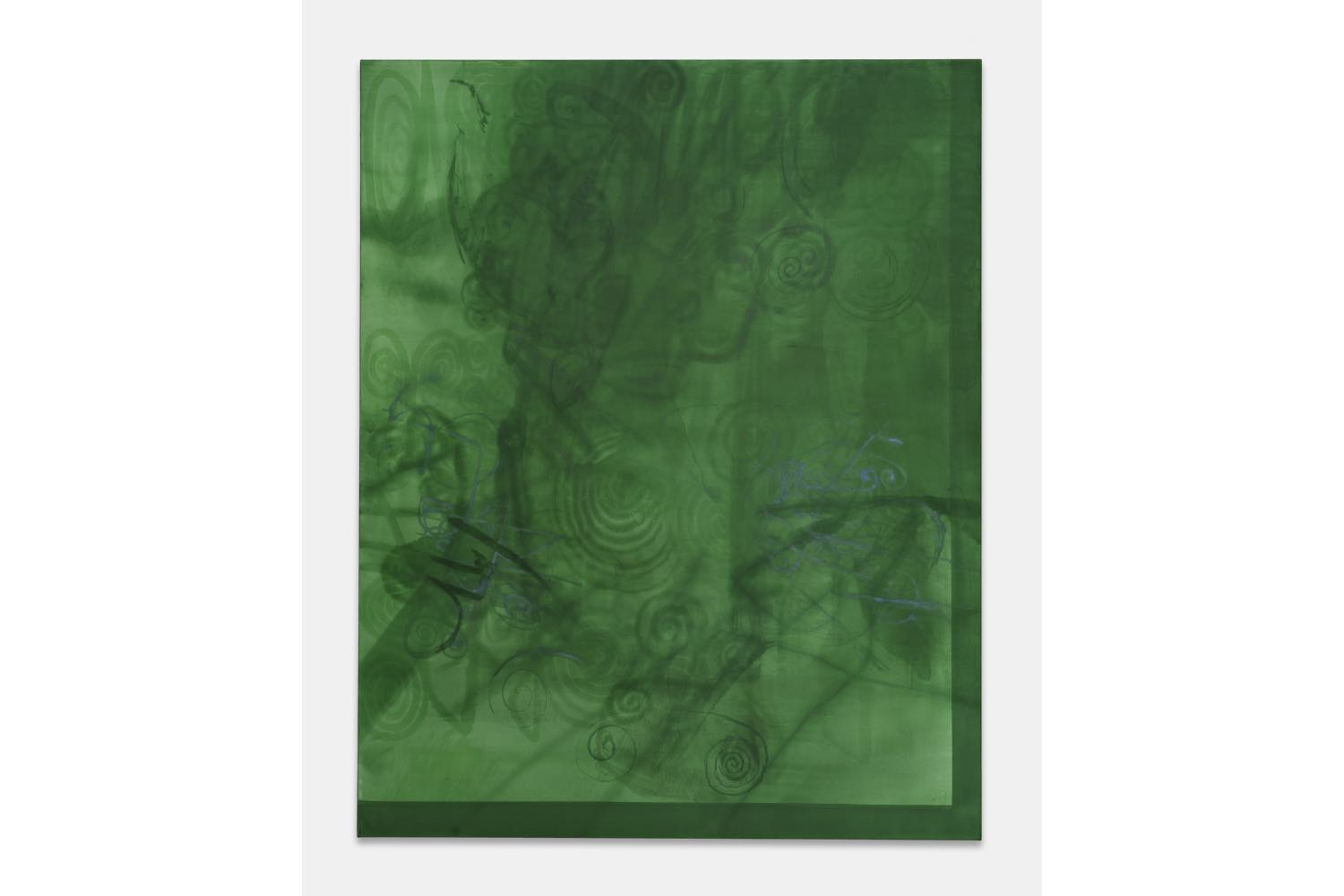

“Everything is fiction,” Brook Hsu has said, “but fiction is also one of the most powerful things for us to describe reality.” The green that frequently bathes her fairytale forests, sobbing demons, and apparitional portraits is poem and material: leaky and seeping, with puke and toxins and nature and growth, green-eyed and green-screened, a soothing wavelength for the eye, and the simulation realm in The Matrix. As in the oft-cited ’90s cyberpunk trilogy siphoned into cultural shorthand for everything from internet omnipresence to “red-pilling” dog whistles, Hsu’s work can be read as a reaffirmation of reality when the world’s organizing beliefs are sick beyond metaphor. Imbued in this lens, blurred and “green-pilled,” is a conviction that we are unfixed porous beings, absorbing and bleeding into images and stories we tell ourselves or the places that find us.

