It was then that she summoned the spirits. In 1965 the English-born Bridget Riley broke from the traditions of painting, and systematically challenging optical uncertainty. Her striped images were revolutionary. No other type of painting concerned itself with sight so concertedly before. Only shortly after she roused these spirits were they no longer resistable. Almost excessively, popular culture copied Riley’s geometric patterns, transferring them onto miniskirts, curtains and rugs. At the time the painter hopelessly fought this mass plagiarism with copyright laws. She felt misunderstood and used. Ultimately her intention was strictly aesthetic and consciously educational. She wanted to confuse the public and activate sight. For her, it was a horror to be a pop icon. She did not understand her work as a commodity, but rather as fundamental research into Primary Perception.

Today, presented in a museum-like fashion at Max Hetzler, these battles with modernism still reverberate. The geometric paintings on canvas flicker, writhe and warp our retinas and in so doing appear three-dimensional. These paintings move with astonishing dynamism without losing their form. Riley was able, in her own way, to connect European Konkrete Kunst painting with the painterly concerns of the Impressionists. And so she employed experiments in the style of Pointillist Georges Seurat. She continued to develop more complex color-form structures. Fluid but certainly controlled, the painter is in dialogue with her experiments with color, form and negative space. Here lies the meaning of seeing: “Color fields dissipate into particles, which only come together in the eyes of viewers.” One reflects on the phenomenon of perception while looking at images with poetic titles like Delos, Arcadia and Revision of May. The painter of these Op Art landscapes is a descendant of the Impressionists. Her art comes from their ideas but her images decide the impression. Everything seems fleeting. The elements appear to disperse into light and shadow. Form becomes color.

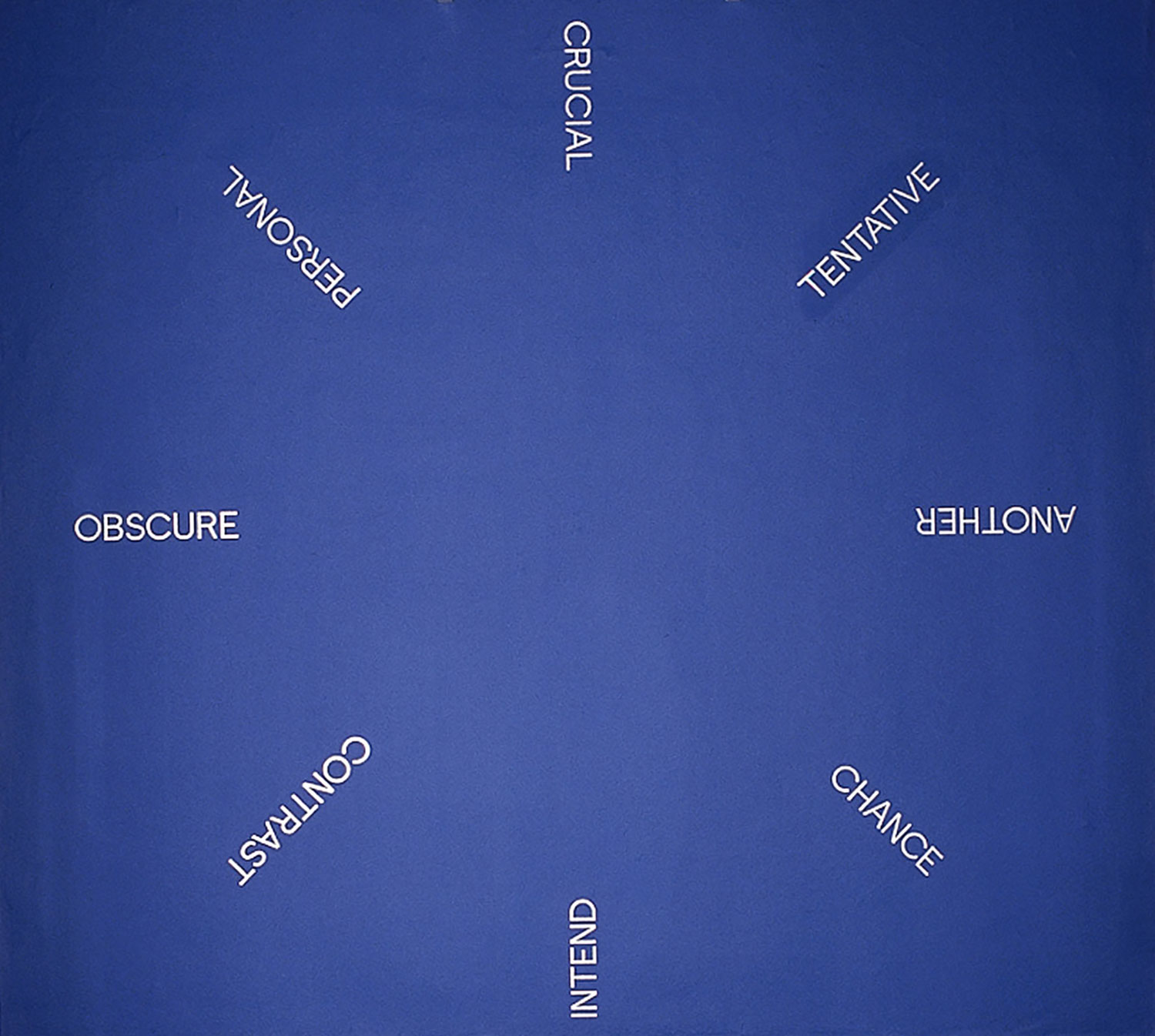

In the Red With Red Triptych (2010) a more direct contrast between two red tones and a deep blue arises. The lighter red suggests flames, which devour the darker red and the blue that becomes evermore violet. The examination of perception achieves radical effects. A confusing beauty without certainty is created, though this is not entirely intentional. Then, everything disappears, as long as one turns away. Stepping close to the painting’s surface one encounters the diagonally ordered color geometries as pixilated surfaces. Through distance the paintings achieve, sometimes in cool, sometimes in brilliant tones, an elegant, vivid quality. To this extent Riley is capable of expanding the boundaries of optical illusion. This is especially the case when set against a pristine white wall. One such example was installed in the gallery like a geometric sculpture. Composed in black, like a rotating compass, Composition with Circles 4 (2004) is like a meditation field — calmingly beautiful. For the now 80-year-old Bridget Riley (the latest artist to be honored with the Rubens Prize by the city of Siegen, Germany, the birthplace of the baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens) it’s not about recognizing real things. It’s about impressions on the senses: not form, but rather color; not things, but rather light that becomes the fundamental inheritance of the Impressionists.