To experience Bharti Kher’s work is to enter a labyrinth of complex questions based on cultural misinterpretation, social structures and memory. Her works have a language of their own, of which the visual aspect is only a fraction of the overriding narrative. She was born in London and spent most of her childhood in Surrey, a county southeast of England. Her parents emigrated from India as adults; her father worked in a textile company and her mother owned a fabric shop. She was always interested in art, and she went on to study in Middlesex Polytechnic in London and then at Newcastle Polytechnic in Northern England. In 1992 she visited India for the second time; as if predestined, she met and fell in love with her future husband, artist Subodh Gupta, and settled down in New Delhi.

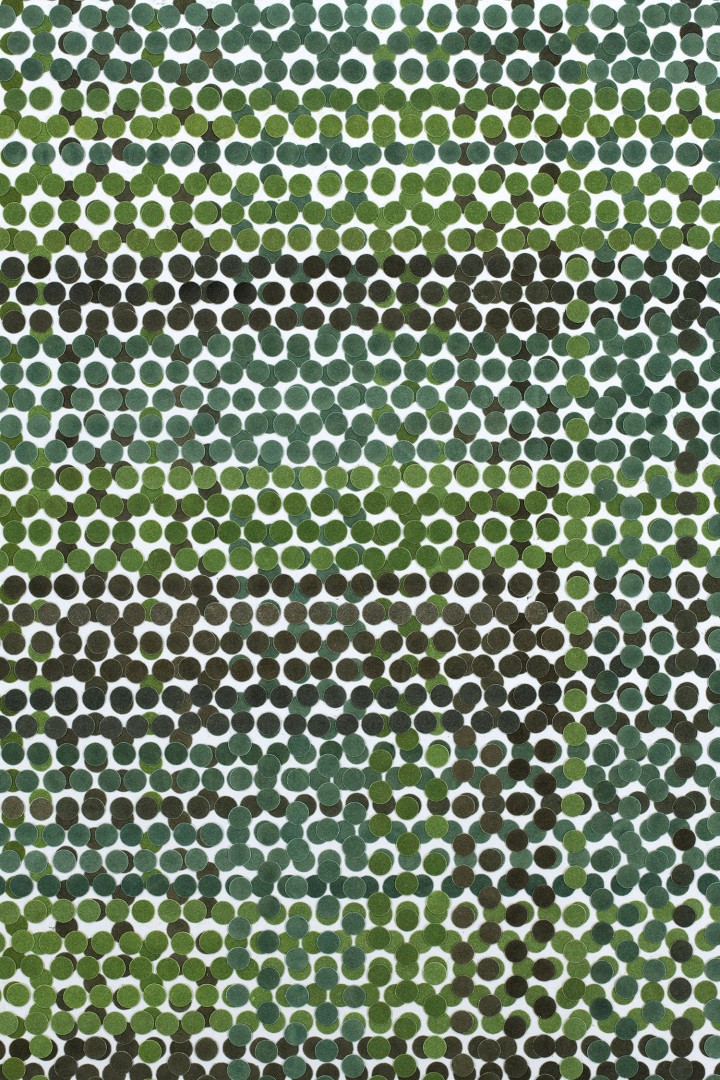

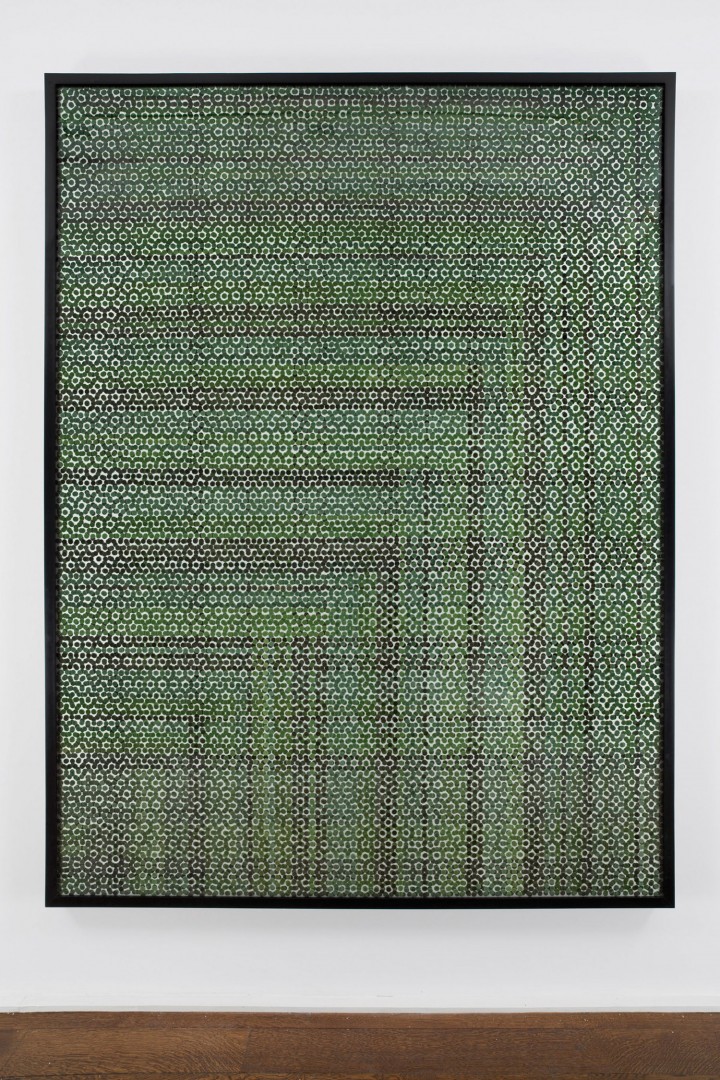

Kher’s works reflect the displaced identity that she experienced back in India. A recurring element of her work is the bindi, a common cultural symbol in India. A female adornment worn on the forehead, it is a Hindu symbol of femininity, fertility or marital status. Meaning essentially “a dot,” it originates in ancient Indian philosophy as a vortex of energy as well as a “third eye” or “all-seeing eye.” The stick-on bindi is a popular cosmetic accessory, which is available everywhere in India. Kher explained in an interview: “In India, when you go to people’s bathrooms, you will see bindis on the mirror, because women take them off and stick them there at the end of the day, and that very bindi is the witness of the day and life of this person. It has been everywhere, it has heard everything.” This dimension fascinated Kher. The bindi, of various sizes, shapes and colors, became an integral part of her works as a tactile surface on large-scale sculptures and “mirror paintings.”

