One could easily describe Deborah-Joyce Holman as an “inter-” or “multidisciplinary artist,” though the term merely suggests someone who works across different media — it does not capture the expressive and intentional intricacies of Holman’s career so far, which began with exhibiting conceptual sculpture and installation in tandem with their studies at HEAD Genève (2015–18); then developed through curating the work of young artists at their project space 1.1, Basel (2015–20), as well as at two editions of Les Urbaines festival in Lausanne (2018 and 2019); continued in their role as associate director and curator at Auto Italia, London (2020–22); and most recently turned toward moving-image. Their newest work, Moment 2 (2022), an ambitious, nine-hour film shot in one take and starring artist Rebecca Bellantoni, premiered earlier this year at schwarzescafé, Luma Westbau, Zurich. As has been the consistent, steadily emergent theme of Holman’s practice thus far, the work is motivated by questions of subjecthood and identity, and the reciprocal nature of its expression and manifestation, be this through gesture or practiced ritual. In the following conversation with Cédric Fauq, Holman ruminates on the aforementioned themes within the context of language — its confusion and illegibility — endorsing total refusal as an adequate representational proxy.

Cédric Fauq: This year was a big shift for you: you decided to leave your role at Auto Italia to focus on your practice as an artist. What was the incentive to make that decision? As a curator myself, I guess I’m interested in how you look at this experience now. I mean, you’ve always been an artist supporting other artists.

Deborah-Joyce Holman: I started my project space 1.1 in Basel in 2015, at the same moment as I started studying my BA in Visual Arts at HEAD Geneva. My curatorial practice really grew out of that, quite spontaneously so — 1.1 was founded spontaneously, I never had the intention to run a space before that. It developed organically as I was motivated by being in exchange with artists, to work alongside them in production and exhibition- making as well as being in a position where I could contribute to the Swiss art landscape. In that sense, yes, as you said, I’ve worked as an artist supporting other artists. I worked at Auto Italia in London over the tricky years of 2020 until 2022, which has been wonderful.

I learned a lot, and again, it fed my interest in working collaboratively — within the team and with the artists, though of course our public activity was significantly limited because of the pandemic. Those years have brought lots of shifts with them — I guess for everyone. For me, one of those shifts was an increased urgency to facilitate the space to fully focus on my artistic practice. Looking at this experience now, I’m happy to have some curatorial and directorial experience. Especially with how I approach moving image, the elements of curatorial work that I enjoy are continued: collaboration and exchange.

CF: We got to speak recently at LUMA Westbau about your recent exhibition there. I was so happy to discuss this great piece (Moment 2) with you, but maybe there are some questions that we didn’t talk about… a bit tougher… more difficult. I’ve been thinking a lot about the role I play in the consumption of Blackness as a mixed-race curator. I mean, you and I both try to refuse and complicate the way Blackness heavily hinges on representational strategies within the arts. I’m wondering if this is linked to a specific European/mixed-race position…

DJH: I think so, just as much as anyone’s positionality influences the way they see the world, the words they write, the work they produce. Maybe more interesting to me would be the question of “how” our positions become tangible in our work — in a way, to look at the world through relation. The push towards complicating and approaching with nuance, etc., also comes with heavy work that isn’t necessarily visible or isn’t even a part of “the piece” or “the exhibition.” I don’t want to shy away from these questions, as I’m interested in counter-stances and refusal, which are always already in relation with whatever it is countering. I’m invested in understanding how we can formulate refusal, how an otherwise can exist. Lately, I’ve been reflecting on that entanglement and whether it is itself a distraction from that “otherwise.” This is, for me, where positionality comes into it. If we’re trying to complicate, it takes the effort to also be specific, and as such, of course our specific socio-cultural context has to be taken into account. What are your thoughts on this at the moment? And how does it influence your curatorial practice?

CF: I guess the more I “progress” in my thinking, the less I feel the need to label Blackness and queerness. I work through Black and queer methodologies because they’ve infused my thinking around exhibition- making and the world. I’m not saying this is a given; it’s just part of my artillery, which I’m continually working to sharpen. I guess I feel less pressure to be “recognizable,” and I like to come across as reassuring and easy — it gives more space to take risks actually. The possibility to conceive exhibitions like Trojan horses is something I learnt from Sam Thorne, who I worked with at Nottingham Contemporary (who himself learnt this from Alex Farquharson who probably himself learnt that from someone else… maybe Kodwo Eshun!). Would you say that Moment 2 operates like a Trojan horse somehow? I’m very specifically asking this question in relation to the share of violence the work responds to, and the seeming softness and comfiness the video first conveys.

