“John Akomfrah […] said something that struck me, because I feel it’s at the core of almost everything that I do. He said that essentially what he tries to do is to take things and put them in some sort of affective proximity to one another. That really hit me because I think for me, in a nutshell, that’s what it really comes down to.”

—Arthur Jafa in conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, 2016.

Arthur Jafa juxtaposes imagery from different contexts in “affective proximity.” His work consists of pictures, sequences of video, and music, which he combines and assembles anew. The artist is a master of sampling. His source materials encompass historical images, portraits, excerpts from documentaries, amateur and viral footage, music videos, TV programs both old and new, films produced by fellow artists, as well as the artist’s own photographs and films. He makes no distinction between pop and high culture, reassembling the material into a unique rendition of African American history that is as complex as it is ambivalent. The affective moment occurs by means of shifts in context, the proximity of imagery opening up spaces for reflection.

“What would America be like, if…”

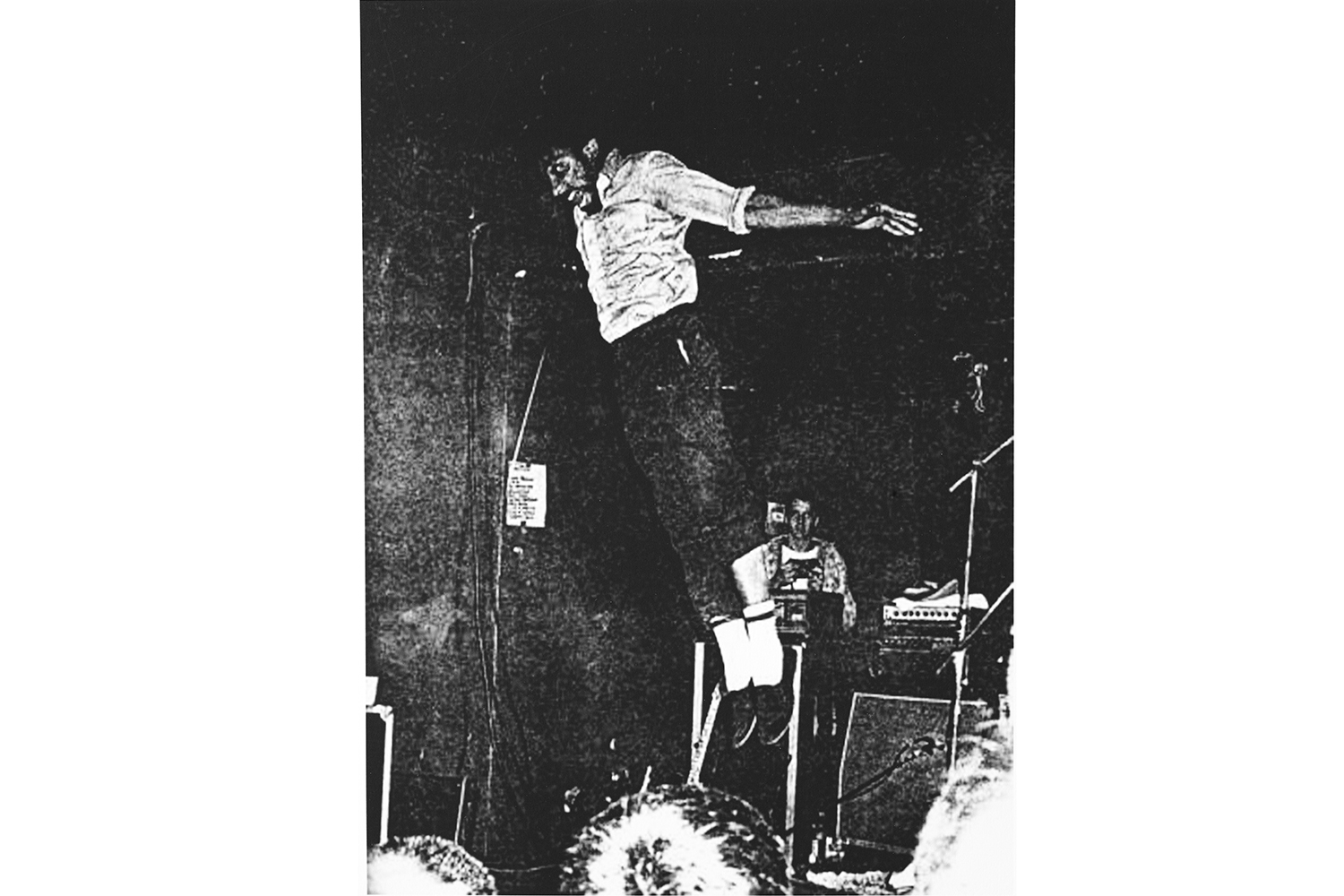

Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016) “is a layered homage to the ’70s club anthem ‘Love Is the Message’ by Philly International’s studio orchestra MFSB, and to the classic short story ‘Love is the Plan the Plan is Death’ by one of Jafa’s most beloved shape shifters, ’70s ‘New Wave’ speculative fiction author James Tiptree,” explains the writer, musician, and producer Greg Tate. The video became Arthur Jafa’s breakthrough, when his friend, filmmaker Kahlil Joseph, screened the video as a prelude to a private film night at Art Basel 2016. Love is the Message, the Message is Death merges found footage into a seven-minute music video capturing the great cultural achievements — together with the extreme pain, bliss, hope, tragedy, and injustice — of black American experience. Glorious moments in history, victories in sport, the freedom of improvised jazz, mutual support and hope through gospel singing, the expressiveness of hip-hop and street dance, but also police violence and racism on the streets: they are all here, as Kanye West’s lyrics to Ultralight Beam, which can be heard on Love is the Message, the Message is Death, state: “This is a God Dream. This is everything […] I’m tryna keep my faith. But I’m looking for more. Somewhere I can feel safe. And end my holy war.” Perhaps “affective proximity” is the route leading there, the way to a place where neither utopia nor dystopia prevails. In the middle of the video, the young actress Amandla Stenberg issues the central question: “What would America be like if we loved black people as much as we love black culture?”

“The Pure and the Damned”

