Blinky Palermo is a near-mythical figure in postwar art, partly because of his biography, partly because of his pioneering art, although his modernist sensibility was almost anachronistic when he developed his style in the late ’60s. Palermo was fascinated by the paintings of Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, when Abstract Expressionism was everything but en vogue. And he showed a pursuit for the spiritual, under conditions when it could not be sustained. Benjamin H. D. Buchloh called him a “catastrophic romantic at a moment when you couldn’t be a romantic anymore.”1 Palermo’s oeuvre remained small, not least because of his premature death at the age of 33. His work is reticent and purist, but also evokes something poetic, if that term wasn’t so worn-out when applied to art. Far from being figurative, Palermo was never entirely an abstract artist either. In contrast to his artist friends — Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, Imi Knoebel — he gave up painting soon, just to inquire more intensely on the nature of painting beyond the mere use of paint and brush.

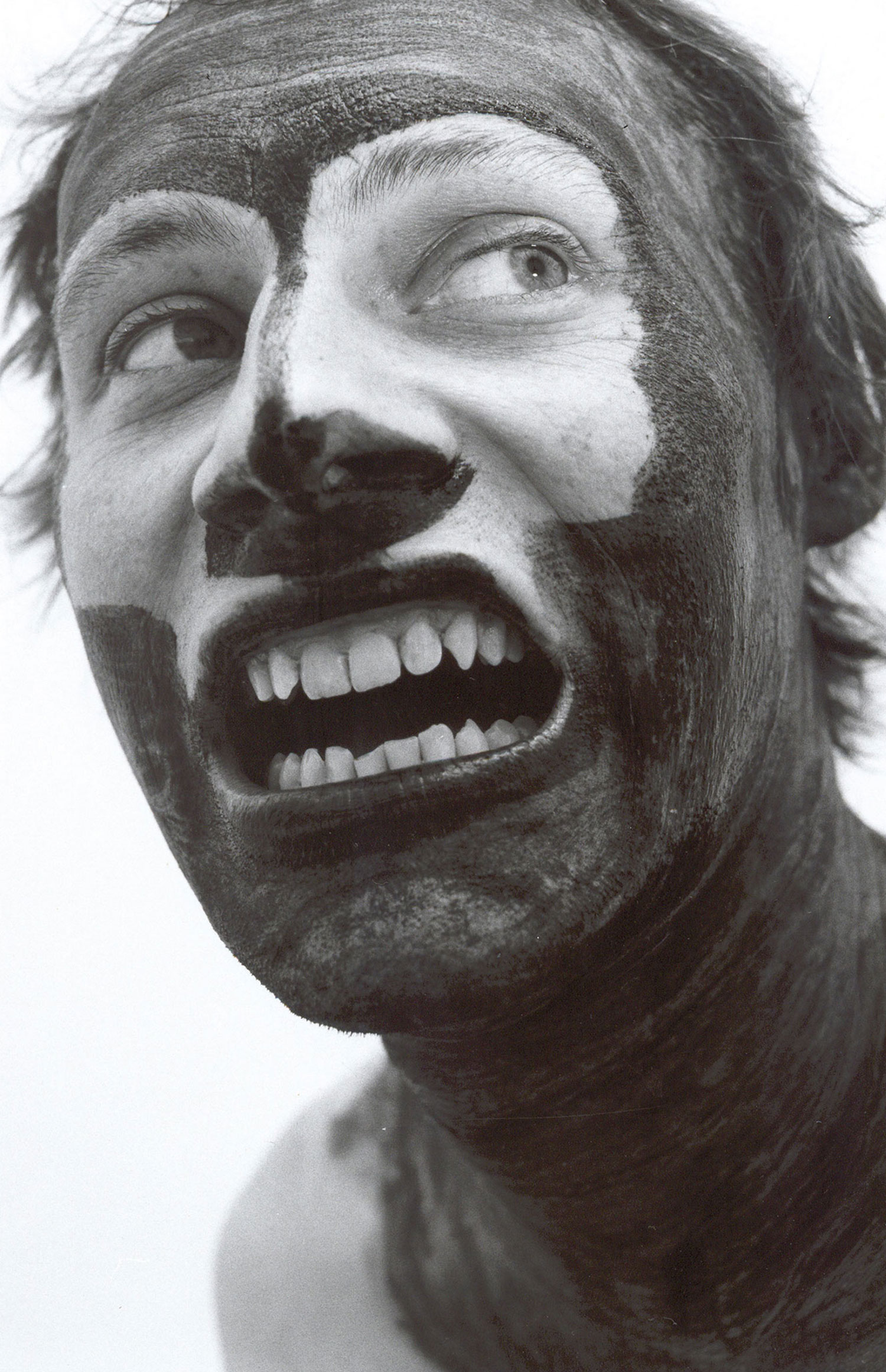

He also played intensely with the idea of inventing himself as an artist, taking on the name of the boxing promoter Blinky Palermo, after Beuys (at least that’s what the rumor says) recognized that he bore some resemblance to the well-known mafioso. His real name was Peter Schwarze, but he was adopted not long after his birth in Leipzig in 1943 and registered Peter Heisterkamp. In 1962, at the age of eighteen, he applied to the Art Academy in Düsseldorf, and after two years of painting he decided to study under Joseph Beuys, although his own work is in many aspects antagonistic to that of his charismatic teacher. Unlike Beuys — who fetishized organic materials such as fat and beeswax and reanimated Nordic animist myths — Palermo’s art is deeply rooted in the everyday aesthetics of postwar Western Germany.

