The Absurd

Wouldn’t it be convenient to introduce this essay by noting a general euphoria surrounding Bruce Nauman in the international art world? It would have legitimated my critical analysis of Nauman but also have led me straight into something disagreeable. Because at the end of the 1980s only a small, established part of the art world was shouting “Yes Bruce Nauman,” and it strikes me that the enthusiasm of the curators, collectors, museum directors, and critics has faded in the meantime.[i]

I actually wanted to discover what need Bruce Nauman’s works awaken and satisfy, and the extent to which this might be read from the reception of Nauman’s work. But as I had already decided to regard Nauman as an artist who doesn’t jolt the self-image of the culturally bourgeois individual, show him the human abyss, or allow him to experience the absurdity of his experience, this view could only be confirmed retrospectively. For Robert Pincus-Witten in 1973, it was still natural to speak of the “fertile role” that the “untitled rubber, fiberglass, and neon works” played for the “reorientation of artistic inspiration” in the late 1960s.[ii]

Pincus-Witten isn’t referring to the body art, video, and performance aspects of Bruce Nauman’s work, which was an important point of reference to artists in the ’70s, but talking expressly about the fiberglass and rubber works. He joins in with the opinion that the very choice of fiberglass — a seemingly organic but actually industrial material — breaks with the rigid forms of minimal art. In fact, fiberglass satisfied the post-Minimalist yearning for tactility. Nauman’s early pieces (all “untitled” and mostly produced in 1965) are arched or curved and take their bearings less from the given conditions of the space than from the measurements of the artist’s body. In a work like Untitled (Eye-Level Piece) (1966) participation is taken literally: it occurs at eye level.

This makes me wonder to what extent it can be a positive trait for a work to become a nuance, a slight deviation within a canon — the canon, in this instance, of minimal art. Or is immersion in the existing canon indispensable because diversions sometimes give rise to radical statements?

Pincus-Witten sees the humor, the puns, and the jokes in these pieces as pioneering, partly because they mark a return to Duchamp. But for me this humor doesn’t work. Was it really ever funny? For example in the piece From Hand to Mouth, in which a figure of speech is taken literally and the physical distance between the hand and the mouth is shown. I get the same feeling of polite laughter with Wax Impressions of the Knees of Five Famous Artists (1966). In this case the title conveys the joke that the hollow shapes can’t be explained with reference to the knees of famous artists. The joke lies in the Dadaist discrepancy between object and title. Maybe it worked in the past, but today the joke’s gone a bit flat. This has to do with the way humor works, always referring to a particular present. Humor can’t be preserved, being bound up with particular situations and linguistic conventions. Nauman, who both modified and complemented minimal art, was an early exponent of “American sculpture.”[iii] The artist then reactivated the so-called legacy of Duchamp and mobilized an awareness — always there for retrieval — of the absurdity of the whole. The absurd was and remains the spice of cultured existence: things that aren’t immediately explicable, that have no meaning, a play by Beckett, Ionesco, or Camus. The fascination with the absurd has been rekindled time and again since the 1950s because it draws support from schools and cultural programs, of which absurd theater forms a crucial component. Can we compare Waiting for Godot with the lonely and absurd studio activities of Bruce Nauman?