Just as pleasure and pain are linked in Love is the Message, the Message is Death, so are the pure and the damned, love and hate interwoven in The White Album (2018). It was for this video that Jafa won the Golden Lion at the 58th Venice Biennale last year. It gathers together amateur videos of people talking about racism, loading weapons, shooting each other, or hugging lovingly. Jafa combines such imagery with portraits of white people he regards affectionately from his immediate milieu, in an ambivalent portrait of America in general and of his personal experience in particular. The work is unusual within his oeuvre in that it literally creates a dialogue between protagonists from different contexts. The White Album is full of confessions. Not only do the images interact with each other but so do the words: their ambivalence, their force, their aggressiveness. Language is at the heart of racism. In The White Album, both strengths and the dark depths of the human psyche become exposed through language and its freighting. In amateur videos three people talk openly in front of the camera about their views on racism, resulting in a quasi-conversation between them. A white man who is no longer proud of “white America” and is encouraging people to confront their own fears, determinedly states: “We don’t wanna lose power. We don’t wanna lose privileges. We don’t wanna lose benefits in a system of white supremacy that we have created here in America for white people. […] Face your fear. Face your greed. […] Our country is a country of white fucking supremacy. Yes sir, it is. It always has been. Let’s face it.” He explains that institutions, culture, structures, power, psychology, politics, media, education, and history have all been “whitewashed and biased.” Later, another video sequence shows a young white blond woman who self-righteous claims to be “the furthest person from being racist.” Her subsequent statements, however, reveal exactly the opposite, culminating in a demand for respect for white people. There then follows an African American sporting gold fronts who states in an offhand, easy-going manner: “You wanna argue [laughs]. I can’t argue with you. You mad! You big mad [laughs]! I’m happy. Leave me alone. I just want some money. A lot of money. I don’t get paid to argue with you. No. Who is you? You ain’t nobody.” Following this trilogy of self-confessions, a white man appears, repeatedly reloading his rifle. The portraits of close confidants from Arthur Jafa’s milieu, including protagonists from the art scene, some of whom have made a significant contribution to promoting the artist, appear repeatedly. Is this a declaration of love or a comment on the hegemony of a “whitewashed” art market? Maybe both. Close-ups reveal physiognomies in all their detail. The White Album is a video-collage about love and hate. Or, as lyrics by Oneohtrix Point Never suggest at the beginning of the film: “The pure always act from love. The damned always act from love. The truth is an act of love.”

