In 2009, Brigid Mason produced a painting titled Saudades (Our Chair is the Same). The painting depicts two wooden chairs, one pink and one green, woven together at a front corner by the wicker of their seats. This image has since recurred frequently in Bunny Rogers’s art practice. It was 3-D printed in miniature for Jasper Spicero’s “Open Shape” series in January 2013; was fabricated in full for the Rhizome event “Internet as Poetry” at Issue Project Room, New York, in July 2014; and has been echoed in the composition of reproductions of Columbine High School chairs (Clone State Chairs, 2014) in the artist’s “Columbine Library” exhibition at Société in Berlin, which closed in September this year. When 3-D printed, the chairs are connected by shared plastic. When fabricated full-size, thus far the most faithful to Mason’s image, it is the woven fiber of the wicker that connects them. The chairs that appeared in “Columbine Library” were not physically connected, but were paired and positioned in the same manner as in the original painting, and they were connected, perhaps, by the idea itself. Illustrations of chairs by Mason flow through Rogers’s recently published archive of poems, Cunny Poem: Vol. 1, alongside portraits of Mason and Rogers.

That a work by another artist should offer the entry point into Rogers’s practice might at first seem derivative. Instead, it is a clue with which we can begin to unravel the multiple connections that populate her art. Rogers works or has worked closely with a cast of collaborators such as Elliot Spence, Spicero, Filip Olszewski and Leo Fortelius-Moring, as well as Mason. The hermetic logic that breeds self-identification with a character like Joan (from the discontinued TV series Clone High, which aired for only one season between 2002 and 2003), into whom Rogers has superimposed her subjectivity in a series of fifteen self-portraits, becomes a type of precision among fellow perpetrators.

Rogers became known online for her provocative and honest portrayals of self, developing an art practice that has since expanded into the gallery space through a deft and carefully labored devotion to hand-rendered sculptural objects: clay herons, dyed roses, beaded bags, blankets. Recently, she has instigated a shift in her practice toward outsourced fabrication, employing in one work (Clone State Bookcase, 2014) a furniture company in Wisconsin to produce a more than life-size replica of the Columbine High School library bookcase, stacked with 168 Limited-Edition Elliott Smith plush dolls — soft toy caricatures of the late singer-songwriter modeled on a marshmallow food item from the game Neopets. Italian theorist Maurizio Lazzarato has claimed that, within contemporary capitalism, a company no longer produces just a product or service, but produces a world. Artists make worlds too, and Rogers’s attention to detail runs beyond her characters and into the types of clothing and furniture that socialize them.

Do two chairs tied together make a world? Worlds happen when they are reproduced, and there is a logic of repsroduction implicit in Rogers’s identification and repetition of certain symbols, just like there is a logic of reproduction inherent in the advertising strategies of the company that wants us to wear a certain t-shirt or install a certain operating system. What happens in this moment is the reproduction of not just an image, but an array of material and linguistic signifiers that combine to create this image. The meaning of an image happens in the connections between these distinct but cooperating entities. Where Rogers positions herself as an artist is in this holistic reproduction of the image as a world, rather than in the image as an isolated or captured moment. Her poems provide the imagery for her artworks, and her artworks provide the worlds for her poems. These are tied together by a relentless portrayal and decentering of self across mainstream social networking sites as well as the more obscure communities of Second Life, Neopets, Furcadia and other worlds. One thread between two chairs is an accident. Weave these threads together and you have a library.

The word paraphilia describes a condition in which someone’s sexual gratification depends on behavior that is atypical or extreme. Common paraphilias include exhibitionism and voyeurism, but also sexual fantasies or acts involving nonhuman objects. Rogers’s work has from an early stage explored the complex relationship between the strength and vulnerability of the young female subject under the voyeuristic, predominantly male gaze. Plushophilia is the term attributed to paraphilias involving stuffed animals. Autoplushophilia is a term suggested by American psychologist and sexologist Dr. Anne Lawrence to refer to sexual arousal that depends on imagining oneself as a plush toy.

