Originally published in Flash Art International no. 137 November-December 1987

Among the many histories of Italian art in the sixties, the volume by Germano Celant (1985, Electa) describes the most important stages of arte povera but not the development of each single artist from the beginning on. The book starts with the exhibition “Arte povera-Im spazio” at the Bertesca Gallery in Genoa. (September-October 1967), where some arte povera artists and others of the Roman school – such as Mambor, Mattiacci and Tacchi – were included. The exhibit was held one month before the publication of Celant’s seminal “manifesto” in “Flash Art.” Such a history does not underline Pino Pascali’s role as a link between the generation of artists who semiologically appropriated the contemporary world (Schifano, Angeli, Festa, Manzoni) and the new generation, that is, it does not describe the situation in Rome revolving around Plinio De Martiis and, later on, Fabio Sargentini. Furthermore, the text does not explain the movement’s background in the north, with Pistoletto and Gilardi in Turin.

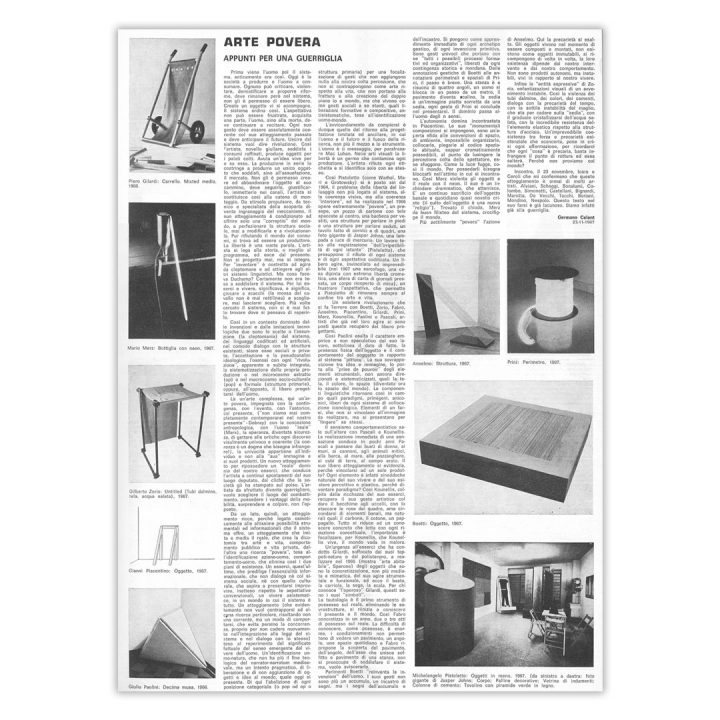

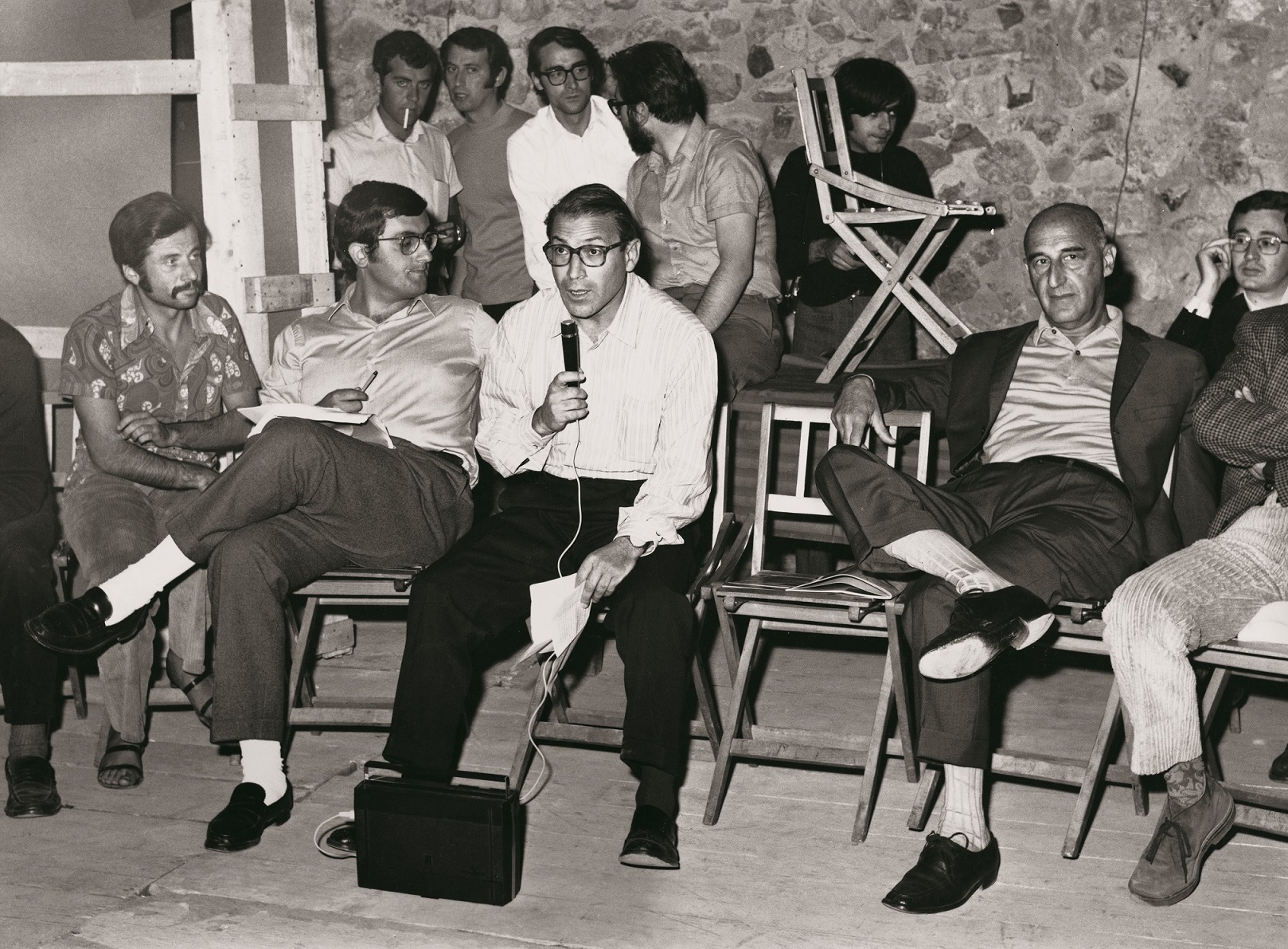

In November 1967, in the fifth issue of “Flash Art,” Celant published “Arte povera: appunti per una guerriglia,” stressing the parallel between a “revolutionary” social situation and a moment of aesthetic rebellion. Kounellis, in an interview published in the same issue, states, “What is important is being free, and this freedom manifests itself concretely in aesthetic shapes.” Celant, too, speaks of freedom, from an alienating rationalistic system, from coherence, from optical art, Pop art and minimalism. He speaks of a “poor” art as opposed to a complex one, of an art that does not add ideas or things to the world, but that discovers what’s already there; an interested in the present, in contingencies and events as a convergence of art and life, somewhat like in Grotowsky’s concept of “poor theater.” Celant refers therefore to an anthropological dimension of authenticity and unalienated labor where man is identified with nature. He refers to Pistoletto’s Oggetti in meno of 1966 (not to the mirrors), to Boetti, Zorio, Fabro, Anselmo, Piacentino, Gilardi (his objects exhibited in 1966 at Sperone, not his