Legendary postwar artists in Japan have seen a recent resurgence of attention. Last year, the exhibition “Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented a spectrum of genre-straddling avant-garde practices that emerged as artists drew on the energy of the rapidly developing and ever-changing metropolis during this period. Around the same time, the Guggenheim Museum in New York spotlighted Gutai in response to renewed interest in artistic expressions centered on the body. Gutai continues to be introduced as the representative avant-garde movement of postwar Japan, as confirmed by the exhibition “Explosion! Painting as Action” that took place last year at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm and which gave prominent space to Gutai artists Kazuo Shiraga and Shozo Shimamoto. This public and institutional interest has been mirrored by commercial gallery exhibitions like “The Masked Portrait Part II” at Marianne Boesky; “A Visual Essay on Gutai” at Hauser & Wirth; as well as “Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha” at Blum & Poe, which, in addition to their main gallery in Los Angeles, has just opened an office in Tokyo. Additionally, a recent exhibition at Punta della Dogana — the second venue of the François Pinault Foundation after Palazzo Grassi — featured the Japanese group known as Mono-ha alongside works by Italian artists from the Arte Povera movement. Prominent artists who emerged between the 1950s and the 1970s — a time when postwar Japan entered a period of rapid modernization — gave birth to unique and unconventional forms of art against a backdrop of ideological and social change.

On March 11, 2011, Japan literally faced a ground-shaking moment when a disastrous earthquake hit the Tohoku area. Despite official statements, the situation generated by the tsunami and the ensuing nuclear power plant accident is still far from being settled. We in Japan have been faced with our own complacency and negligence as a result of having prioritized energy-dependant development — despite being the only nation in the world to have suffered nuclear attacks in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. “What shall we do from here?”After the earthquake, the public mindset has been weighed down by fundamental questions of this sort.

Architects were the swiftest players in the wake of the earthquake. They proposed plans for places in which communities could be regenerated, such as a project to build a “home-for-all” — where earthquake victims could gather — that was presented at the 2012 Venice Biennale for architecture. Musicians also united in their aim to raise large amounts of aid for victims through concerts and festivals. Meanwhile, artists faced an overwhelming question: in this time of crisis, what can art do? For many, it took more than two years to chew on and digest this question, the output of which we are finally coming to witness only recently. After a string of direct actions, such as Yoshitomo Nara offering a drawing with “No Nukes” signage available online for free download, artists in Japan have begun to show a more socially concerned perspective.

Born in 1968 in Kagoshima, Tadasu Takamine is known for his keen sense of criticality toward the systems of control and oppression that operate within contemporary society. A theatrical methodology forms the basis of his practice, through which he exposes this critical perspective. He challenges large-scale systems that structure society by using the “I” as intermediary. For Takamine, who started off his career as a performer, the intervention of his own body is paramount. His latest solo exhibition, “Cool Japan” at the Art Tower Mito in 2012, critiqued the contradictory move taken by the government to possibly restart the halted nuclear plants despite unresolved issues. In particular, Japan Syndrome (2012), a video work showing reenactments of conversations in shops on the topic of radiation effects, was effective in underscoring how the sense of distance and response to the nuclear accident varies among persons and regions. While the work is based on actual conversations, it develops within a minimal setting with anonymous figures; unlike documentaries in which specific individuals are depicted, viewers are able to identify with Takamine’s nonspecific protagonists. Also presented on this occasion was a multi-media installation in which children’s voices resonate against each other and Takamine himself appears on a video monitor, brandishing a metal pipe. The performance, charged with anger and driven by impulse, can be taken as a gesture that uproots old values while simultaneously plowing fertile new ground.

Born in 1975 in Tochigi, Koki Tanaka, who is currently representing Japan at the 2013 Venice Biennale, questions new relationships between people in post-quake society. Tanaka is interested in unconscious acts of the everyday as well as responses to certain restricted circumstances. He attempts to visualize hidden meanings and alternative interpretations of events by employing various media such as video recordings of performances, live sessions, photographs and texts, presenting them in a composite form. Currently residing in Los Angeles, Tanaka was not in Japan at the time of the crisis, but like many, he shared news through social networks. Since then, Tanaka’s practices have been centered on the cognition of experience, for example, by exploring what it means to “experience” something or questioning one’s capability to understand what someone else has experienced. He gives “tasks” to people so that they develop a cooperative process: nine hairdressers try to give a haircut to one person; five pianists compose a music piece using only one piano, and so on. The idea of individuals engaging collectively in a task becomes, in turn, a metaphor for the collaborative efforts through which people have tried to overcome difficulties in the aftermath of the quake. Tanaka also conducts what he calls “collective acts,” which consists of gatherings of individuals brought together in order to act within pre-established settings. It is only natural that collective acts as described by titles such as Swinging a Flashlight While We Walk at Night or Talking About Your Name While Eating Emergency Food overlap with images of people engaging in anti-nuclear protests or getting ready for evacuation. Given that these somewhat abstract group actions can be interpreted in accordance with social situations and contexts, they also become common platforms where larger and broader audiences are encouraged to rethink the status quo.

