It’s easy to be led to the abyss. — Cixin Liu

Catalina Ouyang sees their multimedia practice — an amalgam of object making, video, installation, performance, and collaboration — as above all an engagement with materials, ideas, and stories. When I first encountered their work on Instagram I was drawn to its complex, mysterious, layered symbolism, and the way it conjured a mythic, abject body rife with associations yet obdurately unknowable. Their contribution to one of the best group exhibitions I saw in 2021, “In Practice: You may go, but this will bring you back” at SculptureCenter in Queens, New York, cemented my obsession.

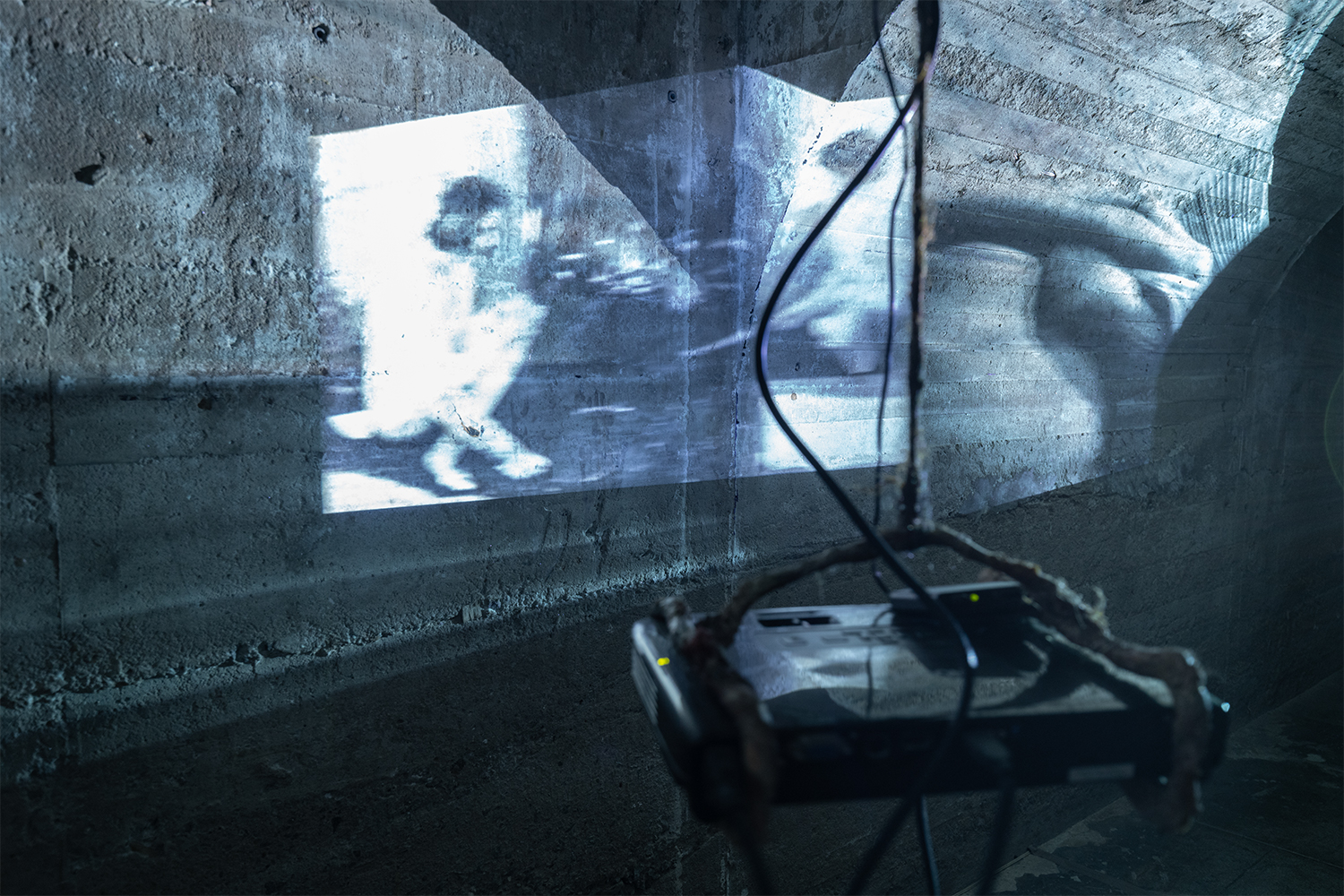

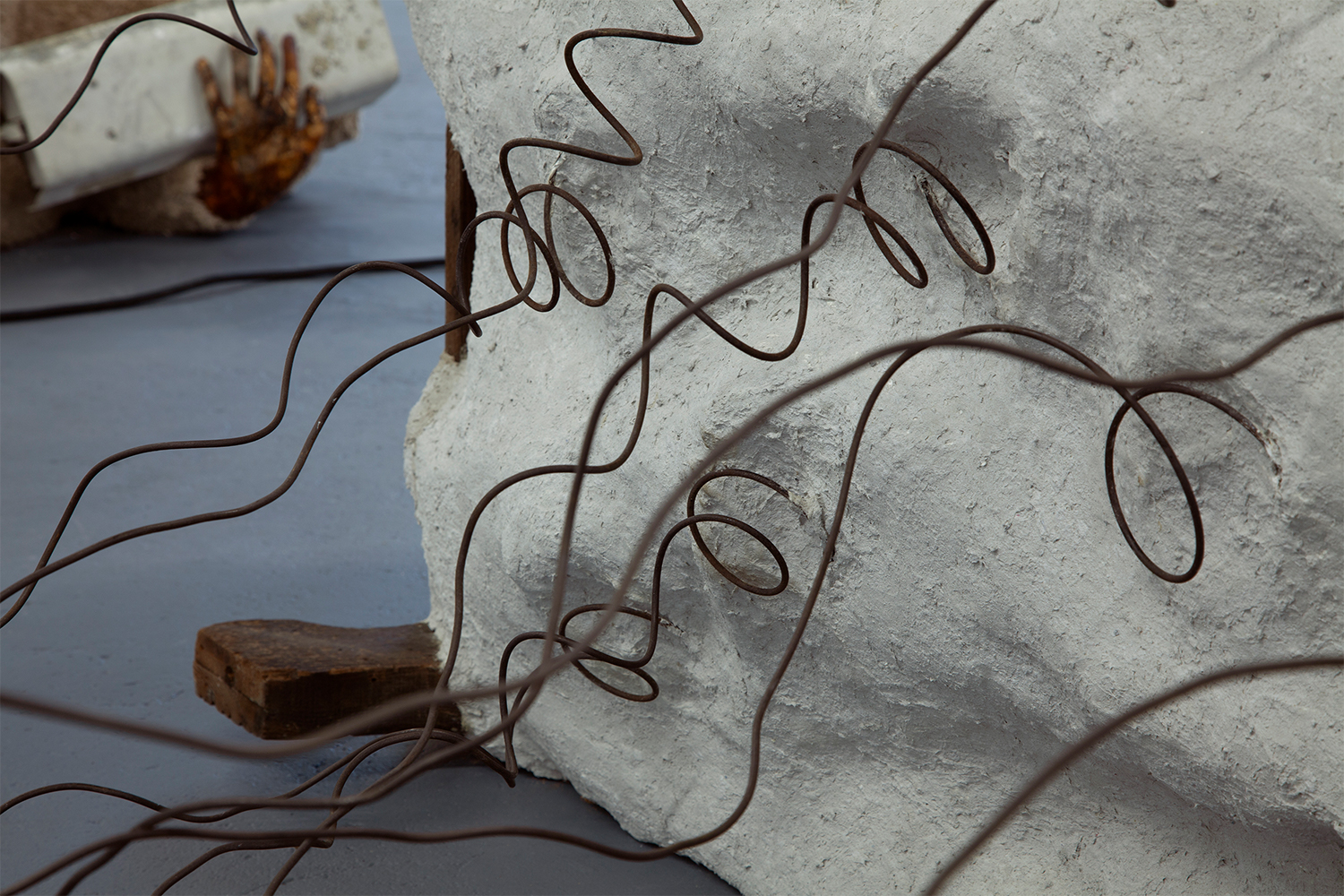

Brilliantly curated by Katherine Simóne Reynolds, the show explored “the notion of non- resolution through the lens of loss, grief, and mortality” (as per the press release) and was installed in the gallery’s basement space. Ouyang’s installation, common burn (2020–21), seemed as if it were unearthed whole from its catacomb-esque environs by a shaman-cum-archeologist. The figural carved wood sculpture reliquary janus (2021), in particular, evoked an antediluvian fetish, its gnarled humanoid form suspended upside down from the low curved brick ceiling like an unholy offering. Hung by a deconstructed fur trap (a medieval-looking instrument tantamount to torture), its marred surface of plaster, horsehair, polymer clay, and acrylic was punctuated by the bleached-white skull of a gray wolf. Nearby, a dangling video monitor projected altered black- and-white footage from La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928, Carl Theodor Dreyer) and Le lit de la vierge (1969, Philippe Garrel) onto an adjacent wall. The degraded patina of these films, with their subtext of subjugation and desire, merged with audio coming from a well in the floor. Therein, the disembodied voices of the artist and their mother could be heard reading and discussing two works by the contemporary poet Anne Boyer: “No” and “what resembles the grave but isn’t” (both 2017).

