Against the tumultuous backdrop of conflict along Pakistan’s northern border with Afghanistan, the ethnic insurgency in the south-western province of Balochistan, and intermittent tensions with India, Pakistani artists are producing works brimming with ideas, irony and provocation. Although State patronage continues to be meager and erratic, art institutions have been expanding, private galleries are mushrooming and private collections are increasing in number and becoming more discriminating.

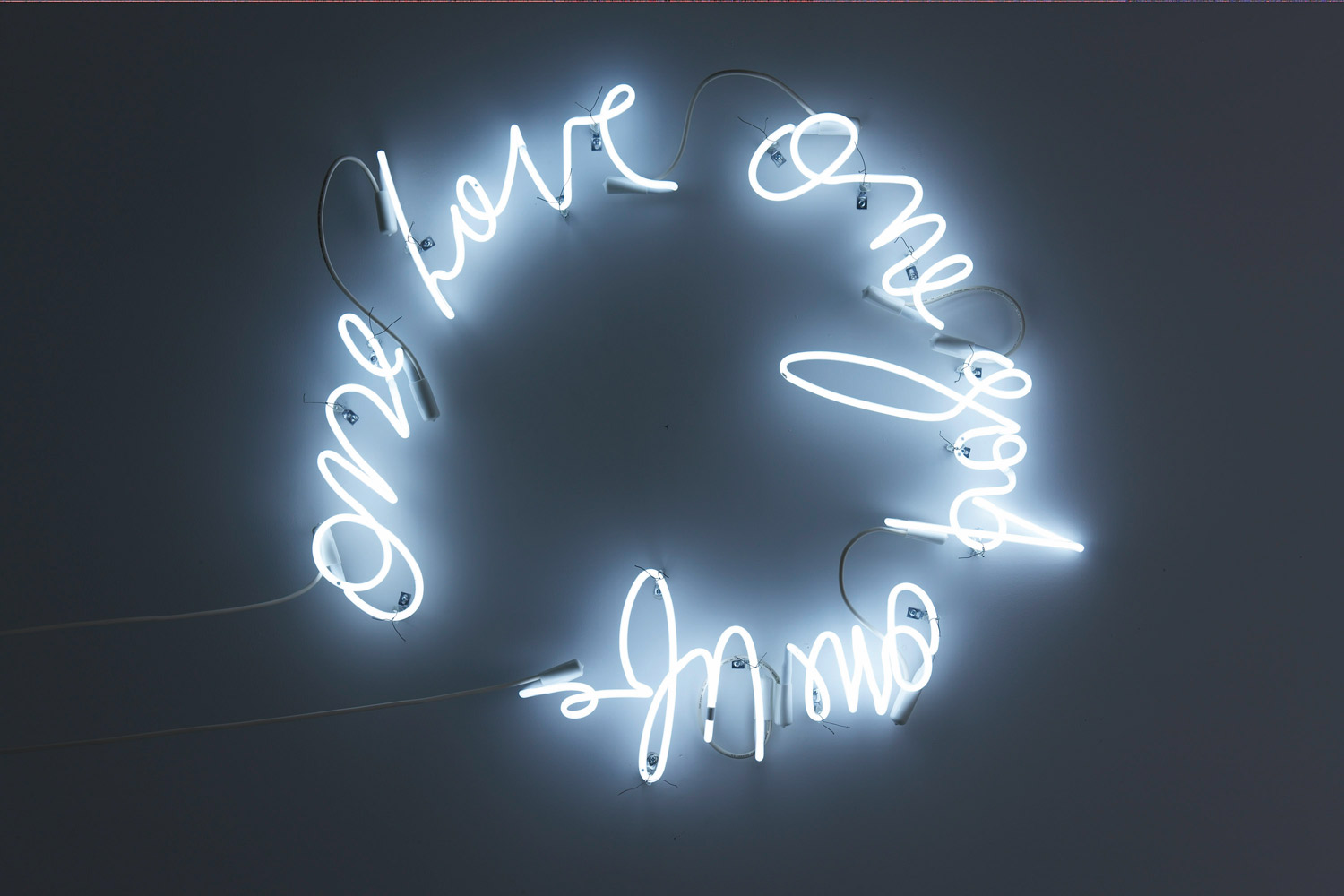

The oldest and most eminent art school, the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore, set up a satellite campus in Rawalpindi (in the vicinity of Islamabad) in 2005. This was in response to the growing demand for professional education in art, design and architecture. While the NCA continues to be the leading Pakistani art school, the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture in Karachi and the Beaconhouse National University (BNU) in Lahore have lively fine arts departments, turning out a keen new generation of visual artists, already being noticed in galleries in Pakistan, India, Dubai, Japan and Britain. Pakistani universities, which once focused only on science and technology, are adding faculties of art and design. Skeptics may point out that this is not because of a sudden public awareness of the intrinsic value of the visual arts, but due to a market-driven need for professionals in electronic media, information networks and the advertising industry. While this may be true, it is also apparent that Pakistan’s social and political uncertainties have bred an animated music, fashion and art scene. No doubt the majority of the country remains agrarian and dirt-poor, but rapid population growth and migration into Pakistani cities, into the Middle East and the West, have injected a new set of imperatives into everyday urban visual culture. Trucks, tractors, rickshaws, motorbikes, donkey and camel carts, food stalls, cinema hoardings, political posters, graffiti, calendars and greeting cards with a profusion of motifs and processes jostle for attention. These form a visual vocabulary understood by the urban masses. City-based ‘folk’ craftspersons employ a mélange of text, image and pattern on trucks and buses; neon lights flashing, every inch of visible surface pulsating with vivid colors, rendered in plastic, vinyl, steel and mirror, they are more like hallucinatory apparitions than vehicles!

This visual subculture draws upon a variety of decorative and pictorial sources that are appropriated in a seemingly intuitive manner, but on closer inspection reveal the needs and desires of various ethnic and social groups. Artists have keenly watched and learned from this spirit of openness and adventure. This has raised the level of engagement between artist and popular audience. For example, when Naiza Khan (Karachi, 1968) transferred works from the art gallery onto the walls of the city of Karachi. This was the series “Henna Hands” (2003) consisting of female figures rendered in henna paste, executed with patterned templates. The students of the NCA (National College of Arts) and the School of Visual Arts, BNU (Beaconhouse National University) worked together in public spaces in Lahore to alter the meaning of existing monuments. These art schools have been consciously engaging with issues of public concern and appropriating all kinds of strategies to initiate dialogue.

