Every night during the summer of 1993, artificial fireflies automatically lit up the garden at the Villa Arson, Nice. But nobody could see them; they only turned on when the museum was closed. This work by Philippe Parreno referenced the disappearance of the fireflies from Europe some thirty years before.1 Lightning bugs fascinate Parreno. He marvels at their uncanny ability to communicate and attract each other through light: “The firefly produces light intermittently. A flickering desire.”2 For him, they represent the rhythmic pulsing of the automaton, a figure that has become central to his work. Automata appear everywhere in his shows. They take the form of ghosts, puppets, aliens, impersonators, ventriloquists, robots, monsters, marquees, soundscapes, player pianos, automatic blinds, automated special effects, flashing lights, and especially the technology of film. Parreno believes that every form, image, or idea is part of a bigger dynamic structure, a chain of events. And, this chain relates directly to automation:

How do you chain one idea, chain one picture with another? At the beginning, I thought about that a lot: la chaîne. How do you link one thing to another? And I thought: there’s something automatic at work. That, in a way, is what became that nonhuman thing — something that operates without me. So you have to invent something that then operates automatically. An automaton.3

Since the beginning of his career, Parreno has sought to set up an interchange between people and things in a particular context. In art, this encounter takes the form of an exhibition. According to him, subjects and objects do not have fixed, predetermined identities. Both exist in a heterogeneous network of actors composed of humans and nonhumans taking on constantly shifting roles as either “quasi-subjects” or “quasi-objects.”4 In other words, relations precede the terms of the relationship. A football cannot exist without the game. Parreno, therefore, considers the exhibition as primary, insisting “there is no object without its exhibition.” He sees his exhibitions as open-ended scenarios that create the unexpected and new.

Parreno insists that an exhibition is a temporal relationship just as much as a spatial relationship. For him, the question becomes: When does an artwork appear or disappear? The visibility of a work depends on many factors such as museum hours or the length of an exhibition. Invisible to the public, the Villa Arson fireflies only flickered after hours. The visibility of an artwork also depends on how long the spectator decides to spend in front of it. But how do we know how long to look at an artwork? We know how long to watch a film because a timecode, a synchronization method used in film editing, predetermines its duration. Cinema has a natural relationship to time. For this reason, Parreno set out to mount his exhibitions like you would edit a film.5 Since then, instead of considering his artworks a collection of inert objects, he scripts their visibility in time using automation technology. His exhibitions take the form of a chain of programmed events, a network of “quasi-subjects” and “quasi-objects” where the works “appear and disappear, act upon and, in turn, are acted upon.”6 To be clear, these are not deterministic rational systems. He doesn’t use automation as a tool to assert artistic control. Playing the role of a kind of occult technician, Parreno enchants his technology, and his shows grow into productive, stochastic, semi-living automata.7 They become desiring machines.