DJH: Definitely! Both Moment and Moment 2 are structured by the repeated recital of selected excerpts from Shirley Clarke’s 1967 film Portrait of Jason. Moment featured the amazing artists and performers Rebecca Bellantoni and Imani Mason Jordan, and was composed of a two-channel screening, which I presented at the ICA earlier this year, where each performance took place on a separate screen. There are moments where their speech falls together, some where it falls apart, and then some, though we rehearsed separately and it was filmed individually, where it’s almost as if they were dialoguing. It becomes a play between the two performances, where the overlapping speech becomes like waves crashing into each other, flowing with each other, making rhythm and pauses. Moment 2 then pulls the words more into focus by comprising only one single channel with Rebecca Bellantoni, who again performs over and over and over again words uttered by Jason Holliday. What you call Trojan horse I have been thinking about through notions and subtle acts of refusal and opacity. In their excessive repetition, the words become hollow containers themselves, as their meaning shifts and changes or sheds away completely as a result of the repetition. And especially in Moment 2, where there is nothing else, we have to sit and hear these words over and over, and there’s really no distraction over the course of its nine-hour duration. That’s maybe also where a shift happens from the lulling and comforting repetition to the no-distraction focus on the words, and where a sort of implicit violence becomes more apparent.

I listen to a lot of experimental music, electronic and instrumental. One thing that I’m always drawn to there, too, is the loop, especially fake loops or those that are imperfect because the instrumentalist repeats a section over and over again rather than playing one loop and automating the repetition of it. The imperfections that come out of that and the slight frictions between instruments creates this tension that holds so much more information than the notes themselves. There’s an overlap maybe also with my interest in asemic writing, where semiotics are abandoned to get closer to the opaque, the excess, the irregular vibrations that carry information more of quality and relation rather than what’s speakable. The loops in Moment and Moment 2 are essential to me for that reason. They are intended to function in a similar way, thinking here also on the power and politic of the voice, of speech. What happens when these specific words of Jason are spoken aloud over and over, those instances where he proclaims himself as a slippery being, those instances where he makes explicit his awareness of the imbalanced, even extractive, dynamic between him and Shirley?

In relation to jazz, as well as with the original Portrait of Jason, there is a lot of this excess energy or excess information swirling around. Scholar Tavia Nyong’o writes about this in terms of crushed blacks and overexposed whites on the actual film strips in Afrofabulation: The Queer Drama of Black Life. Formally these are faulty areas, to which he ascribes the potential of agency and refusal. The way I’ve been thinking about repetition and recital departs from that point in shifting back from the “archival refusal” to the enactment of refusal.

CF: It might be interesting for readers to understand how you got to Moment 2, starting with Moment, which was screened at the ICA first. The process of remaking the work, rehearsing it again, is somehow where refusal is enacted too, right?

DJH: Moment mirrors the duration of Portrait of Jason, as it is also 107 mins long. For Moment 2 I extended it to be 540 minutes to correspond to the opening hours of schwarzescafé, Luma Westbau, so as to avoid the film looping and instead solely work with the imperfect loops, the repetitions I was speaking about before. I worked closely with Imani Mason Jordan and Rebecca Bellantoni. They’re both incredible artists, curators, performers, writers… and importantly, they both have complicated relationships with performing for the camera.

Taking Portrait of Jason as a starting point interested me, as it exemplifies so many problematic dynamics — one of which was the way Jason was choreographed and the mode in which the camera captured him. They filmed over the course of twelve hours through the night at Clarke’s suite at the Chelsea Hotel in New York. Through the course of those twelve hours, Jason gets more drunk and high and tired, I’m guessing as are the people behind the camera. Combined with the abrasive questions Clarke and her then-boyfriend Carl Lee ask, the film takes the approach of scratching away the surface of someone, peeling away at how Jason himself wants to present himself. There’s something really troubling, that speaks to maybe a wider dynamic of a huge appetite for trauma, or, specifically Black trauma, which turns trauma into a consumable, especially in images and video. The rehearsals were shaped by lots of conversations with Imani and Rebecca about the text excerpts, about Jason and about this film project and their role in it. I rehearsed with Imani and Rebecca individually, with a main focus on the recital of the text. The script, the decisions of which excerpts to use and the different configurations of them were informed by those rehearsals.