polyurethane rugs), Prini, Merz, Kounellis, Paolini, and Pascali. Marisa Merz is not mentioned, nor is Calzolari or Cintoli, but in conclusion, he adds the names of Ceroli, Bignardi, Tacchi, Mondino, Icaro, Simonetti and others. He stresses the empirical character of Paolini’s analysis of the relation between the subject and the system of painting. He stresses Kounellis’ physical presence and acts in the works, such as feeding caged birds or taking black roses off his canvases, therefore aligning him with current developments in authenticity in theater. He speaks of trivial, simple materials which are also natural, such as charcoal, cotton or a live parrot. There are no references yet to the dematerialization of the artwork, which only comes up a year later, when Celant wrote his “Arte povera e azioni povere” text for the Amalfi exhibition in the fall of 1968, published after the event in 1969. As the critic saw it, therefore, arte povera ran a fine line between a liberation from traditional or technological forms of art and a renewed appropriation of the world, immediately opening the way for performance/body art and land art. A split therefore took place between most of the artists and the rushing of art towards novelty, in that throughout the seventies, most of the arte povera artists continued developing their work as installations, while critics began to observe more closely other dematerialized and conceptual forms of art (art as books, video, etc.) Gilardi, on the other hand, actually stopped making “gallery” art in 1969, after having shown with Sonnabend and Castelli, and did not exhibit until very recently, all the while working as an independent social worker with the mentally ill, children and the elderly, somehow falling into a ideological and aesthetic short-circuit.

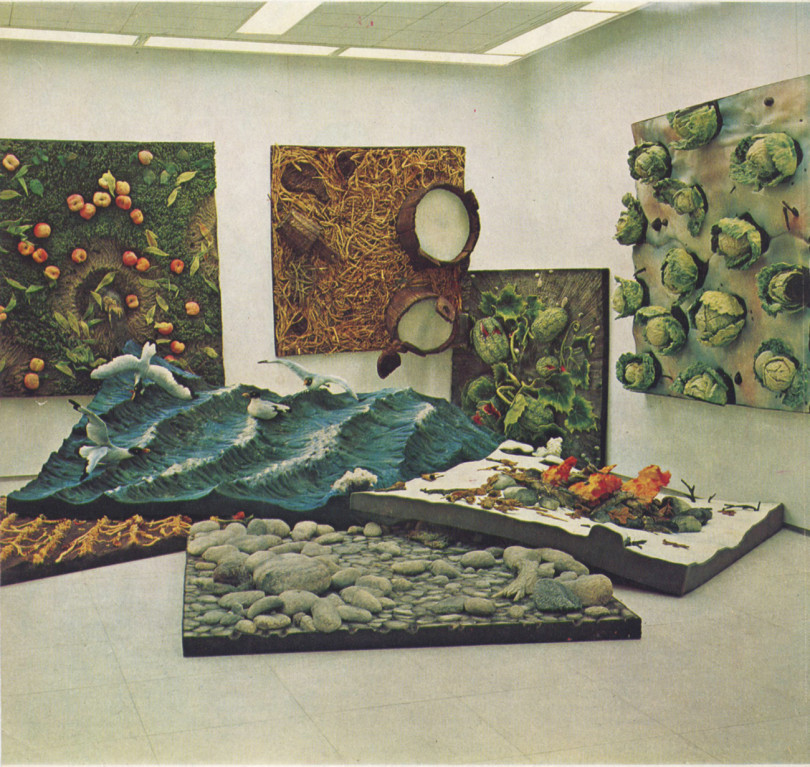

Although Gilardi was in many of the early arte povera shows, he was considered a technological “arcadian,” whose work was about our estrangement from nature and the possibility for new materials, such as polyurethane, to create a new “nature” for us. Lost nature was the subject of the work, hyperrealism was the technique. Gilardi’s simulations are not representations but substitutes, therefore quite distant from late sixties arte povera.

