Maurizio Cattelan: You produce desire for your audience: How do you generate it? What moves desire?

Virgil Abloh: In general, my criteria for design is that the object needs to be relevant; not just for now, but also for tomorrow. That’s how I measure an idea today. Most importantly, the work needs to tell the story of how as an artist I have rationalized the world. Transparency is a crucial part of my practice. My criteria for making an artwork is expression and emotion. This creates a connection between myself and the work.

If an object is not desirable, I question its reason for existing. It depends on the scale of the output for me. If it’s something made for a personal scale, it abides by less broad rules. If it’s to be mass output at the volume of pop culture, then I have a general recipe.

The General Recipe:

1 part desire, aka a reason for existing

1 part provocation of convention, the unraveling of the accepted facts of the current time period by a new generation

1 part the notion that an everyday object is an art object regardless of the context

Stir with a whisk of minimalism that reduces the sum of all of these parts down to a clear and transparent final product that communicates the process of its creation to the viewer whether they are a tourist (a newcomer to art elitism) or purist (seasoned elitist).

MC: What makes something authentic today?

VA: Authenticity today is something that has roots or origins in a specific past. Contemporary life, as we know it, is largely composed of false advertising that is easy to craft. This is not to say that advertising was not informed by false concepts in the past. It was just less apparent then.

For example, take a look at skateboarding in the ’90s versus skateboarding today.

OR

Take a look at rap in the ’90s versus rap today.

In their origins, these were authentic movements that were rooted in a certain place and time. Today their narratives can be warped. This is not wrong, but hindsight is 20/20. Evolution is as obvious as it is natural.

MC: In a world that runs so fast, how often you feel the urge to regenerate newness? Is this constant regeneration necessary?

VA: Constant regeneration is vital. Like it or not, irrelevance is death. The world has and will continue to operate on a timeline that gets increasingly faster through the handheld spread of information. This is not a fault in itself; it is very much a personal choice to think and operate at that lightning speed. The pace does not care if you join in or not.

MC: We are twenty years past the new millennium. People born in the year 2000 have passed their coming of age: What matters to this new generation?

VA: At this given time in history someone such as myself is inspired simply because I am of a specific generation that has known and understood culture before the internet. Being born in 1980, I was part of the last generation that was pre-internet. Before the internet made all knowledge easily accessible, information was guarded, slow, and very much propped up the gatekeepers and their rulebooks. However, I also witnessed the ’90s culture birthed from the street evolution of graffiti (illegal), hip-hop (virtually illegal), and skateboarding (illegal), all rooted in the idea of taking over public space by the people.