The artist’s practice is often considered in terms of autobiography via symbolic myth. It’s not unusual for an artist to use themself as an entry point to something more “universal,” but I would argue Hsu more self-reflexively treats the texture of her storytelling as a material conduit for how narrative travels through us and, in turn, shapes what surrounds us. There is no grandiosity or self-seriousness as she abstracts the stuff of existing into micro-memories and hyper-specific references, sediment of multivalent narrative synchronicities-cum-corporeal knowledge. Driving down a dry dirt road in Oklahoma, listening to Björk, then dating Matthew Barney, whose “Cremaster Cycle” (1994–2002) Hsu recalls watching in a “dumpy house next to a Stonewall Jackson bar lined with Civil War reenactment maquettes.” This psychophysical web is the southwest-midwest landscape circa the early 2000s where she grew up.

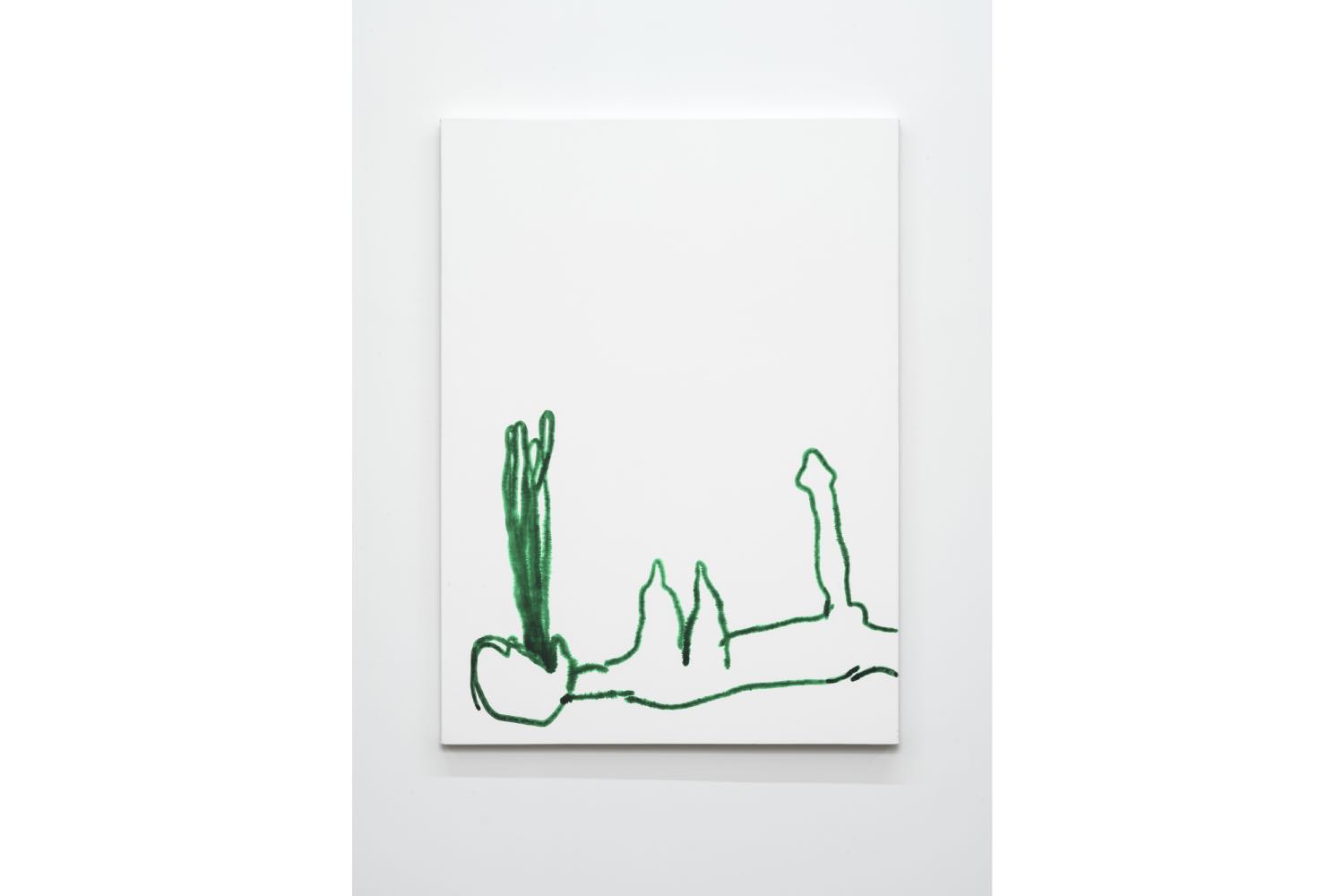

Hsu identifies most readily as a painter of landscape, a tradition long associated with truth through distance and displacement. Ironically, the artist finds herself reflected here, as an outsider to the persisting white male ideology that to know something is to step back from it, to Other it. Her vantage is related to timely resurrections of plein-air observation and wistful cottage-core flower fields longing for the earth, but also slightly adjacent through her distinctive synthesis of remembered, imagined, and quoted environs, mining a time warp of Greek mythology, romantic literature, children’s animation, and Wild West Americana for allegories of isolation, love, sex, death. The things. Old Master realism, Romanticism’s affect, and Impressionism’s positivist view of light and color accumulate in her work as a reality check. Yes, worldviews have always inscribed images and the innermost corners of self. Hsu takes this into her own hands by using images to transfigure her encounters with death via her mother’s terminal illness into the less scary face of a skull’s natural grin or of her dog, Aesop, as a lanky ghost and fable, which abstract her memories into a form that can transmute feeling into something less acute.

But as the artist articulates, the earth, too, has its own memory and resistance to what can be easily made legible:

