The purpose of this text is to investigate recent work by five artists embedded in the Mexican contemporary art scenes — a term I purposefully use in the plural since it would be an obvious error to approach the topic as a single instance, even indirectly, something that is taking place at a national level. If there’s anything that characterizes the contemporary art world in Mexico now it is a pluralism of artistic manifestations, communities and circles. Perhaps the choice of works that this piece examines will reveal some shared ground vis-à-vis the use of the object, sculptural construction, and the use of installation in its broadest sense, as well as the way in which the specific works establish dialogues with Henri Bergson’s studies on the concept of duration. However, I’m less concerned with establishing relationships and reading a harmonious discourse between the chosen works than with highlighting each piece’s own remarkable qualities. Mathematic principles declare that the order of parts does not alter a final result, so I will proceed along the lines of handbook etiquette — so, women first.

A few months ago I had the opportunity to visit the studio of Begoña Morales (Lima, Peru, 1977), during which I was able to consider her most recent works: a series of three-dimensional pieces, consisting of different types of tree trunk fragments composed vertically, in which various kinds of apartment models in a neat and modern architectural language have been curiously placed and perimetrically enclosed. At first, my contemplation was brought to a standstill by the strong textural contrast between the various barks against the white, unblemished smoothness of the manufactured objects, as well as by the challenge to distinguish the subtle differences between each of the aforementioned installations. Later, fortunately, questions and doubts about what might be behind and inside these works began to arise. In Begoña’s words, this group of pieces is the result of a study of the iconography of horror films. Then everything became clear — houses without entry or exit, the opacity of their windows and using tree trunks as a natural symbol that record time’s passing, isolation and precarious obfuscation, all here intimately tied together in an attractive game of seduction and fear, as well as, simultaneously and inevitably, linked to the temporality, duration and instantaneity of an extreme feeling. All this is achieved by a simple but effective installation.

Beyond psychology: duration is everything

“Beyond psychology: duration is everything.” With respect to this quotation and what emerges from Morales’ work, I’d now like to delve, however briefly, into the sculptural works of Edgar Orlaineta (Mexico City, 1972). Orlaineta has created an artistic language based on the re-appropriation of modernist furniture. The artist modifies the structure of these everyday objects, adding ornamental plants to them that subsequently become key elements of the composition. A case in point of this is his recent series entitled Jardín Moderno (Modern Garden). Within this strange, ambiguous and lightly ironic environment, the viewer’s perception encounters a comforting breath of air; the artist’s games — I’d even call them formal tricks — are like a sudden chanced-upon sense of renewal. One may appreciate this clearly in Harry, perhaps the most straightforward installation within this modernist Eden. Here, Orlaineta intervenes with something that can now be termed an icon of modernity, The Bertolia Side Chair, designed by Harry Bertolia in 1952. The intervention is signified in an incredibly simple way: the chair has been ripped off its supporting structure, and its back, which now lies on the ground, is topped by a Moon cactus. Avoiding fleeting references to the Duchampian idea of the objet trouvé by presenting an element in constant transformation, Orlaineta confronts a new set of questions around the perception of duration in the sculptural object, in functionalist design and in the relationship between man, nature and architecture. Chair and plant lose their essence and normal character, which inherently sets off unpredictable rhythms, sequences and unsuspected changes.