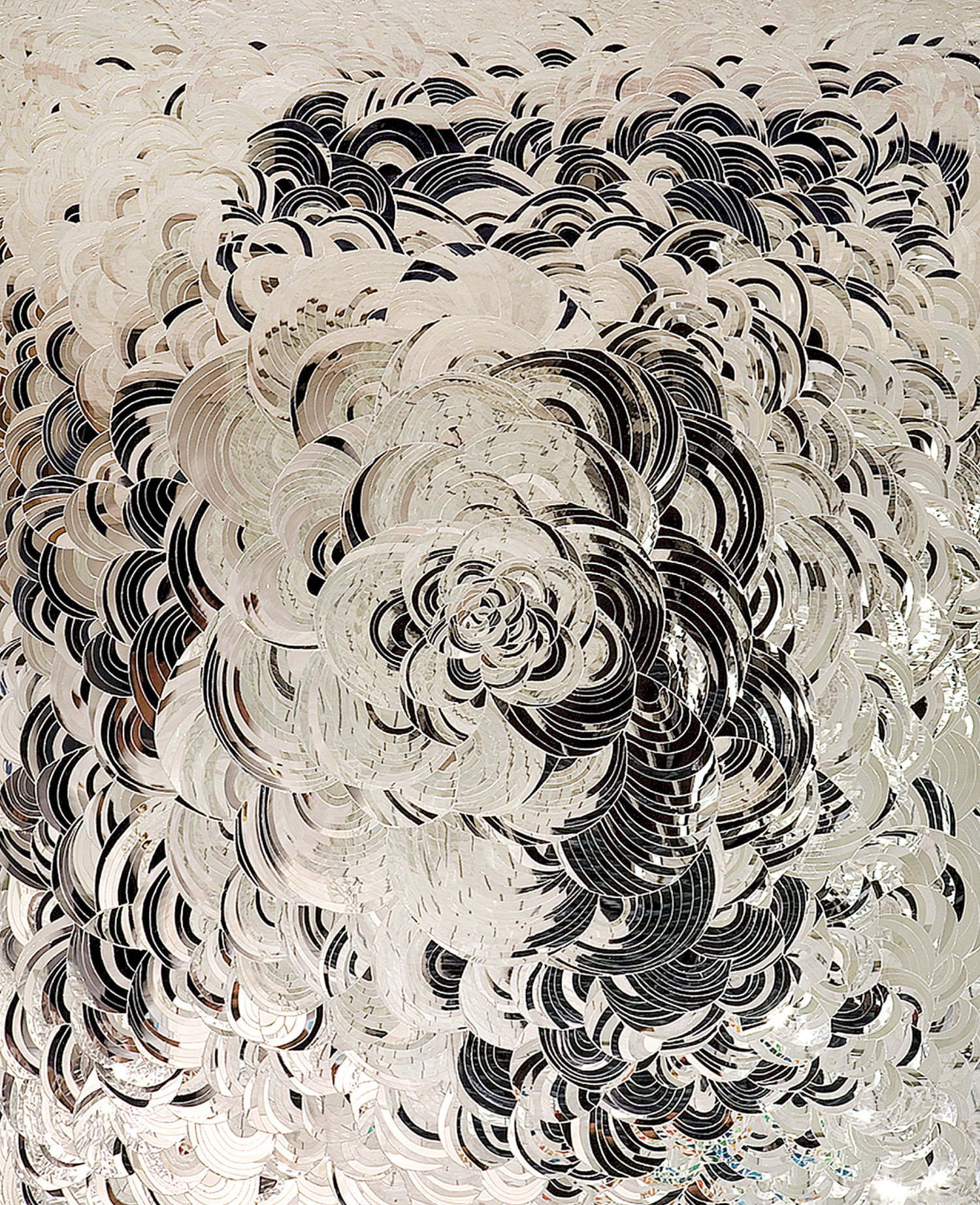

The media has repeatedly aired footage of the damage done by the tsunami. Images as such become rooted as collective visual memories, which at times can unexpectedly link to other ideas. Somewhat similar is the practice of Teppei Kaneuji, born in 1978 in Kyoto, who assembles unrelated paraphernalia — for example, plastic figures and various sundries — to give birth to new objects and images. Dipped in creamy plastic resin and covered in white starch powder, the objects in the series “White Discharge” have been stripped of their intended purposes and individual meanings. While visualizing a sense of absurdity, the objects also celebrate a sort of Dadaist randomness. Now that the destructive force of nature has been imprinted in our collective psyche, it is possible to interpret Kaneuji’s intrinsically disparate objects as fragments of destruction.

