“The true artist must swear an oath: Dedication to silence”

– Federico Fellini, 8½

Cady Noland is a bona fide art-world outlaw — the last of her kind. She may also be our foremost post-gallery artist, one who seems content to exhibit in that most underground of all artistic venues, the mind. Self-exiled for more than a decade, Noland has earned her cool notoriety. Unlike many of her heat-seeking “bad-boy” contemporaries, she does not collaborate with Young Hollywood, decorate handbags, or act as guest judge for televised art contests. Her silence is a golden gift, a sanctuary from the art world’s constant need to generate buzz. Noland is the shadowed yin to Warhol’s spotlit yang, and together they perhaps best symbolize every artist’s inner struggle to balance artistic autonomy with market popularity. With access to Noland’s new work limited to hearsay a writer has little recourse but to interpret her absence (at least in part) as a loaded gesture, a dark extension of her equally dark early work, and to look for its relevance in today’s climate. So far, not even the small (albeit vocal) gang of critics who continue to champion her seem willing to comment on why Noland, their prodigal daughter, has shunned the art world, or if there is some artistic/political merit to her gesture.

For the record, I am not interested in deifying Cady Noland. There are others who have made this their work. Of particular note in this category is writer Brian Sholis, whose zine Why We Should Talk About Cady Noland postulates: “Perhaps she is stalling and will one day choose to exhibit her work. As we move further from the time of its creation and exhibition, and as her influence proliferates among a generation of young artists eager to plumb the underside of contemporary culture, it becomes increasingly important to not let her significant achievement slip from memory.” This lamentation, while clearly the product of a Noland fan-boy, not only denies the latent power of her silence but dismisses its topicality, its usefulness to the young artist. What better way to thwart the market than to deny it one’s art? What greener way to make art than to make none? How better to stand out in a sea of fame-seekers than to shipwreck oneself? Lessons like these can be gleaned from Noland’s silence. Lessons that at their core contain the same basic idea: relentless exponential growth is not the only career trajectory available to an artist — exponential shrinkage is equally valid. Sacrilege, I know.

“Attitudes,” to quote Harald Szeemann, “become form.” There are examples of this tenet at work throughout art history, with the splatter technique of Jackson Pollock being perhaps the most obvious. Noland hijacks the motto and edits it down. In the matrix of her silence, attitude is form. Which is perhaps only another way of saying that life always bleeds into art (and art usually back into life). Could Noland, whose career is a kind of caricature of her early muse Patty Hearst — the media heiress, turned cult member, turned recluse — be understood as the embodiment of this circuit (i.e. an artist who walks the walk)? For a brief time, before we became the makers of shiny baubles for the rich, artists were a part of the outlaw caste. Art was our weapon. Picture for a moment Gordon Matta-Clark. The year is 1972, and Matta-Clark, power saw in hand, is hacking apart the floor of a derelict building in the Bronx. Two police officers, suspicious of the noise, enter the building with weapons drawn. Matta-Clark manages to avoid arrest, or worse. It’s a far cry from the cozy, gallery-endorsed “interventions” we now celebrate as cutting-edge. Noland’s silence, like Matta-Clark’s anarchitecture, suggests that attitude and form must be kept at parity in order for art to thrive. Art without attitude is decoration.

There are parallels between Noland and my father — a musician who abandoned the music industry in the late ’70s — that reinforce my belief in the power of silence. The indie records that he and his brother produced, nearly lost to wherever it is that obscure Canadian garage records go to die, are proving to be surprisingly resilient, and presently enjoy a kind of cult status that’s evidenced by their radio play, a recent mention in Rolling Stone (alongside The Velvet Underground and The Beach Boys) and samples of their music on hipster recordings like that of Animal Collective’s Panda Bear. There is proof in this anecdote that good art finds longevity in unpredictable ways. Catering to the market is therefore not only potentially a shortsighted career move; it may also be the surest way to make inherently weak work. Admittedly, distancing oneself from the market may feel counterintuitive. Like career suicide. But with this ‘death’ also comes the freedom to create outside of the confines of a cultish art world.

