Umberta Genta: Do you have an obsessive personality? I can’t help wondering about it when I look at the extreme perfection of your work.

Charles Ray: I would say someone might say that I was obsessive, but really I am not.

I have discipline and persistence. Obsession is undisciplined and mindless, two qualities that are out of place in good artwork — or any work, for that matter.

UG: Does your meticulous approach manifest itself in your daily life?

CR: It depends upon what vantage point you view me from.

UG: Compared to other artists, your output seems very thoughtful but also very spare. Is that a function of being a perfectionist, or is it more of a deliberate production strategy?

CR: My sculptures are born from a personal necessity to create and communicate; other aspects of this drive are secondary.

UG: Do you think this “slower” output has had an impact on your career?

CR: Aspects of my previous answer address this question. My output follows the essence of my sculptures. Output and production are not strategies; they are necessary or rather emergent qualities of my relationship to work.

UG: How do you know when a work is finished?

CR: That’s a good question. In the past many people have commented that I am slow.

I have often thought that I take a long time to produce a work. Recently I am beginning to understand that one does not necessarily have to take time but can use time to create a work. If you want to think of time as a river eroding stones, you can begin to see how time itself can be used to create a sculpture.

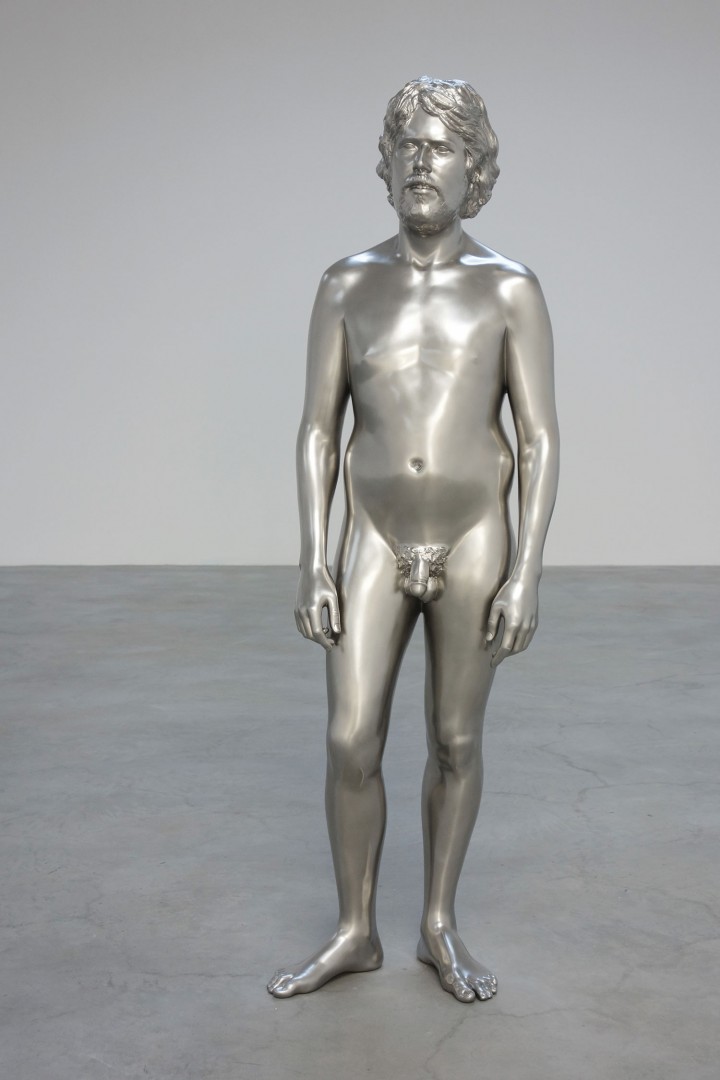

UG: From your earliest works to Oh! Charley, Charley, Charley (1992) to more recent pieces such as Light From the Left (2007), your own image reigns supreme. When researching your work, I sometimes couldn’t distinguish you from your sculpture! Has anyone mistaken this for mere narcissism?

CR: I’m sure they have, but I never make that mistake myself. They are sculptures and they are directed towards viewers, and that structure between the work and the beholder breaks the mirror of self-absorption.

UG: It must be challenging to reproduce yourself so realistically. Have you encountered any difficulties?

CR: No. Realism is structural rather than emotional.

UG: I recently spent a little time in L.A. My impression was of a place where much of one’s life is concentrated around the home. Do you think that’s accurate? Why are you based in L.A.?

CR: I’ve always tried to live near water. I grew up on lake Michigan, and when I came to LA I gravitated towards the beach. I now live a few short miles from the Pacific.

UG: I see a shift in your work from expressions of completed actions to incomplete actions. One of the new works at Matthew Marks is a man lacing his shoe, but there’s no shoe. Do you want viewers to complete these actions in their minds?

CR: No, my sculptures are seldom only about the spark of inspiration that ignited them. Shoe Tie (2012) came from an idea I had about a ghost. I do not believe in ghosts, but if they did exist and a ghost wanted to tie his shoe he would not need to have a shoe. This simple observation led me on a path or trail to make this work. The act of making the sculpture and the sculpture itself create a sort of meaning machine that, when the work is good, is hard, if not impossible, to turn off.

UG: In the ’90s you made a sculpture of a giant woman dressed in a corporate outfit (Fall ’91, 1992). Do you still see women as “giants” today, or do they have a more human scale?

CR: I disagree that the sculpture you are referring to depicts a giant woman. It simply transforms the viewer into a very small person.

UG: What does a subject need to embody in order for you to feel motivated to create its sculptural version?

CR: It does not really work that way. The true nature of the subject is rarely there at the beginning.

UG: In some of your works depicting boys, Boy with Frog (2008) especially, I get the sense of being in a transitional state — of being on the cusp of adult consciousness. I guess this consciousness happens at different ages for each of us. What do you recall about being a boy, and what meaning do you attribute to that period of your life? Do you see yourself in that boy?

CR: I don’t see myself in that boy, but I certainly look for the boy that I no longer am. The other day I was fondly thinking of a particular mistake I made as a young kid. It was then that the impossibility of time travel finally came home to me.