Recent works by Egyptian artist Basim Magdy (b. 1977), his films in particular, put me in the mind of Zaat (1992), a novel by Egyptian writer Sonallah Ibrahim, a sharp and darkly humorous narrator of his country’s social and political history.

Zaat is the novel’s female protagonist; Zaat means identity, essence, Zaat is the embodiment of Egypt’s drive to survive. The theme is revealed through a dialogue between an inner self and its dreams and an outside world dominated by a carnival of rhetoric, centralized through modes of transmission such as public television (ironically, the book has been translated into a TV series) and speeches that mask governmental policies and their corruption. In both Magdy’s work and Ibrahim’s novel the myths of progress, social and economical development, and modernization seem more a fata morgana effect than a concrete or in any way possible achievement. Talking with Magdy about his work, I began to realize that my cynical reading is actually meant to render a pragmatic understanding of the present.

In his film My Father Looks for an Honest City (2010) we observe a landscape of abandoned constructions in a desert-like environment, accompanied by a displacing sound of rain. A man searches for something undefined in a calm state of reverie, within an unfinished vision of growth, where promises have faded away, or simply were never really there. What could be the beginning of a hallucinatory state develops into an epiphany of melancholic associations in A Film about the Way Things Are (2010). Here, a self-reflexive letter imbued with memories and wishes for the future accompanies images and a vocal narrative. Literal and linear relations are lost in exchange for poetic affiliation and subtly suggested references. Reality appears as a system of erratic occurrences with no rationale or logic governing the terrible beauty of life. Images exist without a direct referent to precise places or moments in time, assembled instead by a dancing parade of emotions, where the cognitive process is married to the expression and stimulation of feelings.

In Crystal Ball (2013) we observe the gliding of fragmentary and overlapping black-and-white images rendered mysterious and spectral by their texture and accompanying soundtrack. Events are in the details, the artist tells us; memory is shaped by things that have no evident significance. As the title suggests, it is an image of the future that we submit to, emptied out of any major achievement or disaster, but composed of exactly those same details that form our portrayal of the past and our experience of the present. Every Subtle Gesture (2012) is an ongoing work in which photographs, taken by the artist over several years of travel, are framed (visually and contextually) by accompanying phrases that become poetic and affective suggestions. The difficult task of finding sense in fragmentary layers and elements is a matter of decisive acceptance; it is an active gesture, in thought.

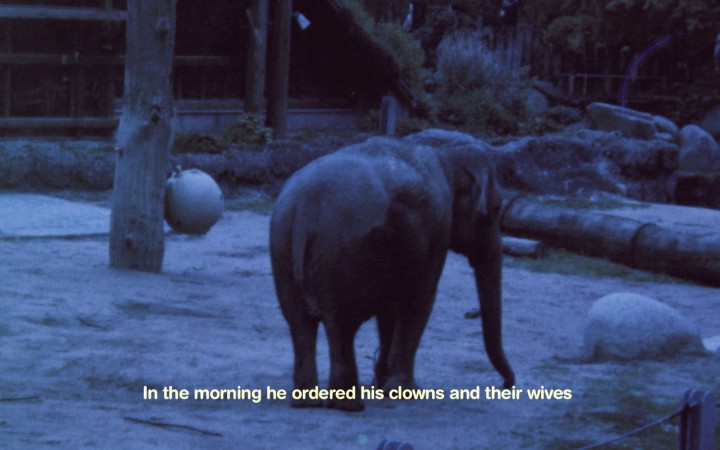

I stop and linger over The Dent (2014), Magdy’s latest film, realized in 16mm. The work bears traces of most of his previous films. It’s worth mentioning that it was commissioned by the prestigious Abraaj Group Art Prize in 2014 and unveiled in in March of the same year during Art Dubai, along the works of the other winners Abbas Akhavan and Kamrooz Aram, Bouchra Khalili and Anup Mathew Thomas. Indeed, it is the artist’s biggest production to date, probably facilitated by the considerable economic support the prize entails. I read that it was shot between Paris, New York, Brussels, Quebec, Basel, Madeira, Prague and Venice, and yet, as generally in his practice, geographical locations aren’t really recognizable — they lose their specificities. Instead they evoke any place and any modern or even future time. This sense is enhanced by the uncanny effect of his image manipulations that, significantly, are obtained via a range of apparently domestic methods, such as exposing rolls of film to vinegar. The manipulation is also aural, as sound is another form of conscious narrative displacement, creating tension through both ambient noises and recognizable soundtracks (such as ABBA’s SOS) that dissolve and reappear throughout the film. A somewhat literary story is told via subtitles in Magdy’s unique imaginative and sensitively emotional style of expression. The story is one of failure and impossible success that starts with the will of a town to host the Olympics, to achieve the international recognition and touristic fame desired by so many cities around the globe. But this ambition is soon transformed into a dangerous collective delusion, and the mayor of the city resorts to hypnosis in order to rescue his population. Nostalgia for the time of hope prevails, yet despite the awareness of past man-made disasters the same mistakes are repeated over and over again. Near the end, a close-up of the face of a sick circus elephant is juxtaposed with the text: “It all started with a dent that hung like a ghost.” Desires have quickly become memories, and achievement is simply not part of this equation. I resort to and paraphrase Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities (1972) when I say that the fictional town of The Dent — and more generally the sibylline visions in Magdy’s artworks — are made of desires and fears, and speak of the secret discourses, the incongruous rules and the deceptive perspectives that animate our life. The voicing of our time is paramount in Magdy’s practice: a sense of revolution that is revolving, not imbued in a sense of failure but in a different understanding of hope.