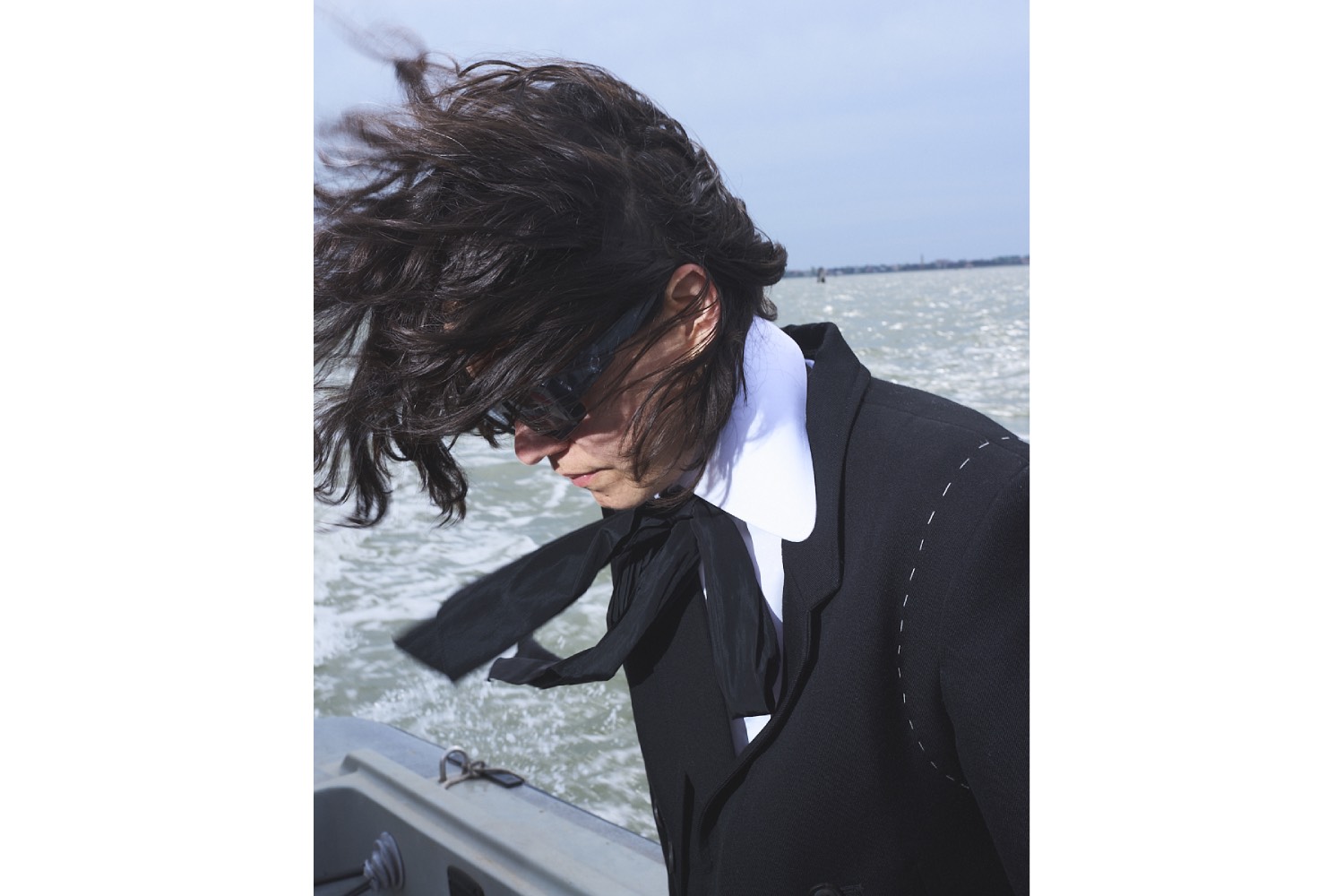

Engineering school in Mexico, tailoring school in Florence, an apprenticeship with fashion designer Bernhard Willhelm in California, followed by the launch of his own namesake collection, which consistently featured exquisite, subversive visions of masculinity that brought him international notoriety — this remarkable trajectory was Bárbara Sánchez-Kane’s unusual path to representing Mexico in this year’s Venice Biennale.