ALIEN AFFECTS

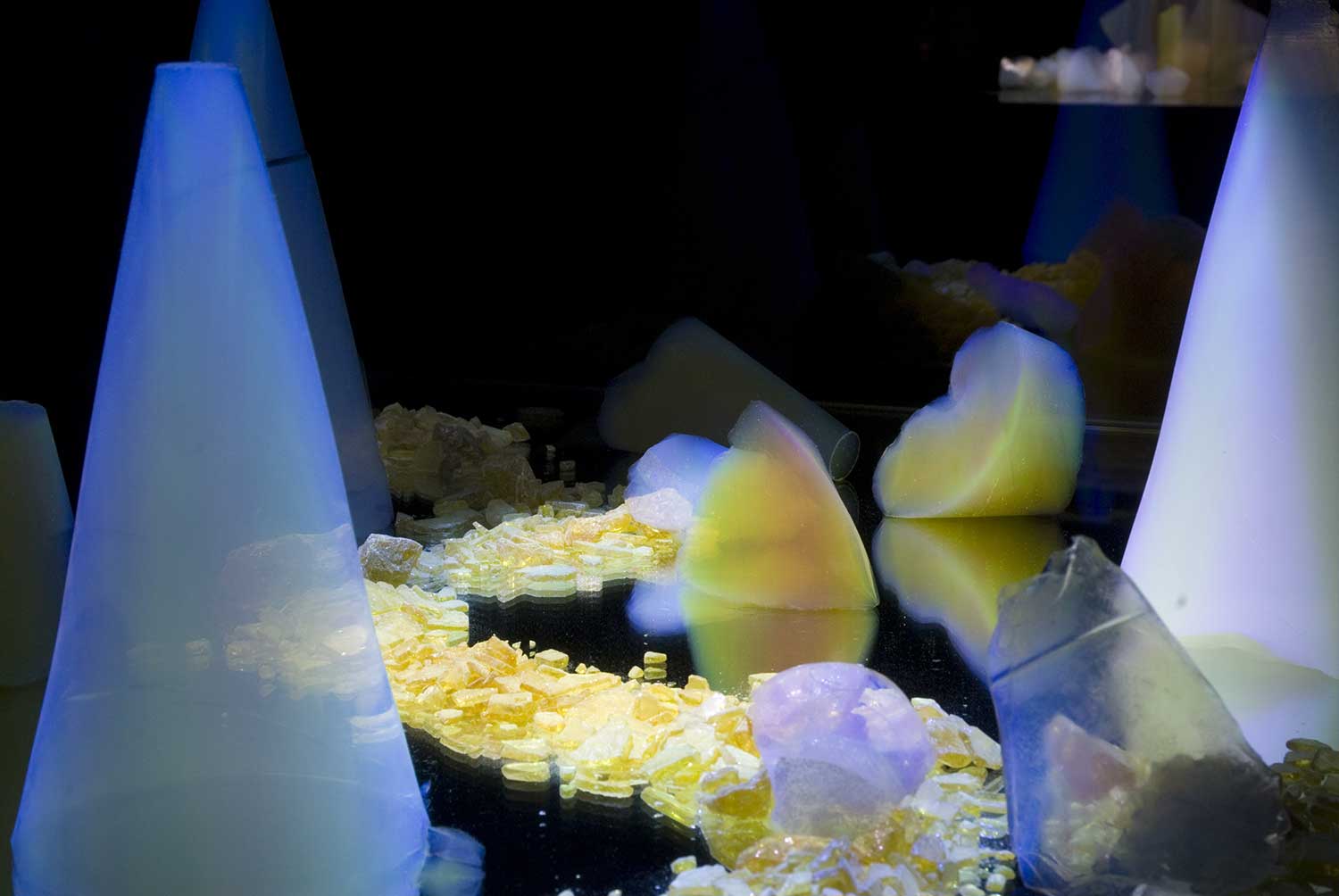

Parreno’s first programmed exhibition centered around the alien perspective of a cuttlefish. To plan this 2002 show titled “Alien Seasons” at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, he collaborated with computer scientist Jaron Lanier, one of the inventors of virtual reality. Both Parreno and Lanier share an obsession with cuttlefish, which they believe are “the closest thing we have to aliens”8 on Earth. Just as with fireflies, Parreno has become fascinated by the nonhuman affective way in which cephalopods communicate. The cuttlefish possesses a unique image-generating lobe that allows it to generate images and colors on the surface of its body directly from its imagination. The language of the cuttlefish, Parreno and Lanier agree, has extremely important implications. It suggests the possibility of developing a more direct, pre-conceptual form of expression than human symbolic language.

To program this exhibition, Parreno set up a network around his film Alien Seasons (2002) with a show controller, a type of automation technology that uses a timecode to link together the various multimedia elements of an attraction. The film comprises six sequences of a giant cuttlefish that changes colors in response to its environment. Whenever a new sequence of this film began, the show controller triggered various effects at different times and places in the museum. Automatic blinds came down, and colored beams of light translated the novel Le Mont Analogue into Morse code; lights turned on, allowing 4 minutes and 33 seconds of silence to look at Robert Rauschenberg’s White Painting; lights switched off and the film El Sueño de una cosa was projected onto the painting. In this way, the images of the cuttlefish in the fictive space of the film orchestrated the experience of the actual space of the exhibit.