Imani has an extensive practice of performing poetry and spoken performances at large. They have an incredible register and way of moving through the set. They very much enact Jason’s words. It stands in contrast to Rebecca, whose voice gives such depth to each word without doing much else. They both performed very, very differently, which I love about the first version, because it creates this space between the two performances and two iterations of the same text. Moment 2 included more rehearsals again and discussions, as it’s quite a big ask to invite someone to perform for nine hours straight. There was something quite unsettling about doing it all over again. On the one hand, it is of course much more strenuous, but on the other hand, the long duration of the performance and of the film allows for more slipping away, as audiences would typically only see excerpts of the film. It changes the relationship to time as well, though both versions were one-takes and very much real time, but the knowledge that the film keeps playing for nine hours almost spills it over into a performance more so than a film, and hopefully creates some sort of friction with the audience in terms of how time is felt.

This went hand in hand with developing the image together with my friend and director of photography Jelena Luise, who I’ve been working with for both versions of Moment as well as my first video work, Unless (2020, in collaboration with Yara Dulac Gisler). In both projects there was a big negotiation around the role of the camera and its movement (or non-movement in Moment and Moment 2), which we thought about as a part of what’s going on in front of it and as such was part of the performance as opposed to a neutral bystander. The way we were thinking about the set was also as a performance in that moment that happened once. The set included the off-camera and the camera itself as just an element inside that set.