A major event in 2007 was the inauguration of the National Art Gallery in Islamabad, which showcased 60 years of contemporary art through twelve concurrent major shows curated by independent curators, while also displaying its own collection. This mega-event reflected two things. Firstly, the presence of a vigorous, innovative and diverse contemporary art scene and, secondly, the paucity of the public collection. An eye-opener for artists, critics and the general public, the exhibitions demonstrated the fact that government disinterest, erratic censorship and lack of patronage had not hindered the development of a diverse, provocative, iconoclastic art movement. Although not a collective entity, this is slowly becoming visible as one of the aspects of a growing urban culture. Private galleries have grown apace in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad, and so far have not been too devastated by the international credit crunch overtaking other businesses. This may be due to the fact that collectors still consider art as a better investment than stocks or real estate. A number of collectors who support the local art scene, though nowhere near as many as in neighboring India, have slowly stepped into the role of patrons, stimulating the volume of activity. The current international visibility of Indian contemporary art, and its ‘red-hot’ activity in auction rooms, has also infiltrated the psyche of the Pakistani intelligentsia within the country, as well as the non-resident affluent Pakistanis across the world. Galleries and collectors in Delhi and Mumbai also discovered the potential of new Pakistani artists, stirring critical interest, instigating exhibitions and a flurry of acquisitions. This interaction, once considered impossible because of the fraught political relationship between Pakistan and India, has flourished in recent years. Pioneered by Khoj International Artists Workshop led by Pooja Sood, the dialogue has occasionally been battered by the ups and downs between both governments, but commerce has been a persuasive factor. The Devi Art Foundation and galleries like Nature Morte, Chemould Prescott Road and Anant have played a crucial role in maintaining and promoting ties. This, in turn, has inspired the setting up of Pakistani galleries outside Pakistan. For example, Green Cardamom in London and Gandhara Art in Hong Kong. Indian-owned galleries in Europe and North America now describe themselves as ‘South Asian,’ exhibiting works of studio artists from the entire Indian subcontinent including Pakistan and Bangladesh. This has widened the window for Pakistani practitioners who were already showing in biennales, triennales, and mainstream galleries internationally, apart from Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad.