From a young age, Sánchez-Kane was captivated by how the church and the military — two pillars of Mexican society — wield clothing as a tool of power. This obsession drove him to become a menswear designer. Since launching Bárbara Sánchez-Kane in 2016, he has staged runway shows in Mexico City, New York, and Los Angeles, showing collections that dissect and critique contemporary manhood. He considers his fashion designs explorations of the “macho sentimental,” a term that expresses the potential for new forms of masculinity to be understood, accepted, and celebrated.

His bold conceptual curiosity, flamboyant aesthetic, and technical virtuosity caught the attention of Mónica Manzutto and José Kuri. The duo offered him a different context for his creativity. In 2021 he presented his first solo show of art, “Prêt-à-Patria,” at kurimanzutto, Mexico City. Something clicked; Sánchez-Kane, who doesn’t observe traditional boundaries between context and medium, felt at home in the gallery. In 2023 his first solo art exhibition in the US, “New Lexicons of Embodiment,” was held at kurimanzutto, New York.

Sánchez-Kane’s work in the Biennale embodies all of his classic themes. Prêt-à-Patria (2021) is a sculpture and performance that depicts multiple men in altered military uniforms. The front of each garments is untouched, showcasing classic masculine formality, and each is cut away in the back, revealing that under the surface attire they are all wearing red satin teddies, a mainstay of female lingerie. In the sculpture, three soldiers are impaled by a gold pole, frozen ass to mouth forever — exposing these symbols of hyper-masculinity as alpha-submissives to nationalism. From his studio in Mexico City, Sánchez-Kane shares his thoughts on this work and his radical ideas regarding power, gender, Catholicism, nationalism, and how those concepts are embedded in clothing.

Michael Bullock: Prêt-à-Patria embodies the fetishization and subversion for which you have become known. Can you describe what’s happening to the soldiers in your sculpture?

Bárbara Sánchez-Kane: The gold flag pole impaling them is the “Patria,” the homeland shaping their identity. This symbolism shows how nationalism is used to justify certain things, even to tell the story of the Mexican Revolution. The precision and structure inherent in military attire shape the body and evoke a more profound symbolism — a political anatomy of dressage, molding the wearer into a docile body. Clothing transcends its superficial appearance, reflecting the fragmented landscape of societal norms and aspirations.

MB You have always used symbols to analyze and critique power structures?

BSK I’m questioning and, to a certain extent, dissolving what we understand as a “nation” and the Mexican political body, which is usually represented by certain institutions (obsolete, in my opinion) like the state, the army, national symbols, and monuments associated with identity; all recurring tropes in my work. I made eagle sculptures when I started working with bronze. Have you ever analyzed the Mexican flag? In the center is the image of an eagle devouring a snake. We may be the only country whose flag depicts one animal violently eating another.

MB Good point, aggression is at the core of your national identity, although on the flip side I think Mexico is one of the few countries to have artists on its currency. Regardless, you brought the sculpture to life with a performance. Your soldiers, in their provocative altered uniforms, engage in a traditional ceremony known in Mexico as Escolta de Bandera. I read that it’s a militia ritual to safeguard and honor the national flag. What were the reactions?

BSK I noticed some people only understand the very first layer, and that’s how we were taught. We usually don’t go deeper in our knowledge, so they just see a fabric draped over a body. I was at a party, having drinks and talking to an artist, and they told me the sculpture was the most horrible thing they ever saw; he was repulsed by it, and then he returned to it. I love that reaction. Whatever the focus of your interaction with the piece is, it’s fine. Obviously, your mood and circumstances will affect how you view artwork, but to come back to it and have the openness to see it again to see what you may have missed and what a second viewing provokes. I saw a few military men view the piece, and you should’ve seen the faces they gave me; they looked like Francis Bacon’s paintings. I was like, “Fuck.”

MB Do you think they felt you were disrespecting a code of masculinity they subscribe to?

