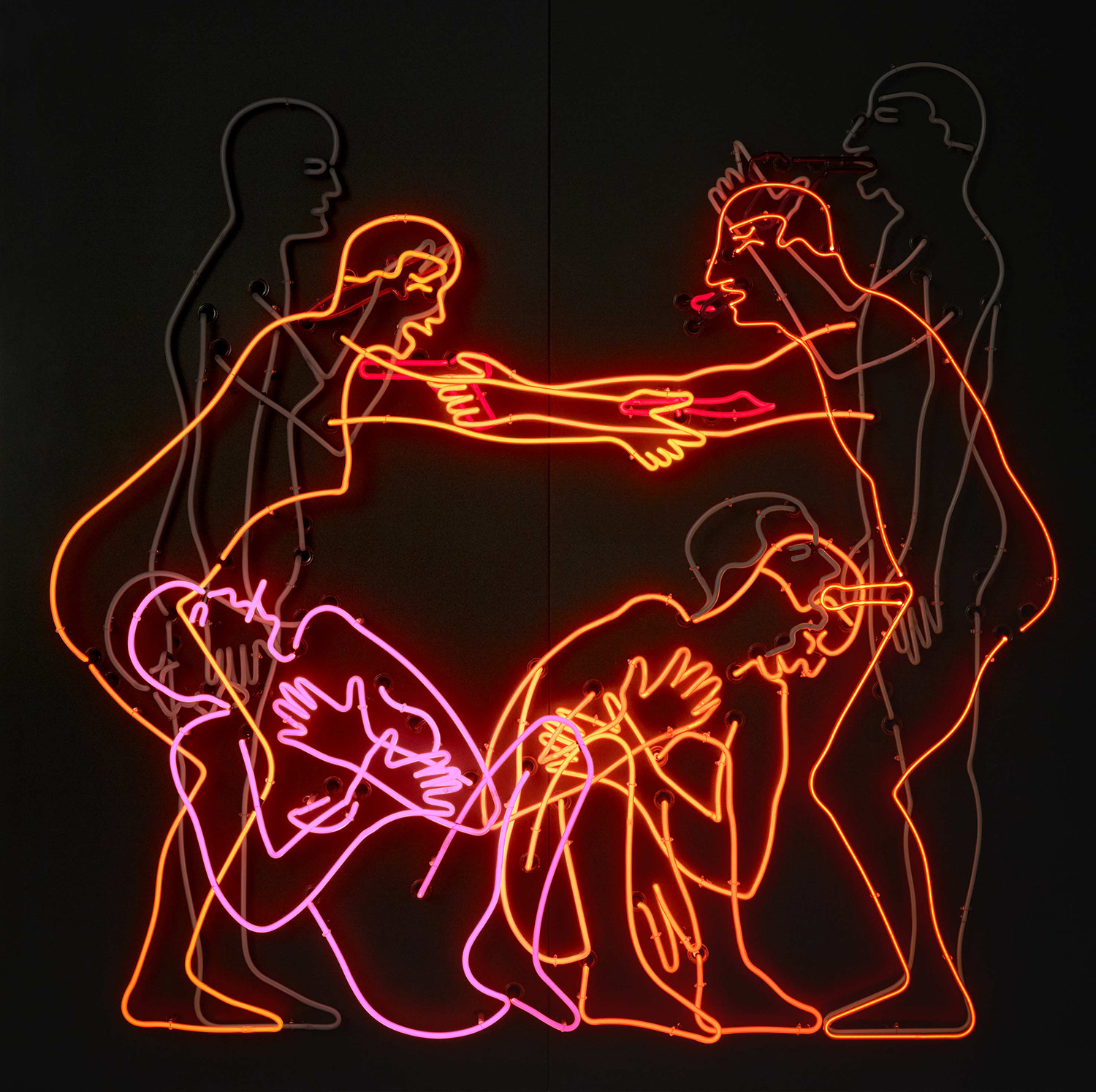

At the end of March, the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C., opened the exhibition “No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man.” The show, which is the museum’s physically largest install to date, filling not only all of its galleries but also extending to the surrounding neighborhood, is dedicated to the large-scale participatory sculptural and installation works the annual desert festival–cum–temporary experimental city is known for.

Installed indoors, away from their native setting — distributed across the vast expanses of the “Playa,” as the dried-up lake basin desert where Burning Man is held is affectionately known — the works take on a much more monumental character. Also, they beg the question of how this art should be judged in this new setting: Is it capital-A “Art”? Or does it exist in some kind of judgment-free register of awe outside the boring scope of “real art critique”? (As James Tarmy asserted in his review of the exhibition in Bloomberg, “Art made for Burning Man isn’t designed for judgment”[i]). What are we to make of, for example, Marco Cochrane’s six-meter-tall stainless-steel sculpture of a dancing, conventionally attractive nude woman titled Truth is Beauty, without recourse to the helpful category of kitsch?

And why this exhibition now, at an institution like the Smithsonian? It does seem we are living through peak Burning Man right now. Its cultural import has been hard to miss, even by those on a purely MSM-based information diet. The rise of Burning Man’s cultural cache corresponds with the rapid growth of its attendance. Black Rock City — as Burning Man’s temporary settlement is called — had a population of around 8,000 in 1996; twenty years later it was 70,000. This year the festival’s 75,000 tickets sold out within minutes — priced at 425 USD, more than ten times the 1996 price.

