“Before we try to determine the rights and wrongs or the faults in modernity, it is necessary to relativize modernity itself. We need to evaluate it from a distance. It would be difficult to envisage a new society or the arts if we don’t defamiliarize ourselves from modernity by extricating ourselves from it, instead of remaining immersed within.”

— Park Chan-kyong

“The Cold War” and “tradition” are the two terms that best encapsulate the artist Park Chan-kyong’s oeuvre of the past decade. In his early photography, slide projection and short video works from the 1990s to the early 2000s, including Black Box: Memory of the Cold War Images (1997), SETS (2000) and Flying (2005), among others, Park explores Cold War imagery as documented and mediated by public media, such as journalism, television and theater, which delivers a hyper-simulated state of tension, collective hysteria, surreal terror, delusion and ideology. Throughout the following decade, Park Chan-kyong presented highly regarded experimental films, such as Sindoan (2008), Anyang, Paradise City (2010), the feature-length film Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits (2013) and Citizen’s Forest (2016). In these works Park looked closely at South Korea’s autonomous spiritual tradition and attempted to understand how the gradual repudiation of tradition is closely intertwined with the historical turbulence of South Korean modernization in the twentieth century. Shamanism is a particular area of interest, through which Park explores how two disparate lexicons, namely the Cold War and tradition, exist in intricate intertwinement.

In Sindoan (2008), various archival materials, including photography and film footage, are interweaved with video interviews of shamans and other religious people to explore the unseen spiritual engagement and autonomy of numerous small religious communities around the town of Sindoan. In the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897), it was foretold that Sindoan, located near Gyeryong Mountain, was to become the capital of a new dynasty. While under Japanese occupation, Korea saw a spread of utopian thought, exemplified by the Donghak religious movement as well as Sindoan’s newfound status as a sacred and spiritually fecund village. Despite the enormous growth of Sindoan between 1924 and 1975, engendering more than eighty religious communities, many such religions and shamanic traditions around Sindoan were degraded by the clearance projects of the nationwide New Town campaigns in the 1960s, as part of the government’s modernization scheme under the dictatorship of former president Park Chung-hee. By the time the Korean Armed Forces established their headquarters in the area in the 1980s, most of the religious sects had evaporated from the region. Park’s first feature-length experimental film, Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits (2013), continues this critical reading of South Korean modernization through the life and body of Kim Keum-hwa, a renowned Korean shaman born in Hwanghae Province, now part of North Korea, in 1931. Kim is celebrated as a greatly talented spiritual medium, through which ten thousand spirits are animated. Contrarily, Kim’s life and practice epitomize how ideology and nationalism have penetrated, overruled, recalled and exploited tradition for their convenience, positioning Kim to succumb to the subsequent history of oppression that continuously trivialized and degraded shamanic practice as a superstition throughout South Korea’s accelerated modernization process.

In the film Sindoan, the camera observes the now desolate landscape of the village, zooming in and out of the few remaining shelters of believers, overlaying voices from interviews or monologues with depictions of people whose thought resonates with the syncretic cosmology of idiosyncratic religion. Park transposed this religious syncretism into his own fictional scenes of salvation at the end of film, in which some of the wandering young people have an uncanny, hallucinatory encounter with a goddess at the top of a hill. Here, the yearning for redemption finally transforms the sense of void, oppression and pain of the site, the brutal byproducts of modernization. Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits offers a kind of experimental media-spirituality: the rhythms and the movements of the camera become entwined with several performances of gut rituals, nudging these scenes across the border between reality and fantasy. The camera lens recalls the pain and suffering of people through Kim Keum-hwa’s displaced gaze, and Kim, considered an utterly marginal being in society, transforms herself into a pure medium that is able to encounter, identify and emancipate the pains of others. In Park’s narrative, the history of Korean shamanism embodies the violence of the grand narrative of Korean modernization: Sindoan was a place of salvation, and its history of seclusion from colonialism, Cold War politics and nationalism finally disclosed its spiritual power in the unruly lives of its people.