We don’t think about the internet being something that’s like a drug, but I think it gets treated a little bit like it’s everything. And it really doesn’t have or carry all our knowledge. A lot of our knowledge is outside of it, in the things we’re surrounded by.

In Hsu’s case, knowledge exists in pastoral scenes and woodlands lifted from the backgrounds of Northern Renaissance and Baroque paintings alongside those she knows intimately or invents. Lovingly rendered tree canopies, soft and airlessly still with patience, register the melancholy of what’s typically relegated to the margins or adrift with affect. In lavishing attention on thickets that bend in the wind, huddle together, or take a bashful center stage in rich greens, browns, and reds, Hsu makes landscape as something seen something seen into that is substantively part of us yet perpetually unknowable. And, if the world can’t ever really be known; maybe we don’t have to be, either.

Writing on Yayoi Kusama in a 2023 essay titled “Vanishing Point” for Texte zur Kunst, Hsu asks how her own attempt at making sense of life through image-making, which she calls “complete annihilation,” differs from Kusama’s notion of “self-obliteration [as] becoming one with many, where we are ‘returned to the natural universe.’” In delicate contrast, Hsu’s interest lies in the ways self and emotional states can disperse, metamorphose, and reappear through the universe’s mercurialness. As Björk says: “Then the body memory kicks in / I mime my home mountains / The moss that I’m made of / I redeem myself.” Or, in a bit of variation, a poem printed on silky fabric in her first solo show, “Panic Angel” (2017), at Deli Gallery: “in life, Eros [the god of love and sex] was a painter who only painted butterflies / and the butterflies were all Eros’s psyche / and / even though psyche experienced trauma / being Holometabolous / transmutes.” This confession of pain and sorrow hoping to be alchemized alludes to hand-painted impressions of an ear overlaid with sweet fairies, butterflies, and other winged creatures in femme pastels, their phosphorescent glow akin to seemingly magical properties of the earth’s metamorphosis — and the equally fantastical transference of human connection via air particles, light, vocal cords, and bodily appendages.