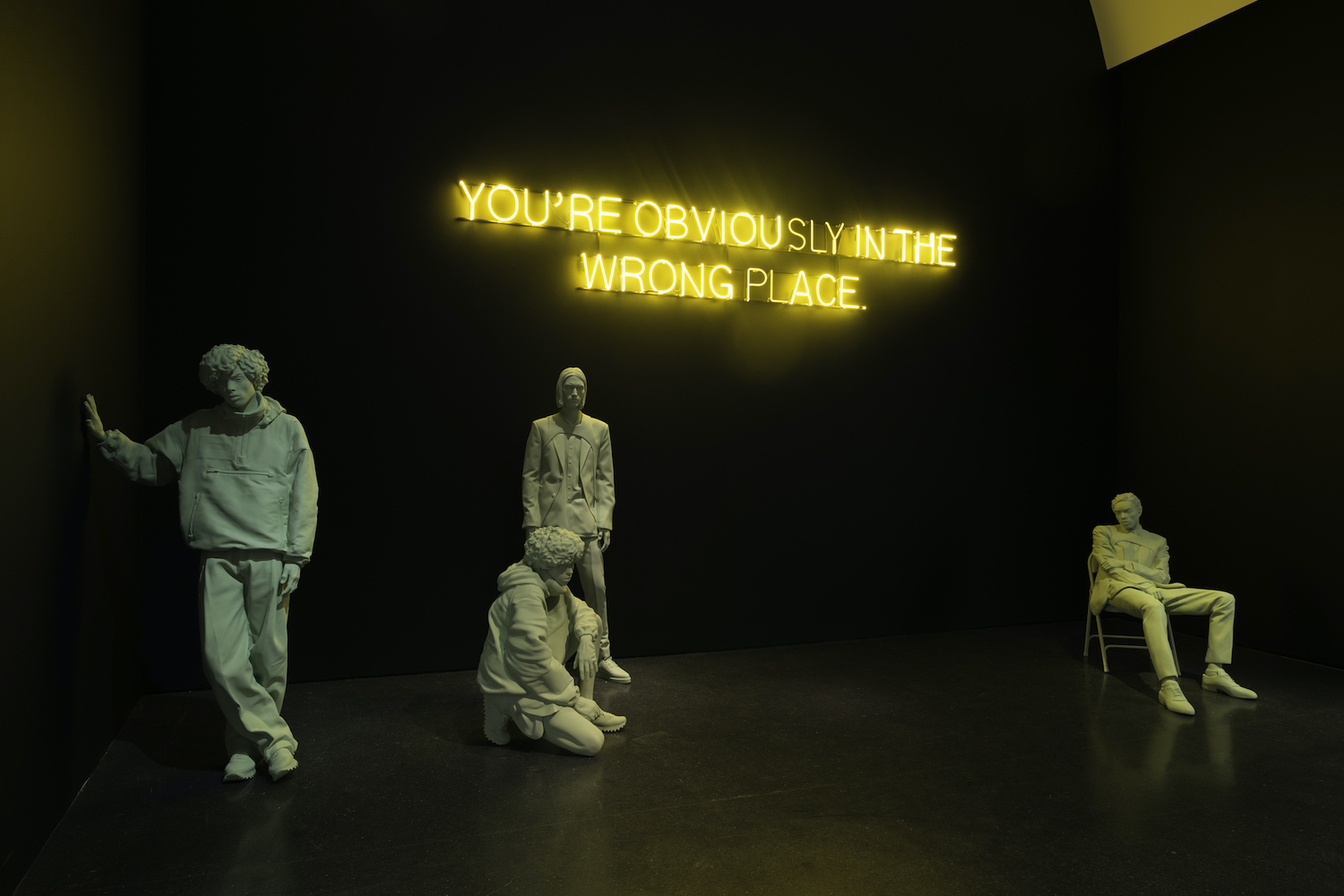

I consider my practice a modern form of graffiti. I try to find ways to have objects be a conduit for what I have to say. For instance, using text on a building in order to craft a dialogue for product design is a part of my general recipe to create the product.

MC: I was thinking recently about the use of an image. An image someone takes from another source changes completely according to the message you want to give. Readapting images for Instagram is a very common trend, even within the art world. Do you think work translated for such a channel has the chance to survive? Does it matter?

VA: I grew up thinking images were fact. I now have the impression that images are like memories. They are slippery and fluid. The context of an image, like with anything else, can alter its message.

Take the Mona Lisa, for example, as an image. I can use that image to call upon all that that image means, then alter it to speak about a larger narrative about high/low, what is real/fake, etc. Facts are all about perspective.

Instagram is a specific moment in time. It is the vehicle for how we as a global community share images. This will inevitably change, but for the moment this is our main channel to share globally. Some of its moral complexities are not the fault of the medium that we use to share. Instead, I think it is how the medium highlights some of our innate human tendencies that is sometimes alarming.

MC: You “copyright copyright” (sometimes). How do you keep your freedom from someone’s copyright?

VA: In my artwork, my main goal is to redefine what we consider to be generic, to operate on the version of the work from the community that designed the original, which can be a murky concept in human history. For example, diagonal lines from the street can become a brand. A way of making and thinking produces an Ikea chair. Conversely, branding the generic is equally interesting to me. This methodology speaks about our now.