Like so much of Ouyang’s work, the variety of materials and references employed in common burn allude to psychosexual and generational traumas that are not meant to be resolved but rather give rise to contingencies of being outside logic and morals. The artist’s relationship to language is much the same. Go to their website: you’ll find a string of thoughts and quotes sutured together and a bloody knife that acts as your cursor. Reflective of a promiscuous, deeply intuitive reader, these excerpts suggest the affective nature of language, what the artist deems its “energy and patina” that over time can “rub off on object making.”

Ouyang’s preternatural commitment to their material and narrative process is part of what makes it so compelling. In the work [Conclusion and Findings] (2017–21), for example, they took the results of an open call inviting people to “translate” a 2016 legal document exonerating their rapist, and broke it down, word by word. The amount of labor spent on this dissembling of forty thousand words into a four-hour loop, like the sound of the artist slapping themselves that punctuates each one, verges on the masochistic. But for Ouyang this translation of a translation reveals the abstract, duplicitous power inherent to words. The video monitors on which they play are embedded in two Victorian chaise lounges laid on their sides that have been transformed and abstracted by plaster and celluclay. To view them, one sits on the nineteen-foot bitch bench (2018), a hybrid sculpture- bench based on the Capitoline Wolf of Roman mythology, which undergoes its own translation – a fanged, grinning self-portrait, replete with multiple breasts and human hands and feet, that also lies on its side.