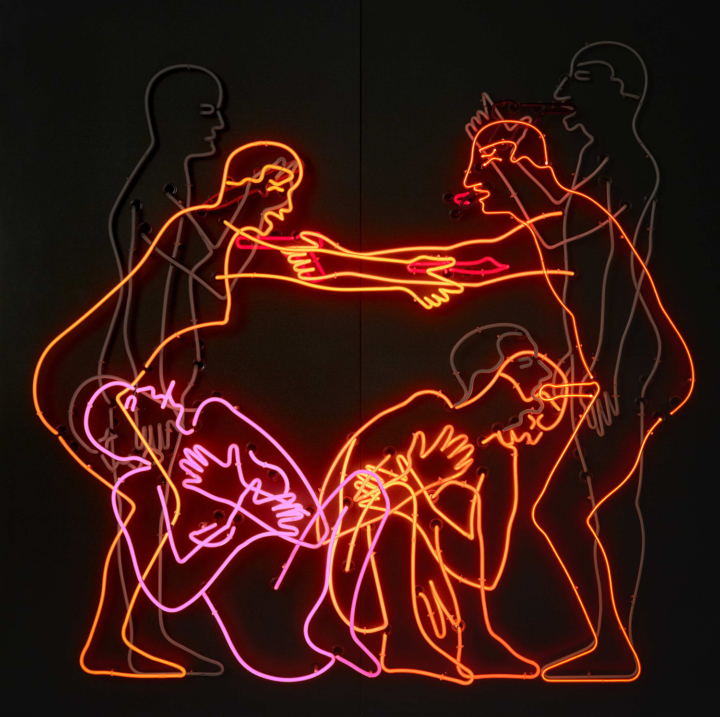

It might be claimed that every generation of artists goes through the radical chic of alienation. Bruce Nauman says that the reading of Wittgenstein was a drastic experience for him. Many visual artists are interested in Wittgenstein’s skeptical aspect, his critique of rationality. Wittgenstein’s thoughts about language are appropriated for an artistic “end game” aesthetic, which in some circumstances ends up in pessimistic mourning over the state of the world. Nauman’s neon work Raw War (1979) represents this arbitrary connection (which isn’t Wittgenstein’s fault) between language games and a taste for the apocalyptic.

One almost has no choice but to say that this work is a representation of the absurdity of war.

Bringing the idea of language games and the absurd so explicitly into play amounts to an attempt to guide the reception of the work. Jean-Christophe Ammann promptly reacted, and called his catalogue essay “Wittgenstein and Nauman.” As if guided by a ghostly hand, he immediately begins to speak of the “existential dimension” in Nauman’s works.[iv] His works from the 1960s still deal with his alienated relationship to himself and to things. As a fountain (Self-Portrait as a Fountain, 1966–67) he was not at one with the world, and yet he was sufficiently at one to establish and enjoy the fact. The subject — whether Nauman himself or the spectator — always remained untouched. Donald Kuspit still raves about the disorientating experience to be had in the Nauman Corridor, in which one feels blind and at the mercy of the system.[v] If I now look at Nauman’s photograph Cold Coffee Thrown Away from 1966, I immediately think about the zoom shots in Blue Velvet (1986) and the statement, which always strikes me as suspect: “It’s a strange world.”

Nauman exoticizes his artist’s body or, as most critics put it, he makes the familiar strange, mobilizing precisely the same vocabulary that J. Hoberman used to describe Blue Velvet in his book Vulgar Modernism: in individual shots Lynch takes familiar things out of context and brings them into close up because it makes them appear stranger. But does it seem now unpolitical to have such an aestheticizing and alienated relationship toward oneself and one’s surroundings? How could this “unpolitical” be described? In the process of impartial recording, the possibility of any analysis of social connections goes missing. And these relations can be observed; the imaginary has its own rules. Every David Lynch zoom has something ahistorical about it. History is excluded.

Pincus-Witten made a funny distinction in this context, between Californian and New York artists: “The distinction is between being and doing.” This observation was intended as a discrimination against L.A. art, and was more a rhetorical flourish than an empirical observation. But once more it placed the emphasis on existence: Californian artists, and Nauman in particular, says Pincus-Witten, deal more with questions of artistic existence and less with issues of artistic production. The ideology of alienation that is part of existential philosophy is now an integral part of the bourgeois self-image. This attitude had a certain radicality at the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s, in that it was aimed against the terrorism of honesty and confession of our parents’ generation. Nauman’s 1987 video Clown Torture (I am Sorry and No, No, No) has received the enthusiasm of many collectors and curators because of its supposedly unbearable toughness. Young existentialists, who profess not to understand anything in the manifest world, consider themselves equally tough and uncompromising.

This doesn’t mean that a youthful sense of alienation necessarily goes hand in hand with an enthusiasm for Bruce Nauman. But Nauman speaks to those people who have saved up their former alienation for culture, and like to see it confirmed there — you and I included! When people talk about the hardness of many Nauman videos it reminds me that Dennis Hopper in Blue Velvet was seen as the incarnation of unbearable violence and brutal toughness — and people loved him for it. This is a comparable fascination with a cultural phenomenon that is seen as highly expressive and rich in content, even if it shows nothing more than the violence contained in everyone.