Thinking of his artist friends, who all became more than well-known painters, it is important to note that Palermo too connected directly with the tradition of painting, although he hardly ever used a canvas. As a twenty-year-old he broke down a famous Kasimir Malevich motif into a new composition, which became significant for his own future work. Komposition mit acht roten Rechtecken [Composition with eight red right angles] from 1964 features brightly colored rectangles that glide over a white ground like kites. The paradigmatic rectangularity of the Malevich painting falls into pieces that appear to be scattered at random.

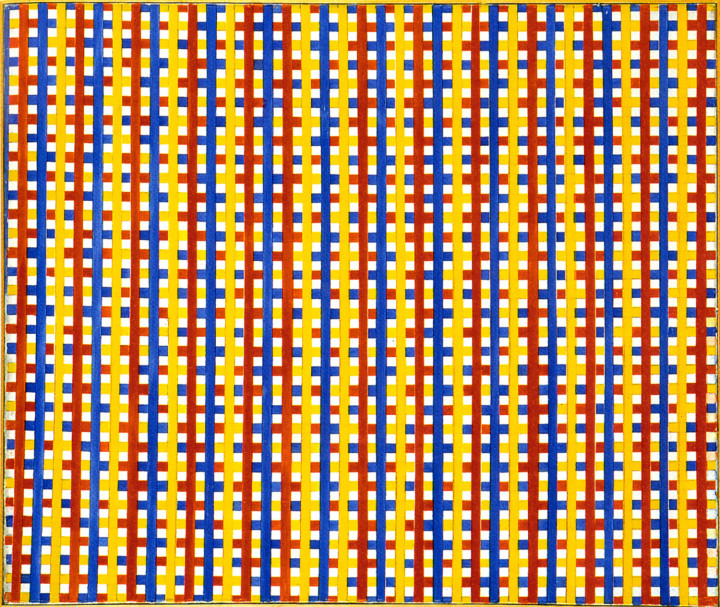

Only a few months later Palermo looked for entirely new formats beyond the painted surface. Material became a replacement for figuration, embodying the very idea of abstract being in its physical presence. Pictures became objects, and objects obtained picture-status. Palermo translated abstraction and minimalism into his very own formal language that defied categorization or ideological sequestration. His Stoffbilder [cloth pictures], originated between 1966 and 1972, combine the principles of picture and sculptural object, as the painterly quality is transformed into colorful textiles. Many of them have the color tunings and internal divisions we associate with Ellsworth Kelly or the late works of Rothko, but basically they are just cotton fabrics from a local department store sewn together into a horizontal composition. Their colors are very ’60s style: dark saturated blue, bright orange, pale pink. Palermo transformed the funky fashion fabrics of his time into great modernist paintings, highlighting one color by means of the other. The lengths of fabric, sewn together and drawn over stretchers, form a flat physical body before the wall that spontaneously generates vibrancy. Color becomes energy, a more intense reality than the material given. From reproductions it is hard to get the idea that these paintings lack real paint. Even when confronted with the original, you have to take a close look to notice the fine distinctions and details that are so important in Palermo’s art. Ellsworth Kelly’s compositions have a self-confident appearance, whereas Palermo’s cloth pictures seem rather fragile, almost insubstantial. As a whole they have material substance, but as a colorful conjunction they appear almost intangible.