My freedom comes from within. As I mentioned earlier, I come from a very specific era and place. I am inherently linked to the time that I was born into, a time rooted in contemporary art and the subcultures of hip-hop, skateboarding, and graffiti. Embedded in these subcultures are the purist notions of foundational thought and tourist notions of vandalism/sampling. Warhol took a Campbell soup can, Duchamp re-contestualized a urinal, Dilla sampled an old soul record, the Supreme box Logo relates to a Barbara Kruger signature, and through these processes, new forms of art were born.

All the artists and work we compare ourselves to have the benefit of hindsight — so I’m more in dialogue with that than with what someone else thinks. The bigger it gets, the more it ruffles feathers… but we all have to remember it’s how the work ages, not how it’s received now…

MC: How do you really protect copyright nowadays? Not only legally but also ethically?

VA: An artist’s job is to be as opposite a lawyer as possible. I am more interested in outputting ideas than wearing the suit of a lawyer while being an artist. Being a catalyst for new ideas and the next generation birthed in the climate of question #6 is more exciting than safeguarding and protecting previous ideas.

MC: Do you have many issues when using images from other sources?

VA: No more issues than any other artist. Although because I do not precisely come from — nor do I look like a typical artist — the ivory towers of art, fashion, etc., I do create some residual noise, but the noise is like jazz music in the background. It actually helps me think of new ideas and provocations based on reactions the work generates: the question of whether something is considered good or bad, what is considered design or not, what is considered art or not, etc.

MC: Are you a logo?

VA: I would consider myself a logic, which would be a tier above a logo. I intentionally, through the severity of specific outputs, crafted a visual language, a way of thinking, and a mode of abstraction. I love the general air of unknowing around my larger practice. It’s my smokescreen. These next years of work are based on extending that language outward from its epicenter.

MC: You are an architect, an engineer, a DJ, a designer, an artist (a renaissance man!): do you always combine all these aspects in your practice?

VA: My art practice is the convergence of all creative disciplines into one matter. I do work in specific mediums at times, depending on the idea, but the practice consists of more than those specific disciplines, which have old-world titles.

I also use my life experiences to inform the work. Often a conversation or a lunch on the side of the road can be most the impactful inspiration of a fashion collection or an artwork, even more than my degrees that I obtained twenty years ago. At times I do appreciate the titles, though; I feel they are stripes I earned. With each title, I aspire to complete every task at the same level.

I’m sure I never told you how I got on this path. Ironically it was during my early days within architecture school that I was told that an architect should be a jack-of-all-trades. That was all I needed to hear. From that point on, I realized that I did not need to ditch my love for Wu-Tang, Green Day, Alien Workshop, and Mies van der Rohe, etc. but could proceed applying them all together.

MC: Fifty years ago McLuhan wrote that “the medium is the message,” but also that the medium is the MASSAGE. Still the same approach today?

VA: Entirely poignant. Marshall McLuhan’s cultural philosophy has had as profound an impact on me as Malevich or Duchamp had on the art canon. In “the medium is the MASSAGE” I can see parallels to the post-hipsterism / “streetwear” meme culture of my generation today — it’s a way to bend the reality that we grew up taking for granted as fact and create a new lasting message that speaks volumes to those than can decode it, or, at the very least, is still substantive to those that can read the communication at a surface level.

In my practice, by design, I think without limits. Messages are meant to be traversed. I refute the idea of placing work in any box. I’m exploring the self-endowed freedom to create. Everyday language, grammar, and my own personal philosophies are equal territory to mine as the art canon. Every medium is equal. This is very much a McLuhan train of thought.

MC: You began working with collaborations since the very beginning: from Murakami to Jenny Holzer. What is the poetic of collaboration?

VA: For me, it is a myth that creative projects exclusively get created in a test tube. Of course, it can be, but equally intriguing to me is creating through conversation. The word collaboration is interchangeable with the word conversation. I have a distinct set of rationales that make up my practice that are deeply personal to me; however, in practice this set of rationales works in collaboration with a brand or an artist in the same way. As a believer in evolution and the breakdown of barriers, I am using my practice to show that art conversations break down barriers: art/not art, high/low, etc.

