The video starts off simply enough: teen or pre-teen skaters of modest ability fly through a sunny, suburban context. They document middling kick flips over low curbs with a handheld camcorder and an extra-wide-angle lens. The teens’ off-camera voices don’t reveal any particularly distinct geographic locale besides North American. Not thirty seconds into the ride, the skaters are interrupted by a panicked women. She rushes them, pleading for help in a strong Eastern European accent. As she accosts one of the skaters, he jumps off his board and she quickly kneels to grab it. The woman then turns and takes off, yelling for the kids to follow. The scene takes us to a nearby parking lot, where the women’s two young children, between one and two years of age, are trapped inside a minivan. She and her husband beg the skaters to break the windows of the car so that the toddlers may be freed. The boys try.

The video, a work by the young artist Bradley Kronz (b. 1986, American; lives in New York), was presented at Team Gallery’s new exhibition site in Los Angeles earlier this year. There, the humdrum but briefly tense narrative of the piece was projected and looped. Its main, uncut video segment was found online by the artist. Rather than manipulate the footage, Kronz decided to present it unedited, only adding a brief abstract animation at the very end of the piece. From a series of digitally rendered inter-titles before this bookending abstraction, we learn that the source material dates back to 2010. So why does the work look so ’90s? Maybe it’s the grain and colors of the interlaced stream, which suggests a MiniDV or similar camcorder in use. Maybe it’s the fisheye lens. Or, perhaps it’s the genre of the thing itself: kids who skate recording their exploits, imitating a style of skate video formalized in the ’80s and widely popularized in the early ’90s — a time when such tapes could only be found in neighborhood skate shops and mail-order catalogs. The skate video genre is one whose stability was put into flux since the emergence of YouTube and other video-sharing services, as well as the general democratization of video recording technology via even the most modest of smart phones. In this regard, Kronz’s own video seems a bit historically adrift. It’s out of register with the time of the source material: this “found footage” is neither historical nor exactly contemporary. Rather, one could describe it as a rapidly aging piece of media, lacking the advanced software-enhanced clarity of an iPhone video clip. It lays out its narrative against a cloyingly saturated video-blue sky and a contrived wide-angle view.

The way this particular work traffics its formal payload of found footage brings to mind the ways in which Martha Rosler has written about the discarded commodity. “Not old enough to evoke nostalgia, only shame,” the cast-off commodity, according to Rosler, is an artifact of culture that belongs to the just-past, seemingly awkward and out of place in the context of the present. This is a period in the commodity’s life before it can be considered vintage or once again desirable, a metonym for an entirely different era or symbolic regime. This is the culture of our parents, the clothes we were wearing five (rather than ten) years ago, our discarded ambitions and ideals: all things that are uncomfortable to think about from the perspective of the present. The kids in Kronz’s piece originally set out to make a skate video and failed. There is little skating in what they’ve produced. Their failure, however, is perhaps not so incongruent with the artist’s own. Rather than making aggressive cuts or perplexing juxtapositions as a generational predecessor may have done (think of Rosler or Elaine Sturtevant), Kronz simply footnotes the found footage with a touch of abstraction. Let’s take this as an entry point to thinking about some of the other works Kronz has produced over the past two years.

In his summer 2014 exhibition “The Ambitions of Large and Small Things” at the gallery Off Vendome in Düsseldorf, Kronz presented an untitled set of two related (but individual) paintings, both depicting red hands in subtle gestures against a bright, out-of-view spotlight. The hands cast shadow puppets in the light: silhouettes of a dog and a hare. These paintings, hung only inches apart, actually originate from a single, found canvas Kronz rescued from a trash bin at one of his several short-term studio sublets. To make it his own, Kronz split the painting in half, literally cutting it, and in the process serialized an otherwise monolithic work — not unlike the way so many painters today serialize their working methods to create unique but highly reproducible bodies of work. For Kronz, the body already reaches its reproductive limits at two. Thus, an unloved painting begins a second life as a duality: freed from its stretcher bars and inserted into the paper stock frames for which Kronz has become known.

What happens when a painting begins a second life in Kronz’s frames? The artist has cautiously deployed this strategy in other works, over the course of several exhibitions, in turn beginning to work as a painter. The first thing that happens is a general slackening. A painting in some sense is defined by its tautness, whether it is stretched across bars or simply a panel or board. Kronz’s shadow-puppet painting in this regard is now suddenly lankier, hanging more loosely, malleable. Like a muscular, disciplined body suddenly made limber with a stretching regimen, the painting seems larger in subtle ways. Bits of canvas previously confined to the back of the stretcher bars are now visible near the edges of the artist’s frame. Secondly, a sort of inherent naturalism returns to the painting’s substrate, which rolls and moves, ever so slightly, as it comes to inhabit its new dwelling.