Before the Bertesca show at the beginning of 1967, Fabro had a show at Luciano Pistoi’s gallery: Notizie, more or less when Boetti had his first show at Christian Stein’s newly opened gallery. Fabro’s work was immediately recognized as being about the individual’s attempt to get to know his environment, beyond any specific aesthetic questions. Boetti’s work was then seen as stressing elementary action in a non-analytical way. In June of that year, Carla Lonzi curated an exhibition of Kounellis’ work at the Ariete Gallery in Milan. Pistoletto, together with Gilardi, Piacentino and other Turin artists had already formed a sort of group for the exhibition Am abitabile at the Sperone Gallery in 1966. Piacentino showed minimal-looking structures referring to interior decoration (tables, columns, etc.): useable, new design. Still before the Bertesca show, in June, 1967, an important exhibition curated by Calvesi and Boatto called “Acqua, Terra, Fuoco, Immagine” was held at the Attico, where Gilardi presented a tappeto-natura, Pistoletto exhibited a mirror, Pascali showed his first earth and water works (9 m2 of puddles and / m2 of ground) while Kounellis exhibited his first Margherita with an ignited torch. At the Paris Biennial (1967), alongside Schifano and Festa, Kounellis and Pistoletto were invited, as were Ceroli, Mattiacci and others. At the Fischbach Gallery in New York, Gilardi exhibited his “rugs” in September. During his trip to the States, he became aware of new art burgeoning there too, in opposition to minimalism, a more “humanistic” art where “personal reality” was being objectified, and he recounted his experiences for an Italian public in a series of articles for Flash Art where he also spoke of artists working in similar directions in Europe, such as Richard Long and Barry Flanagan, and concluded he was interested in seeing what some of his Italian colleagues, such as Zorio and Pascali, were about.

After “Acqua, Terra, Fuoco, Immagine,” in Rome, a large exhibition was held (July-October) in Foligno, called “The Spare of the Image.” Beside optical work such as Alviani’s, urban context art such as Tano Festa’s or Pistoletto’s, or its negative equivalent such as Gilardi’s, younger artists such as Pascali (with his 32 m2 of sea), Fabro and Mattiacci were included. For the occasion, retrospectives of Lucio Fontana and Ettore Colla were held, pointing to some of the main sources for arte povera. Colla, since the ’50s, had been making sculptures out of found, old rusted tools or other iron material, somewhat more lyrically than, for instance, David Smith in America. Colla’s sculptures allude to early man’s use of tools, an archaic world at the beginning of civilization. The passage from a new Dada sensibility to an interest in “poor” installations was noticed by Giorgio De Marchis on the occasion of this exhibition: “Space is no longer represented but useable; the spectator is invited to participate rather than to take part in communication … There exists a context rather than an iconography for the image” (July 1967). Then in September came the Bertesca show curated by Celant. Boetti exhibited his Catasta. Fabro his Pavimento-tautologia, made of newspapers spread out on the floor, Kounellis showed an iron and coal structure, Paolini his Lo Spazio, which consisted of eight white plywood logotypes covering the walls of a room and thus defining it: a discrete and conceptual intervention to incorporate the environment and hence the viewers in it. Pascali showed Due metri cubi di terra, already shown in Rome, and Prini Perimetro d’aria (lights placed in the corners of the room and in the center). Together with these artists, later defined as poveristi, in the “Im Spazio” section there were also Bignardi, Ceroli, Icaro, Tacchi, Mattiacci, all artists coming from the area of semiologic appropriation of the contemporary context. Tommaso Trini in an article for “Domus” dated January 1969, “New Alphabet for Body and Matter,” suggests how ante povera was not antitechnological but anthropological, and the opposition between natural and artificial materials was a wrong one: “If Mario and Marisa Merz, if Prini and Zorio could use materials from Dow Chemicals or logical schemes or programs from IBM, they would probably use them in a way similar to their use of craft elements and familiar materials … These are instruments of liberation and affirmation of original needs.”

After the Bertesca show and the Attico group show, Daniela Palazzoli curated the exhibition “Con temp-l’azione” in Turin (December) in three different galleries (Stein, Sperone, 11 Punto). The exhibiting artists were Alviani, Anselmo, Boetti, Fabro, Merz, Mondino, Nespolo, Piacentino, Pistoletto, Scheggi, Simonetti and Zorio — a mix of generations from which both Gilardi and the Roman artists (Pascali and Kounellis) were excluded. In other shows, such as “Collage” in Genoa the following December, Roman artists such as Mambor and Tacchi were included, pointing to how fluid and uncrystallized the situation still seemed. The following March (’68), Celant curated the Arte povera show in Bologna (De Foscherari Gallery) which did not have the resonance of the Bertesca show, nor of the later show “Percorso” at Mara Coccia’s gallery in Rome (Arco d’Alibert — March-April, 1968), a sort of Roman premiere for the Turin artists (though Giulio Paolini had already had his first one-man show in 1964 at Liverani’s La Salita Gallery). In “Percorso,” Anselmo, Boetti, Merz, Mondino (who was never really an arte povera artist but worked closely with Christian Stein at the time), Nespolo, Paolini, Piacentino, Pistoletto and Zorio exhibited and the show was reviewed by Alberto Boatto in Sargentini’s magazine Cartabianca. Therefore, the early work done in Italy seemed to have come out of a fertile encounter between what some artists were doing in the North and what some others were up to Rome.