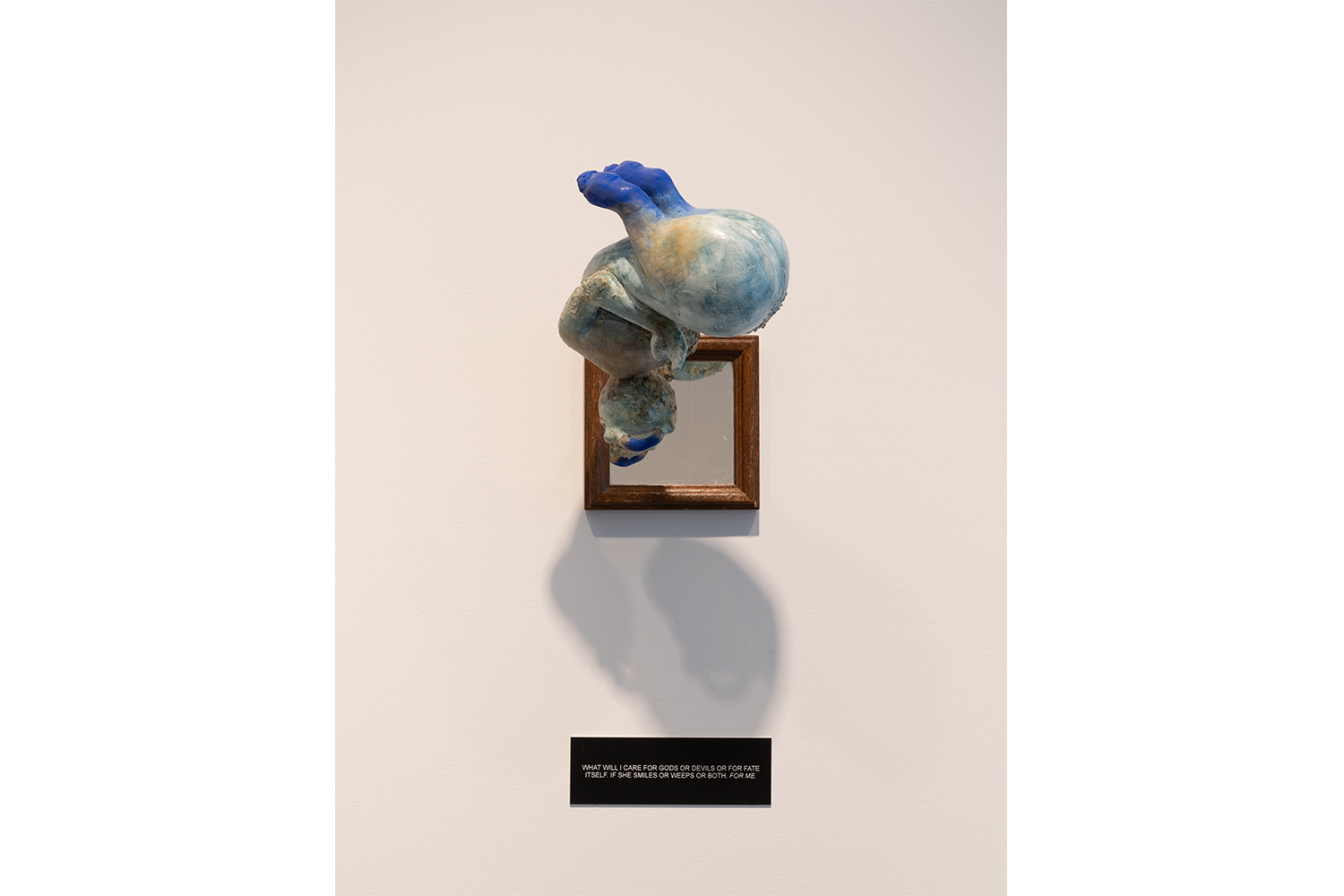

Ouyang often reprises older works, combining them with newer ones in another act of suturing. In their recent solo exhibition “White Male Ally,” in 2021 at Lyles & King, Devotion (2016–21) was shown alongside the installation ego death (2021). The latter recreated the squat toilet common in Asia, turning each stall into an intimate niche-stage for various sculptural vignettes. Nestled in one was font VIII (2021), a work from an ongoing series inspired by holy water vessels in Catholicism. Above its marble stone rendering of a human figure with a face on its stomach reaching into a shallow bowl (adapted from a seventeenth-century church), a vertical cascade of dried lotus roots attached to chainmail and a burned nightgown meet a pickled egg placed in the mouth of the stomach-face. A row of figurative sculptures, collectively titled Pronoun of Love (2021), lined the wall opposite, their inverted fetal forms attached with puppy skulls recalling reliquary janus. Each grotesquerie, back turned, gazed at its reflection in a mirror on the wall, and was paired with a quote from Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966). Highlighting the exhibition’s overarching themes of fidelity, loss, and faith, the Rhys excerpts derived from a specific passage in the novel in which the Creole protagonist’s English husband denounces her as a witch and a slut; her body, like her native land, once annexed, now forsaken.

Such themes also animate the artist’s current exhibition, “THREE BETRAYALS,” at No Place in Ohio, where once again the artist infuses their provocative tactile materialism with a heady mix of literary references — the works of Ann Sexton, Maxine Hong Kingston, Gilles Deleuze, and Cixin Liu, among them. Ever ambitious, it includes video, performance, sculpture, and drawing.

