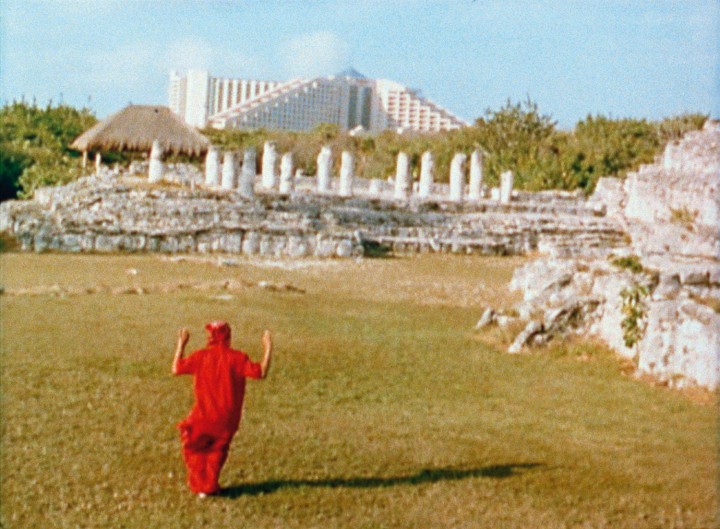

Susanne Pfeffer: For your exhibition “The Recovery of Discovery” at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin you created a new, large-scale sculpture which, despite departing from a prototype of the monument, proceeded to complete itself in the process of its usage. Like the 1878 relocation of the Pergamon Altar from Turkey to Germany, 72,000 bottles of Efes beer, made in Turkey, were transported to Germany. The blue cardboard boxes filled with beer bottles formed the symmetrical steps of a pyramid sculpture in the main hall of KW. By using the monument — which meant climbing the sculpture, sitting on it and drinking the beer — its destruction was immediately initiated. When was the first time you saw the Pergamon Altar?

Cyprien Gaillard: I think I saw the Pergamon Altar the first time I came to Berlin. Maybe it was even with Thomas Struth, possibly in 2001 or 2002. Every time I visit a city, the first museums I visit are archaeological, anthropological and geological — natural history museums. I always try to visit them because I have a general interest in artifacts and fragments, and the question of archaeology in the Western world, which is also a question closely linked to colonialism — this “Why is it here?” question… Looking at archaeology and asking the questions of archaeology in this part of the world also raises the question of colonialism, don’t you think?

SP: I just remember my first visit to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, which astonished me. You could touch and photograph everything, and there were no guards. They even have these no smoking signs, which I liked very much. I have never seen anything like that in a museum before. All the objects were so full of dust and not really taken care of. I normally hate it when nobody makes an effort to take care of a museum. But there, the carelessness and the way everything was stored made it almost come alive. That is also something I wanted to talk to you about. Some museums for contemporary art encompass this brutalism of modernism in a certain way, making a lot of things dead… Do you know what I mean? It also connects to your show at KW. Your idea to use UNESCO as the logo for the invitation card directly links to the idea of protecting something — an artifact, a building, a ruin — in a way that also means to…

CG: …destroy it.

SP: …destroy it, yes. I think, going through all your work in general, there is this moment that you always call “entropy,” which means that if you give things the chance to change they will come alive.

CG: Well, it’s like the double discourse of Western museums… On the one side people say, “Oh, it’s kind of scandalous that these things are to be found here and not on site.” And on the other side there is a more conservative discourse saying, “But if we didn’t relocate them they would have been destroyed by now, because the political situation in these countries is unstable and because the consciousness of ruins arrived faster in Western countries.” So the idea of protecting and conservation came early on in Europe, and, you know, Iraq today is a site for German as well as French and English archaeologists excavating these sites. The map of archaeology is always linked to French or German or Italian or British archaeologists, for institutions such as the British Museum or the Louvre.

SP: I think this whole idea of preservation was also visible in the Renaissance. Artists started to copy ideas from antiquity, and they really started to get a feeling that other cultures had other ideas, which they then tried to understand. I don’t know if that was the first time, but I think maybe it was quite rooted in the European tradition of looking at history. How did you experience the attitudes towards history and preservation in Iraq? Did you meet many archaeologists there?

CG: Yes, I met some Iraqis that were trained as archaeologists. They have, as you were saying, a very interesting attitude towards how preservation is a luxury, and they are not concerned about those things to a great extent. What they like is the idea of Babylon. You would say it’s very colonialist, because nothing is real! But they don’t care. They do not care about what is real; what they care about is the spirit. We care about stones — we’re very materialistic. We are nostalgic and they are not.

SP: What was really visible to you during your trip to Iraq?

CG: The simple fact of the constant looting. People in Iraq have different priorities. They are dealing with life or death — they are not dealing with preservation. We don’t know. The film that I shot in Iraq is not trying to answer these complex questions or to take a position. It is more about how we deal with those ruins and this kind of clumsiness — these monumental errors and this madness of rebuilding monuments from scratch… It’s like when you wake up from drinking alcohol the night before and think, oh, what did I do? We rebuilt these things and now we’re stuck with them. So this is why I tried to bring these monumental mistakes to a personal level. Not as an artist but more as an individual, as a person.

SP: Yes, but in the end it always starts with an individual. You know, being in Egypt and looking at the pyramids, I really had the idea that somebody must have had a vision of these shapes in this landscape. I’ve seen millions of photographs before, but actually being there it was totally different. These dramatic forms in this landscape: so abstract and mind-blowing. The first time I saw them, I thought there must have been one person, one mind who had this idea to build a grave in the shape of a pyramid. I think it always starts with the individual. It’s never the collective who decides to do something.