Celant, by referring to “guerrilla” art in his first article-manifesto, made an indirect analogy between what was happening in art and the general social uprising of the late sixties — sexual liberation, antipsychiatry, the movement against rationality and technocracy, the New Left. In fact, Gilardi at first thought his tappeti-natura were a form of revolutionary new anti-design to render late capitalist man’s environment more agreeable, redirecting technology and functionalism towards a general, capillary aestheticism, and he sold his “rugs” by the square meter (only later realizing he wasn’t changing much!) Beneath this questioning of the art market, there lay a deeper, more important rebellion in art, the deconstruction of the modern, autonomous, rational, analytical subject, the last major development of which was, in Italy, arte programmata. The critic Giulio Carlo Argan supported this movement in the early sixties, which then became dominant by mid-decade. Argan had spoken of a programmed art, in symbiosis with technology, and of the death of “art,” while Celant functionalism towards a general, capillary aestheticism and he sold his “rugs” by the square meter (only later realizing he wasn’t changing much!) Beneath this questioning of the art market, there lay a deeper, more important rebellion in art, the deconstruction of the modern, autonomous, rational, analytical subject, the last major development of which was, in Italy, arte programmata. The critic Giulio Carlo Argan supported this movement in the early sixties, which then became dominant by mid-decade. Argan had spoken of a programmed art, in symbiosis with technology and of the death of “art,” while Celant later spoke of its rebirth as the acceptance of incoherence and the search for a renewed unalienated individual relationship between man and his environment (with a touch of anticipation of the ideology which today is known as ecologism!) In line with workers’ demands for self-management he proclaimed a multidimensional man dispersed in aesthetics. Piero Manzoni, protoconceptual artist very much related to Fluxus as well, anticipated and radicalized a movement of art towards life and expansion of the art object’s identity, finally incorporating the entire world as a “sculpture” (Socle du monde, Denmark, 1962). Manzoni’s attitude was not, however, proto-postmodern in the manner of arse povera because each of his projects, especially the merda d’artista, can be seen as an extremely rational radicalization of the principle of authenticity and of autonomy of art as layed down by neoclassicism. There is never incoherence in his projects.

Celant has always spoken of Italian art as baroque and fluid, as opposed to a more rational attitude dominant in the U.S. But this does not take into account much work being done there in the second half of the sixties, such as Sonnier’s, Nauman’s, Smithson’s, and California Funk art, even though, in his well-known book Arte povera, published in 1969 by Mazzotta, the critic includes both Italians and such artists as Nauman, Dibbets, Kosuth, Barry, etc,

The point to be made is that the opposition of Europe and America as arte povera versus minimalism no longer seems to stand, even though, at the time, from a local, Italian point of view, it might have looked that way, because young critics in Italy were aware of what was going on in avantgarde galleries locally, while they probably were more aware of what had already made it into museums abroad, such as the “Primary Structures” exhibition at the Jewish Museum in 1966, than the new “open,” nature-oriented and subject-oriented art abroad. In Italy, the move was more a generational one than a “national” refusal of foreign “minimalism,” a move from Pop/New Dada art to Pascali and Kounellis and Pistoletto (which explains much of Boetti’s design-oriented work in the late sixties) combined with the heritage of Lucio Fontana’s spacialism and Ettore Colla’s use of tools in the myth of man’s unalienated, early modern labor, some of arte povera (which explains for instance, Pascali and Fabro’s work). Fontana’s idea of the presence of space, as well as the tearing of the canvas, has to do with the heightening of actions which bring the subject out of the autonomous work into the environment, as well as with an idea of the poverty and simplicity of a gesture which is at the same time grand. In Rome, Tana Festa’s use of shutters as a base for his work also seemed greatly relevant to many younger artists showing at the same gallery (La Tartaruga), such as Kounellis and Pascali.

A very early expression of anti-minimal aesthetics in the United States was the “Eccentric Abstraction” show at the Fischbach Gallery in September 1966 (Sonnier, Hesse, Nauman), but only in April 1968 did Robert Morris’ article on “Antiform” come out, and only in October was Smithson’s “A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Pro-jects” published in “Artforum,” at the same time when the group show “Earthworks” (Morris, De Maria, Long, LeWitt, Heizer, Smithson) was held at the Dwan Gallery. That same month, John Gibson showed “Antiform,” with works by Ryman, Hesse, Serra, Sonnier, Saret and Tuttle. Anselmo and Zorio were included in Leo Castelli’s “Nine” at Castelli show in December. Outside Italy in Europe, Beuys, too, began to work with organic matter in the late sixties, after his Fluxus period. In September 1967, when Celant’s seminal show was on at the Bertesca, Paul Maenz organized “19:45-21:55” in Frankfurt, with works by Dibbets, Flanagan, Long and Roehr.

From 1968 on, the situation precipitated from galleries into more public exhibitions and museums: “Prospect ’68” at the Kunsthalle in Dussedorf, in September, the installations and performances at the Arsenali in Amalfi in October, promoted by Marcella Rumma, where foreign artists such Dibbets were also invited. In March 1969, major public exhibitions were held abroad: “Op Losse Schroeven” at the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, where Beuys blunted the corners of a room with butter and Prini put a tent up outside the museum, and “When Attitudes Become Form” curated by Harald Szeemann at the Kunsthalle in Bern and then at the ICA in London. In May, a large group show was held in Essen. Carla Lonzi’s book, Autoritratto, came out that year as well and, finally, in January, 1970, in Bologna, a group show with arte povera artists was held and publicly “sanctioned” the movement in Italy. In May that same year, in Lucerne, J.C. Amman curated “Processes of Visualized Thought,” which was followed by the X Tokyo Biennial, “Between Mind and Matter” (with Fabro, Kounellis, Mario Merz, Penone and Zorio) and in June, in Turin, Celant’s “Land Art-Arte Povera-Conceptual Art,” which included artists such as Kosuth and Wiener and marked the way towards more dematerialized forms of art. The exhibition of Italian art, curated by Celant in Munich in May 1971, was called “Arte povera,” but actually included works by artists such as De Dominicis, Pisani and Salvo who began exhibiting slightly later than the mainline “poor” artists and whose attitude towards art and life seems somewhat different, no longer in tune with a feeling of Marcusian liberation or renewed subjectivity as experience of the flux of energy in the world. These artists partake, in fact, of a more Heideggerian attitude of movement out of time, a synchronicity which allows therefore for reference and memory, for quotation and irony. In some ways, Paolini’s work, like that of many other artists of the late ’60s, radicalized the linguistic possibilities of art, substantially dissolving the metaphysical modern subject into a relativistic, diffused subject of a capillary telematic society. There is an indirect continuity therefore, that runs down through anti-form and arte povera to intertextuality and the “weak” relativistic subject of the 1980s. From this point of view, the rediscovery of subjectivity, typical of our self-service society following the crisis of social-Marxist ideology in the seventies, is not so much in conflict with the thought of 1968, but its development. Althusser, Lyotard, Derrida and Baudrillard, as well as Marcuse. Fromm and Reich all produced significant work in the course of the sixties, wine of them directly undermining the rational autonomous subject of Enlightement, some of them, instead, proposing a new anti-humanistic subject which exists in so far as its experience exists (Pascali!), a new, empirical subject (Fabro!) The ideology of progress and science, at the base of both capitalism and early Marxism, comes basically out of the Enlightenment, which Heidegger deconstructs. The convergence of Freud and Marx in Marcuse has to do with recovering spontaneity in a world based on repression (Beuys). More than by specific new feasible projects for the future, 1968 was characterized by movement itself (rationalizing this through the Maoist concept of permanent revolution). What was being discussed alongside racism, pacifism and Marxism was technocratic education, sexual liberation, feminism, self-realization, the refusal of the repressive, authoritarian bourgeois family structure. What was being undone perhaps unconsciously was also the work-and-savings ethic at the base of early capitalism, in favor of a pleasure ethic necessary to late capitalism’s survival as a consumer society, typical of the seven-ties and the eighties. In art, two main lines of work came of this (or determined it). On the one hand, Celant’s ideas about freedom and the flux of energy, basic to arte povera, are clearly traceable in Zorio and Merz’s work, just as in single works by other artists such as Anselmo (Tensione), Boetti (Taking the Sun in Turin), Pistoletto (Ball of Newspapers) Paolini (Deciphering My Visual Field). Fabro, etc. Another direction, parallel to this one, had more to do with a way out of modernism, out of the subject, out of history, progress and positivistic science, as in much of Paolini’s work on the absence of the Opus, some of Kounellis’ art, Gino De Dominicis’ paradoxes and black holes, Pisani’s reflections through irony and apparent explicit esoterics, Salvo’s work in the early seventies, Carlo Maria Mariani’s work of the same period, some of Ontani’s, some more recent work by Bagnoli and Spalletti (although the latter never uses quotation, but presents “presences” such as perfect useless vases and columns, and which turn reality into an abstraction by the presence and reality of their own being).