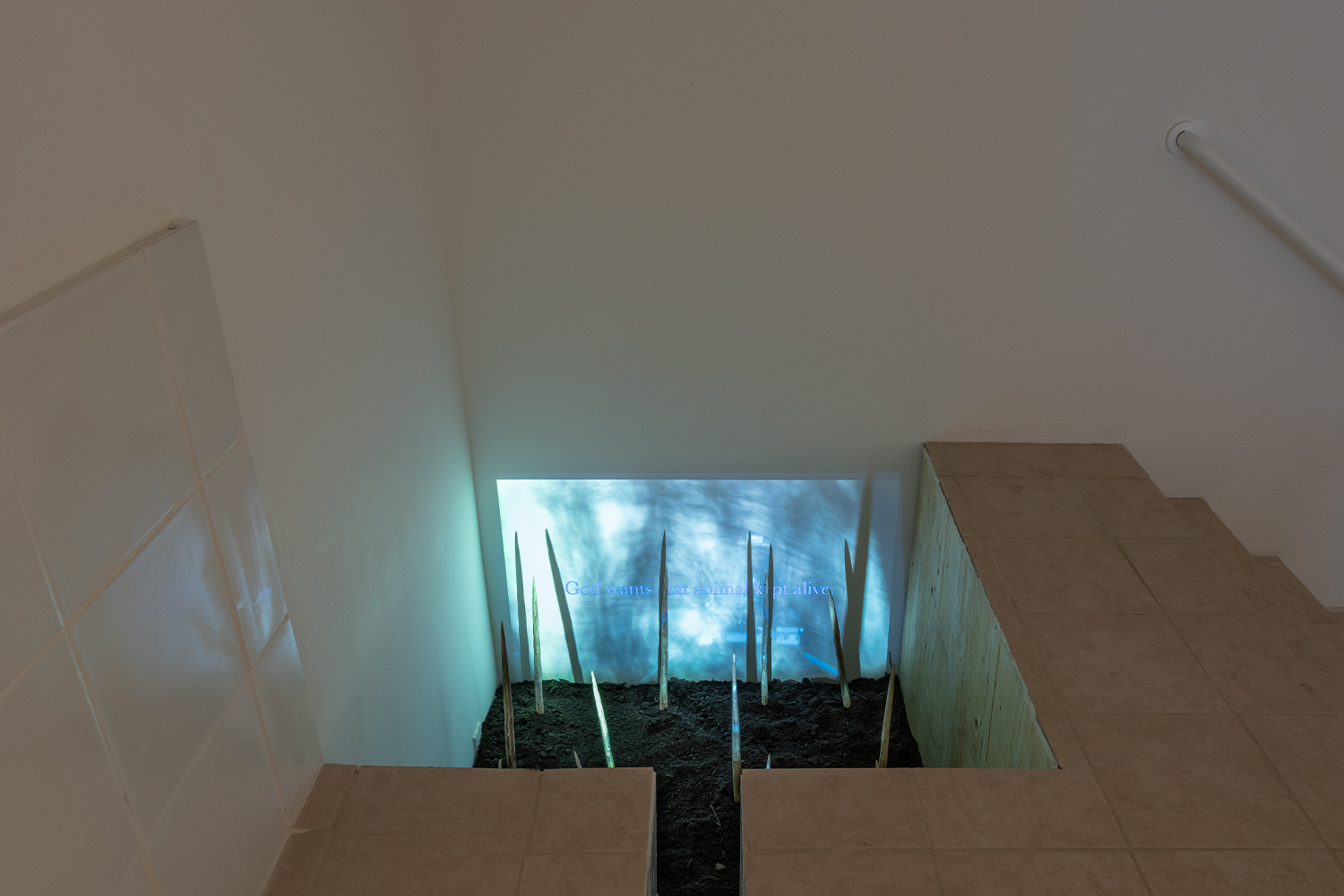

The eponymous video marks Ouyang’s forays into choreography, and depicts three dancers whose movements are intercut with various texts and footage (found and created) in an eerie dreamscape full of lingering affect. The figures turn and roll in unison on the floor, their flower-like triadic gestures obliquely simulating solutions to the three-body problem of quantum physics. Phrases such as “You must not tell anyone what I’m about to tell you” and screengrabs of phone texts — “did grandma do the secret procedures at people’s homes” — allude to underground abortions performed by Ouyang’s grandmother in her native China.

In classic Ouyang fashion, one story merges with another: biographical fragments conjoined with quotes from Kingston’s “No Name Woman,” the first chapter of The Woman Warrior (1975), about an aunt shamed for having a baby out of wedlock; Deleuze’s essay The Fold, which reconceives notions of the Baroque; and the biblical tale of a dog tied to a mandrake plant who dies after pulling out the poisonous root. Vernacular videos from films highlighting mother-daughter exchanges are interspersed as well in this exquisite corpse of generational trauma that unfurls with the hallucinatory wisdom of an ancestor-heretic.

Expressive ballpoint pen drawings of Anne Sexton that render the confessional poet as alternately unhinged and transcendent add to this ecstatic feeling. So too does the sculptural work Scorn of God (Quinn), 2022, which, reminiscent of the dancers, lies prone on the gallery floor. The one-legged carved wood form is enveloped by a stream of blood-red fabric tentacles, its half-human, half-plant form fanning out from a black pleated schoolgirl skirt that covers the figure’s head: “In many myths around the world, it is important to conceal your true name or identity because with your true name, other beings—possibly malevolent ones— have full control over you,” Ouyang shares. “I think about this in relation to dismantling or rejecting an expectation of performing and upholding any one identitarian position.”

This secretive protective impulse is a wellspring in Ouyang’s practice for subterranean, generative, and alchemical visions of the unruly, mythic body that are at once taboo and revelatory. Through a gnostic brew of associations that never quite cohere, their work reminds us of the limits of language and hegemonic knowledge, leading us to the bewitching edges of a feral imagination.