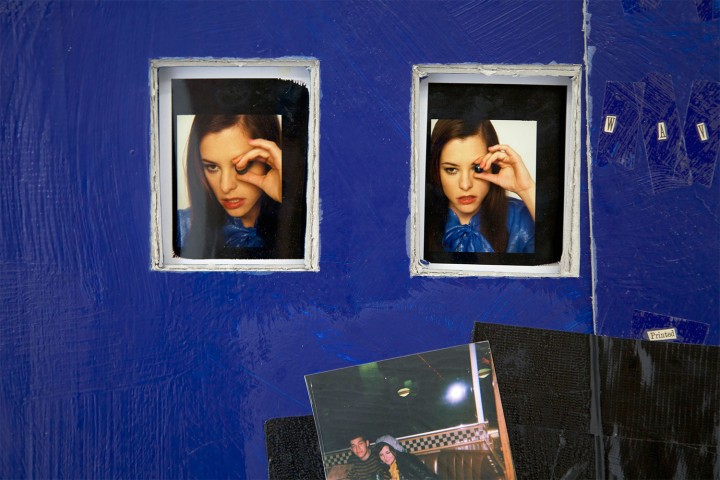

Kronz’s paper frames are tricky constructions. Encountered in digital images on the Internet, they’re easy to miss. They don’t attract the eye nearly as much as his hand-rendered drawings or the photographs and paintings Kronz appropriates to make his own. The frames are often quite thin in relation to the work they encase. They also rarely contrast or make a visual fuss with their tenant works. Sometimes they aren’t picture frames at all, but rather the ground upon which he arranges and manipulates one or more found photographs. Unlike their professional counterparts, these frames don’t profess an overwhelming concern with presentation. In this sense they operate with a modicum of stealth, but they don’t exactly seek to disappear. On the contrary, like a shy but eccentric party guest, they become hard to ignore after they are noticed. They often show up in exhibitions disheveled and scratched-up, occasionally cracking at the edges. They might be made of cardstock of various types or very high-end watercolor paper. Others are constructed from repurposed, ready-made cardboard framing stock, often left unfolded or otherwise deconstructed. Some are just sloppy, one might even say.

If professional frames buttress an aura of value, desire or status in an art object, Kronz’s frames exhibit something much more fugitive: they exhibit a kind of naïve care on the part of the artist. Consider his 2013 exhibition “JUD” at New York’s Essex Street gallery. There, a series of drawings, photographs and sculptural compositions were presented by the artist, many of them in custom cardstock frames. In one wall-bound work, Moms 280C (2013), two photographs from the artist’s family archive are playfully pinned to an unconstructed paper frame kit the artist uses as the ground for the composition. The images he chose to present in this work are the kind of photos that would be awkward in a family album. These are unpeopled images: there are no grinning family members, views of an exotic vacation locale, no toddlers posing with grandparents. There is no family gathering or important ceremony being depicted in these pictures. Rather, there are simply two nearly identical photographs of a car in the process of being painted. It calls to mind the kind of vanity portrait a young man might take of his first automobile, souped-up or freshly painted — functioning not unlike a second girlfriend, an extension of the male ego, a kind of symbolic phallus. But it’s hardly a vainglorious moment for the vehicle in Kronz’s work. Missing a bumper and half-painted, the Mercedes in the image — a low-end Mercedes in an American garage, already a powerful aspirational symbol — is presented as a kind of vulnerable, naked commodity. It’s a commodity stripped of its prestige and further cheapened by a visual doubling. Unlike other works in the show, the edges of the photographs are not covered by framing material. Instead, the pictures are presented bare.

In another work from the same exhibition, Jeep (2013), we see a swiftly dashed-off marker drawing approximating a photograph. The image, somewhat abstracted by the tight cropping of its subject matter, is an image of vacancy: the traces of a dislodged Jeep car logo, the American brand of capable masculinity, occupies the center of the image like a ghost. A drawing inspired by another sort of reject-image from a family album, Kronz entombs it in an off-white cardstock frame. The result is sort of funny. Rather than protecting the already stained paper from the exposure of UV light or physical trauma, Kronz’s frame offers us instead the artist’s twee affirmation that this image is cared for. In place of a caption, a narrative or a relationship, we have only this vacant, ineffective promise. Dad’s jeep? A healthy brand logo is already something that, when it works, evokes sentiment as much as it encourages us to pour our own sentiment into it. As such, every logo and every commodity envies the family heirloom. Commodities that serve us longer and with more intimate contact and purpose — like a car, for instance, in which one experiences many emotions over many years of ownership — often create deeper and more intimate bonds with their possessors. Kronz often presents us with work that is materially insignificant; that is, made from inexpensive or discarded material. But through operations of framing, presentation and doubling, he creates what appears to be a kind of auratic context of care and importance between himself and these objects. The work is strongest, however, at the moment of the outsider’s confrontation with it. Imagine coming face-to-face with Kronz’s presentation of family photos or drawings in slapdash, homemade cardboard frames — works that explicitly mime counterparts in the world of commodities and personal media with the deliberately flatfooted affect of a theater prop. These objects will suddenly seem to mock us: how do we submit to the affective regime Kronz fabricates with such subtle process and downtrodden material? How to fall under the spell of something so foreign, so explicitly ineffective?

Writing about the Essex Street exhibition two years ago, I compared the works in it to coffins, which maybe they are. Coffins, after all, are vessels with which we affirm the sanctity of the human body after its animating forces have long withdrawn. Consider the logic of the artist’s custom frames. His is not a museological approach, seeking to preserve or isolate works of art from the natural world and the forces of time. Rather, his framing is more in the spirit of the kind of sentiment that proxies the affective energies we have for our loved ones onto family photos and their possessions, long after they have departed. It’s an uncertain and flighty kind of sentiment with which we stay connected to that which is now out of reach. It’s flimsy. Rather than affirming a triumph over time with technology, like the industry of personal media and photography seems to promise us, Kronz’s work suggests a response to time’s passing that is mournful, sweeter.