Commitment

Nauman has always been concerned — even in the neon sign The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (1967) — with prolonging the bourgeois illusion that there is a position within society from which society might be coherently described for someone else.

For example with his corridors or “musical chairs,” which supply a commentary on subjects like sensitivity, the coldness of existence, or violence. One of the fundamental characteristics of these commentaries is that they are made by a distanced but perplexed individual. I have heard collectors refer to Nauman as a humane artist. They can identify with this type of symbolic commitment. If artists symbolically lament the pitilessness of the world, they are fulfilling the wishes of a culturally pessimistic strain of conservative rebellion that likes to revolt against violence, progress, and the culture industry.

Nauman doesn’t tell us anything about the precariousness of his own identity as an artist, about any influences, struggles, or models to which he might have been exposed. Instead, the “musical chairs” set associations in motions that give him the aura of the politically engaged artist.[vi] Julian Heynen believes that the physical experience of torture was conveyed to him in this piece, and thus shows how Nauman satisfies social needs for a radically avant-garde, tough artist. It’s as if early in his career Nauman had taken on board the sense of political consternation (politische Betroffenheit) that is again subject to widespread critique in Germany today. He always maintained the framework of the individual creative artist, whose lonely studio activities are art.

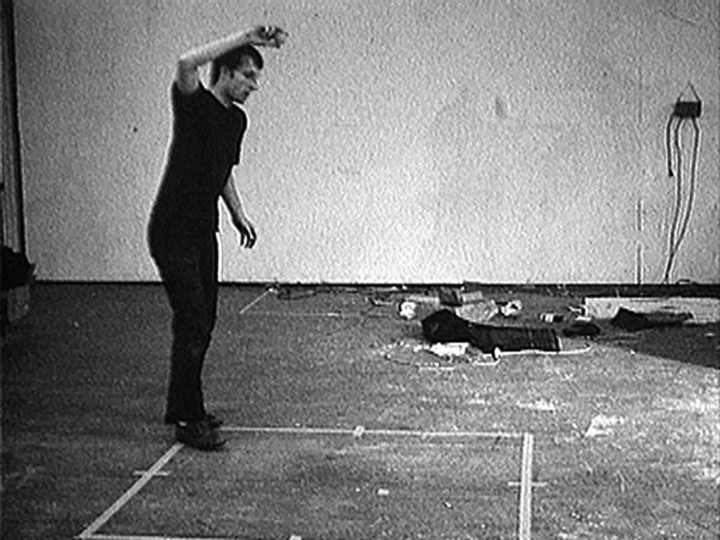

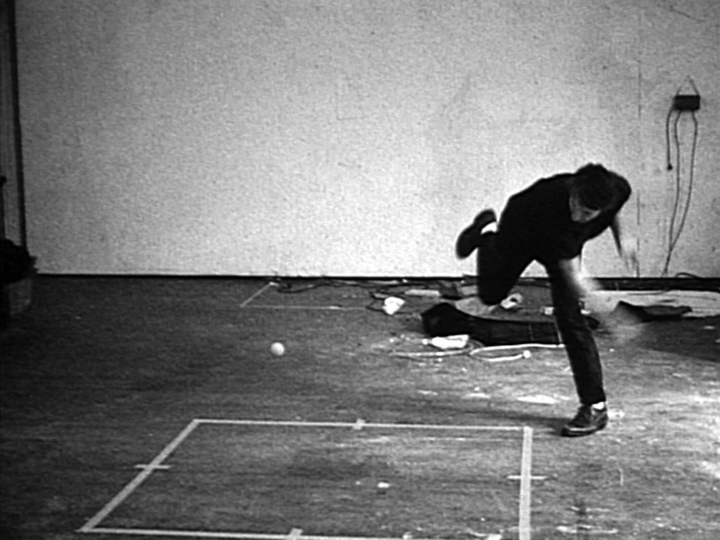

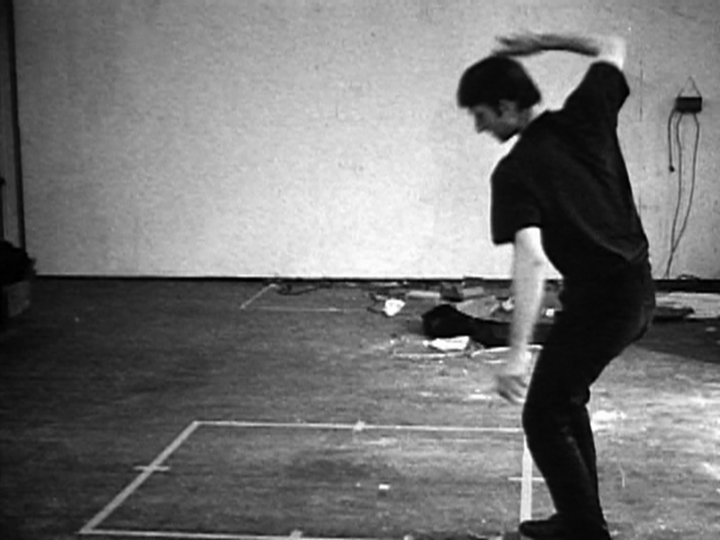

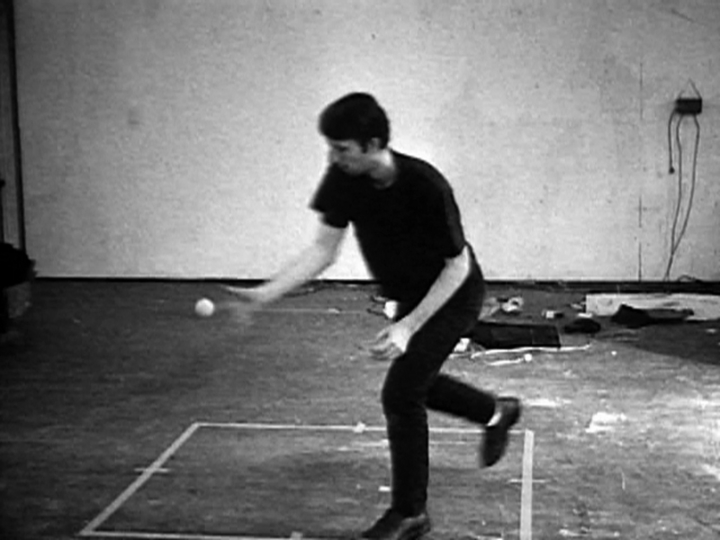

