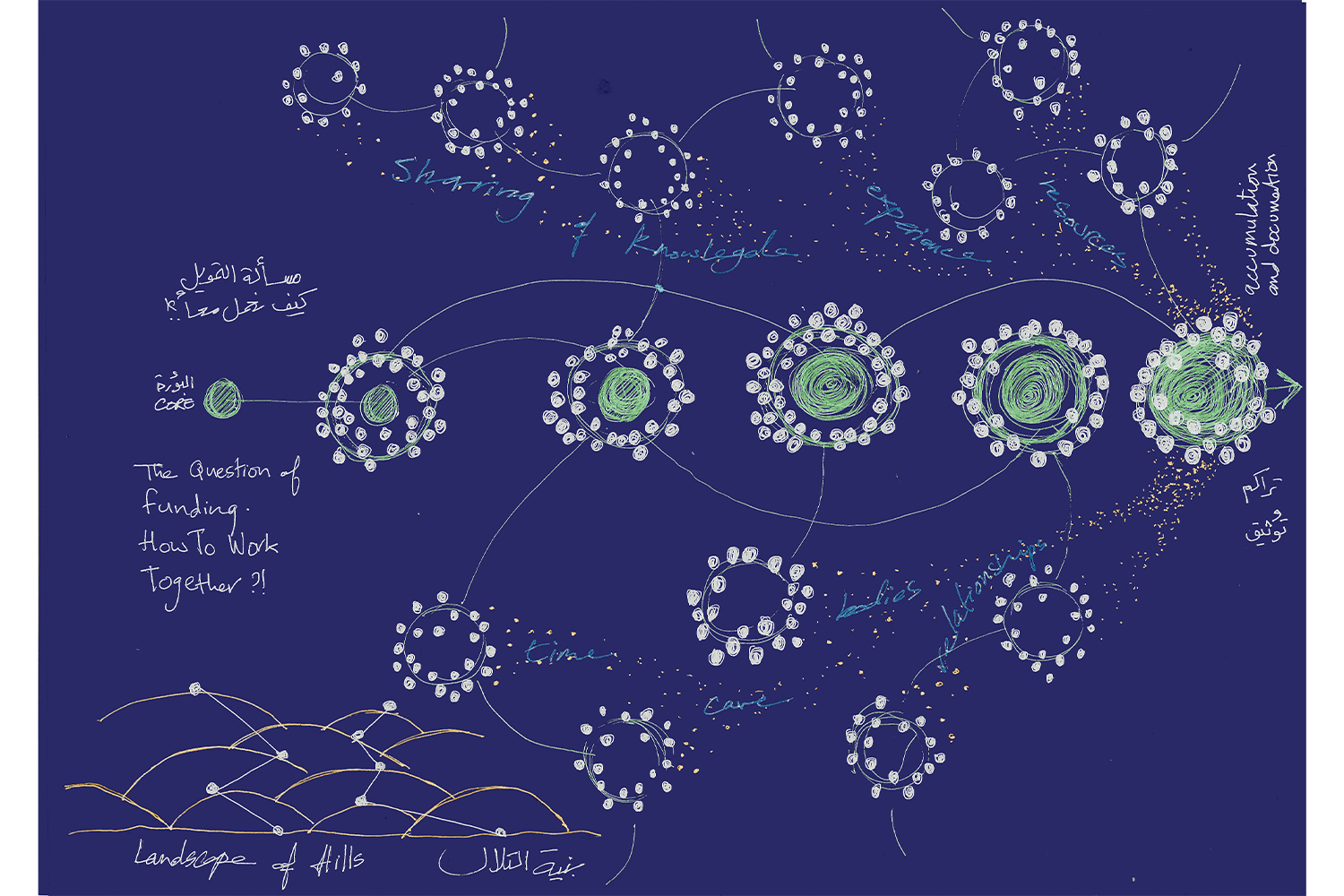

There are moments of humor. Football Kommando (2022) is a film from Wakaliga Uganda, an almost no-budget studio based outside of Kampala founded by Nabwana I.G.G. As well as being a movie studio, Wakaliga Uganda is a community project that keeps many teenagers from engaging in anti-social behavior through activities such as filmmaking. Visitors walk by numerous handmade posters of films produced by the studio, then enter a bean bag–filled theater showing a film about a German footballer teaming up with a Ugandan mother to rescue her kidnapped child. The film is completely engrossing and enthralling. Documentation outside of the theater space includes behind-the-scenes photographs. This work confidentially does the job of showing the process of collective production within a community without leaning on some of the commonly overused tropes (in particular mind- map diagrams) seen throughout the rest of the exhibition. The work is inclusive without needing to state as much; the work does the work.