In most East Asian countries, where the process of rapid urbanization and modernization was seen as synonymous with Westernization, upholding “tradition” was a notable part of the modernization process. The 1960s and 1970s can be described as a period when the liberalist South Korea and Taiwan and the communist North Korea and China each selected different memories of history and culture to revive as “traditional.” This was done in order to justify each respective nation’s authoritarianism, with its aim of establishing a long-term dictatorship, and was also used to build and strengthen an ideological national identity. The Cold War era was marked by “recalling” or “summoning” in reverse; that is, while pre-modern culture was claimed as national tradition on one side, the other side would instead claim modern culture. During the developmental stages of the nation-state in South Korea, the master artisans of traditional craftsmanship and techniques were converted into national assets, and only through institutional apprenticeships were the “original” techniques preserved. Through these procedures, private and regional traditions were merged into one authoritarian national system, only to be labeled with ill-defined neologisms of nationalistic character, which in effect rendered “tradition” arcane, further estranging it from the people. The elite, on the other hand, who were the beneficiaries of a modern education, became disinterested in traditional culture, since “tradition” was seen to be associated with the realms of not only the obsolete, but also with an orientalist and nationalistic culture about which modern intellectuals were very skeptical. One of Park’s areas of investigation is whether the prevailing neglect of personal tradition was elicited in part by the critique of orientalism, which was stressed and internalized by Western-centered discourse.

Park’s three-channel video installation Citizen’s Forest (2016), recently presented at the 2016 Taipei Biennial, is a response to two works that inspired him: one is the 1964 poem “Colossal Roots” written by poet Kim Soo-Young (1921–1968), and the other is The Lemures, an unfinished painting by Oh Yoon (1946–1986), one of the renowned painters of the 1980s Minjung art movement in Korea. While the forest as a background references Joseon Dynasty landscape scroll painting, many anonymous, often ghostly figures appear slowly wandering though the woods: a skull-masked brass band, young women in traditional Korean costume, teenagers in school uniform, soldiers, a judge, Korean death angels in black costume, a grandmother, a goddess of childbirth, mountain gods, a headless body, a bodiless head, and so on. Somewhere between life and death, they look lost yet rescued. Departing, they beckon to the outside of the screen. These figures are the nameless lives lost in the tragic chaos of Korea’s modernization — including the Donghak Peasant Revolution (1894), the Korean War (1950–53), the Gwangju Uprising (1980) and the recent Sewol Ferry Disaster (2014). The camera zooms in and out across the three synchronized screens, in dialogue with the experience of spatial structure in traditional Josun Dynasty painting.

