In New York everything happens quickly: three years are an era, a period long enough to test an entire generation, to glorify the handful of victors and jettison the multitudes of the vanquished. In 2003, art journals and newspapers like the New York Times had barely introduced a new group of young gallery owners who were setting out to conquer the city — among the others Michelle Maccarone, Daniel Reich, John Connelly, Oliver Kamm and Zach Feuer — before the latest wave had appeared on the field. In the last three years, in fact, a series of new spaces has been appearing in Manhattan, some of which are attracting the interest of collectors and the general public. What is remarkable is the cultural and attitudinal differences between this new wave and the one that preceded it.

Compared to the previous generation of gallery-owners, this new one is notable for its imaginative approach to curating and presenting art. There is less of a concern with pure market forces and a substantial openness toward an experimental approach underlined by a greater willingness to leave Chelsea and seek out less pricy locations. Some people still choose to stay in Chelsea for the visibility and the prestige it provides, but many others are setting up shop elsewhere, often in neighborhoods with no traditional connection to contemporary art. New Yorkers now seem willing to experience art in contexts other than the classic ‘white cube’ gallery: there is a great vogue for spaces such former shops, private apartments, and basements.

These galleries do not seem to be aiming to define a personal aesthetic or a particular taste, as was the case with Daniel Reich and John Connelly, but rather appear to be open to different experiences and experiments. They are often experienced as a meeting ground, a place to come together and exchange ideas. The attitude is less personalized and less glamour-oriented than it has been in the recent past. Group works, and collaborations between different artists are often seen. This greater spontaneity and the tendency toward group works do not however undercut the professionalism or businesslike attitude of these galleries. All of the gallery-owners I discuss in this article know perfectly well that a high price is paid for errors in the art world, and that it is important to be creative and also to have one’s feet on the ground. Even the most alternative spaces consider fairs like NADA in Miami, MACO in Mexico City, and Liste in Basel to be extremely important opportunities not only to sell works but also to build alliances and consolidate their position.

The Lower East Side and Chinatown

One of the most radical examples of this new tendency toward group activities is surely Orchard, founded in April 2005 by several artists (including Andrea Fraser, Gareth James and Christian Philip-Müller), an art historian (Rhea Anastas) a cinematographer and artist (Jeff Preiss), and a computer programmer (John Yancy Jr.). It is a kind of ‘joint-stock company,’ with a somewhat unusual approach to business. Each partner pays a monthly quota to underwrite exhibitions, and then the earnings from the sales of artwork are reinvested and eventually divided. Even though this is a money-making operation, Orchard makes an attempt to follow a path that is different from that of the other galleries in New York. For example, it does not represent any particular artist, does not usually organize one-man shows, and does not present itself as a launching-ground for young artists seeking fame and fortune. The shows are almost all collective, intergenerational and thematic, often with a very sophisticated art-historical approach. Their idea is to create a reaction, through specific cultural projects, not only to the laws of the market — which the group defines as ‘alienating’ — but also to the conservative political and cultural climate of the country. Their programming ranges from conceptual art to minimalism, from performance art to experimental film. One of their recent shows (curated by Jason Simon), entitled “Last Minute,” was a collection of one-minute-long videos from the first two editions of the “One-Minute Film & Video Festival,” (which was founded by Simon). Their show “Painters Without Paintings and Paintings Without Painters,” curated by Gareth James, presented two-dimensional works by Simon Bedwell, Daniel Buren, Nicolás Guagnini, Jutta Koether, Lucy McKenzie, Reena Spaulings, Cheyney Thompson, and others.

The Lower East Side, currently the city’s trendiest neighborhood, is the stomping ground of New York’s heretics and freaks. Four years ago, galleries like Canada, Rivington Arms, Participant Inc, and the non-profit Cuchifritos (located inside a supermarket on Essex Street) laid the cultural groundwork for these more recent efforts. In January 2004, Reena Spaulings Fine Art opened on the boundary between the Lower East Side and China Town; it has since become one of the strangest and most talked-about exhibition spaces. In order to obtain a Visa, the Norwegian artist Emily Sundblad had the idea to open a commercial space on the ground floor of a building on Grand Street. Almost by chance, with the help of the art critic John Kelsey, Sundblad began organizing events and performances. The gallery’s leading artists include Jutta Koether — also a member of Bernadette Corporation — Josh Smith and Klara Liden.

Recent Arrivals

Also on the Lower East Side, in October 2005 Thrust Projects held its first show. The gallery opened on Bowery Street, the same street that will soon be the new home of the New Museum of Contemporary Art. According to the gallery’s owner, and art historian, Jane Kim, the New Museum will inevitably alter the cultural landscape of the Lower East Side. The gallery opened with a solo show of work by Malachi Farrell, whose installation was bought by Paris’ Centre Pompidou. Other artists represented by the gallery include Jelena Tomasevic and Elizabeth Cooper.