A PARANOIAC LOGIC

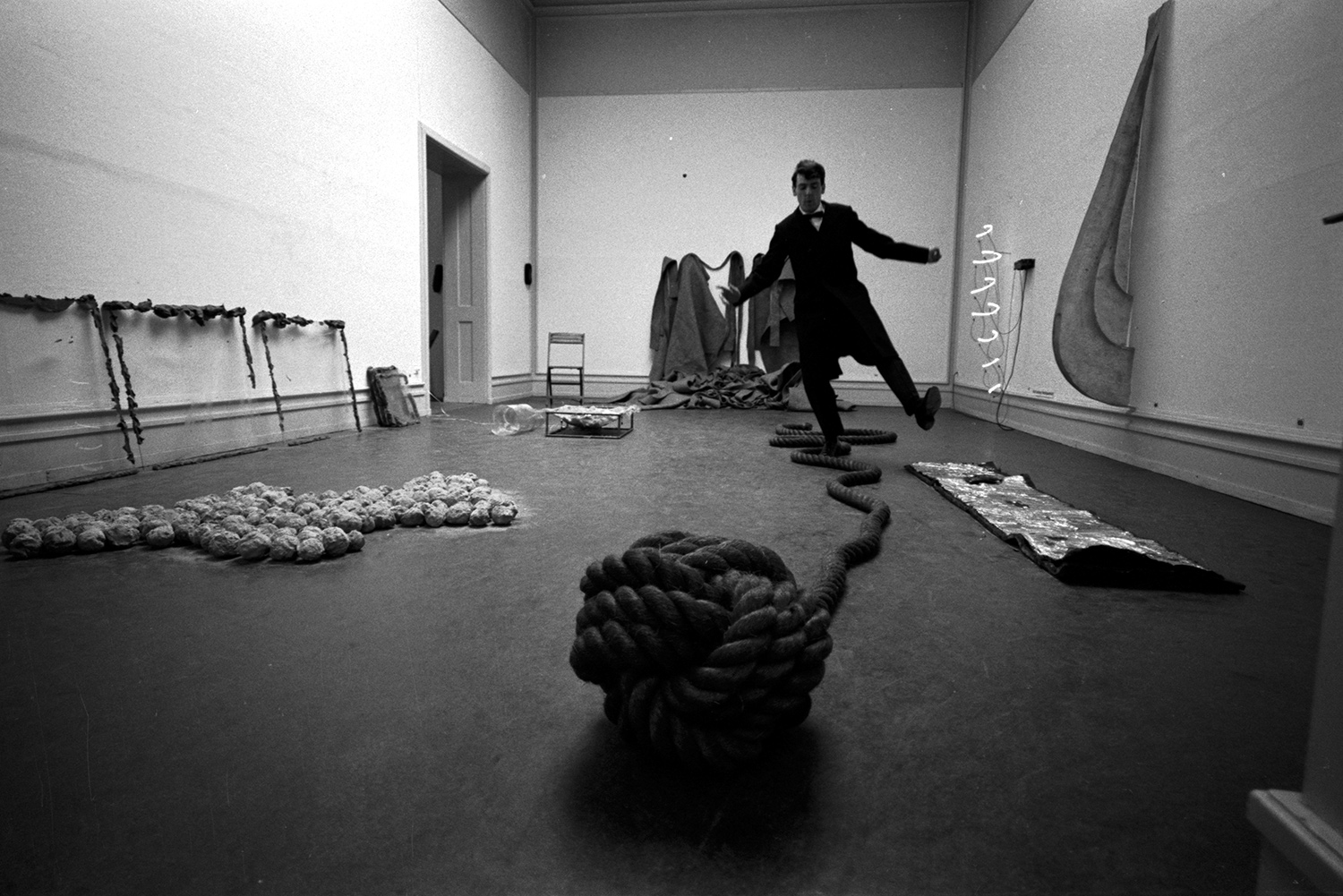

Since “Alien Seasons’’ Parreno has experimented with increasingly complex ways of organizing his exhibitions. In 2013, for “Anywhere, Anywhere Out of the World” at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, he used advanced computer technology to choreograph visual and aural effects throughout all 22,000 square meters of the exhibition space.9 This show came alive to the musical composition of Igor Stravinsky’s ballet Petruška. Parreno worked with sound designer Nicolas Becker to encrypt the score and break it down into many parts, each part animating an event in the show. Petruška tells the story of a puppet that comes to life, gets killed by another puppet, and then returns as a ghost. In “Anywhere, Anywhere Out of the World,” four Disklavier pianos (high-tech player pianos) dispersed throughout the space played the score that orchestrated every effect in the show. Virtuoso pianist Mikhail Rudy prerecorded the music, but the pianos appeared as if played by ghosts. In fact, everything in the show seemed haunted. A wall turned around a dance floor where the footsteps of invisible dancers were heard. A dark passageway suddenly lit up with frenetically flickering marquees. Their bulbs played “Dance of the Nannies” from Petruška note by note, the frequency of their light corresponding to the frequency of sound. The fluorescent museum lights blinked agitatedly, each of the fifty-six wall sconces dancing to the beat of one of Petruška’s fifty-six episodes. A play of light, sound, and images guided the visitors throughout the labyrinthine space. Upon entering the show, the visitors saw TV Channel, a huge LED screen showing some of Parreno’s early videos. As the spectators came closer to the screen to watch the films, the image and sound began to fade like memories. From close-up, they realized that the screen was transparent, bringing into focus other sights and sounds to follow. Such tricks of the eye and constantly changing perspectives made it impossible to understand the show according to the common-sense coordinates of human reason. The show became a self-motivated machine that functioned according to a paranoiac logic, a complex polyrhythmic space scattered beyond any single focus of attention.