PASCALI

Pino Pascali had an appropriative, child-like attitude toward incorporating incoherence and the world, life’s energy. Born in the South, in Bari, in 1935, he moved to Rome only in the mid-fifties, where he studied scenic design with Toti Scialoja at the Art Academy. In 1965, he had his first one-man show at Plinio De Martiis’ gallery, La Tartaruga, which at that moment was still the center of Rome’s art world. Pascali showed large shaped canvas reliefs, sometimes free-standing pieces, ironic monuments to womanhood or to the myth of ancient Rome: stylized anatomical parts, large lips and breasts painted over in glossy color. The shapes somehow recall Domenico Gnoli’s large women, as well as Cesare Tacchi’s work on unupholstered canvases. They had a Pop look, references to design and advertising and rhetorical images.

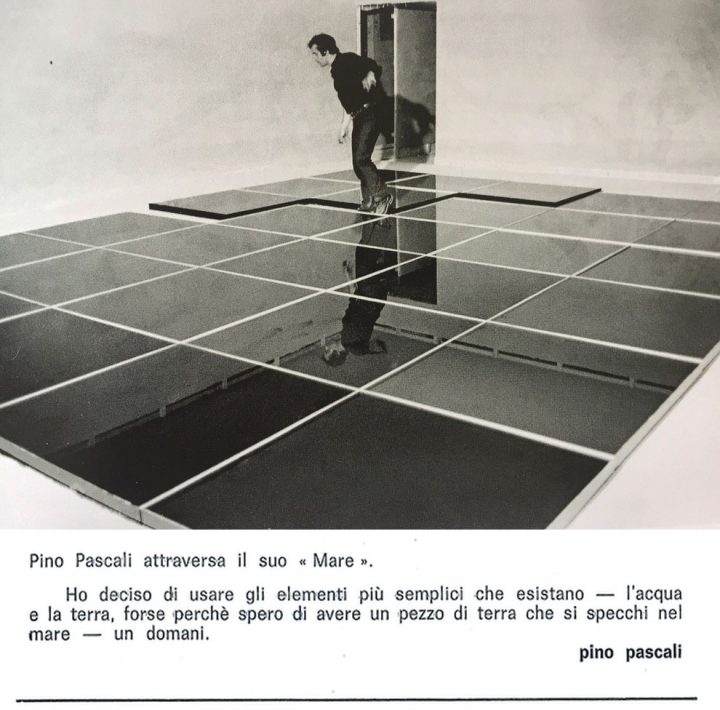

As this early date, Pascali was already experimenting with “soft” materials, as in his Muro del sonno (1964), a wall made up of cushions. The context he grew in was not late abstract expressionism, but the New Dada-Pop situation of the early ’60s. Pascali’s assemblages were not about combining differences, as seen the Cannoni (Weapons) which he exhibited at the Sperone Gallery in Turin, made of found objects such as plumbing tubes, leftover tools and things from body-shops, combined and painted over in monochrome military green so that they become absolutely verisimilar, illusionistic things you could take for real weapons. The works seem like real weapons, but can’t fire, ironically referring perhaps also to the U.S. involvement in Vietnam which was followed by demonstrations all over Europe. In 1967, Fabio Sargentini of the Attico opened a new space in a garage, on Via Beccaria, which he would use for many years as an unconventional exhibition area. This occurred shortly after he met Pascali and decided to exhibit his work. Pascali’s first show at the Attico actually took place in 1966, in the old space which the artist literally invaded with a shaped canvas Mare (Sea), 24 pieces filling a room of 4 x 6 m. There were also his animal shapes; the canvas was raw and light in effect, much the opposite of the Weapon series in that the forms were any-thing but verisimilar. These are “fake” sculpture, an ironic take on Arp-like shapes.