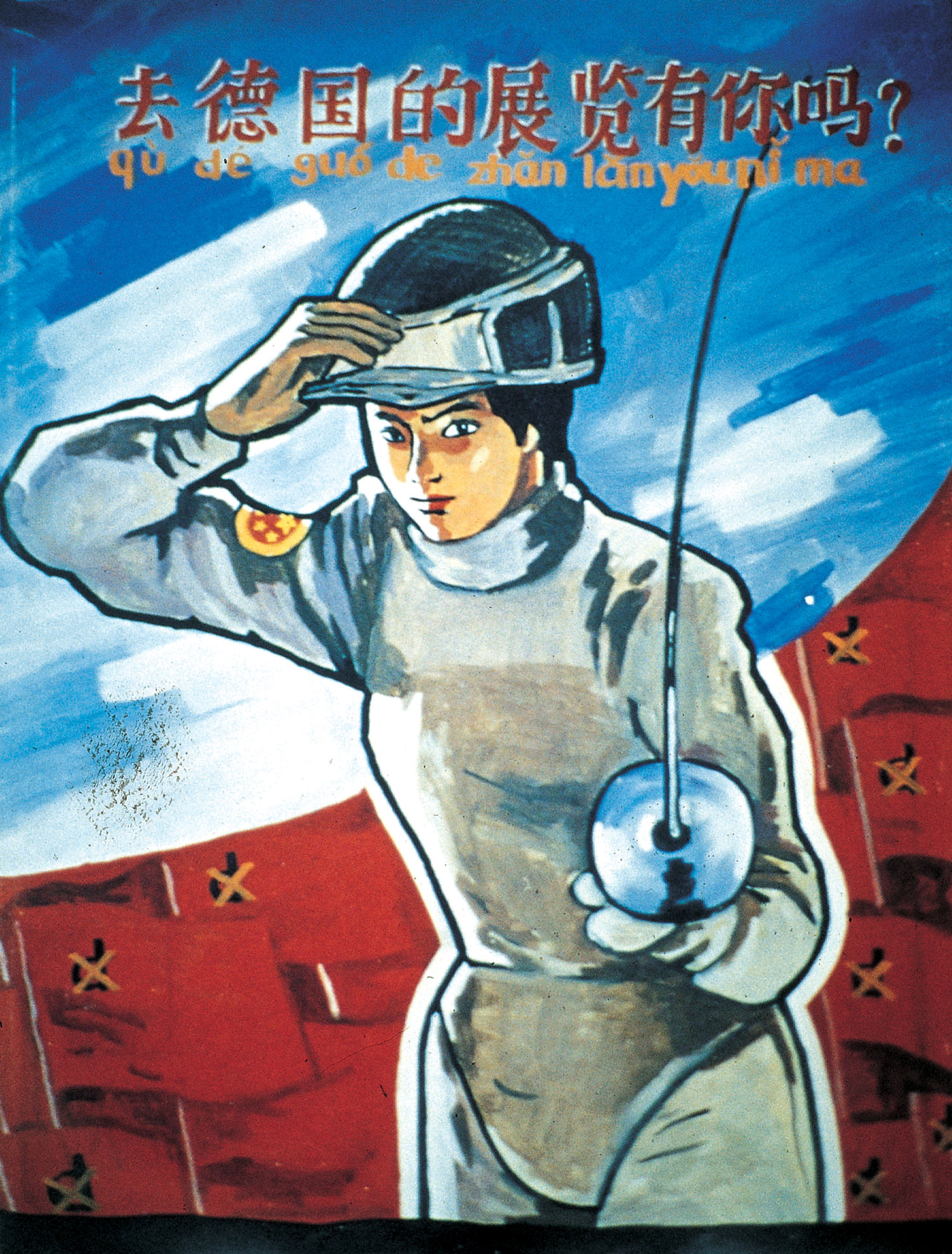

In March 2006, the Los Angeles gallery-owner Javier Peres, in partnership with the artist Terence Koh, opened Asian Song Society on Allen Street. ‘ASS’ gallery, as it is known in New York, intends to show works by Asian artists, or “artists who intend to take an Asian name, even if they are not Asian,” as Peres says. Peres and Koh are not planning a traditional gallery, but rather a space in which they can present projects that are playful and situational. In June, ASS presents a performance and sculpture by artist Zhang Zyi, who seems to be the umpteenth fictional artist to have been born in the Lower East Side in recent times.

Everything and its opposite seems to be the rule in this neighborhood. The Miguel Abreu Gallery, which also opened in March 2006, is much less playful than ASS, and seems instead to be characterized by a certain theoretical and intellectual attitude. For its first show, Miguel Abreu offered two films by the legendary Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet. Next month the gallery has organized a reading of Torpor, the latest book by the feminist intellectual and filmmaker Chris Kraus, originally from New Zealand.

Chelsea Redux

Other galleries chose to stay in Chelsea, which will doubtlessly continue to be the epicenter of contemporary art in New York for some time. Rents are prohibitive, so generally galleries start out with small spaces, often above street-level, and eventually move to bigger spaces when things go well. In September 2003, for example, Kelly Taxter and Pascal Spengemann began to organize shows in Taxter’s small apartment on 22nd Street. The following year they rented a larger space nearby, in a short period of time becoming one of the most interesting new galleries in Chelsea. Taxter and Spengemann met at Bard College, just outside New York, and decided one day at lunch to open their own space. Taxter & Spengemann does not reveal a particular line, but it does tend to show sculpture. Among the most interesting artists presented by the gallery are Macrae Semans, Charlotte Becket, Frank Benson, Matt Johnson, Daniel Lefcourt and Kalup Linzy.