This ambivalent materiality is somehow specific to Palermo’s entire work, which is characterized less by formal artistic conceptuality than by an aesthetic mode of thinking. It affects us emotionally in spite of its rather detached form. Titles like Schmetterling [Butterfly] or Leisesprecher [Quiet Speaker] suggest delicate references to reality — a floating on the wall or a dampening of sound. Leisesprecher is a red cloth that hangs unstretched above a smaller canvas stretched with the same material. It is a carefully tuned field of color and shape. Other titles of works are just as objective: Grey Disc, Blue Disc and Stick, Green Triangle, but here too the descriptive collides with the energetic potential inherent in these sculptural works over and above their concrete being. There are small triangular paintings on wood designed to sit over doorway lintels and bricolaged pieces incised and marked with paint. These forms are neither geometric nor organic. They re-enact the well-known gestures of modernism, but keep a handmade look that avoids a too perfect technical look. Carefully positioned in the space, and referring to human proportions, they divide the walls into rhythmic units. In Blaue Scheibe und Stab [Blue Disc and Stick], a tall vertical stick of timber and a small wooden disc, both wrapped in bright blue plastic tape, lean casually against the wall. It works as an exclamation point: “Look at me!” — a striking example of Palermo’s ongoing preoccupation with concerns of form and their architectural and spatial affinities.