In 2011, Kaneuji designed the stage set for the theater play “Kaden no yo ni Wakariaenai” [We Can’t Understand Each Other Like Household Appliances], directed by playwright Toshiki Okada. The combination of Kaneuji’s art with words, as experienced in this collaboration, showed potential for an even stronger allegory of the present. In fact, Okada’s work is characterized by the use of youth slang and physical expressions that evolve from exaggerated everyday movements. His unique methodology touches on multiple genres such as literature, art and choreography. The rambling conversations and senseless bodily movements that inform Okada’s works are brought together in order to create a rhythm in which fragments of daily conversations gradually reveal the contours of social events. The linguistic and bodily world of Okada and the visual world of Kaneuji are an exquisite match; they merge and supplement each other. With the earthquake disaster as impetus, and the urgent social context as a common layer of understanding, their work becomes a stage wherein both artists and audiences embark on a collective venture of interpretation.

Like Kaneuji’s works, the landscapes that unfold in Masaya Chiba’s paintings are born from strange connections drawn between quotidian objects. Born in 1980 in Kanagawa, Chiba begins by juxtaposing common objects and sculptures he has made from clay and wood with landscape photographs, which he then presents as installations. On other occasions, Chiba starts by inviting others to share the experience of an action — for example, the burning of a hut. He and his friends take a photo of the scene, which Chiba later renders in a painting. In this sense Chiba’s oeuvre is made up of process-based combinations of fictional scenes, documentary elements and paintings. Since March 2011, the stories in his paintings have taken on an allegorical aspect. In one painting, a pet turtle appears to be cheering himself on in his cage, a closed world that is reminiscent of evacuation housing. In others, landscapes are smothered in liquids that evoke toxic substances. By depicting personal worlds in this manner, Chiba discharges emotions against social crises and unrest. Another important aspect is how Chiba’s paintings are often propped up on unstable surfaces. Working as a direct metaphor for the shaky ground of contemporary society, these works reflect the artist’s attempt to both deconstruct and probe for a newly emergent form of painting.

Collective acts are born from the desire to consciously engage others. Since the mid ’90s, Tsuyoshi Ozawa, born in 1965 in Tokyo, has spearheaded a movement dedicated to participatory practices while paying particular attention to aspects of everyday life. His portable gallery project called Nasubi Gallery (1993-ongoing), and his portrait series “Vegetable Weapon” (2001-ongoing), which shows people posing with inoperable guns made from vegetables used in local specialties, are examples of inserting the everyday into art, a practice Ozawa has continued to pursue in order to expand the boundaries of artistic expression. In the face of post-quake reality, however, Ozawa appears to have become more socially oriented, taking into consideration the place occupied by artistic practices in the real world. Ozawa’s characteristic sense of humor and theatricality represent the contemporary condition in an allegorical manner. His newest work, The Return of Dr. N (2013), revolves around the fictitious character of Dr. N, modeled on the noted bacteriologist Hideyo Noguchi (1876-1928), a local hero of the disaster-stricken area of Fukushima. Although Noguchi was a truly international figure, there was also a human dimension to his character. Coming from a poor family of farmers, Noguchi worked hard and was able to succeed in the field of science. However, he was also a lavish spender and was always in debt. Ozawa contacted billboard painters from Ghana — the country where Noguchi died while he was doing research on yellow fever — and commissioned to them to depict the life of “Dr. N.” Today’s renewed interest and reconsideration of Fukushima is the main reason behind Ozawa’s goal. His process of interpreting Dr. N becomes an invitation to a dialogue about the meaning of translation — and even misinterpretation.

Born in Okayama in 1978, Motoyuki Shitamichi uses photography as a tool to capture the power of imagination that inheres in ordinary people and places. For his series “Torii” (2006-2012), which received much attention at the 2012 Kwangju Biennale, he photographed the remains of torii — the traditional Japanese gate built at the entrance of or within a Shinto shrine — that were built in territories formerly under Japanese rule. In one photograph, a torii lies stranded in a dense tropical forest, while in another, a torii has been laid on its side to be recycled as a park bench. Shitamichi explores the different ways in which these symbolic and historical relics — marks of the past, which are now destroyed, forgotten or abandoned — have been perceived and transformed by people of the present time. In his recent series “Connection” and “Bridge” (both 2011-ongoing), the artist photographed the small “bridges” people make by placing boards and other leftover materials over street gaps for purposes of convenience. Shitamichi also borrows the actual objects from the residents and uses them in his installations; apparently his policy is to return them after the exhibition ends, although in most cases they are given to him. Shitamichi awakens both himself and his viewers as he questions how creativity takes shape — in other words, what is this thing that we call “art.” However trifling such gestures may be, they are part of our daily life.

The practices of the aforementioned artists have common elements — not in the way that they expose urgent social situations in sensational ways, but in the way they embrace the pain that permeates post-earthquake society. Each in their way endeavor to build social relationships through artistic practices that make current situations shareable by way of theatrical metaphor or humor. These artists, as individuals yet also part of a society that is ever more global and connected, continue to build intellectual platforms based on dialogue. Art in Japan is beginning to attain a certain democratic aspect by having incorporated elements of participation and ordinariness. The earthquake, and the damage it has done, has been instrumental in encouraging people to reject the materialism that plagues Japan, and it has prompted artists to renew the link between their practices and society in order to strengthen and enrich both.