Rogers’s work often attempts to dislocate straightforward connections between sexuality and desire. She will sexualize the non-sexual or desexualize the sexual to disrupt simple assumptions. The world that she creates in an exhibition like “Columbine Library,” and the worlds of her objects at large, is one that attempts to complicate power structures under the hegemonic male gaze while refusing to submit to this gaze. Plushophilia constitutes a nonreproductive sexual relation. Plushophiles are sometimes referred to as “plushies,” meaning that both the subject that desires and the object that is desired can have the same name. As Rogers incorporates a wider array of outsourced production techniques and furniture design into her practice, alongside her more haptic craft-based objects, she continually questions ideas of who or what has agency in her multifaceted installations, and who or what things might form relationships that create this agency. Rogers’s work doesn’t suggest any resolution to these connections. She brings them into her world as suggestions, perhaps, of avenues out of our current shared ways of structuring reality. She challenges the means of her own reproduction.

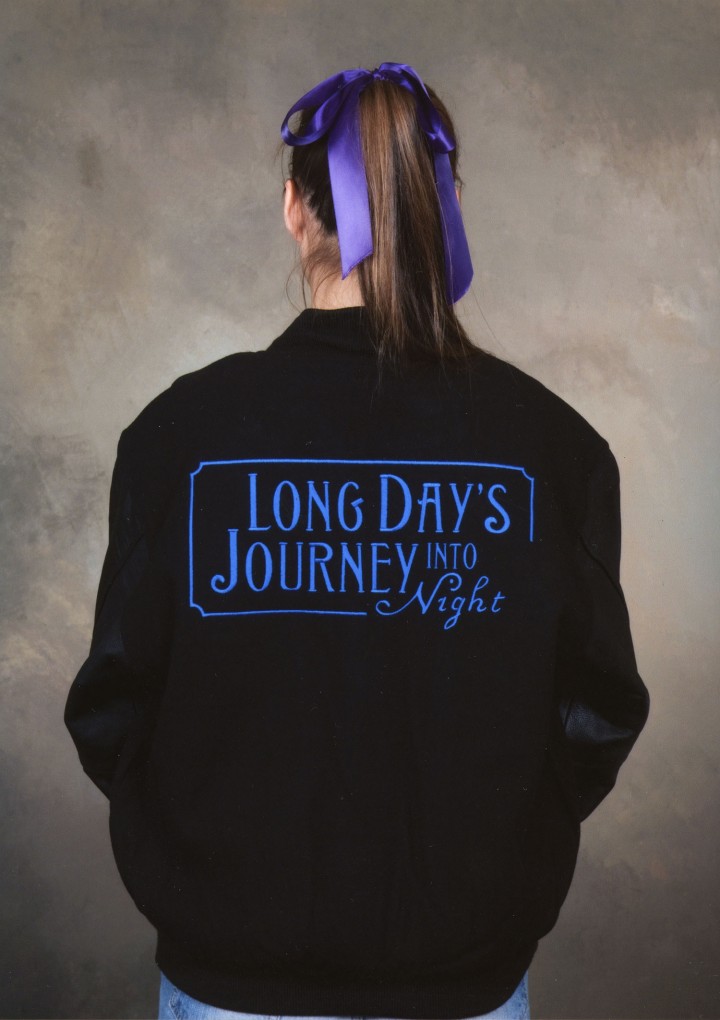

Performance, text, video, object and embroidery overlap in Rogers’s practice to question common assumptions of identity and the identity of objects. In the cover artwork to her recent book of poetry My Apologies Accepted (Civil Coping Mechanisms, 2014), which features two illustrated portraits by Brad Phillips, Bunny is portrayed sitting with her back to the camera (we assume it’s a camera but it might just be our eyes). Perhaps it is not the act of looking but the system of looking that induces the paraphilia. In front of her, on the wall, is a ribbon. She is sitting on a single chair. Every portrait is a betrayal.