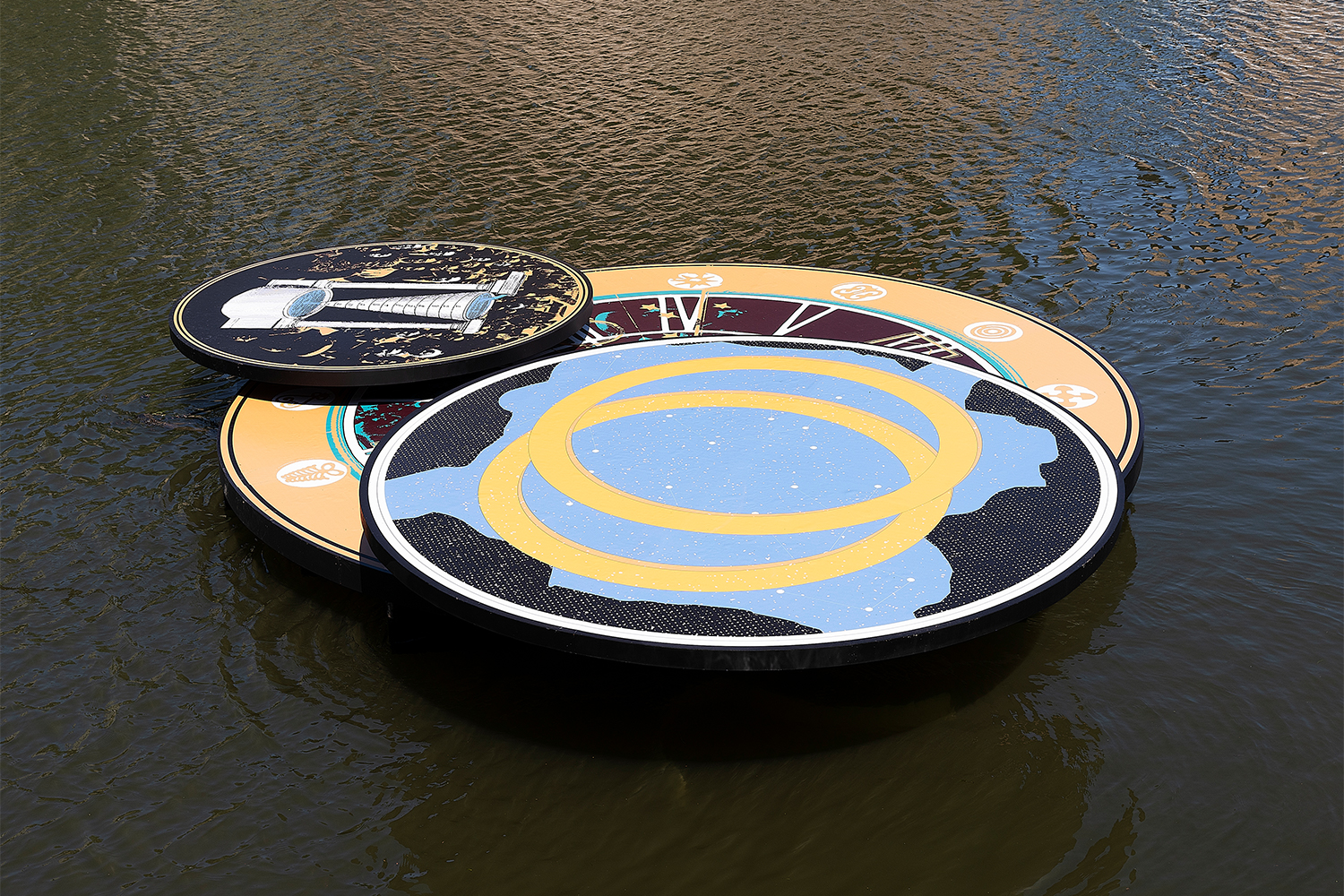

The Question of Funding co-curated an exhibition with Gazan artist collective Eltiqa, one of the oldest running collectives from Palestine. The contribution outlines ways in which economies entangle with forms of solidarity. The Question of Funding’s project cumulated unexpectedly with an invitation for Palestinians to use Dayra. net, a blockchain service described as “a medium for circulating communal economic value.” It is one of the very few references to blockchain in the exhibition, and one of the first I’ve seen used critically in a major exhibition this year.