MC: Pop culture and art matter to more people if they collaborate. Would you agree?

VA: Conversations are more powerful than a gun or a line in the sand. In this new era, I often question the validity of even looking at the period of time when high art and mass culture were kept distinctly separate. The only value that I see in keeping those worlds distinct is providing economic benefit, which is fleeting. The internet has democratized information and equally the need to actually own. If you ask me, it is the Wild West for artists to dictate new modes of operating.

MC: Do you have a “creative exercise”?

VA: Over-intellectualizing the mundane is my creative exercise.

MC: What is an artwork today?

VA: An artwork is a pure idea attached to an existing rationale. An artwork for the art world is any idea attached to an invoice.

The interview itself quite literally is a conversation, but also equally a collaboration. If we decide to write these words in stone or pour them into a bronze plaque, it technically falls into an “artwork” for purists. Leave it as words on the internet; then a “tourist” can find it.

MC: Do you like bananas?

VA: The bananas are a contemporary mirror. To dislike the bananas is like blaming a mirror for its reflective properties. When an artwork moves effortlessly from the tourist pages of the NY Post to the most purist eyes, then you do have a truly unifying moment. Those moments come only when stars align.

MC: Are you carnivorous?

VA: I am what I eat.

MC: Art has been an endless story about hierarchy. My door is always open.

There’s no hierarchy. Is yours?

VA: Same, my door is always open. Hierarchy, again, is the human trait that gives license to absurd human behavior with no cause. If you ask me it is old age; it is useless unless you are hypnotized by the past.

MC: Are you obsessed by the zenith? I am.

VA: I am constantly wondering if the zenith is now. It certainly feels like now. There are so many signs. The way ideas are traveling and multiplying and resonating confirms this thought.

I’m obsessed with the Renaissance. It was the starting point of my course work in art history. As a student, I couldn’t help but draw parallels to our own time since I started my postgraduate degree in architecture.

MC: What if you wake up tomorrow discovering that your work has no more impact?

VA: That will be the day I will pursue my lifelong dream of being a gardener.

MC: I removed this idea that art is somehow detached from the consumer…

VA: Lately, I have been questioning what consumption is. Our generation is rapidly unthreading every notion that generations in the past agreed upon. Questions about the environment, consumerism, value, necessity, health, etc. Plastic is now a curse word. Cigarettes are as taboo as cocaine. Everything is being questioned, which I imagine makes a better time for an artist to introduce new ideas.

MC: Art saved me. Did fashion save you too? Or do you see yourself more a savior?

VA: Fashion was a vehicle for my ideas. When I started, it was the easiest subway train to graffiti without a cop in sight. It is only one communicative device, one soapbox to stand on and speak from. All the arts have value. I can’t imagine not scaling the heights of those that interest me and laying a foundation for future ideas. We have one life to live. It’s the narrative arc of creating work…

MC: Do you think you’re one, among creative people, who has defeated death?

VA: I often refer to a total body of work as “kicking a dent in the world.” My work’s main objective is to interrupt the preexisting timeline of contemporary art by challenging its fundamental principles so that when I’m no longer here, there will be more room to redefine the arts than when I started. That’s my own measure of success. Not self-service but serving the whole instead.

MC: At this point, is there anything to be insecure about? Life is the hard part. Art isn’t.

VA: Exactly. Unraveling life’s man-made myths at the earliest age possible is the hard part. Once one has unraveled the prisons we build around our own minds and abilities, there is true creative freedom. After that the world becomes crystal clear.

MC: What do you like about an image?

VA: Images are flawlessly subjective.

MC: Visibility is almost always a child’s disease. Are you affected by it?

VA: Essentially the Hero’s Journey…

MC: I could do it too. How beautiful is it to say, “I did it”?

VA: How beautiful! Now you can just send the banana emoji in place of any question asked of you for the rest of your life. Now, that is a new kind of contemporary art in my book.