I will be the first to admit that shit-talking the system from within the system is problematic. Magazines are a part of the art world hierarchy (and generate revenue in part from galleries and museums to boot). I would also like to concede that there are countless works of art, literature and music that would cease to exist were it not for the support of the system (or perhaps would cease to exist as we now know them). And in the spirit of transparency, I admit that I too have benefited from my gallery relationships (I even ran a small gallery in Chinatown for a short time). I would go so far as to suggest that the profession of art dealer is one less compromised than that of the artist. The art dealer has no qualms about commodifying art, and therefore works with a clear conscience. The artist fears both commercial failure as well as the loss of credibility that comes with having too much success, and therefore shifts back and forth between serving their vision and kowtowing to the demands of the market. That said, the artist in me still hopes that Noland will continue to challenge the system. Is her golden silence a suitable substitute for cold hard objects? It depends on whom you ask — those who are tantalized by the possibility of new work, or those who relish the gift of her silence. I am not advocating that every artist adopt her extreme attitude — this would be a poor fit for most. In fairness, some artists are at peace with their work and careers while others simply don’t have the luxury of biting the hand that feeds. Perhaps it comes to down to this one simple question: Warhol or Noland? The heat of fame or the cool of notoriety? Which should we pursue? Which makes for a better artist? I should probably shut up and find out.

Bozidar Brazda

It was March 1992 and the door to my graduation show at CalArts had recently been sealed by the local sheriffs. I had hauled machine guns and dynamite detonators into the school’s fluorescent-lit gallery, written chemical formulas for explosives on the walls and broken a hole in the ceiling. Fellow students had alerted the police, not realizing that what was on display were obviously just props or art works. It didn’t help that the centerpiece of the show was a video of a bank robbery that I had staged at the closest Wells Fargo bank. Despite the hiccups with the authorities, I still passed my final exam and hit the road with a couple of other students to move to New York. Once there, we found the city hot and deserted. I joined some friends at Documenta 9 in Kassel to assist with installing the artworks by the participating artists. The highlight was working on Cady Noland’s installations in the underground parking garage between Documenta’s main museums.