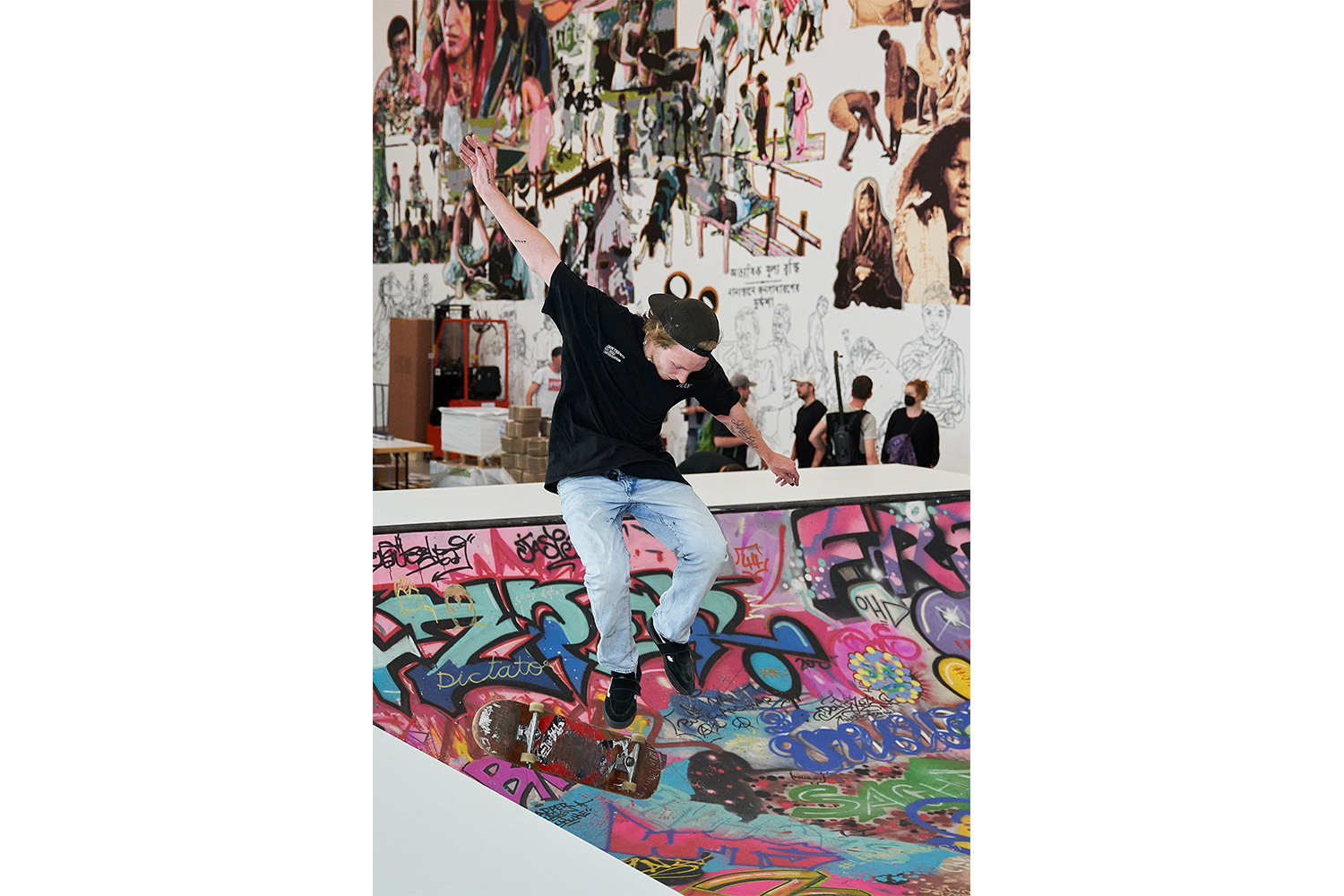

The works across Documenta feel like functioning social spaces. People are sleeping in the installations, chatting, debating, eating together, and even skating in the case of Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture, who erected a skate ramp at the center of Documenta Halle in collaboration with a local skate park, which will be open for skaters to use for the duration of the exhibition. Documenta 15 is “documenting” through a collective response to organize within the context of the strategic decline and disintegration of the notion of a welfare state globally. The exhibitions feel like community centers. Many (if not all) of these collectives were birthed out of an absolute necessity stemming from contexts of oppression, conflict, and gross inequality, in places where community spaces simply did not exist.

It is, however, the scale of this ambitious edition that perhaps lacks critical responsibility. Does Documenta really need to be this big? Was it necessary to invite so many artists? Often, you will hear visitors and critics alike state, “It is too big to see everything.” Did the curators manage to see all the exhibitions before it opened? What are the consequences and implications of this delegated curation?

On June 19, a 2002 work called People’s Justice, a cardboard mural made by the Indonesian collective Taring Padi, was removed from the show by the artists due to its anti-Semitic content. The work in question was part of a larger banner, depicting “a caricature of a Jew with sidelocks, a cigar, and SS symbols on his hat,” originally reported on by the German art publication Monopol. Accusations of anti-Semitism have engulfed Documenta 15 since January, due in large part to the anti-Zionist stance of several exhibiting artists and collectives. At the time of writing, there is an examination committee being brought together to comb through the exhibition, not looking for racist content but only what they deem to be anti-Semitic materials. The German government deems the support of the BDS movement as anti-Semitic. There have been protests over the removal of the work and what many contributors view as an attempt to censor. It is a reality that sits at odds with the initial premise of Documenta in 1955.