Opposed to the traditional retrospective format, Parreno considers his exhibitions rituals in which his previous works revisit him. He believes all his objects and characters, whether fictional or not, are real beings that exist without him. But, like ghosts, they lack finality, and they almost always return to tend to unfinished business. As Parreno has stated, they desire a fuller existence.10 These forever-incomplete artworks come back, but they never reappear exactly the same. With each new ritual in each new exhibition, the image takes on a new life.

THE BRAIN IN THE VAT

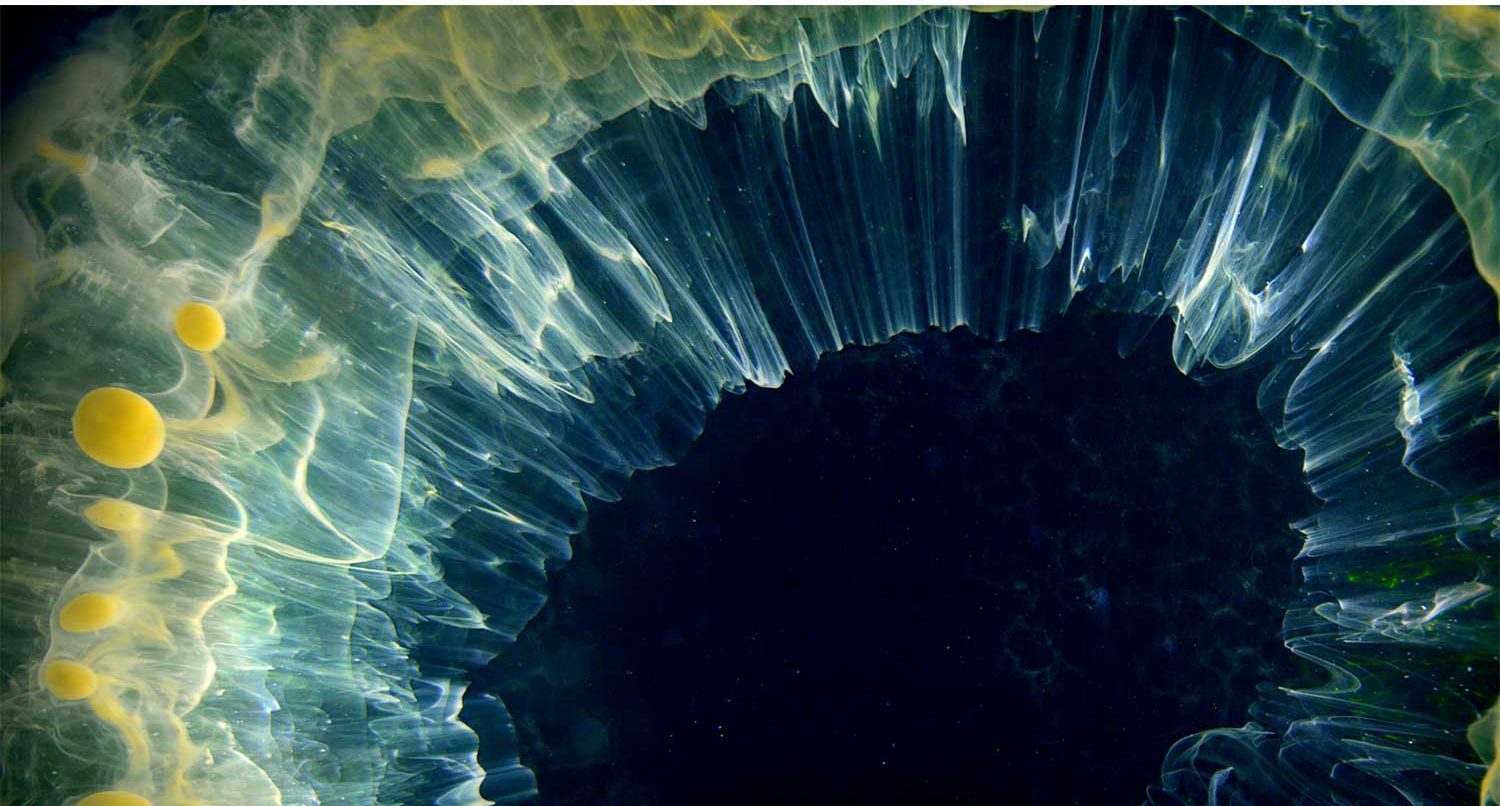

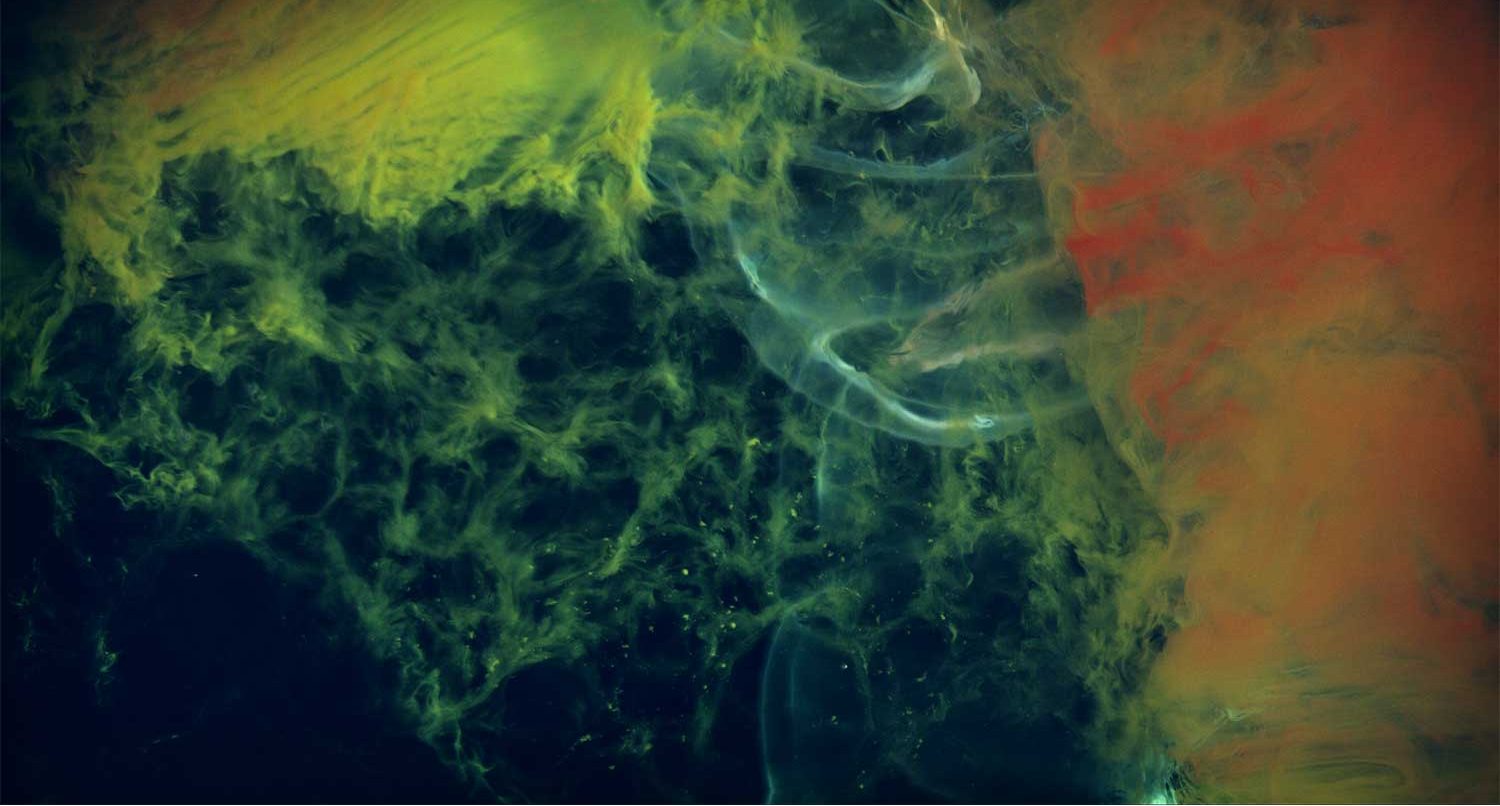

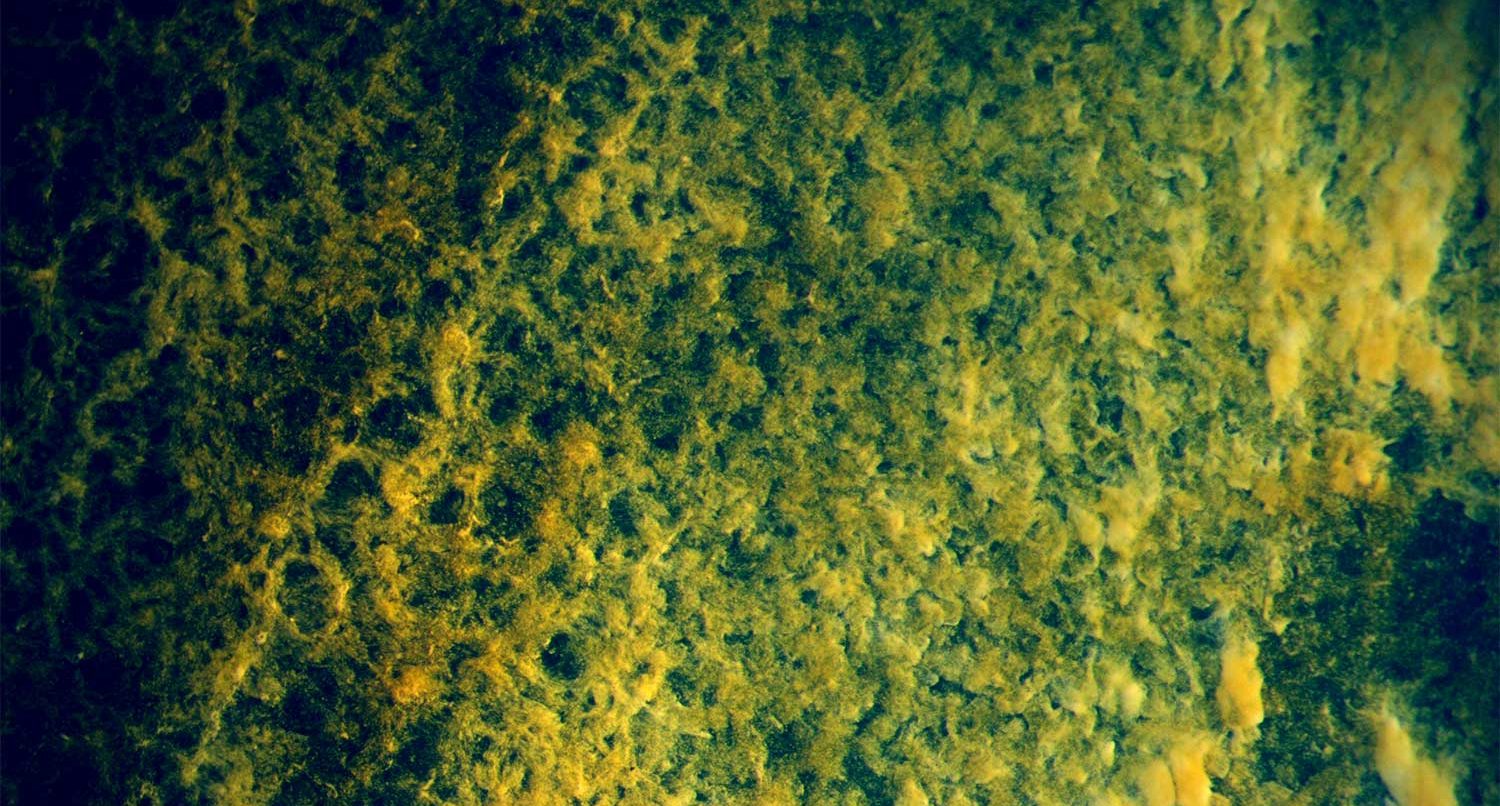

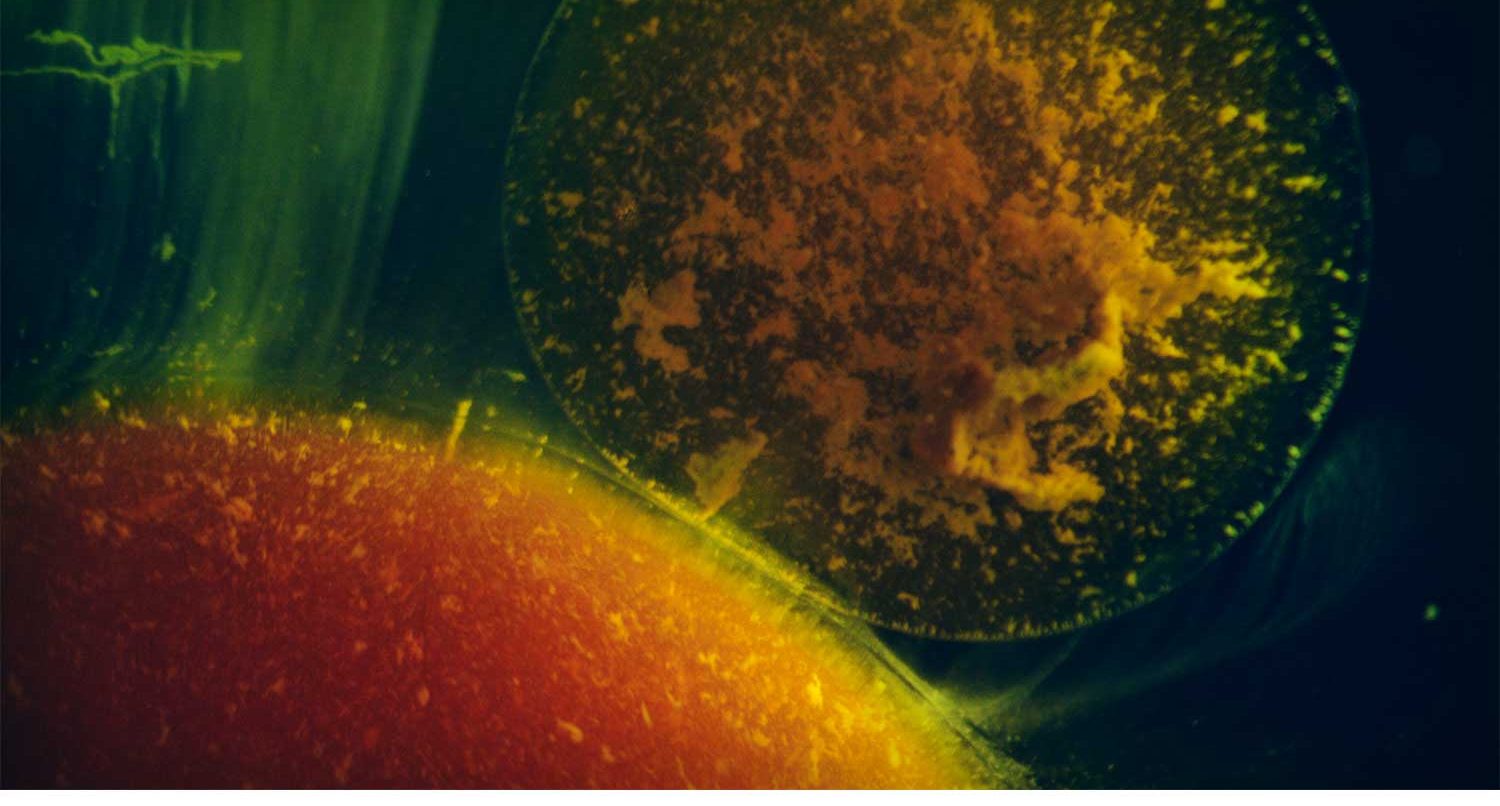

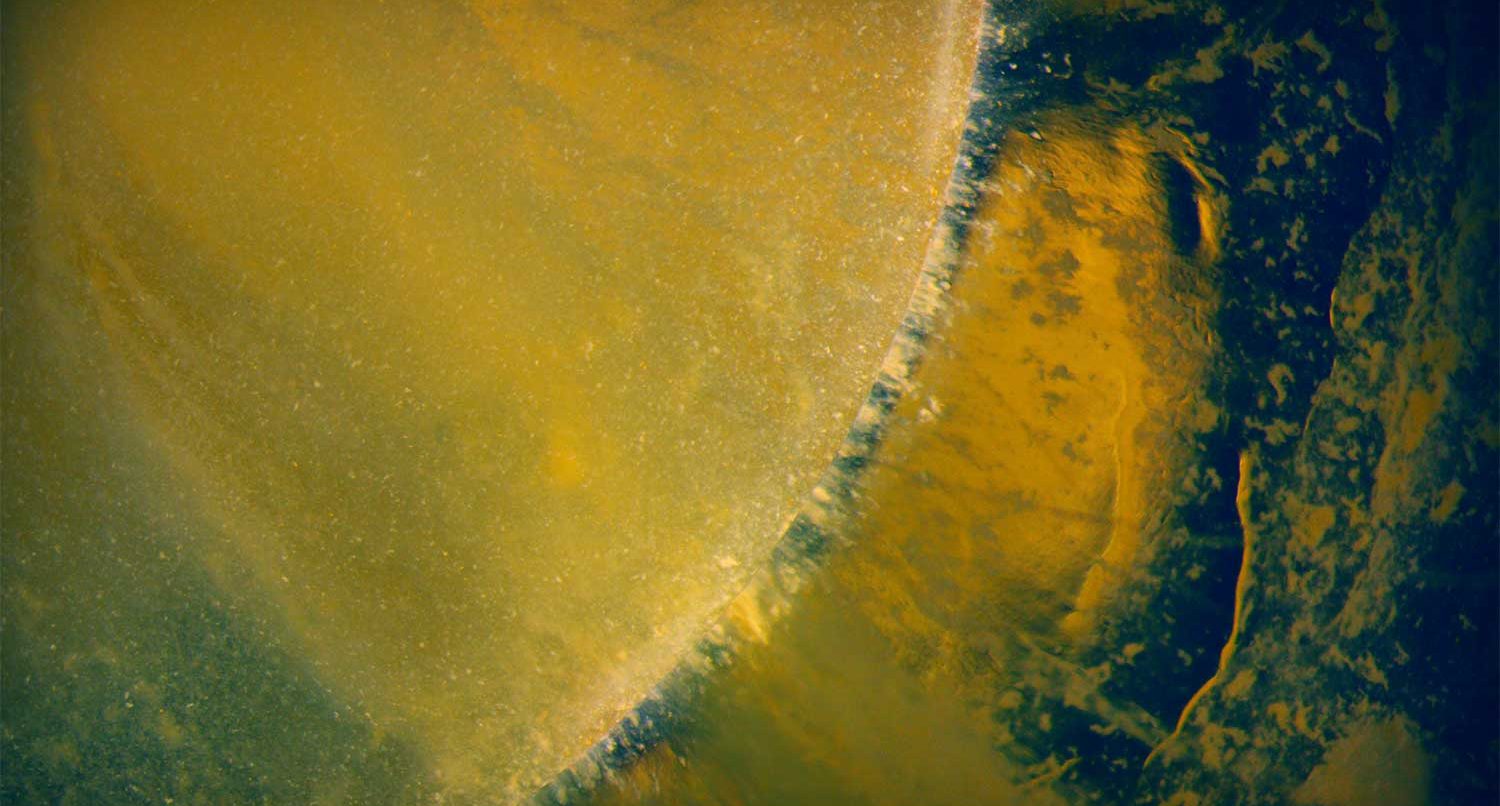