Eight Hundred Images of Absence

There is hardly any other work by Arthur Jafa containing such a quantity of imagery as APEX, his masterpiece from 2013. The eight-minute video includes more than eight hundred images that appear and disappear within seconds to a soundtrack of techno music. It is a rapid slideshow of photographs from cultural memory: pop culture, the history of music, the civil rights movement, scenes of violence, portraits of famous people, physiognomies, but also abstract imagery. Brief video excerpts appear in just two short sections: a scene from Kahlil Joseph’s music video for Flying Lotus, in which Storyboard P dances; and a scene from the motion picture studio TNEG, a film collective, which Jafa co-founded.

“APEX is a meditation, but a hard one, a difficult one,” is how jazz musician Jason Moran succinctly describes the experience of the viewer confronted by this central work in Jafa’s oeuvre. He continues: “And you have to face it. The music demands that you face it, the images in their rapid succession demand that you face it.” In other words, APEX places African American history “in your face.” There is no way to escape this digital collage. The mesmerizing visceral effect of this work arises from the sheer mass of imagery, the extreme speed of the sequences, but also from the volume of the Detroit techno beats, Robert Hood’s track “Minus” (1994) penetrating deeply into the body.

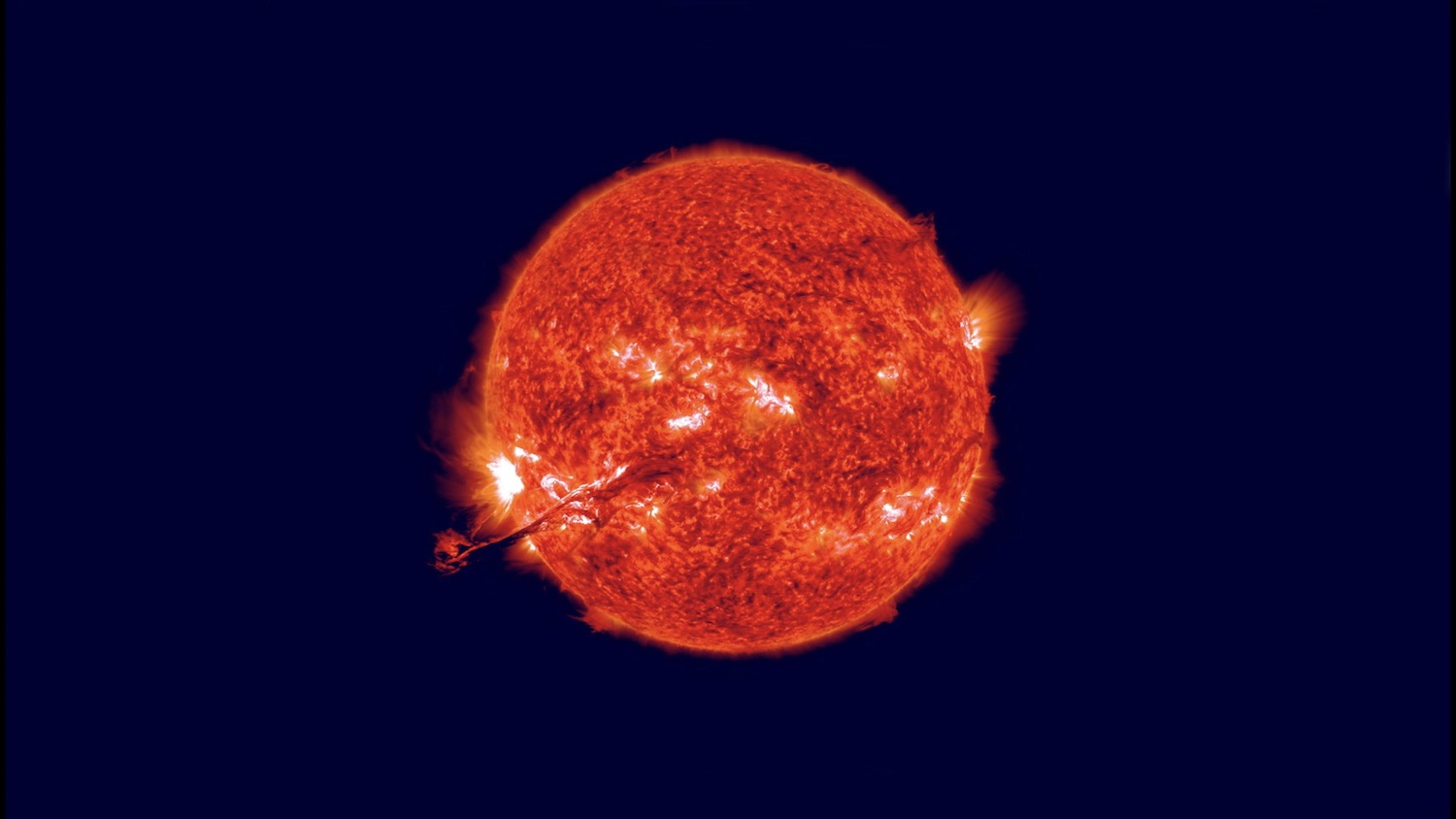

Jafa sees the slight shifts that occur in repetitive dub techno as an expression of absence, a subject central to his work — that is, invisible, repressed history. In APEX, Jafa situates glory and pain, freedom and oppression, the body and physiognomy in “affective proximity.” It is a history of music encompassing such names as Jessye Norman, Albert Ayler, Elvin Jones, Nina Simone, the Geto Boys, Robert Johnson, Michael Jackson, Little Richard, Marian Anderson, Beyoncé, Miles Davis, Kurt Cobain, Rihanna, David Bowie, Whitney Houston, and James Brown, as well as such important figures in African American history as Frederick Douglass and Jonathan Jackson, but also cartoon characters like Mickey Mouse and Krazy Kat, together with images of historical moments and violent events. There are, in between, both micro views that evoke a seeking of origins and macro views that lead to outer space. APEX unfolds hard and cool like a science fiction book. And, in