CG: It touches me to look at 20th-century postcards or images where you see people actually being able to climb on top of the pyramids — considering that you can’t do it anymore. When I was there, with my guide, he looked at the pyramids and told me, “Oh, you’re from France. I was here when Jean Michel Jarre performed his laser concert.” Then he asked me, “Is there a greater composer than Jean Michel Jarre”? And it hit me what a bourgeois I was — to be nostalgic when he was thinking about these things. He is a guide who gives tours every day, who is very close to these ruins, and there he was talking about laser shows and anachronism — Jean Michel is all about the future, about synthesizers. I mean, is there a greater composer than Jean Michel Jarre?

SP: No, but I also think that you are totally right on the one hand — this idea of preserving the most holy thing, this idea of going backwards and not being able to change things. It’s an example of not being able to act in a certain way, because you can’t change the past.

CG: This is why we love ruins so much. Because they tell us we survive, we made it. They are decaying but we survive. I am here and that’s great. That’s what a lot of modern buildings don’t tell you. They don’t tell you where you are.

SP: This might also be linked to the question of the social impact the pyramid at KW had. Did you expect that?

CG: I was secretly hoping it. I was hoping that younger people who have never stepped foot in a museum would come. All these high school kids coming here, and how many times did we see people barfing in the courtyard? Then, just going back to the parents all drunk… I can’t even imagine what they would say coming back home. “Why are you drunk?” “I was in a museum! I spent the whole day in a museum!” What kind of museum would promote such things? I’m still amazed that we were able to pull off such a thing. It’s the magic of Berlin, of your institution, no? It’s great. I don’t know how difficult it was on your side, because I know I was walking in there and it was complete anarchy and smashing bottles and people smoking and drinking, homeless people, unemployed people, people still climbing, this whole idea of broken glass everywhere, and the staff not being able to control it. It’s quite interesting that it was quite a hard show, in the end.

SP: It was! I really had to discuss it with a lot of people. I’d say, “Please, it’s a quarter past 7 and everybody wants to go home, we want to close.” And they would say, “No, please let us stay!” There were always quite personal things going on in the space, which I really liked… And I have to admit I liked that I really had to throw the people out, because people liked to spend time in there. I also realized this in regards to myself; I spent a lot of time there, too.

CG: Me too. I spent so much time there. I never spent as much time in my own show before, as I did at KW.

SP: Same with me. I mean, I always do a lot of tours through an exhibition, but to spend actual time? Not really. That was really nice about the work. You really wanted to stay there — there was socializing going on, talking and drinking. Normally when you look at an artwork or an exhibition you experience the work but then you leave without engaging with it for too long. This was so much more personal. You became so much more involved with the work.

CG: I was really amazed by the proportion it took. There we were serving half-warm Turkish beer… I wasn’t 100% sure that people were going to engage with it, you know?

SP: I really had this idea that it would be the big thing during the opening, and people would stay then, and later people would go in and see the show, but…

CG: …but not engage so much.

SP: …and that is what was most beautiful. The next morning we opened at 12 pm and at 1 pm I came in, and I really had the feeling: What’s going on? There were already people drinking and climbing and just being there…

CG: They also relocated the beer. People were taking so much of it outside and filling, you know, sports bags full of beer.

SP: …taking something from the exhibition…

CG: A fragment…

SP: A fragment of the artwork, like a part of the Berlin wall… I like this idea. I like to imagine that there are thousands of bottles around in Berlin.

CG: I also thought that towards the end all the bottles would be empty and there would be a kind of archaeology of excavating, trying to find the last few remaining full bottles, which was never the case because the pyramid somehow won — it was still standing, which I think is great. I saw people arriving at noon, leaving at 7, every day, trying to kill it and kill it and kill it, but still the monument was standing and had that shape!

SP: There were a lot of people who told me they had already seen images of the pyramid but they were so happy that they came to see it in real life, because of its presence and the smell, the sound. The sound when you climbed up the pyramid, the bottles moving, or the sound later when you walked around it and heard the glass crunching underneath your feet.

CG: Which is interesting, the glass, because it reminds me of Robert Smithson’s work. The idea of glass, or of broken glass, or glass not so far from mirrors, and that sound of crushed glass and, yeah, a lot of things… and the work was quite simple in the end.

SP: For me it modified the idea of land art being outside the institution, in the landscape. I think that with your work you carry the concept of land art into the institution by introducing the exterior — a monument — to the interior and liberating the structure created by the white cube. The sculpture initiated an outside environment inside KW.

CG: Well, for me it’s rather the opposite of land art. It kind of answers the museum of natural history where everything is dead. I always considered the white cube, or the institution, as a dead space. The pyramid also refers to a monument for the dead, originally. But to me it became a kind of land lart work because it deals with rubble and with entropy. I’d wanted to make a work about drinking for several years, but I thought it was so anecdotal — a lot of artists drink and so there is this idea of the romantic artist drinking. By becoming monumental, in a sense it erased the whole anecdotal part of drinking — this just vanished… Because it’s like making a work when you are drunk or something. It’s not so much about you, it’s about an experience. People mention the sculptural elements of drinking, the waste, the physical waste, the physical decay, the presence it takes on. It’s kind of an abstract notion, the idea of being drunk, which you can’t see. But here it is existing formally — it’s physical and it’s a mess.

SP: Then you also feel the shape of things. You have the feeling of high culture and low culture. When people just go there and drink, you might think is barbarian. But look at the building of the pyramids from a historical perspective. With all the slaves, that was also a barbaric act.

CG: And then our pyramid was built with Turkish beer, which is low culture for Germans, because Germans have the best beer in the world. So it’s playing on this hierarchy that exists within alcohol. Good beer, bad beer. An archaeological site in Germany is not as valuable as an archaeological site from Turkey. I wanted to blur the hierarchy between the ruins — somehow ruins should be equal.