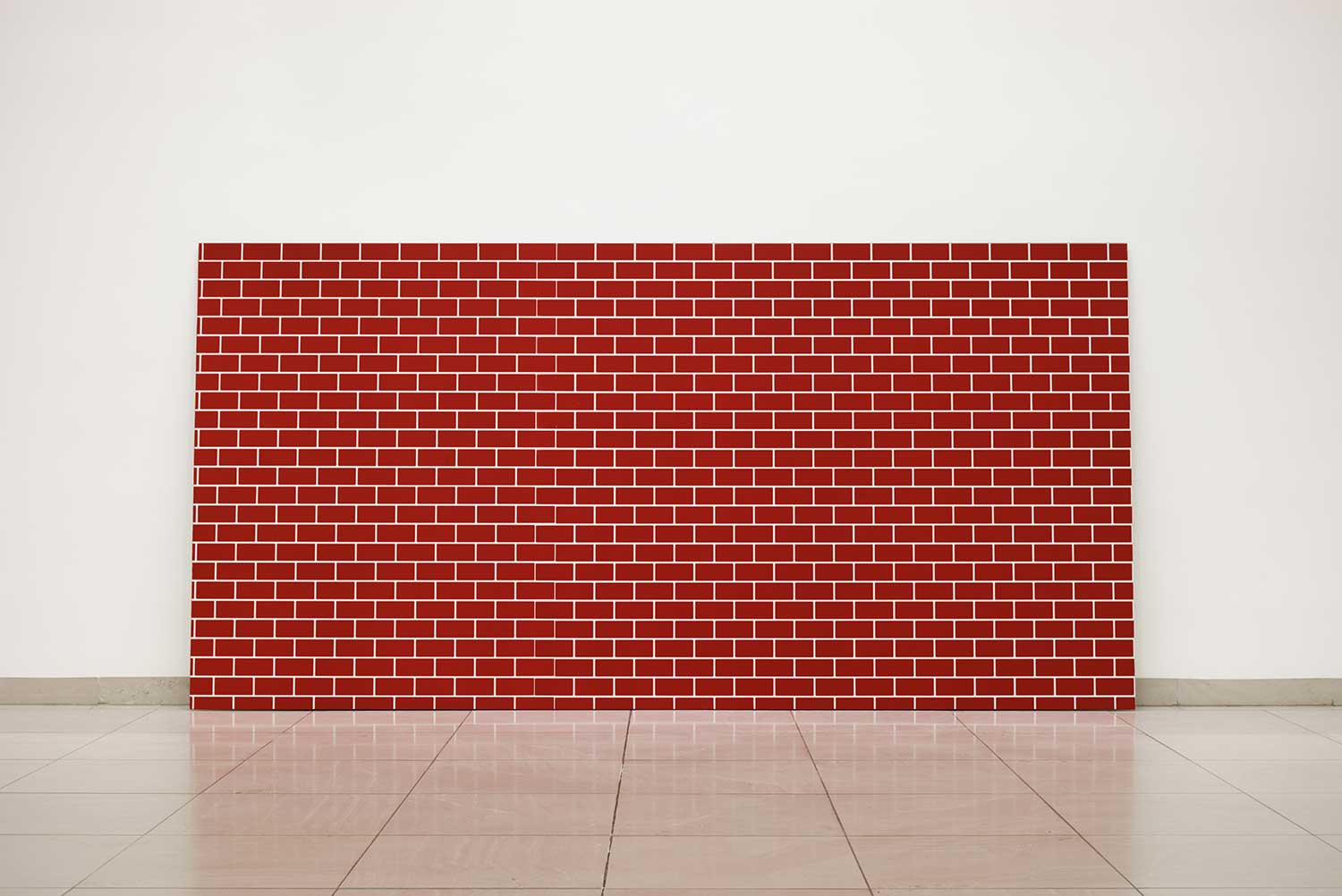

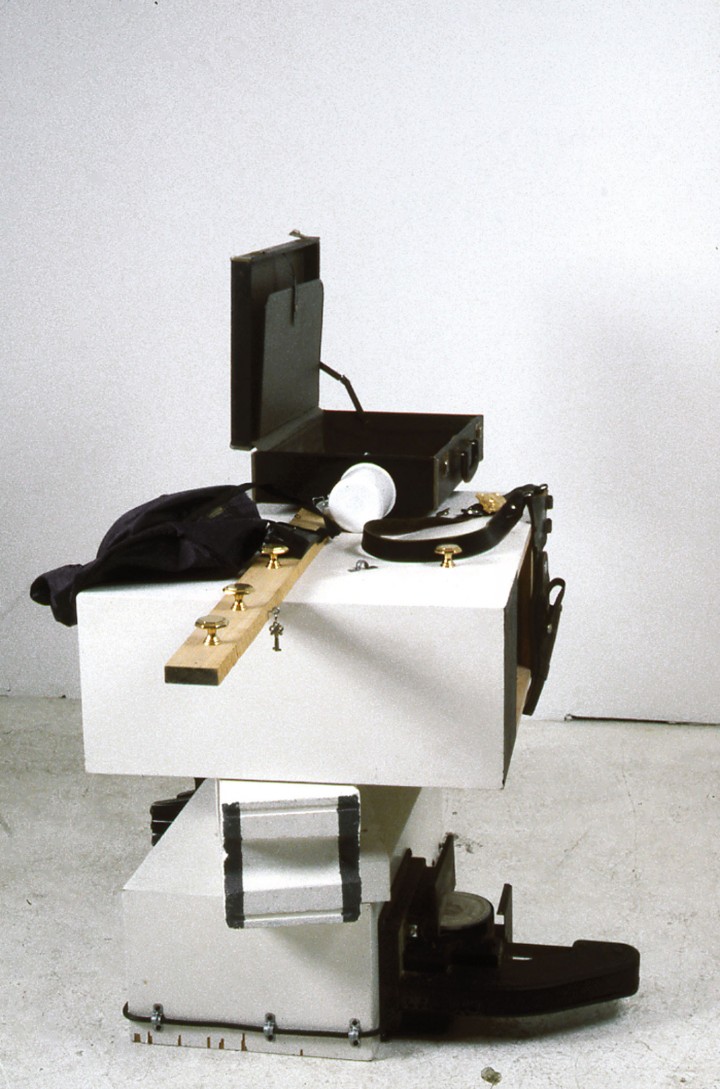

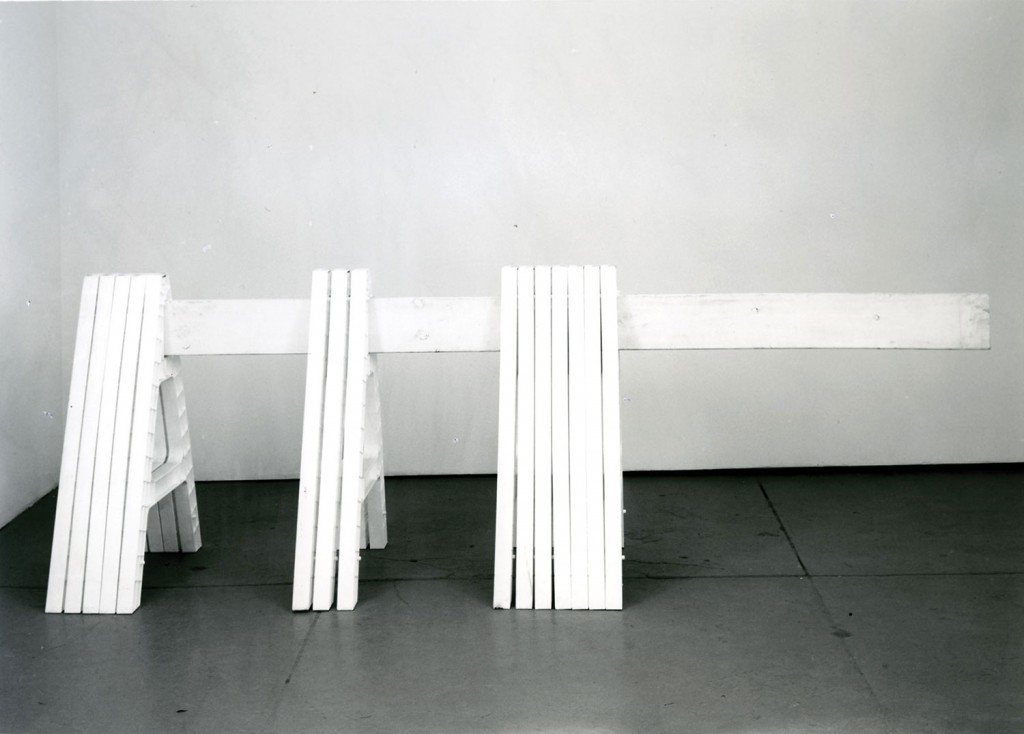

Cady had one of the biggest pieces in the exhibition, a sprawling installation spanning half the width of the garage, centered around aluminum text panels of her 1987 essay “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil” casually leaning against the cement walls. The car garage was still under construction, more a war zone than exhibition site. Cady had put heavy cinder blocks and safety tape in front of her installation with neon tubes behind the stones to light it. On view was a red vintage American Camaro alongside artworks by her friends such as Steven Parrino, puddles of oil and an unfinished Jessica Diamond wall painting. Next to the main installation was a large van turned on its side, front crushed in, glass windows shattered, sitting on wooden pallets. Danger and chaos lay in the air. We moved cinder blocks, metal barriers and art works around for several days in the cold, dark underground; no matter what we changed, the installation always looked good. The curator Jan Hoet and his team seemed slightly nervous about the very involved installation process that continued right up to the night before the opening, but were ecstatic about the end result. Cady’s piece ended up being one of the most exciting and talked about works in the exhibition.