The universe is durational

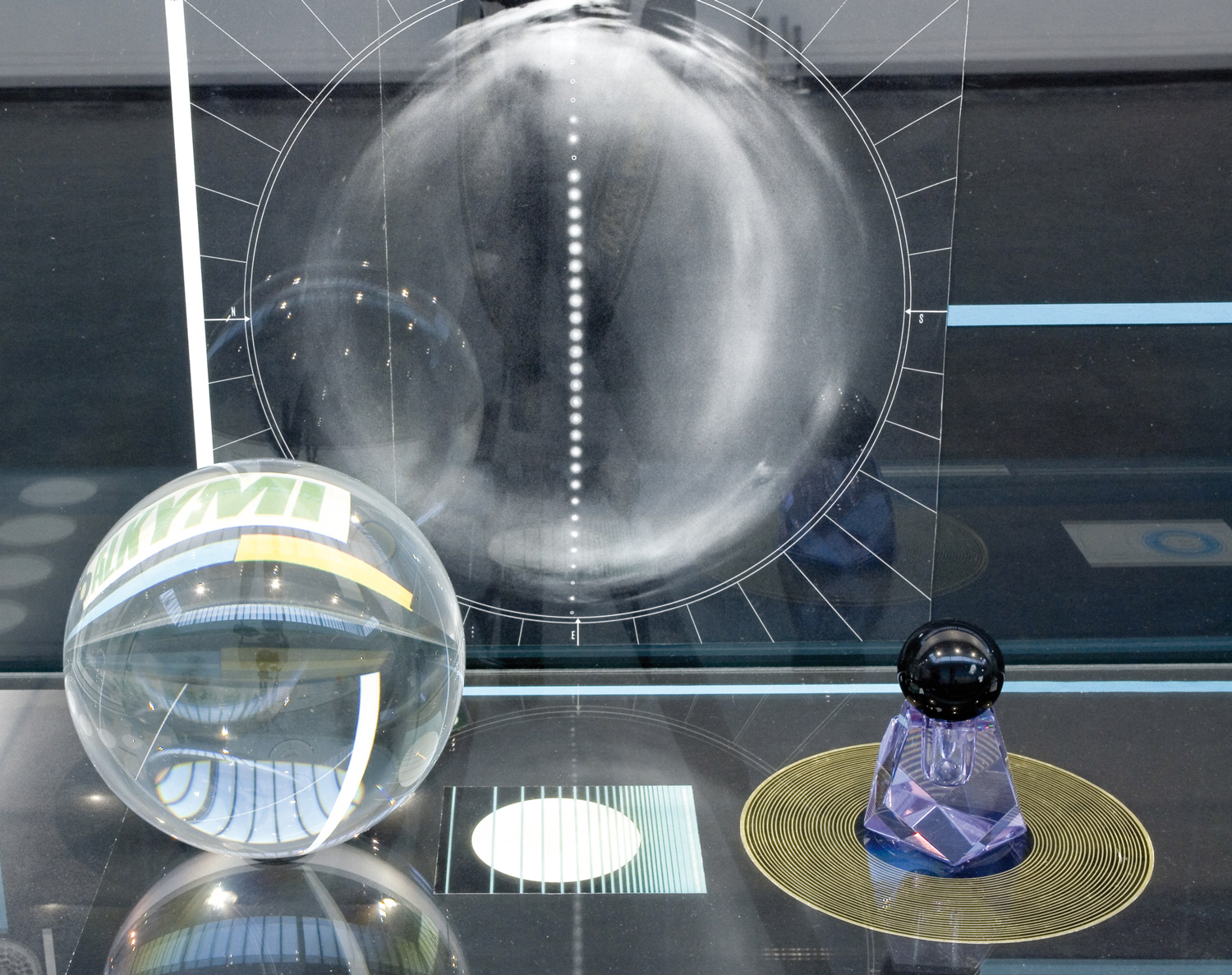

“The deeper we consider the nature of time, the more we will understand that duration means invention, the creation of shapes, continuous making of that which is absolutely new.” Bergson’s thought opens the door rather gracefully to Recital de Piano (Piano recital), 2008, Fernando Ortega’s (Mexico City, 1971) latest project. The artist set off by trying to implement an audio installation including a motorcycle and a piano, both made by Japanese brand Yamaha. Concretely speaking, Ortega’s experiment started off by asking a motorcycle carburetion expert to tune the piano on which the recital would be played to the best of his capacity and auditory education. After this peculiar move, renowned pianist Mauricio Náder would play famous melodies by Frédéric Chopin and Sergei Rachmaninoff for the audience. The result was awe-inspiring. Vagueness, uncertainty and shock involved in this exercise generated an interdisciplinary, suggestive and, at the risk of sounding exaggerated, thoroughly new aesthetic experience. Perhaps Ortega’s first achievement was to limit the motorbike’s presence to a brief series of photographs that documented the process of tuning both objects, placed on top of a pair of tables situated in the room adjacent to the recital space. The motorcycle’s ‘absence’ allowed the piano to softly fill its sonorous, formal character, and to produce a surrogate hybrid that surpassed a strictly auditory, utilitarian or mechanistic air that surrounds the fussy task of tuning and untuning. Ultimately, an interesting dialogue was set up in the professional pianist’s performance in confronting an instrument that is recognizable in form but almost foreign in sound, between the distortion of recognizable (but also new) melodies and the formality and seriousness that characterize classical music concerts. I don’t remember the duration of the recital but I remember that motorcycle and piano were timed in a strange manner.