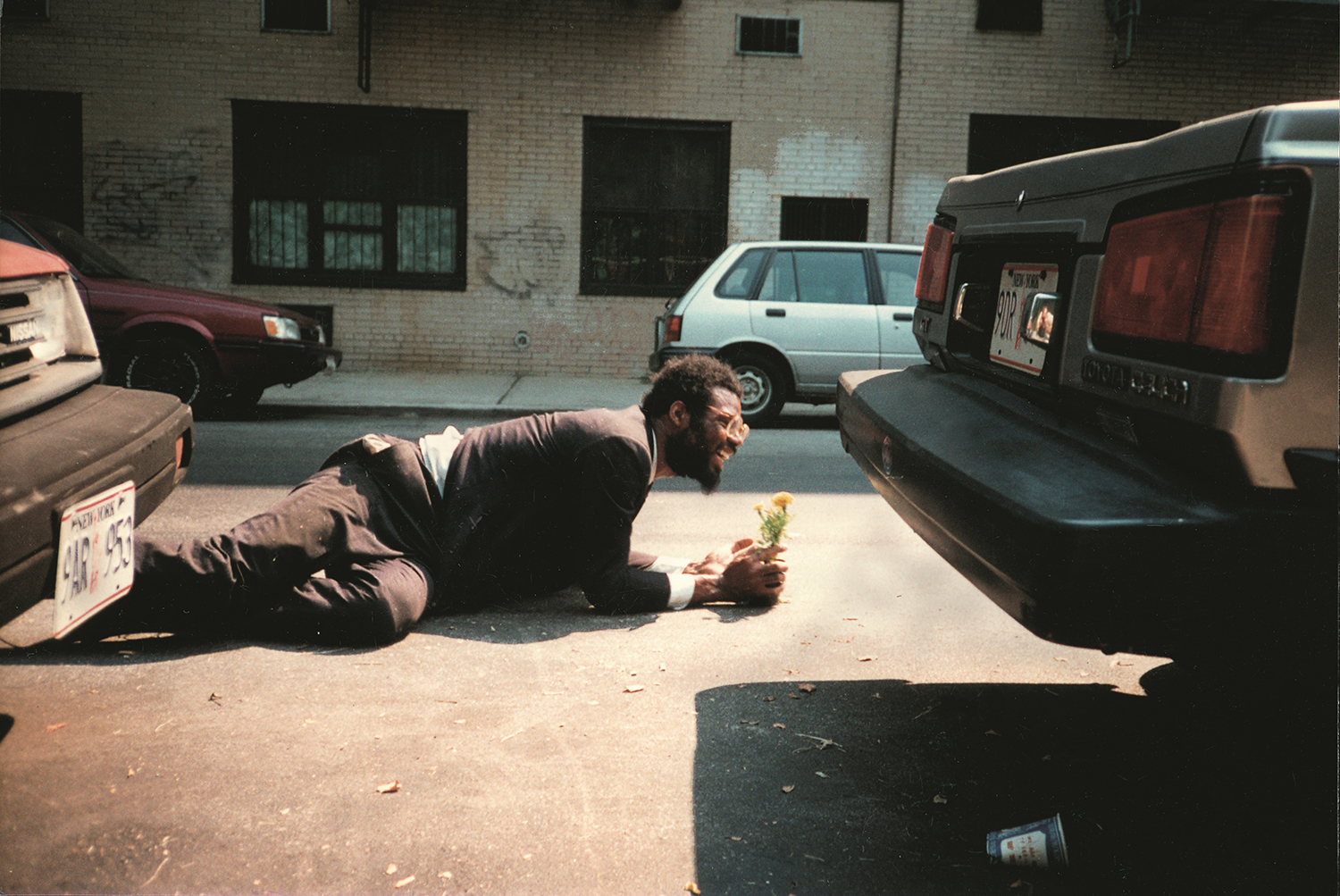

His new installation with slide projection, Way to the Seung-ga Temple (2017), premiered in a solo exhibition at Kukje Gallery, in Seoul. It is a kind of a sequel to Citizen’s Forest. It follows the road to the Seung-ga Temple on Bukhan Mountain, where Citizen’s Forest was filmed. The images in the slide projection shift from secular urban settings to enchanted animistic views as the camera moves deeper into the forest, eventually to the top of the mountain. Both works show the artist’s attempt to approach “tradition” at its heart, a notion often distorted by the commonly bracketed term “traditional culture.” Park’s understanding of the notion of tradition comes through “physical memory” or in living fragments. Using the term “tradition-reality,” the artist relates this notion of fragmented tradition in contemporary times to “Colossal Roots”: “Traditions, no matter how filthy, are good. […] [T]o put up with Korea, rotten country though it is. Rather, I am awed by it. History, no matter how filthy, is good. Mud, no matter how filthy, is good. […] but chamber pots, headbands, long pipes, nursery stores, furniture shops, drug stores, shoe shops, leather stores, pock-marked folk, one-eyed people, barren women, ignorant folk: all reactions are good […]” Just as Kim Soo-young found quotidian objects and trivial belongings to embody a new light of tradition, Park’s recent works find that nameless people’s belongings and soiled things contain a secret enchantment that is in keeping with an intuitive experience of tradition.

