When my own doors shut, I can freely enter whatever world I want.

–– Amos

Awe-inspiring concrete tower blocks, colossal against gray skies; traces of human presence trapped in weather-worn Brutalism; some soft synthesizer Muzak. Cécile B. Evans’s Amos’ World: Episode One (2017) adopts the format of a typical family TV sitcom, yet one shorn of the glow of halcyon homes. The residents of this world –– the Secretary, the Nargis (a group of three CGI daffodils of human scale), Gloria, and her mother –– are all bleakly boxed in. Disrupting a TV genre that brazenly entrenches mainstream values, Evans’s latest work of video art critiques our digital era by revisiting its prehistory.

Amos’ World premiered at Art Basel, where it was screened inside a Brutalist-style three-story structure, seemingly transplanted from a high-rise into the twenty-five square meters of Galerie Emanuel Layr’s fair booth. Comprising six windows through which to view the projection, this stout construction captured the oddly soothing quality of a bunker’s solitary confinement. Like her earlier immersive installation titled What the Heart Wants (2016), Evans’s latest work challenges the impermeability of the screen by means of a walk-in structure –– a bridge connecting actual space and the simulacral reality of the projection.

More than simply a pragmatic solution to postwar demand for cheap, high-density public housing, Brutalist architecture was originally designed to cast the dazzling conditions of modern life into consolidated, comprehensible form. In an article from 1954, Alison and Peter Smithson imagined the movement as something “mysteriously influenced by industrial techniques, the cinema, supersonic flight, African villages, and old tin cans.” If Brutalism embraced mass production, vertical cities and the unvarnished materiality of raw concrete, it did so in order to expose the newly technicized reality it was based on, as well as to shape the citizens of a modern society yet to fully arrive. Architecture has always held a special place in modernity’s “reprograming” of mind and body, whether in Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967) or Ben Wheatley’s recent screen adaption of J. G. Ballard’s dystopian novel High-Rise (1975). Amos’ World joins the ranks of such cultural criticism inasmuch as it presents the image of a system (our system) haunted by the delusions it has summoned.

Amos’ World tells the story of Amos and the tenants of a faulty housing project he has designed. A puppet with a CGI face, Amos is a caricature of an architect, complete with a black turtleneck and a tasteful 1950s study bearing all the typical trappings of intellectual authority. Constantly confusing his architectural project –– long realized and by now in decay –– with a utopian vision for the future, Amos inhabits a space outside linear time. From an argument he has with the Weather (voiced by Cécile B. Evans), one can infer that he is driven by a very modernist hubris to remold mankind by superimposing a framework “containing […] and, above all, retaining” the people living in it (one of Le Corbusier’s “machines for living” is referenced in the opening sequence). “I build doors for them” Amos declares solemnly, “so that they can enter their own worlds.” Apparently unable to leave, Amos’s tenants are trapped within his closed circuit.

Once the camera zooms in on the life of the inhabitants of Amos’ World, a stark disconnect between internal and external realities grows apparent: fashionable, minimalist furniture; a modern kitchen; TV flat screens mounted on walls of raw concrete; and a large window overlooking a contemporary cityscape. Whereas the window at first suggests openness to the outside world, we soon register its imprisoning quality. Evans’s static camera shots repeatedly align window and camera frame –– for what is a video screen but a window that doesn’t open outwards?