Arione (2004) is the disquieting figure of a dark-skinned, bare-chested woman in leather hot pants and an empty leather gun holster around her shoulders. She stands casually with one hand on her hip and the other hand holding a tray with two pink-creamed muffins. The viewer’s uneasiness grows as the gaze moves from the torso to the legs. With one well-toned leg wearing a pretty pink Mary Jane heel, the other leg is most unexpectedly a horses’ hoof. This sculpture led to Arione’s Sister (2006), a cyborg-like pale white bald-headed woman in a short skirt. Shopping bags fill her hands all the way from her wrists to her underarms, creating a fan-like halo around her, which almost makes her look celestial. “The bags weigh her down, but they’re wings and she’s going to fly…” explains the artist. These polymorphous sculptures represent limitations and contradictions related to the roles that women are expected as well as forced to perform in existing societies. Over the next few years, Kher created even more complex sculptures such as Warrior with Cloak and Shield (2008), a well-endowed, almost naked woman with a large banana leaf hung from one shoulder. Emerging from her head are antlers that are “so big that she looks like she is becoming a tree, which in some ways could be considered to be about rejuvenation.” Another labyrinthine work, Choleric, Phlegmatic, Melancholy, Sanguine (2010), is a heavy bronze sculpture that is on display in Southwood Garden at St. James Church in London. Torsos of three women emerge from a burly mountain-like base, with sea-conch like masks embellishing the foreheads and long snake like arms that circle around the sculpture. Another woman, stabbed in the torso by one of the arms, is suspended horizontally as if lifeless. Here, she expresses a manifestation of the Indian goddess Kali, whose wrath obliterates all evil that exists in the form of ego and desire. An intense dialogue with the ancient and modern, this work conveys a sense of quiet contemplation and dark beauty.