Tradition is an emancipatory rupture that liberates the miscellaneous physical remainders of today, no matter how filthy or rotten. Kim Soo-young finds tradition in the subaltern’s physicality, that is, both in the demystification and enchantment of the everyday body from the dirt, the marginal, the real, the unruly. Mundane odds and ends reassert themselves as something real and ungovernable. In this light, tradition surpasses the unresolved and distorted past.

Park Chan-kyong’s latest work, Kyoto School (2017), which comprises an installation of two double projections on adjacent walls — currently on view in the exhibition “2 or 3 Tigers,” curated by Anselm Franke and myself at Haus der Kultren del Welt, Berlin — attempts an ambivalent understanding of the controversial Japanese history of the Kyoto School and kamikaze. The Kyoto School, which began roughly in 1913, was a philosophical-academic movement around Kyoto University, which sought to assimilate Western philosophy and religious ideas and to use them to reformulate thought and morality unique to the East Asian cultural tradition. Though it is hard to group them into a single philosophical affiliation, many earlier academics of the Kyoto School were preoccupied with theories that emphasized authentic and distinct Japanese inherency vis-à-vis the West, and established Kegon Falls as the emblematic image to represent the philosophical and political spirit of Japan at the symposium “The Standpoint of World History and Imperial Japan,” organized by Japan’s foremost literary monthly Chūōkōron on November 26, 1941. In Park’s Kyoto School, the artist juxtaposes a variety of slides of Kegon Falls with texts excerpted from private journals of kamikaze pilots. For the Kyoto School, Kegon Falls represented the sublime, and symbolized their idea of assimilating the world into the spirit of Japan and the essences of Eastern philosophy, such as resoluteness, sacrifice, the absolute, and the solemnity and resplendence of the Avatamska in Buddhist thought, or, in Japanese, Kegon. The symposium emboldened the Kyoto School, such that it blatantly pronounced the Pacific War as well as the colonial invasions of various Asian territories to be honorable, which in turn inspired Japanese youth to offer their services as kamikaze pilots.

In this work, Park invites viewers to rediscover the kamikaze, the imperialist youth of Japanese militarism, as cosmopolitan subjects full of intellectual desire. Their thoughts via their journals give a strong sense of Western philosophical and literary influence; they exalted the creative act of writing poetry, and, in their ability to engage with foreign modern ideas, showed a profound depth. Despite the critical role the kamikaze pilots played in Japan’s hegemonic machinery of war, the contents of their private papers substitute our assumption of brutal nationalism for a complex, ambivalent, antinomical desire for reciprocity with the world. What is revealed here is the subverted influence of an abstruse metaphysics imposed by scholarly purity far from the battlefield. The complex and less articulated cosmology of the spirit of Japan, which the Kyoto School strived to realize with the symbolism of Kegon Falls, is more obscure. For when it comes to thinking about the relationship of the Kyoto School with the rest of the world — the sublime connotation of the Kegon Falls, wherein the Japanese spirit meets the grandeur of world history — the image is distorted by high-spirited patriotism. The splendid mists from the gushing waters of Kegon Falls, which the Kyoto School imagined as the struggling particles of world history, foretold the extreme sacrifices, the shattered lives that faded into Japanese militarism, and finally, ultimately, the fall of an empire. Moreover, the internal paradoxes of the kamikaze fighters, the collisions of reason, the conflicted worldviews, and the troubling gaps between morality and the brutal demands of totalitarianism, all converge in an image of a whirling, watery vortex.

Park Chan-kyong persists in seeing these unresolved and anomalous histories as an archive for rethinking Asian modernity. Through stirring and intellectual works, Park pursues a hauntological understanding of the extremely violent and oppressive trajectories of East Asia in the twentieth century. In his radical contestations, he keenly appreciates the unruly individual spirit found in unyielding believers, shamans, obsolete images, real folks, and the written notes of young kamikazes. Ultimately, he offers spiritual salvation to a society deeply scarred by numerous historical struggles and traumas.