BSK Si, Si, exactly. They didn’t like the new proposed silhouette. I grew up in a very conservative family from the south of Mexico. As a child, the only place I could see performative art was the church or when pledging to the national flag. These are the images I grew up with. All this power, both in the church and the military, was always communicated through uniforms. This is why I’m always thinking about how you can use clothing to open up new possibilities.

MB What about this experience with the church has left the deepest impression?

BSK Catholicism excels at capturing the tension between the mortal and the divine, as well as power, desire, and the complexities of human relationships and existence. Imagine the priest being your secret keeper. Maybe after being absolved in confession, you just change your skin like a snake. “Put on the whole armor of God, that ye may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil.” Ephesians 6:11 is a passage that invites us to resist temptation and to be prepared with prayer and sacrifice for the challenges on earth. Then we see the priest changing chasuble (ornate vestments) colors every season.

MB You’ve always worked between many mediums. It makes sense that the Catholic church was a big influence on the way you work, as it uses every single one of them: painting, sculpture, performance, fashion, writing, and architecture.

BSK Have you ever been to Mexico for the Semana Santa? It’s the most performative tragicomedy — theater as a way of evangelization. Like the lavatorio de pies or viacrucis (Stations of the Cross). When somebody is deceased, you pay respect by wearing black. My grandad was the first person I was close to who passed away; they gave me his suspenders and his ties. Even after their scent disappears, the embodiment process remains the same. I like this process of remembering through the clothing. But then again, in the last exhibition I did at kurimanzutto in New York, “New Lexicons for Embodiment,” I was focused more on the drapery of the clothing: Where does it start, and where does it end?

MB The sculpture with the white fabric that consumes what seems to be a school chair?

BSK Yes, it’s one of my first pieces, and it’s called Lessons in Draping (2023). It’s made from rawhide. In his essay “In Praise of Cosmetics” Charles Baudelaire wrote: “But if one wants to appreciate them properly, fashions should never be considered as dead things; you might just as well admire the tattered old rags hung up, as slack and lifeless as the skin of St. Bartholomew, in an old-clothes dealer’s cupboard.” So, it would be fine for me if the gallery’s sprinkler system were activated during my show, because the sculptures would simply transform since I do not consider them, as Baudelaire says, “dead things.” My work is always in progress; there’s never an end or a beginning. It’s about presenting proposals for a better future. For me, it’s just that.

MB One such proposal is the “macho sentimental.” A concept you have continuously explored in your fashion collections. Who is he? Or she?

BSK Actually, if you read the newspaper, I made it to accompany my New York show, but nobody reads that much; I kind of killed them. That paper announced the passing of the macho sentimental, and it explained a funeral service would be held in their honor; nobody sent flowers.

MB What was the “macho sentimental,” and why is this concept no longer useful to you?

BSK At that point, I was reading Roger Bartra’s book La Jaula De La Melancolia (1987). He argued that we live in a culture that is both macho and sentimental, opposite terms that together define a type of Mexican identity. I guess he was trying to find a way to dismantle these heroic-macho figures that our nation has always celebrated.

MB I see. You have said the military is the pinnacle of toxic masculinity.

BSK If you analyze the evolution of the uniform, its function is to absorb and dissolve each soldier’s individual identity. The soldier becomes merely a disposal body for the government to use. Humans disappear, and they become a reflection of their government’s value system. I was reading “Unbuilding Gender” (2018), an essay by Jack Halberstam on Gordon Matta-Clark; he used suburban homes, very recognizable forms, and he opened these structures up without any regard for structural support. He didn’t know if the building would fall down.

MB Ah, I see the reference. That’s what you’ve done with soldiers’ uniforms.

BSK Si, when you cut where you’re not supposed to cut, maybe the house will fall. I chose to study fashion in Italy at Polimoda because of their tailoring tradition. Tailoring has certain principles; what you don’t see gives garments structure.

MB Even the title of your piece in the Biennale is a reference to tailoring.

BSK My sculpture is called Prêt-à-Patria, because the first prêt-à-porter was the military, mass uniforms for everybody to fight.