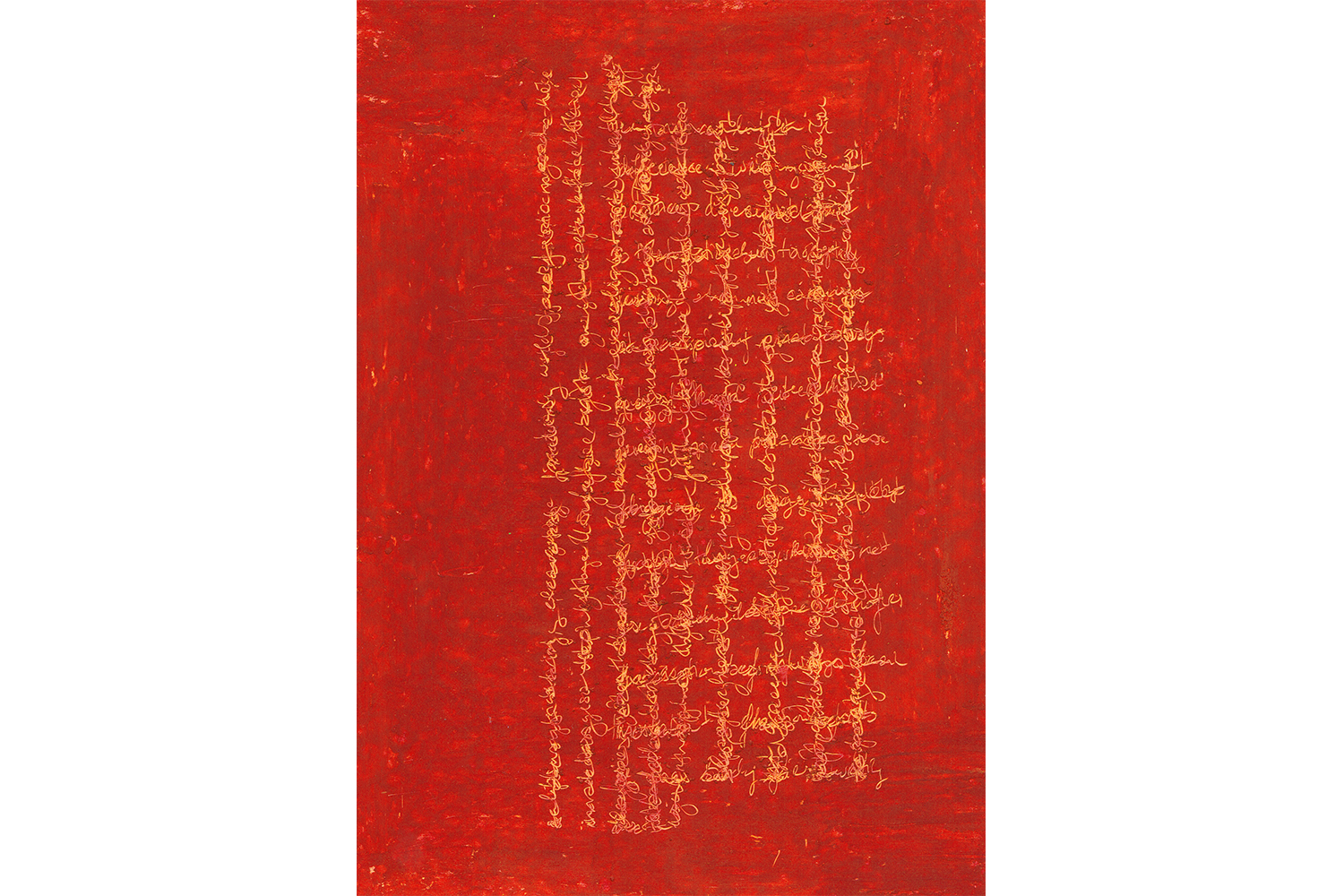

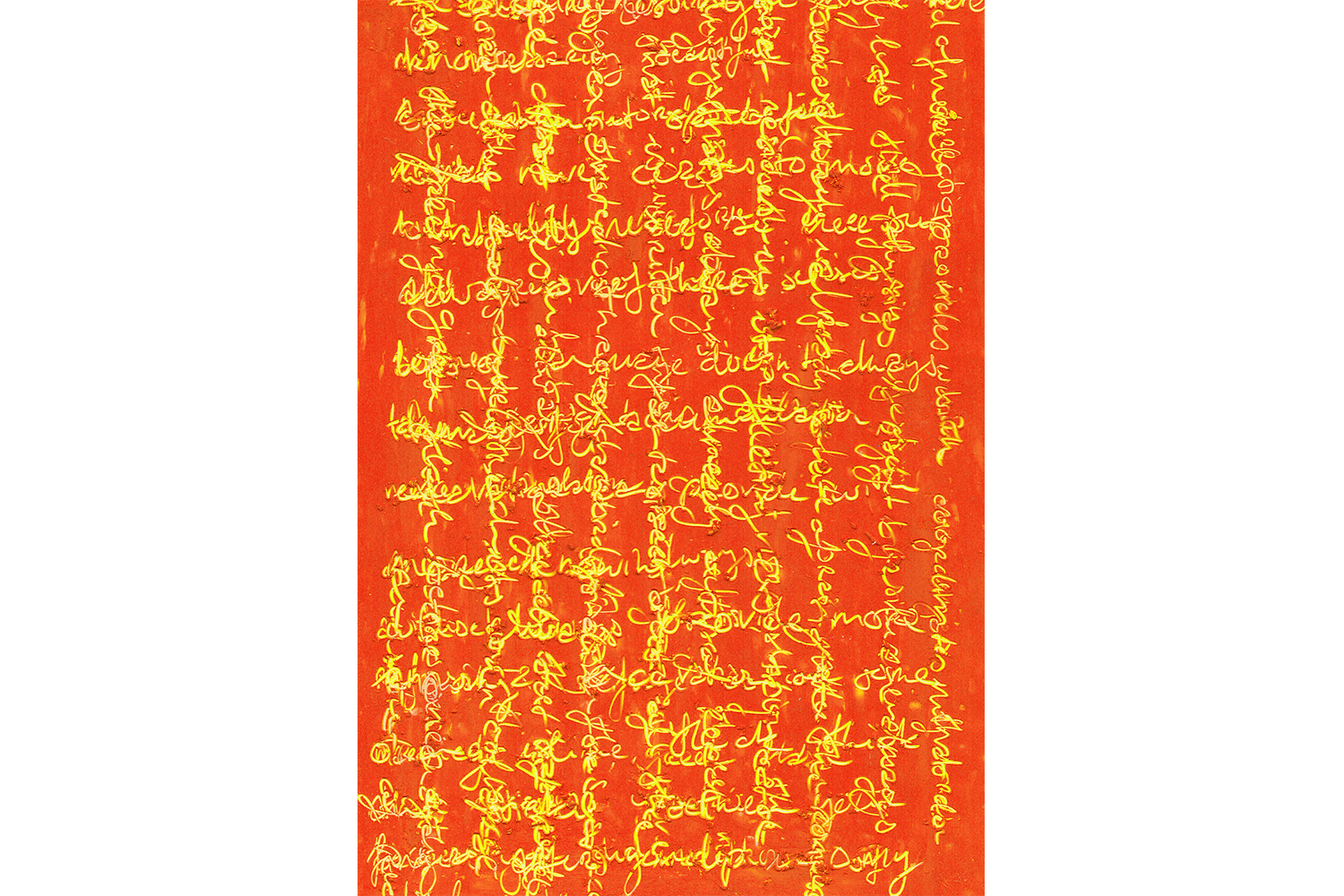

CF: In parallel to your exhibition at LUMA Westbau, you were also showing a series of paintings at Sentiment. These were your first paintings and were “unfinished” — I don’t know if you would use that term though. It’s interesting to me that Moment 2 was shot “twice,” while the paintings weren’t fully completed in terms of the paint applied onto the surface of the canvas. Obviously this brings about big questions about the status of the artwork, but instead of asking “what is?” or “where is?” art it shifts it to “when is?” I’m wondering how you navigate time, time of production versus time of display more specifically, since to me your work tends to make the two overlap.

DJH: I made the paintings at the same time as I was working on the post-production of Moment 2. The two bodies of work have some touching points, though I didn’t conceive of the exhibitions as a two-part single project. Thinking about archival material, about set design, but particularly also about temporality and movement ran through both projects significantly. “Beautiful and tough as chestnut/stanchions against our nightmare of weakness” takes as its starting point screenshots of film scenes inside the domestic space of the main characters. I was interested in the moments where all actors are already out of the shot and all we see is the staged interior, which becomes a staged extension of the characters, specifically in Black lesbian films. I work very intuitively when in production after an extended period of research. With the paintings it was a feeling I had — I could not bring myself to “finish” them. They would’ve lost the sense of movement it creates by leaving parts uncompleted and allowing the pencil lines below to show. This movement was so important to somehow bring to the canvas, especially as the images are screenshots of moving image. I was interested in the relationship between first the layering of meaning and context through the staging process, the selection of props and placing or construction of the set. Then the moment the camera captures this without the presence of a person inside the set, which in itself was only during a few seconds in the films I watched, as well as the film still itself then being a snapshot of only 1/25th of a second — which is then extended again through the process of painting: pushing around oil paint on a canvas, layering it, letting it dry before returning to it, etc.

manuel arturo abreu wrote the exhibition text for this and brought asemic writing into this context so beautifully — an engagement with which we both share in our respective practices. They write, and I really cannot articulate this better: “While the works are in a sense figurative, in another sense they also refuse to engage the western dualism of abstract/concrete, preferring instead a liminal space that is flexible enough to engage not only the overdetermined narratives distributed in mass media (particularly regarding Black gay women and nonbinary people) but also what we might call the ‘asemic’ potential of the marks the hand can make with the oil medium. Figural strategies of absent presences stoke the perception of potential alternatives to value-generating semantic codes which are nevertheless not abstract or ineffable, but in fact registered in the body — in the hand itself, and the oil (which is itself a petroleum record of the cosmic cycle).”