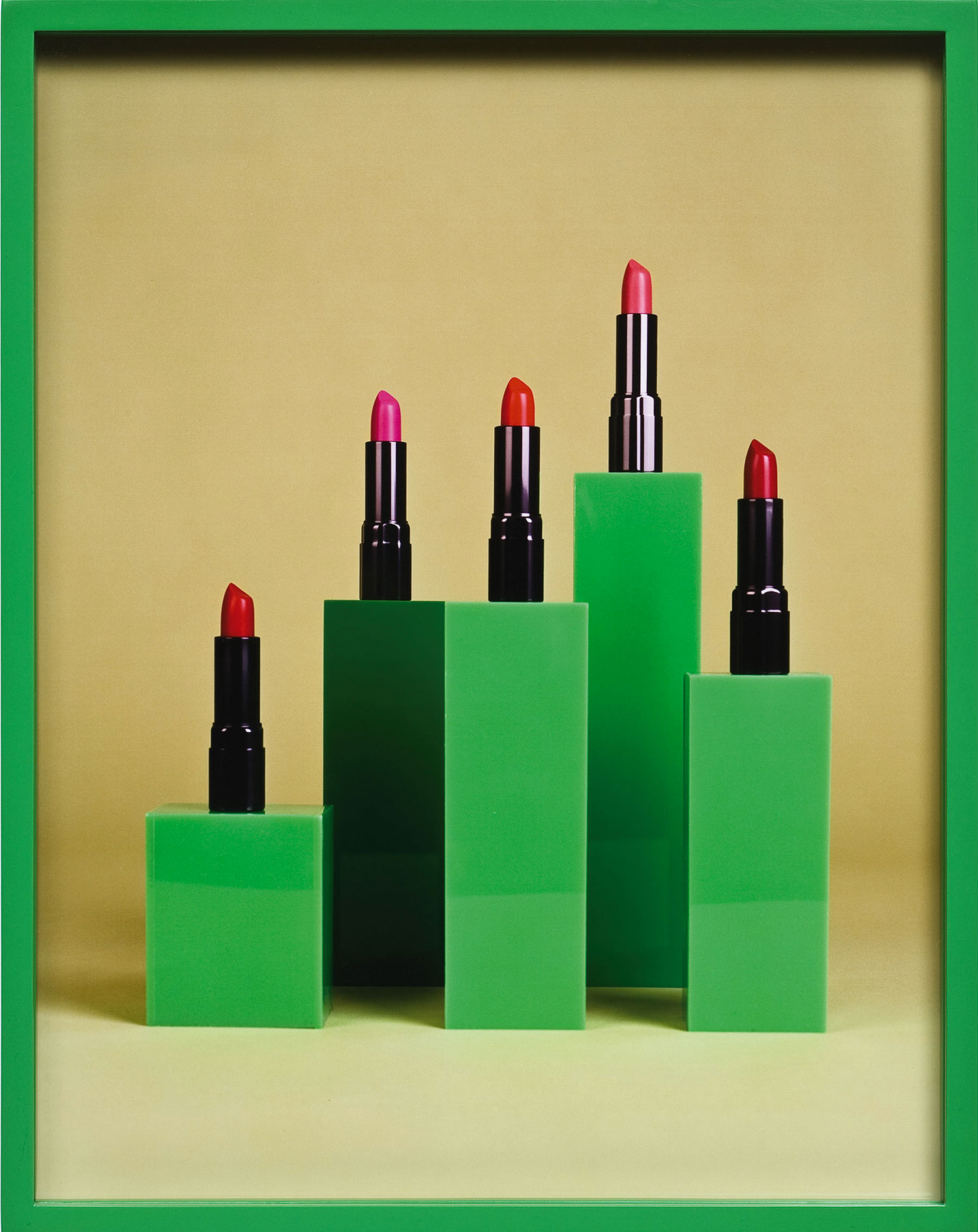

The metal paintings that originated in the US contain explicit references to time or place — Coney Island, Wooster Street, Times of the Day — and are in turn bound up with the sequential form of these compositions. Palermo lived in New York for about two and a half years, from 1973 to 1976. His reasons for moving there were manifold: his serious interest in American postwar art, specifically Newman and Rothko, his love for jazz music and his search for artistic inspiration. The small acrylic paintings on aluminum he produced in New York come in a serial format and strive for an emphasis on the object-like quality of the individual components. They seem to be a result of his introduction to, and confrontation with, American minimalist painting; color is used as a structural component. The specific object-like quality of the metal paintings results from the many layers of paint Palermo applied to the aluminum plates. The viewer has to move around them because the series can’t be taken in from a single vantage point. If you think of Bruce Nauman and his interest in human scale, the interaction between body and work, you get close to the spirit that characterizes these ‘American works.’

Taking them as the final point in this far-too-short artistic career, it is fascinating to see how Palermo’s art developed, how he started with almost traditional painting and began to make very gestural objects soon after. Then the gesture disappeared, to be replaced by the monochrome of the cloth pictures and the wall paintings, followed by the metal paintings. Palermo himself favored a presentation of his works in terms of these groupings. In his exhibition at the Städtisches Museum Abteiberg in Mönchengladbach in 1973 he showed exclusively objects. In 1974 in the Kunstraum in Munich he presented nothing but drawings. His show at the Städtisches Museum Morsbroich in Leverkusen in 1975 concentrated on prints, whereas his invitation to the São Paulo Biennial in the following year was used to exhibit his metal paintings. He created unities between the works for an exhibition ensemble, which owed much to the respective architectural context. In preparation for the exhibition in Mönchengladbach, Palermo turned up with forty objects from different collections, of which in the end only 13 were hung. These, however, were positioned in a relational structure, thus elevating the walls themselves as a component of the works.