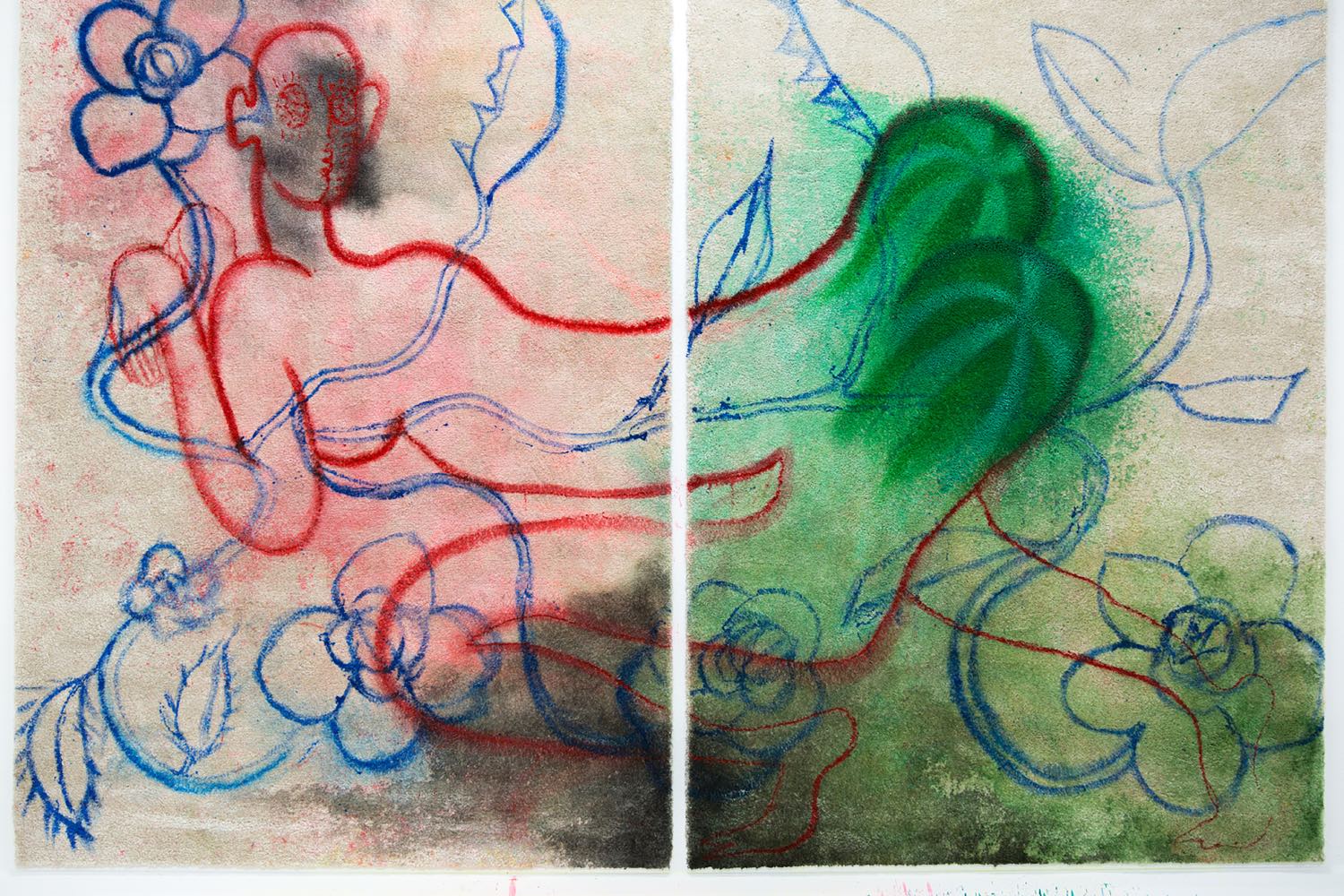

In Hsu’s 2019 exhibition “Conspiracy theory” at Et al., unknowability or excess beyond understanding become subject matter, as in landscape with skeleton and reflecting pool (2019), one of several motifs depicting poured and pooling liquid (often bodily fluids). Here, a skeleton with horns (the figure of Death) spews tears into a well against a misty valley. The work’s support is shaped as though to frame a miniature cathedral threshold, acting as a framework of belief or devotional object that claims inherent meaning. As filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky wrote, and who Hsu cites in her slow and dreamy landscapes: “A symbol contains within itself a definite meaning […] while metaphor is an image. An image possesses the same distinguishing features as the world it represents [with] indefinite meaning.” Unable to see itself reflected in its gushing tears, the creature embodies the indefiniteness of what it really is to be human in this world, the opposite of Narcissus. The process of working in wet-on-wet or glossy surfaces (PVC, soaked canvas, water-logged carpet of the best dreary beige assortment) gives shape to what Hsu’s work describes as an indefinite muck of representation, letting green and material at large assume the protagonist role. Serving to abstract fictional characters from new-wave Taiwanese and Japanese cinema and to distort loopy symbols of horses, hares, frogs, hearts, or text like “BABY,” and high-heeled boots into the metaphor of drenched surfaces, Hsu’s inky runny wash dissipates and recovers figures in their surroundings. In skeleton cry-vomiting into its reflection (2019), the Death character appears in drips of shellac made from female lac beetle secretions of tree sap reminiscent of the color of antifreeze: poison in the water, or a liberating formlessness of being in vertigo, the ground on which her characters stand blurred and smeared. In the painting grasshopper (2021) from her 2021 exhibition “Fictions” at Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, a rabbit drawn in multiple in smudgy green on carpet deteriorates in clarity, recalling the media dissociation of Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” (1962–67) series and other instances of reality’s mutability: Muybridge’s proto-cinematic horses, evolutionary diagrams, Duchamp’s Bride Stripped Bare (1915–23), even Turner’s nostalgic bunny quite literally obliterated in the aging surface of Rain, Steam, and Speed (1844).

Everything at warp speed, ever-present representations careening into real-time from the depths of cultural memory:

Are we all just about to be image corpses, violently throwing up the bile of it all at the end? See Untitled 1 (vomit/boobs/dick) (2018). In her recent installation in the desanctified church- turned-gallery Sant’Andrea de Scaphis in Rome, the artist buried a miniature painted copy of the pregnant Madonna from Piero della Francesca’s Madonna del Parto (Our Lady of Childbirth) (ca. 1460). Also reproduced in Tarkovsky’s 1983 film of homesickness and mysticism in a ruinous Tuscany countryside, Nostalghia, the Madonna (here cropped to only her face and thus severed from “female duties” of reproduction and motherhood) gives way to collective placelessness, dissolving when viewed from a few steps back into the green monochrome line along the room’s perimeter. Among equally miniature paintings of skeletons nuzzling and fucking, the icon considers what has emerged from the dead. But the author surely hasn’t, as they have never really gone away. Hsu’s work posits, instead, that they are subsumed in greenwash and a recognition that reality can be found in the annihilation of distance between symbols, places, others, narratives, and selves — even in the “purified” and “secular” space of abstraction. It might be time to revisit postmodernity, or retrieve a version of it, in which “authenticity” and the genuine do still exist but are entwined with fictions we’ve made of it. Hsu jokes about being labeled a “scorned woman” painter, and of course, we know by now that no space or context is neutral, but it’s necessary to call out that the artist’s subjectivity and projections onto it are also always present.

One of the first of Hsu’s works I saw in person was Earth Angel (2017), sprawled on her studio floor. A carpet painting caked with the residue of age decorated with a blue floral vine motif and chimera figure, the work bears several stains. Hsu explained she loved the stain as a form: “I saw it as a process of acceptance.” However, acceptance doesn’t mean avoidance of grieving for someone or something, giving up on life, or political impotence. As she articulated, “It’s trying to understand how much weight things can carry or how much weight we put on, meaning sometimes something is there, and people really didn’t think that much about it […] and then having to accept that this stain is now there.” In other words, acceptance is ultimately unexpectedly freeing, giving you the agency to move forward from the reality you’re in, however uncertain, uncomfortable, or painful. Myths of wellness culture might recommend an ice bath to cure all ills, but when coming back to consciousness between waking and hallucinatory thoughts, it helps to just grab onto the cold bar of your hospital gurney to recognize yourself among the material world. A stain, a landscape, a pool of tears, a cold touch to the skin: it’s at least a start to remedying the illusion of detachment and false belief that this is a simulation.