fact, the work does have its origins in books. Arthur Jafa started collecting images in the late 1980s and filing them in his so-called Picture Books. It is these Picture Books that provide the basis of his pictorial cosmos. The idea for the video APEX came about when transferring these analog albums to the digital. The images race before our eyes, too fleeting for all them to be internalized. Consequently, APEX essentially expresses absence, making us think of what Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson describe as “afrotropes.”1 When asked how they understand “the process of formation, disappearance, materialization, and return,” 2 Copeland and Thompson point out: “Afrotropes are […] about the visualization of what is known but cannot be spoken and about that which cannot be seen, enabling black folks to come to terms with loss, longing, and absence.”

A Series of “Afrotropes”

Arthur Jafa’s current exhibition titled “A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions” has been touring Europe for three years.3 The exhibition’s title relates to the sense of absence that Jafa sees haunting black lives. It could be imagined that the show consists of “afrotropes” in Copeland and Thompson’s sense, combining large-scale wallpapered works of historical events, photographs, and Jafa’s mixtapes, with works by other artists. Photographs by Jafa’s mentor Ming Smith and striking collages by Frida Orupabo are likewise part of the exhibition, as are videos by Missylanyus. At each venue, Jafa reinstalled and rearranged how the various elements interacted site-specifically.

The exhibition functions like a walk-in Picture Book, enabling Jafa’s keen filmmaker’s sense of the interplay between imagery and music to emerge within a three-dimensional space. His intention of developing a black cinema entailing “the power, beauty, and alienation of black music” succeeds by assembling images and video sequences in extreme, “affective proximity.” This opens up spaces for unlikely and extraordinary renditions. As Arthur Jafa explains: “It has to do with a certain kind of contextual dissonance. When you place a thing in a context that didn’t generate it, there’s a weird slippage or dissonance that happens, a certain movement.” This results in Jafa managing “to worry the note,” as he expresses it, and in doing so achieve “affective proximity.” The invisible becomes visible.

And you: You have to face it.