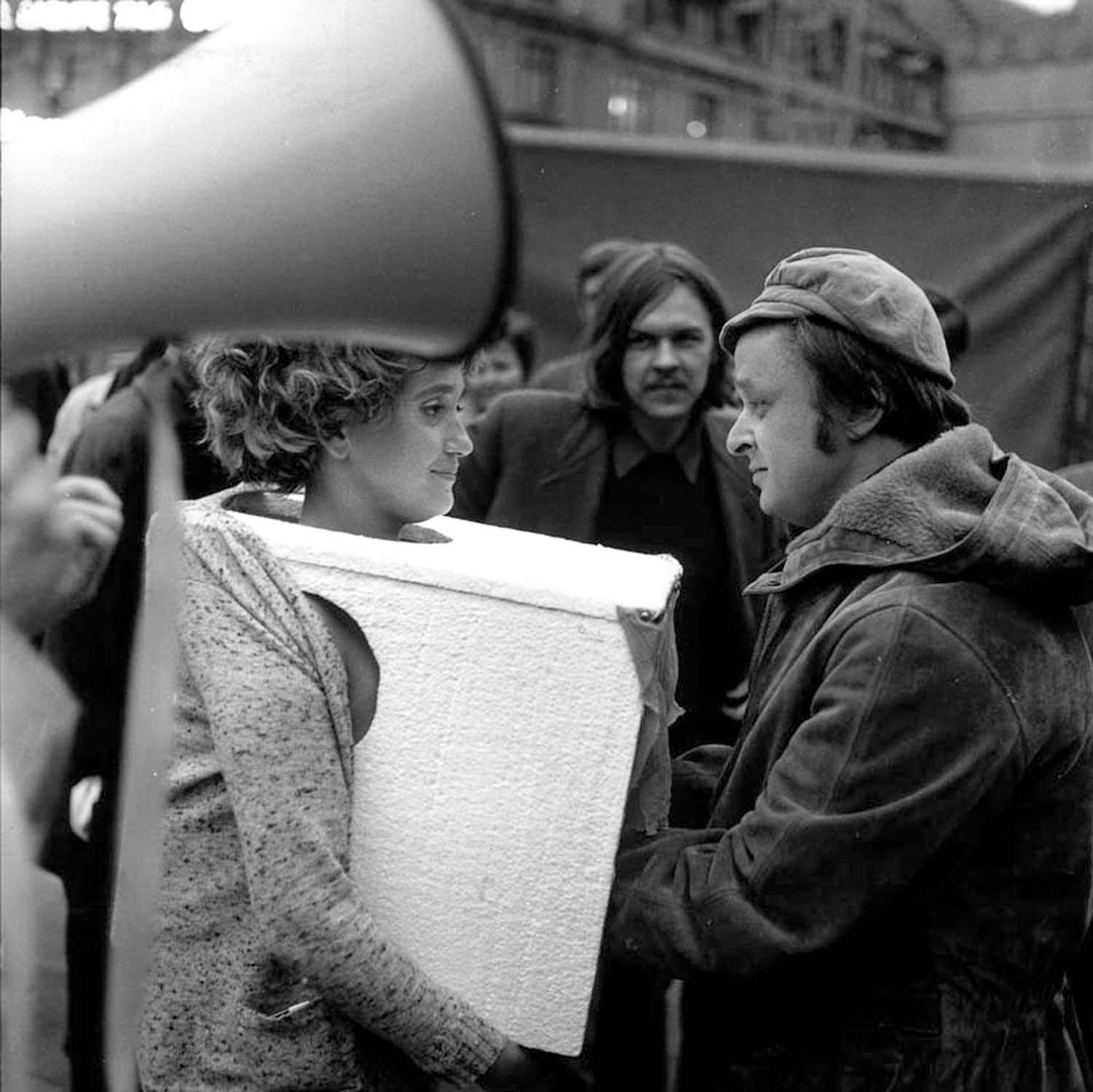

Most striking is the spatial aspect in several of his works which were made directly on the walls of galleries and art institutions, such as the Edinburgh College of Art, where Palermo painted a horizontal band of blue, yellow, white and red running around the architrave of the main staircase of the college on the occasion of the 1970 exhibition “Strategy: Get Arts.” Like most of his ‘in situ’ works, Blue / Yellow / White / Red was painted over shortly after the exhibition closed. In the same year he transferred the pattern of the protective strip from the foot of a wall running up the stairs of an apartment building onto the wall at Konrad Fischer in Düsseldorf. In other works he repeated the outlines of the wall on which he painted, drawing our attention to architectural peculiarities.

Via references to the urban context, he thus reintroduced real space as a dimension of the composition while staying stuck to the surface in a very consistent manner — as if he wanted to test how his works functioned outside the institutional exhibition space. This effect may be somewhat latent in his works for exhibitions, where one is sensitized to identify even Palermo’s interventions that retreat into the texture of the space as such. In the architectural context however, the polyvalence of his spatial art could really unfold.2

Sadly, most of these temporary, site-specific projects don’t exist anymore. But maybe the special quality of these ephemeral projects is actually based on the paradox that the work’s impact is intensified by the limitation of the duration of its existence. “It’s not captured by photos, it remains only in the memories of those who actually stood inside it,” Palermo said of his wall drawings and wall paintings.3 In his temporary works, whose aim was to eliminate the idea of time as a transitory entity, the driving force was indeed the combination of presence and absence. And perhaps these temporary projects clearly manifest Palermo’s progressive ideas about painting after the death of traditional painting.