The videos Playing a Note on the Violin While I Walk Around the Studio (1968) or Bouncing Two Balls between the Floor and Ceiling with Changing Rhythms (1968) deal with the studio artist’s ways of dealing with himself. Abandoning communication. The social relations that make the recognition of an artist possible are faded out. Nauman reinforces the social idea of creativity as individual potential that need only be persistently lived out if it is to be acknowledged. His videos are always the product of isolated activity; nobody else (wife, family, friends) ever appears in them. Influences conceded in interviews are restricted to those of other artists (Moore, de Kooning, Johns, Tuttle).

Even in the 1970s Nauman was praised[vii] for physically involving the viewer. But the body that Nauman involved had neither gender nor class. In the ’70s it was considered radical enough for the white male middle-class body to be exposed to experiences of “isolation” and “alienation.” Perhaps the involvement of the universal body was a first step toward its ethnic or sexual differentiation.

Nauman’s body lays claim to universality. This is made apparent in generally applicable neon sculpture, like Neon Templates of the Left Half of My Body Taken at Ten Inch Intervals (1966). We might in retrospect think highly of this universalism were we to act as though Nauman had anticipated what Ernesto Laclau formulates in these terms: in every particularism there lies a universalism. Applied to Nauman this means: one of the qualities of Nauman’s specific body is that it wants to be universalized. And part of the specific problem of this essay is that it sounds as if I wanted to accuse Nauman of “artistic deficits.”

That wasn’t my intention. Rather I wanted to work my way into the themes that arise in his work: existence, absurdity, alienation, language games, and later, commitment and perplexity. What willingness, what wishes does Nauman reckon with, what viewer’s or collectors demands does he take as his starting point? Here the fundamental question arises: to what extent can an artist be held responsible for his reception? When Nauman drops names like Beckett or Wittgenstein he is guiding the way people write about him. So I would seek to claim that in Nauman there is a correspondence between his cultural project and his critical reception. And I would be surprised if Nauman felt utterly misunderstood by, for example, Coosje van Bruggen or Pincus-Witten.