Can we consider a flying arrow?

“According to Zeno, it is immobile in every moment because it wouldn’t have time to move, that is, to fill at least two successive positions, unless it were allowed two instances, at least.”

In his complex, in-progress project entitled Death at/in Blossom, Sebastian Romo (Mexico City, 1973) deals with various thoughts surrounding an awareness of mortality stemming from Joseph Beuys’ experiences as a Luftwaffe pilot during World War II. Up to now, Romo’s proposal is made up of a large range of drawings and a structural copy in wood of a Ju-87 Stuka, the plane model designed by Ernst Udet that was flown by the German artist. Through this conceit, Romo weaves a contemporary take on ars moriendi in which, once again, the main parts are played by the idea of transformation and dilated instant. A fantastic example of this is Xipetótec (the eviscerator), a drawing in which the artist freezes the moment that an accident took place, the moment of imminent death, with notions of rebirth and fertility which the aforementioned Aztec deity guaranteed through the sacrifice. On the other hand, the scale-reproduction of the airplane is remarkable for its transparency, lightness and lack of any exterior symbols. The machine has been reduced as a skeleton without its skin, a memory, but in the midst of communion with nature. This is a sculpture that has been created to be placed in various environments or public spaces. Its debut will be within the framework of Arco 08, in downtown Madrid’s Sánchez Bustillo square.

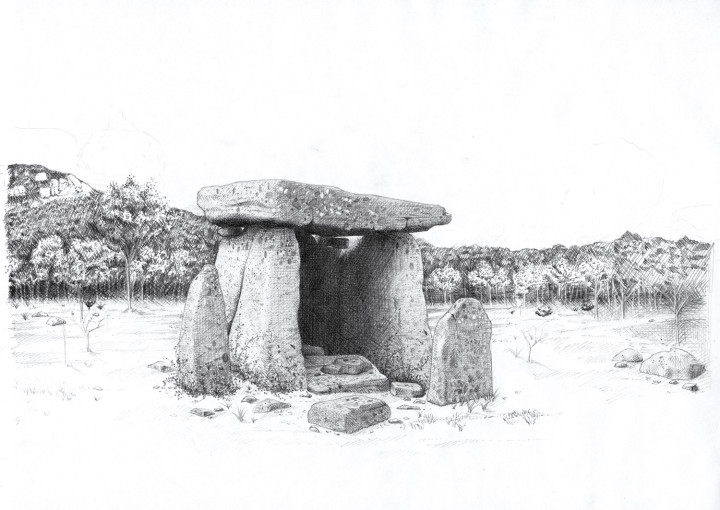

Duration is the continuous progress of the past

“Duration is the continuous progress of the past, corrupting the future and becoming bloated as it advances.” Lastly, I’ll briefly mention Jorge Satorre’s (Mexico City, 1979) most recent work. His project, still in progress, was started during the artist’s short residency in Corsica. After gaining an understanding of the peculiar socio-political context of this area and accepting that it would be an impossible thing to comprehend it fully in such a short period of time, Satorre focused his attention on a megalithic monument that is over five thousand years old. The first stage of the project involved making a precise copy of this dolmen out of paper and cardboard, and to then place the new construction next to the ancient stones. The next stage would depend on what this action would provoke in anyone visiting the site over the following few hours. No one dropped by and nothing happened. Thus, and according to his explorations into the concepts of memory, duration, remembrance and the fate of an act without witnesses, Satorre chose not to keep any kind of on-site documentation. Nevertheless, a few weeks later, he began to create drawings that in a certain, rather immaterial way, describe that which his memory retained of the experience. The work, entitled My Dolmen, puts into play various elements linked to the duration of a gesture, an intervention or a sculptural piece. In this particular instance, the work’s outreach and its duration depend to a large extent on oral transmission. But in the strictest sense, the work only exists in Satorre’s mind.