MB You’ve said you were raised in such a repressive culture that you didn’t feel like your body was your own until you were twenty-one. How did you take control of your body and start to live life on your terms?

BSK I underwent a few major surgeries before turning twenty-one. When I was preparing for my New York show, I came across this essay by Athina Angelopoulou titled “A Surgery Issue: Cutting through the Architectural Fabric” (2017), which offered me a new queer/trans perspective on that period of healing I went through. It helped me understand that moment of my life differently, as a chance for self-reflection and envisioning a new path forward. That essay gave me a fresh outlook on my scars.

MB Is it too invasive to ask what type of surgeries?

BSK No, it’s fine. I was born with a condition which caused me to faint. From the age of six until I was eight, I would lose consciousness and have no recollection of it afterward. For a long time, I had to take anticonvulsant medication. That was the first thing. Then, after that, I underwent breast surgery. Then, around twelve, there was surgery on my large intestine. My last surgery was for ovarian cancer when I turned twenty-one.

MB That sounds incredibly traumatic. How did all this shape your perspective?

BSK I had one big surgery after another, and then I was like, “Okay, this is not what I want.” That article made me realize that the time I spent healing was a time for me to understand that I could be something else. These experiences made me see my body differently, opening me up to new ways of seeing everything.

MB Growing up, how did you identify?

BSK I was kind of asleep, I guess. Heterosexuality was the first thing offered to me. I didn’t even think about it. The first time a woman touched my shoulder, I was like, “OH! That feels like something!” I’m very close with my mom, and she is very Catholic. During those years, I had a couple of fallouts with my family. That’s probably why I decided to leave and study fashion in Florence.

MB You first studied engineering. Was that to please your parents?

BSK No, I liked numbers. I was about to study architecture, but then I decided on engineering. Halfway through my degree, I realized I didn’t want to continue. My parents told me I needed to finish it. So, I started taking sewing classes in downtown Mexico City while studying engineering. That helped convince them that I was serious about pursuing fashion.

MB When did you start using “he/him” pronouns?

BSK I guess it’s just a daily thing. I get that everybody has their own way. For me, it’s just that some days I feel a little bit more like a “he,” and some others like a “she.” It’s difficult to draft something with he/she; people are going to get confused. Maybe while interviewing me, you see a “she” or a “he,” I don’t know. I’m not going to impose that. Sometimes maybe just being in bed, that’s the only “she” there is.

MB In a Hypebeast video from 2022, you say, “I don’t care if you think I’m a man, it’s okay, I created this person that is me… you see, marketing 101.”

BSK The first time I was doing a runway show in New York and running a casting, a model entered the studio, and I introduced myself. He said, “You’re Sánchez. Where’s Kane?” I think he thought Kane was a gay boy.

MB This reminds me to ask you about Solrac.

BSK My dad’s name is Carlos; Solrac is his name backwards. When I was growing up, I looked very much like my dad. When Solrac, my alter-ego, was born, I was too sensitive about other people’s opinions. I was afraid of what other people could say about me, so I used this alter-ego so I didn’t have to show myself. I started writing under this pseudonym. I don’t consider myself a good writer. Usually, people find it difficult to permit themselves to do things if they are not good at them. They would tell me I was not a good writer, and I would say, “That’s okay. Solrac is going to write,” and I used them just as that, to enter a space I was too afraid of going to myself.

MB Can you read some of Solrac’s writing to me?

BSK We are spectators of the changing seasons

Of the moist of an old tapestry

Of the conventional gestures that we have deserted

Of the scar of the matchstick powder that penetrated my fingertip

Of the pronounced frown that can be the biggest crack for me to cast

Of this collapsed room that we stroll

Maybe we should enact them on a stage

Make it into a play

MB If you were to articulate a better way for society to handle gender, what would it look like? Maybe it’s not even possible to answer.

BSK I will answer with something I saw yesterday. It’s an animation from 1979 called Asparagus by Suzan Pitt.

MB I’m intrigued. Let’s end with Asparagus. Thank You.