Acknowledging that the image is anti-Semitic is correct. However, it is an acknowledgment that also must come with a careful consideration and explication of the complexities that the work brings to question. Arguably this is something that the organization has failed to do. Eyal Weizman (Forensic Architecture) gave an excellent critique of the situation on the second day of the Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art’s conference titled “Imperial Ecologies” (which can be viewed on the Berlin Biennale’s YouTube page), articulating that much of the problem stems around epistemic failure — “the inability to undertake political analysis within activism.” He points out that now the problem lies with a validation of the claims and attacks that preceded the removal of piece. The organization of Documenta have failed to deal responsibly with the fallout of many controversaries, and the implications could be as far-reaching as the systematic dismantling of Documenta as it has come to be known. At the time of this writing, the New Delhi–based gallery and performance space Party Office has withdrawn their live program and wants Documenta to offer a public apology after artists reported incidents of racism and transphobic harassment in Kassel. Hito Steyerl has also just withdrawn her confidence in the organization.

Perhaps Documenta 15 hasn’t really started yet. It is feasible that there will be further withdrawals, which could result in the exhibition closing completely by the time that this piece is published. Surely this will become the catalyst for some sort of organized solidarity and response that finds a way to argue for the complexity of the situation and perhaps gives birth to a new collective that argues on its own terms and places analysis at the center of its activism. Perhaps every act of decolonization must reach a point where familiar structures must be totally dismantled and rebuilt.