After moving back to New York I went on to publish the first issue of FAT, a conceptual magazine project in tabloid disguise. The theme was “Good and Evil,” and included contributions by Ashley Bickerton, Jason Rhoades, Sam Durant and Sylvère Lotringer, among many others. I asked Cady to contribute but couldn’t convince her to participate. My work has metamorphosed drastically since then. While it has shifted from the magazine project to films, photography, display arrangements and shop windows, my working style of throwing things together quickly and then obsessing about the details towards the end is reminiscent of the days spent with Cady in the deep pit of a parking garage in Kassel.

Josephine Meckseper.

* * *

Despite, or probably because of her decision to not actively participate in the current discourse of visual art, Cady Noland has become a reference and a legend for at least two generations of artists. Traces of her “visual anger,” of her uncompromising criticism of American society, can be found in the form, content and especially attitude of the work of American artists Sam Durant, Matt Keegan, Rachel Harrison and Nate Lowman, who even made a work of art dedicated to Cady Noland; British artist Helen Marten; German-born and New York-based Josephine Meckseper; and Canadian-born but longtime New Yorker Bozidar Brazda. Not aiming to give an extensive overview of Cady Noland’s work, this editorial project was conceived as a means to generate new interest in the career and practice of an artist who has marked the history of American society through a direct but never obvious practice. Cady Noland leaves a body of work that still resonates as one of the unique voices in the contemporary art field and one of the strongest commentaries on an era that has seemingly come to an end.

Nicola Trezzi.