In October 2004, Samantha Tsao and Angela Kotinkaduwa (who for a while worked for Michelle Maccarone) also opened a gallery in Chelsea, but unlike Taxter & Spengemann, they started off in a large space on 23rd Street. Both came from non-profit organizations like Thread Waxing Space in New York and Power Plant in Toronto, and they immediately started a courageous program, which has won them the support of collectors like Tim Nye, Rosa de la Cruz, Maja Hoffmann and Diane Ackerman. Among the most fashionable artists represented by Haswellediger — the name of their gallery — are Bozidar Brazda, Pia Dehne and Lindsay Brant. The gallery also presents the work of a luminary in the world of California art, Richard Jackson. Like other galleries from this generation, Haswellediger is characterized by a certain dose of spontaneity, revealed in a greater openness toward alternative projects. For example, in early 2005 they put together the first solo show by Reena Spaulings.

Janine Foeller, from Wallspace Gallery, started out with a space dedicated to emerging photographers, and later opened a larger gallery with Jane Hait in 2003. At first, they chose a second-floor space on 27th Street, and in January 2006 they moved to a gallery space on the street. Not surprisingly, given Foeller’s background, Wallspace focuses on photography as a self-reflexive medium, exploring its dialogues with other media like performance, sculpture, painting, video and film. Wallspace presents works that are characterized by a certain sensibility toward political and social engagement, though not in a systematic or programmatic way. Some of the gallery’s leading artists include Walead Beshty, Shannon Ebner and Helen Verhoeven.

Around Town

Michael Lieberman and Jessie Harris, who are married, met seven years ago when they were both working at Gagosian. After directing galleries — Lieberman was at Lombard-Freid and Harris was at Friedrich Petzel — they opened Harris Lieberman located on Vandam Street in September 2005. In their opinion Chelsea is still a great neighborhood for the older galleries, but for young gallery-owners it is almost impossible to find an interesting space that is not ridiculously expensive. For this reason they decided to open their gallery in one of the last unnamed neighborhoods in the city, an industrial area south of the West Village, north of Tribeca and west of SoHo. The first person to move into this area a few years ago was Gavin Brown, and now it seems that other galleries, like Michelle Maccarone, are planning to move to these parts. In the year and a half since opening, Harris Lieberman has become a must-see. Many of their artists are participating in important international shows, including Aaron Young and Ohad Meroni, both of whom are in the show “Uncertain States of America.” Matt Saunders, Stef Driesen, Michael Queenland, Daniel Guzman, Evan Holloway and Thomas Zipp have also received much attention of late.

Some are even returning to SoHo, a neighborhood abandoned by galleries under the pressure of real estate speculation as far back as the ’70s. In September 2003, Guild & Greyshkul — founded by three young artists, Anya Kielar, Sara VanDerBeek and Johannes VanDerBeek — opened at 22 Wooster St. In January 2005 the gallery moved to a larger space at 28 Wooster, next door to Jeffrey Deitch. At the start, the three artists/curators showed their friends’ work, gradually opening the gallery to a new generation of artists. Guild & Greyshkul meanders from the figurative paintings of Benjamin Degan and Devin Leonardi to the geometric abstractions of Garth Weiser, and from the neo-pop installations of Halsey Rodman to the surreal, apocalyptic sculptures of Johannes VanDerBeek. Guild & Greyshkul put a particular emphasis on their curatorial projects. Last year, seven of their artists were invited to participate in the show “Greater New York” at P.S.1: Anna Conway, Benjamin Degen, Ernesto Caivano, Garth Weiser, Lisi Raskin, Trenton Duerksen and Valerie Hegarty.

The art critic and independent curator Anke Kempkes is perhaps the only gallery-owner of this generation to open a space on her own, without a partner. Before landing in New York, Kempkes worked as a correspondent in Berlin for Frieze, and later as a curator at the Basel Kunsthalle. In July 2005 she opened her gallery, Broadway 1602, in an apartment in the Garment District, in midtown. An editor friend of hers rented her his apartment on the sixteenth floor of a skyscraper on 28th Street. Even if the gallery is somewhat off the beaten track, this location offers a particular charm: a view of the city and the skyscrapers of midtown, which imbues the space with a special ’30s New York feel. The nine artists that Kempkes works with are all European and come from the urban centers that she considers the most interesting at the moment on the old continent: Warsaw, Glasgow, Berlin and London. Among the most promising artists connected to Broadway 1602 are Ryan Doolan and Agnieszka Brzezanska, who took part in last year’s Turin Triennial. Kempkes intends to work with artists from several generations. At the end of the year she will present a show of Marc Camille Chaimowicz’ work, which she believes has influenced many young artists. This artist, who has been working since the sixties, was recently the subject of a large retrospective at the Migros Museum in Zurich.