Recently, in a sci-fi-like scenario, Parreno has relinquished his artistic control to a growing community of sentient bacteria. For his 2016 show “IF THIS THEN ELSE” at Gladstone Gallery in New York, Parreno began using a bioreactor, a nonhuman collective intelligence, to run the dramaturgy of the show. The bioreactor consists of a beaker in which a colony of yeast multiply and mutate. Connected to computers that controlled the sequence of events, these unicellular microorganisms developed a memory, learned the changing rhythms of the exhibition, and evolved to anticipate future variations. For “ANYWHEN” at Tate Modern, the bioreactor interacted with a weather station collecting data on the roof of the building. Changes in light, temperature, and wind outdoors affected the yeast’s growth, which in turn determined the events in the show. As the microorganisms communicated with each other, with the computer software, and with the contingent events of the outside world, their neural circuitry set in motion an elaborate, nonperiodic, nonlinear mise-en-scène. They decided when to turn lights on and off, prompt screens to go up and down, play short films, and diffuse sound. Throughout the six-month run of the show, the bioreactor developed an increasingly complex choreography that changed by the day. The play of darkness and lightness corresponded to a nonhuman circadian cycle, disrupting the normal sequential order of things. This alien brain in a vat became the living control center, the puppet master of the exhibition. Functioning on a molecular timescale imperceptible to humans, the microorganisms evoked the possibility of alternative, less anthropocentric realities. These bacteria provide a convincing argument for panpsychism, the belief that everything in the universe, whether living or dead, possesses a degree of consciousness. What was once considered fiction is now taken seriously by science.