Immediately after his first Mare, Pascali got the idea of working with real water, enclosed in flat, aluminum containers, as in 9m2 of Puddles (1967), show in “Acqua, Terra, Fuoco, lmmagine” in June 1967. Near it Pascali placed his Square Meters of Earth on the wall, and the two pieces seem like an anti-form, arte povera reaction both to Carl Andre’s floors and Donald Judd’s wall pieces, which had been brought to public acclaim by the exhibition “Primary Structures” held at the Jewish Museum in New York in April 1966. In the Attico show, Kounellis exhibited his first fire piece, Margherita (Daisy) made of cut copper sheet and a blue gas flame in the place of the pistil. Pascali created forms which look like primary structures but are actually as unstructured and fluid, as organic as water or dirt. The work with water then become a series, as Pascali then showed his 32 m2 of Water at the “Lo Spazio dell’immagine” show in Foligno a month later (July ‘67), also shown in the Bern Kunsthalle. He sometimes combined water and earth, often in shapes that recall irriga-tion canals and plowed land ready to be sown (Paris Biennial, etc.) In March 1968, Pascali had another one-man show at the Attico, where he exhibited his Bachi da setola (a play on silkworm, baco da seta, and setola, bristle brushes), long worm-like chains of nylon brushes in different colors, as well as his Ponte, a primitive-looking foot-bridge made up of steel wool pads, like those used to clean pots. He also participated in person, dressed like a wild caricature of a primitive Indian or aborigine, dressed in straw. At the Venice Biennial, he showed his last works, made of all kinds of materials, such as feathers and fake, acrylic fur, but also sticks and straw, primitive agricultural tools, tribal adobe, late capitalist society products, all together in such a way as to release the primitive, “heart of darkness” energy latent even in contemporary man’s mind. His last piece, in 1968, shortly before his fatal motorcycle accident, was a short film Luca Patella made of the artist, perhaps the only Italian example of land art on film, which was being done abroad. First, Pascali’s hand emerges from sand, then his head, then his whole body: energy blasting up from the earth, rebirth. Pascali then proceeds to cut the sea water with scissors, plow the sand with a primitive tool, and plant bread loaves upright in the sand (not grain!) with the humor characteristic of all his work. Pascali’s acts seem to indicate the search for a subject once again in tune with the energy of nature, as in early man’s first society, the myth of unalienated labor.

In other words, Pascali can be considered as a sort of link between the early sixties Roman avantgarde and what was later defined as arte povera. The exhibition at the Bertesca in Genoa represented a sort of meeting point between the “Turinese” artists (Boetti and Paolini) and the “Romans” (Mambor, Tacchi, Kounellis). Pascali and Pistoletto were not included in the exhibition, yet the former was already considered a “star” by artists, and he had already considerably the influenced evolution of contemporary art in Italy. The Cannoni, the Solitario (1966), the acrylic plush works, as well as the works in steel wool maintain one of the peculiarities of Pop experiences, the ironic recovery of late cheap consumer products. Acrylic plush is symptomatic of a consumer society where real fur is replaced by an industrially produced imitation. This works in the same area as Schifano’s detail enlargements (the Coca Cola trademark) or Cesare Tacchi’s lined upholstery paintings and furniture/non-furniture. Pascali’s main innovation was to connect this procedure with an invasion of the environment, just as in Kounellis works, as with the dancer performing in front of the paintings or the real birds inserted in the work. Later on, Pascali further widened his range of materials to the point when he almost systematically combined organic matter like earth and water, sometimes with typically industrial shapes as in 32m2 di mare circa.

Therefore, Pascali used all sorts of “poor” material, natural and industrial, even if he never used differently characterized materials in the same work. He did not work on that kind of tension as Kounellis does. On the contrary, Pascali’s works constitute a whole which seems eclectic, an attempt to go beyond style which gives Pascali a pre-conceptual dimension.

ZORIO

Zorio is a (true blue) arte povera artist, perhaps (together with Mario Merz), the only consistently “poor” of the whole group (which it never really was, anyway). Right from the start (his first one-man show was on in the fall of 1967 at the Sperone Gallery), he began concentrating only on energy and “attitudes” becoming forms, either bringing natural, chemical processes into the work itself (coloring is a chemical process, he suggests with Rosa-Blue-Rosa, 1967, a tube like the ones used to make exhaust pipes cut in half and filled with a substance that veers to blue according to the humidity in the atmosphere), or fixing them right before or after their occurrence (Odio, written with a hatchet blows in the wall), but never bringing memories of art or its conventions into the work, not even references to stage sets as in Kounellis’ installations. The critic Tommaso Trini curated his first show, stating that his work was “more physical than most of the work being done … There are no questions of space, form or structure. The forms are the passive results of actions and physical laws.” Mass is continuous energy, even in his early works made of metal scaffolding, cloth and salt water evaporating and leaving crystals behind. Much of Zorio’s world recalls the mythic semi-barbarian middle ages alchemy, cruets, leather, red stars, thin slender canoes, fences and grids, blacksmiths, javelins, etc. Yet there are no metaphors in his work, and there are never stories, just as his To Purify Words (which has been developing since the summer of 1969) have to do with an attempt at reaching the rhythm and latent “attitude” of language, beyond communication. In an interview with Joie De Sanna (published in Data, April 1972), Zorio describes being “interested in work which stimulates for all the time that it physically exists I have always tried to remove technological functions from all materials. My work with lights that face each other on the floor came out of the idea of giving back to light its original function, which was not that of lighting up a room or a table but being heat, a source of energy … I conceived this work as a sort of little competition with the sun.”