Among the most successful of such practitioners is Rashid Rana (Lahore, Pakistan, 1968), who represents the kind of concerns engaging artists who address the world from conservative societies. As he puts it, “In today’s environment of uncertainty we can have the privilege of a single worldview.” He probes the ambiguities that bombard our everyday lives historically, culturally and politically. On another level, Rana, who lives and teaches in Lahore, is constantly referring to traditions, visual and historical, but realizing them through the most sophisticated of digital processes. He is fascinated by the essential un-reality of art, noting that “contemporary information machineries can only produce truths and never simply depict them.”

The genre known as the ‘contemporary miniature’ (or ‘the neo-miniature’) grabbed international attention more than a decade ago with Shahzia Sikander (Lahore, Pakistan, 1969) as its best-known proponent. Since then many others who trained in the same department at NCA in Lahore have dissected the tradition further, turning it inside-out and taking it in myriad directions. Among the more daring are Imran Qureshi, Aisha Khalid, Nusra Latif Qureshi, Hasnat Ahmed and many others. Imran Qureshi (Hyderabad, Pakistan, 1972) teaches at NCA and has spearheaded the transformative path of the miniature in Pakistan. Expanding its diminutive format, both literally and metaphorically, Qureshi translated its sensibilities into architectural installations, video and the third dimension. Aisha Khalid (Faisalabad, Pakistan, 1972) has manipulated the discipline into articulating the predicament of women in a patriarchal society, introducing pattern as an obsessive claustrophobic visual element in her work.

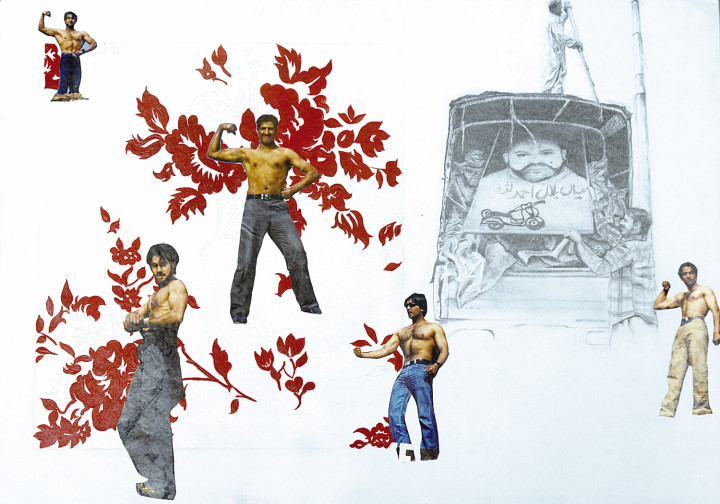

Issues addressing women have been a reoccurring refrain, even though it has been many years since dictator General Zia-hul-Haq departed quite violently from public view. However, repressive laws enacted during his regime still haunt the country. For example, the recent spate of suicide bombings and the return of the Taliban underscore his legacy. A generation later, woman artists harvest domestic craft skills as well as the image of the female body to evolve fresh associations. Masooma Syed (Hyderabad, Pakistan, 1971) has culled human hair and fingernails to weave them into intricate narratives. Risham Syed (Lahore, Pakistan, 1969) looks at ‘masculinity’ and ‘nation’ with a jaundiced eye, exploring stereotypes and their hold on the popular imagination. Mahreen Zuberi (Karachi, 1981) uses the refinements of her miniature training to paint austere, caustic, small paintings that are almost surgical in their approach to male female interaction.

Huma Mulji (Karachi, 1970) and Adeela Suleman (Karachi, 1970), both sculptors with an acute awareness of the velocity of social change around them, look at the absurdities that arise from this phenomenon. Their practice involves working with urban craftsmen, whose skills can be embraced. Huma Mulji’s Arabian Delights, which consisted of a taxidermied camel crammed into a custom-made handcrafted suitcase was ordered out of the Pakistan Pavilion in Art Dubai in 2008. An ironic comment on the “notions of global entertainment,” it also hinted at the forced exoticism of the familiar and may have provoked local sensitivities. Adeela Suleman’s painted metal works allude to protection for the female body in the metropolis. Originating from an earlier series of helmets and motorcycle gear for female pillion riders, the works have evolved into extensions of the body itself: seductive, rebellious, and graphic.