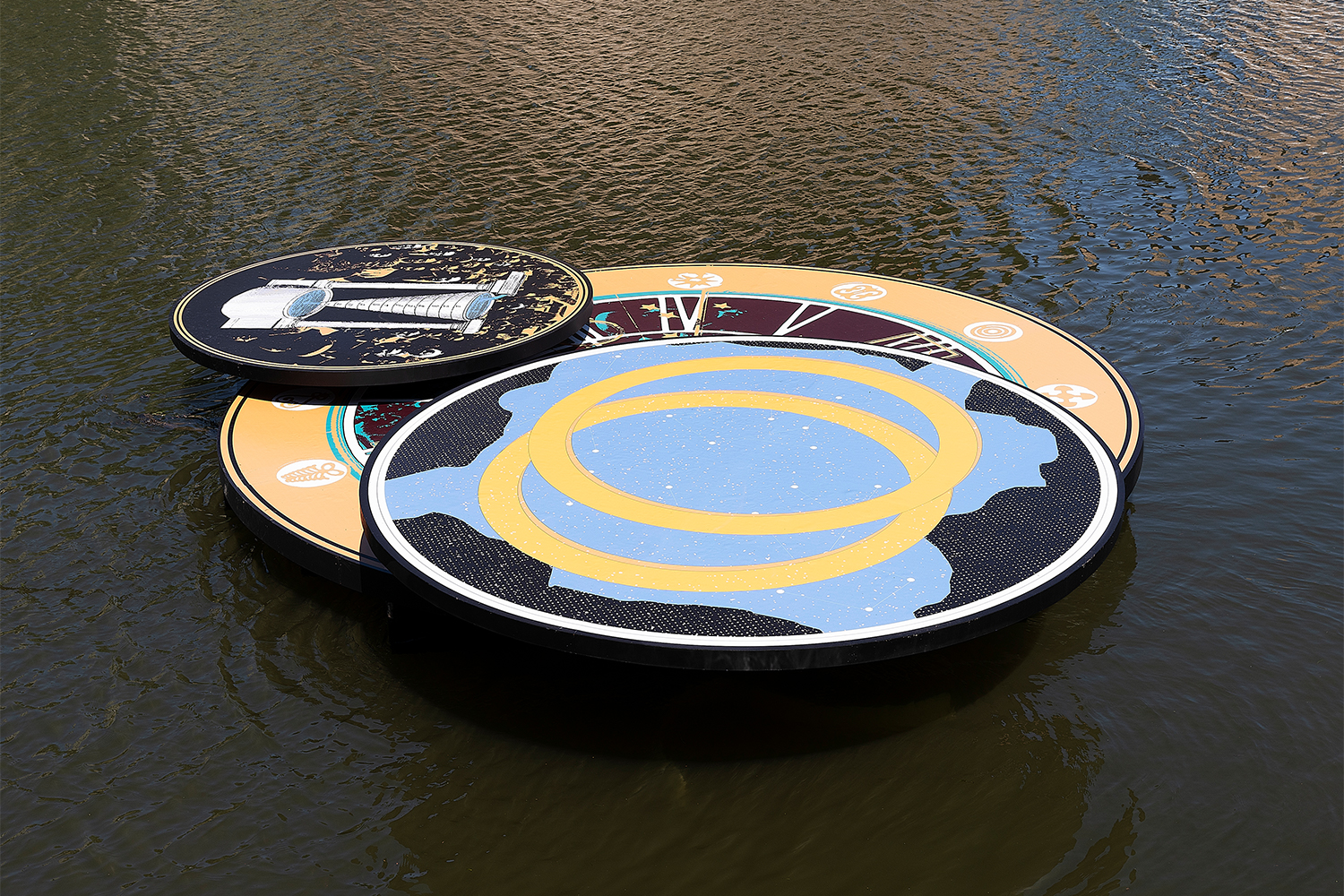

I spoke about staging in the works before, which obviously is instrumental in the display of the work itself again. I started my artistic practice with installation and sculpture, which now throws up the question of “when is?” massively in my thinking between modes of production and display, as the question of time was so intimately entangled in the making of both works. It comes out of the engagement with the specific space — Moment 2, for example, will be exhibited at Cordova, Barcelona, in November this year, in a completely different setup than Luma, where it was projected onto a screen that’s suspended above the corner of a ten-by-nine-meter-long theater stage, which fills the entire exhibition space short of a narrow alley to all sides between wall and stage. I wanted to give weight again to the duration of the performance, to bring the perception of time of the audience closer together to the one of Rebecca and those of us who were behind the camera.

For “Beautiful and tough as chestnut/ stanchions against our nightmares of weakness,” my painting show at Sentiment, Zurich, we decided to paint the walls gray to bring out the colors differently, in thinking along with exhibiting moving image, which is best shown within grays rather than blacks or whites. I was concerned with the opposite of Moment 2, of bringing movement back to the static.

CF: I’m now wondering if you could share with us a bit of what’s coming up for you? As we speak you are in Sicily working with Tarek Lakhrissi on an upcoming film for Istituto Svizzero in Palermo, right?

DJH: Yes — we’re in Palermo, working towards our first collaborative artwork. We’ll be filming in the beginning of August with Jim C. Nedd as our director of photography, who I’ve worked with as a curator for the presentation of his amazing collaborative film with Invernomuto, Pico: Un Parlante de Africa en América at schwarzescafé, Luma Westbau, in 2018, and at Auto Italia in 2020, as well as for a gig at House of Electronic Arts in Basel in 2019. We’ve been thinking about politics of representation, queer desire, the voice in relation to poetry, eruption, and the body. It’s going to be a three-channel installation with an extensive soundscape. The work will be presented at the Istituto Svizzero in October this year.