MERZ

While Zorio began exhibiting with arte povera, Mario Merz, instead, started out much earlier as an abstract expressionist painter. Then, in 1967, as if by a sudden revelation, he began to use neon tubes and objects such as bottles, which he exhibited at Christian Stein during the exhibition “Contemplazione” in Turin in December 1967. His works had to do with objects and energy: neon as an actual flow of energy, coming out of the bottle, power becoming water, and viceversa. He soon developed installations with bundles of sticks, cars, earth, stone slabs, metal, wax and newspapers, often referring to an igloo shape, a versatile abode to render in a myriad of different ways, from the Igloo di Giap to Object Cache-toi. His works have since the beginning been about growth, not just energy, that is, not about a constant flow of experience but about exponential situations. His mind, taking possession of the world and its procedures, does so through Fibonacci’s sequence of numbers. His work is therefore not about lines but circles, not about leaves of grass but about arborial ramifications, not about cubic houses but igloos, not about the “masses” but about the progressive filling of a canteen by workers on their lunch break (La Mensa). His work is three-dimensional but also flat and often monumental. In a recent exhibition in Naples (“Onda d’urto,” Capodimonte, April, 1987), all these basic elements were present and interacted to form a nave-like, post-iconographic space of sacredness. His work fills space up, yet leaves it transparent and clear, as in his corridor Onda d’urto which could be a nave, a road vaulted by trees, a greenhouse or a strong wave about to break. The newspapers that run through it in uneven piles are accompanied by neon Fibonacci numbers, like the neon running through and out of his first bottle back in Turin in 1967. Merz’s work refers to a strong, powerful presence, a subject capable of “knowing” and appropriating the world’s energy, in a unitary view.

FABRO

Luciano Fabro’s work is not based on growth but upon a tentative appropriation of space which is not rationalistic, abstract nor “modern” or modernistic. In fact, Fabro’s geometry is empirical and approximative, never rigid, a sort of perspective before “scientific” perspective, as in the Pieroni Gallery environment (1982) where gold wooden listels divided the walls into squares. Fabro’s use of iron, brass and other metals evokes the direct manipulation of metals in the earliest stages of civilization. Already in In Cubo (1966), and right up to the recent environments such as Habitat di Aachen, space is not mental or pictorial but it is actual human space, the habitat or home, and Fabro’s work indirectly suggests a subject who again takes possession of his environment by joining it, a subject who reinitiates the process of acknowledging, putting an end to the par-able of the modern, detached, metaphysical subject. Fabro’s spaces could be related to Nauman’s environments even though he never uses means such as neon which could be related to the late-capitalist service economy, not even polemically, as Nauman does when he turns neon back to a fluid and organic form.

Fabro’s intervention tends to be light, subtle, as in the metallic rods he uses in an attempt to lighten space and render it clear. In Sonsbeeck’s La doppia faccia del cielo (1986), a huge heavy stone similar to the enlargement of a primitive tool of the Stone Age, is suspended, supported by a net, like a fish caught at sea. Similarly, his heavy marble or glass feet are rendered light both by the material’s transparency and the softness of the silk columns which link them to the ceiling, as if they were huge prehistoric animals’ legs gently taken down to the ground from the sky.

Even his early Tubo da mettere tra i fiori (1963) was a subtle and gentle appropriation of nature. Fabro’s reconstruction of the world starts therefore from below, from the individual, fighting a feeling of enclosure. In an annotation to a text by Joie De Sanna, Fabro added: “I go back to Manzoni from the Socle du monde to the Infinite Line … the gap between visual perception, the perceptive and intuitive, imaginative mechanics which was in those works.” In the recent exhibition in the Stein Gallery (1987), Fabro presented a huge mason’s rule opened in a zigzag shape, another definition of space, another appropriation. Yet here it seems to have been actuated by some enormous Gulliver, and the enlargement of the rule with clear centimeter and millimeter marks gives his work an ironic, almost hyperrealistic meaning, or makes it a simulacrum of his early works such as La Squadra (1966).

The Reversed Italy series, in various materials and shapes, is related to a collective image of man’s environment, to the more trivial but varied image of the nation and country. Fabro doesn’t lyrically invent a new shape, he (a bit ironically?) takes the readymade shape of his own country. Yet this is not a Duchampian, Neo-Dada or Pop readymade, since the inert object is avoided, if only by means of turning it upside-down. The variety of the materials repeats the shape but allusively stresses possible connotations within various contingent contexts: rich and golden Italy, Italy at war, Italy voting … Turning Italy upside-down saves the object from its potential tautological inertia, as if the mental time necessary to read the shape as a reversed Italy allows the presence of something between the sign and its referent, a moment à l’ecart where it might be possible to perceive what the shape normally has lost, or never had.

PISTOLETTO

Pistoletto’s Poetica dura works of the eighties are cumbersome, obtuse, vaguely geometrical volumes made from polystyrene. They are roughly painted over in black or in dark colors, they are not reflective and recall the overwhelming nature of his large balls of newspapers of the late sixties, among his most clearly povera works. They are like negatives of those, in that they do not even contain the connotations of contemporary media overdose that the crumpled newspapers did. These works do not incorporate the world, they are like fragments of simulated walls, where the artificial processed nature of the material is evident. They could be read as Pistoletto’s answer to the overdose of expressionism in the early eighties. They are unexpressive even if painted over loosely, showing the possible vacuity of individual gesture.

Pistoletto began painting in the mid-fifties, but had his first show only in 1960 in Turin. The works were vaguely figurative informale and matter compositions which recall Dubuffet but also Sironi. In 1962, he began using stainless steel as mirror surfaces onto which figures painted on transparent cloth were glued. He exhibited them in 1963 in Turin and then in 1964 at the Sonnabend Gallery. He later showed his mirrors with photographic transparencies of figures rather than painted ones, giving the work more illusionistic overtones. In October 1964, he showed similar works at Sperone, but mounted the life-size photos on plexiglass.

In 1966, in his own studio, the artist showed his “oggetti in meno” — a lamp, with a black band around its rim; an enlarged photograph of Jasper Johns; a green decorative pyramid center piece on a cheap folding wooden table with chairs; an empty glass, wood and iron vitrine; cement columns; a small model for a house (1.2 x 1.2 meters); a mirror; a bed; an ironic and kitsch imitation of an informal living-room-sized canvas; a burnt cardboard rose, etc. They were elements of interior design, both functional and decorative, but all certainly squalid, haunting, obtuse.