A major driver of Burning Man interest over the last five years or so has been the Silicon Valley-fication of the festival and what some see as the hostile takeover of its spirit by the 1%. In fact, this year the “theme” of the festival is “Artificial Intelligence,” which has led some to question whether Burning Man has in fact become a tech festival. In the words of Erik Davis, author of Techgnosis and longtime burner, “major money is getting freaky now.”

Looking at an important earlier Burning Man document, the photography of Leo Nash in his book Burning Man: Art in the Desert, published in 2007, documenting thirteen years of life and art on the Playa, it would’ve been hard to foretell its cultural ascendance. The crusty DIY aesthetics and material culture of a much more sparsely populated Black Rock City are a long way from the ornamental top hat and mirror-embellished vest worn over business casual attire by Google’s former CEO Eric Schmidt in 2016 or the fully serviced turnkey smart-yurt camps of today.

Why and how has Burning Man itself and the act of signaling membership to its ethos via a codified aesthetic concoction of steampunk tropes, offensively appropriated indigenous ceremonial attire, the psy-porn of visionary art, never-never land, and drop-crotch pants become aspirational?

Cue in the experience economy.

The following should be taken with a full cup of salt, but bear with me: the adjective “millennial” might be less useful as referring to membership of a specific age cohort than as shorthand for the phenomenon of experiencing one’s life chiefly as a narrative, with the self playing the lead role. In particular, experiencing one’s life as a “journey”: a meaningful if meandering path toward some form of authentic discovery and realization of the self. If you squint, it becomes clear that almost all popular conceptions of millennial traits can be attributed to this narrative foundation: narcissism, commitment issues, the obsession with wanderlust, magic, passion, and purpose. And these traits are by no means limited to those born in the ’80s or early ’90s: large swaths of Gen Xers and Xennials have come to narrativize their lives in a similar vein.

Within the framework of one’s journey, the primary unit of currency is an experience. And under the experience economy the most valuable form of capital is a transformational experience: a genuine refactoring of the perception of the self and the world around it, typically rooted in a profound experience of the oneness of being and/or limitless potential of the self (and rarely the suffering of others, injustice, inequality, etc. — vibe killers). The Burning Man ethos taps perfectly into this economy, providing all the necessary means for a transformational experience with an instantly recognizable aesthetic framework.

Over the last ten years, Burning Man has grown beyond an annual event into something akin to a cultural movement that has transcended the reach of the event itself. A budding industry has developed in the wake of its success, catering to those who aren’t content with having only one transformational week a year. One of the more visible parts of this movement are “transformational festivals,” a term coined and popularized by Canadian filmmaker Jeet Kei Leung in a TEDx in 2010. Mid- to upmarket, from Wanderlust to Tribal Gathering to Lucidity to Further Future, a weekend does not exist during which one could not jet off to a scenic location such as Tel Aviv, Tulum, Panama, or Oahu to experience something that “is more than a festival.” Per Panama’s Tribal Gathering, “It is a place for the world to come together, where time is transcended, ancient and modern converge in symbiotic harmony… It is a gathering of tribes, from the past and present, the global transformational tribe.”[ii]

Such transformational experiences are serviced by a cast of tanned northern-hemisphere men clad in kaftans playing slowed-down tech house with “ethnic” samples from altar-like DJ booths covered in candles, a motley vibe tribe of self-titled “epiphany junkies,” “wonder addicts,” and “curators of awe,” and ayahuasca shamans pivoting into branded microdosing entrepreneurs. Wanderlust, in Hawaii, is described as “not a final destination: it’s a path, a journey, and a yearning to explore and connect to your life’s purpose.”[iii] California’s Desert Hearts “isn’t just another meaningless party. This is about finding a new kind of freedom. A point where you reach your mental breaking point and come to your specific realization that is meaningful at exactly the right place, exactly the right time, and exactly the stage of life that you are currently in.”[iv]

A lot of this reads as a reaction to the “white people have no culture” predicament — a search for meaningful spirituality from a global cross-kitchen smorgasbord of spiritual practices when every meaningful tradition one’s own culture has been turned into yet another hollow, thematized consumption opportunity. The irony of all of this is of course that transformational festivals and their spiritual offerings are becoming increasingly codified and prepackaged into a luxury service industry in its own right, a distributed “countercultural Disney World” that markets an existence where one doesn’t need to ever leave the metaphorical Playa.

Without discounting the real, lived experience of those on their transformational journey quests, we are bumping against the hard limits of the experience economy here: How many true transformational experiences can one have? In the end, escapism isn’t freedom, and transformation isn’t revolution; being on a year-round transformation festival circuit hardly realizes the idea of permanent revolution. Being a transformational experience junkie is in the end just being a junkie — even if a fun kind — while one’s journey is in a holding pattern. It is exactly analogous to psychedelic drugs (which of course lie at the core at many of these experiences): the refactoring of everything induced by a trip can be a life-changing event, but over time the epiphanies start to repeat themselves and fall into predictable patterns (all is one, etc.), ultimately approaching the ultimate meaning monster, the void at the end of the tunnel. All this amounts to little more than an entertaining form of killing time unless it is integrated somehow into one’s understanding of, and actions within, baseline reality.

So, back to the original question: How should we look at the Smithsonian exhibition? Problematizing these decontextualized works themselves that actually operate more as set designs and props than visual art seems pointless. The title of the show is a reference to a long-standing Burning Man saying: “No Spectators.” Everyone is a participant, or, in International Art English, the distinction between subject and object has been dissolved. This seems like a tall order in a setting like the Smithsonian. Yet the exhibition might be best approached and understood within the larger framework of the experience economy — as a supposedly fun, non-transformational experience itself.