FLASH FORWARD: THE REAPPEARANCE OF THE FIREFLIES

In 2014, the fireflies returned. For Parreno’s animation With a Rhythmic Instinction to be Able to Travel Beyond Existing Forces of Life,11 hundreds of the artist’s drawings of lightning bugs flashed on an LED screen then faded away, their lifespan governed by a cellular automaton. This cellular automaton, a computer program entitled “The Game of Life,” consists of an infinite grid of “cells” that have two possible states: alive or dead. The cells change states over time according to the states of their neighboring cells. In Parreno’s animation, chance and the rules of the game determine the sequence of the drawings and the lifespan of each group of fireflies, which can stay on the screen from a few minutes to several hours. Whenever a sequence dies, a drawing of a firefly freezes on the screen and then disappears. After each death, a unique sequence of drawings animates the screen, and life begins anew. Scientists studying artificial life, a field that develops computer models to simulate living systems, have used cellular automata to show the surprising ways in which complex, lifelike behavior can emerge from simple rules. This field does not study “life as we know it” but rather “life as it could be.” Similarly, Parreno’s cellular automaton endlessly generates different combinations, speculating on an unpredictable future open to infinite variations. As the work develops increasingly dynamic patterns, it shows the potential for new forms to self-organize out of silicon-based material. Many fireflies disappear, but for Parreno, their death marks an important break in time. The future necessitates a rupture with what has lived in both the present and the past. New forms do not emerge in a continuous process. Lights must flash on and flash off.