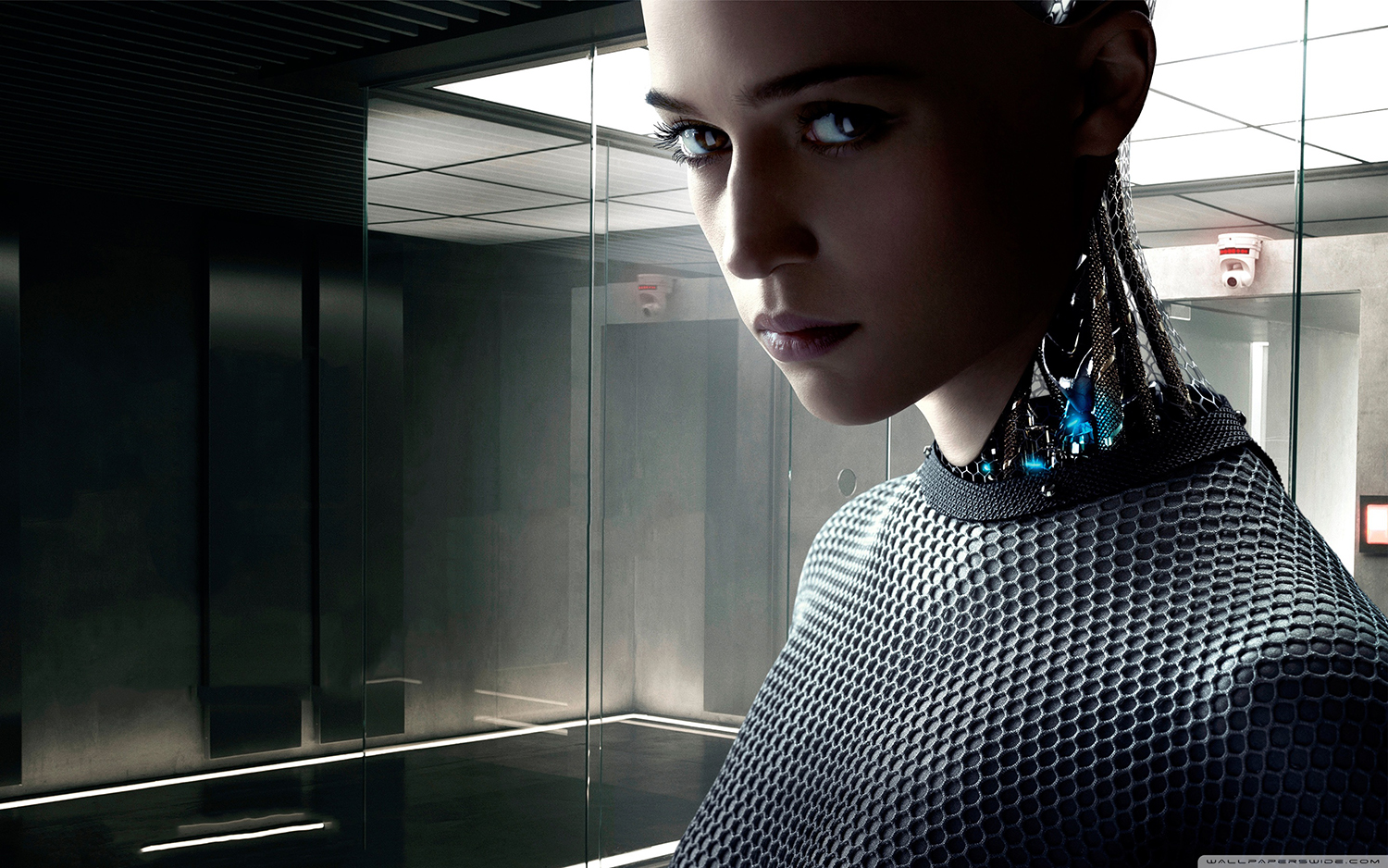

The Secretary is one of two flesh-and-blood residents we meet in Amos’s building. She is a reincarnation of Joseph Weizenbaum’s secretary, an unlikely footnote in the history of artificial intelligence revealed in Adam Curtis’s HyperNormalisation (2016). Weizenbaum’s secretary fell for ELIZA, just as Evans’s Secretary falls for CGI daffodils. In Amos’ World we first encounter her lying on her bed in a blissful dream state surrounded by the Nargis –– a name referencing the botanical Genus Narcissus, and an oblique therapeutic diagnosis.

Weizenbaum developed the original ELIZA in 1966 at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory as a language processor, or chatbot. Frustrated by what he saw as his colleagues’ overly optimistic expectations for the field, he conceived ELIZA as a parody of an AI, simulating speech based on a conversation strategy developed by psychotherapist Carl Rogers. Conjuring deceptively intelligent responses by simply reflecting patients’ statements back at them, ELIZA created an illusion of intelligence and empathy.

At a time when language was still a uniquely human capacity (before chatbots were found conversing in a language entirely of their own), ELIZA was little more than an interlocuting echo chamber. Yet despite Weizenbaum’s insistence to the contrary, many early users attributed humanlike feelings to the program. Among the testees who would sit with ELIZA for hours discussing their deepest feelings was Weizenbaum’s secretary. Amos’ World develops the Secretary’s story still further, sharing intimate confessions without ever moving her lips. Like her historical prototype, she is caught in a looping internal monologue.

Like the Secretary, Gloria seems to have abandoned life outside the building, living alone in another of Amos’s apartments with a CGI swallow she refers to as her mother. A former actress, Gloria exists in the shadow of her image which, having detached itself from her, roams the world more freely than she could ever hope to. Beyond allegorizing another malady of our digital world, Gloria’s narrative holds the promise of a loving reunion with the Time Traveller, a rebellious girl who escaped the building long ago and whose return heralds the Brutalist fortress’s demise.

As the film score rises to a crescendo, the threads of each character knit into a climax, with the architect in tears and Gloria pressing the window glass –– about to burst her filter bubble. Yet the only characters to escape are the Nargis, boarding an airplane with a floral victory salute. As strange as this last scene is, Evans carries it off. Drawing on a repertoire of cinematic tropes rehearsed in countless season finales, the artist skillfully pushes our buttons.

Seeking to expose the ways in which our media –– images, projections and disembodied voices –– leave us paralyzed, Evans resorts to a two-fold strategy of immersion and alienation. By injecting a comic release in the form of a Brechtian “turn-off,” she provides for a minor disruption to the end of “Episode One.” Yet the immersive lure of the spectacle prevails, and in doing so poses a problem: How far can Evans’s cultural critique succeed when rendered in the very same pop cultural tropes she sets out to critique? Can reproducing a pattern ever escape entrenching it further?