Bharti Kher’s works are enigmatic in nature. There are riddles to be solved and nuances to be interpreted. One of her larger sculptures, Confess (2009), is a wooden confession box that seems to be taken from old church. Calm and serene from the outside, on the inside it is effervescent with countless bindis that are stuck onto the inner walls like an explosion of color. Once inside, there is barely any recollection of what was on the outside; the viewer is immediately transported into a world of fantasy. Like other works, there is a certain claustrophobic uneasiness that fluctuates between truth and lies, reality and dreams.

Her solo exhibition in Hauser & Wirth in New York in March 2012, titled “The Hot Winds That Blow from the East,” was based on the idea of domesticity and home, a space where the self as well as objects take on a different meaning. Bharti explains, “In Asia and India, the house and domestic space constitute a female domain, and this is where women are able to truly assert more ‘self’ within space. But a house is also fraught with social, economic and sexual excesses that can obscure or even threaten to obliterate the spiritual connections that are our greatest resource.” As you entered the gallery space, there was a 17-foot-long staircase, a found object from an old house, installed in the middle of the room, spanning from floor to ceiling — an object of utility and yet of no use. The staircase was stained with red paint and covered with black, sperm-shaped bindis. “I am always interested in the idea of a home. You start your life in a home, and I wanted to explore that but in a way that’s not completely familiar…”

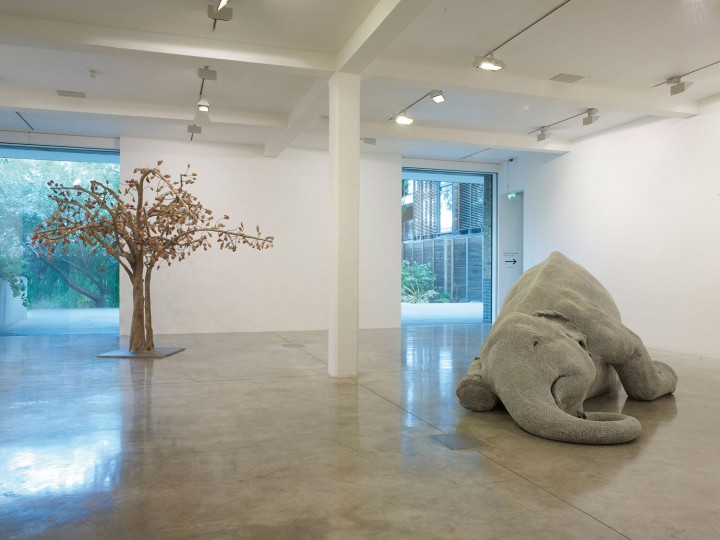

There is a fine thread that connects each of Bharti’s works. Visually, they seem to have no literal relationship, but it is the basic ideology of the artist’s oeuvre that eventually deciphers the narrative of each work. “I take things from books, sci-fi, cartoons, Hindi comic books and even TV. I look at everything.” An Absence of an Assignable Cause (2007) is a life-sized sculpture of the heart of a blue whale, (approximately the size of a small car) the largest living mammal on earth. The sculpture is intricately covered with bindis, and emphasizes the romantic idea of a ‘big heart’, along with the mysteries that bind the heart to concepts of love, life and death. Here she conquers the ambivalence of the imagination with the specificity of reality. The Solarium Series (2007) and its sequel, The Waq Tree (2009), are installations of fiberglass trees bearing what appear to be fruit; these are in fact minuscule heads of beasts, animals and mythological creatures made of flesh-colored wax. There is an implicit reference to the mythic “tree of life” in this work. However, there is also a related legend based on Alexander the Great, who was warned by the tree not to invade Iran. The WaqWaq Tree, as it is called, is believed to be an oracular tree: the heads spoke words of advice to travelers and warriors.

Bharti Kher’s works can be taken as light-heartedly as they can be taken seriously. They are interactive works, both on an emotional and experiential level, that have an undeniable ingredient of seductive beauty married to the grotesque. They captivate audiences, who are hypnotically drawn from a distance to look at the work from up close, where they often inspire curiosity, shock and sometimes even a hint of repulsion.