One of the oggetti in meno was an old wooden sculpture of the Middle Ages on an orange box of plexiglass as if it were its museum base. Here the base is more a sign of the loss of iconography, and of today’s impossibility of representation. Oggetti in meno are “absent” objects, furniture and interior design for one who is absent; they are subtracted from reality. Some of them recall abstract expressionism, others the readymade, others Pop Art, others design, others building constructions, as if style, too, was absent. They are the products of a hollow, lost modern man. Stylistic incoherence masks the absence of the subject, “l’artista in meno.” Here, art is “in meno” too. The Ufficio per l’uomo nero (1970) was an installation that included once again oggetti in meno (photographic enlargements), but with a television on. The “black man” is the hollow man, a ghost leaving traces of his environment.

His objects, or minus-objects, were exhibited in 1966 at Sperone, together with Gilardi and Piacentino, in an exhibition entitled “Arte abitable.” Well before arte povera was coined, Pistoletto was showing abroad (“A Reflected World,” Minneapolis, 1966) and in December, 1966 he had a one-man show at the Bertesca in Genoa, before Celant’s group show “Arte povera;” Trini curated his show in Milan in February, 1967; he held a solo show in Brussels at the Palais des Beaux Arts in April that year, at the Kornblee Gallery in New York and at Sonnabend in Paris.

While in younger artists’ works today there is a quality of desire in relation to design, a yearning for presence, Pistoletto’s oggetti in meno were only denouncing emptiness. Dialectically related to these are his mirrors doubling man and therefore allowing moments of self-recognition, albeit of a fictive subject. “When man realizes he has two lives, one abstract where his mind is, and one concrete, where his mind also lies, he either ends up like a madman hiding one of two lives, acting out the other, or, like the artist who is not afraid, risks both,” Pistoletto wrote. The artist allows doubling in the mirrors, but exposes mourning when he makes his oggetti in meno, that is, the unidentified subject. The mirror is the possibility of the Other and the double, which is why he always places a photographic image of another person on the mirror as well. When there is no mirror, there can be no subject. What happens in the mirror is not really the incorporation of the flux or energy of life (except as light refractions); it seems more related to a feeling of loss of identity and of invasion by simulacra, reminiscent of Warhol’s attitude toward authenticity.

BOETTI

According to a common notion of arte povera as anti-form, freedom of spacing through different materials both cultural and natural in order to incorporate the latent energy of life, then Zorio and Merz are true arte povera artists, while Pistoletto and Boetti also consider contemporary loss of identity.

Alighiero Boetti’s early work, which was first exhibited in January, 1967 at Christian Stein’s Gallery, had to do with objects, furniture and design, with colors as they relate to objects in our mind, as in the case of Rosso Gilera Rosso Guzzi (1966), where two red slabs refer not to monochrome late-modern, autonomous canvases, to red that is red, but to the associations one immediately makes with the real the actual experience of red Gilera and Guzzi motocycles, as the names of these brands are in relief and the surface is enamelled like a car or bike would be. Although later works like 1984 are related to our perception of media images (covers of magazines are copied in pencil and layed out to form a pattern), his early work had more to do with the connotations of design. Boetti created new objects that have no function, but rather the memory of one, as well as the memory of actual experience, as Boetti always chose well-known items such as the cloth used to upholster beach chairs (Zig-Zag, 1966), or wood used to make benches, paper plates (Catasta, 1966), lamps (Lampada annuale, 1966), etc. Boetti added layers of connotations without adding elements, simply altering them. He transformed them simply into decorative modules, stressing certain qualities (the stripes of Zig-Zag are underlined by the numerous folds of the cloth, which in turn, recall the folding of the same beach chairs).

Another series of works has to do with transposing a verbal code into a visual one, as in the Virgole sequence of the ’70s, as if looking for a utopian situation where the writing of a word could correspond to the contour of its corresponding image. In the seventies, Boetti began to work with tapestry, as in his two Mille Fiumi, originally in book form—a utopian list of the thousand longest rivers, naturally full of questionable evidence, especially towards the end of it, as if the structure of the work mimicked the myriad rivulets of an actual estuary. The handmade quality of the work allows innumerable unpredictable variations, yet the whole is a coherent, crystallized experience. These works, although not executed by Boetti, relate to his own recent rubbings of objects – knowledge through prelogical handling. The tapestries, like Boetti’s Faccine, have to do with multiplicity in unity, the convergence of order and disorder. Boetti’s maps are tapestries where each country is given the colors of its corresponding flag, on the one hand turning the world into a great decorative pattern, on the other heightening its symbolic experience by laying political connotations over its boundaries.

Boetti uses signs which are usually very coded in such a way as to turn them into modular, abstract patterns, yet at the same time, the juxtaposition of very well known signs strengthens their connotative value. He desemanticizes while hypersemanticizing, allowing the paradox to baffle in its simplicity, as if its two poles were the dual nature of a man’s ego. Although Boetti’s objects come therefore out of a Pop situation, the artist refers to potential energy in all of his early works as well (rather than to effective energy as Zorio and Merz do), the potential light of a lamp which turns on only once a year, energy reflected upon by the mind, “realized.” His work is also often about stopping time (Taking the Sun in Turin on January 19, 1969) just as it is about incorporating the flux of time (stones put into the shape of a body on the ground, as if the sun had turned it to dust, slowly; the series of magazine covers, month by month, set side by side, homologized through being copied in pencil, etc.) Thinking in opposites is inevitable, but wrong, as the opposites coexist in single signs: order and disorder as the artist like to say. Many of his works are light, not dramatic, games the spectators can play. Boetti follows projects but is also intuitive and allows for error. He refers back to the complexity of the world through accumulation rather than tension. His works are a sort of diary of the world, full of images that would otherwise be lost. Rubbings, as in archeology, a way of retrieving meaning.

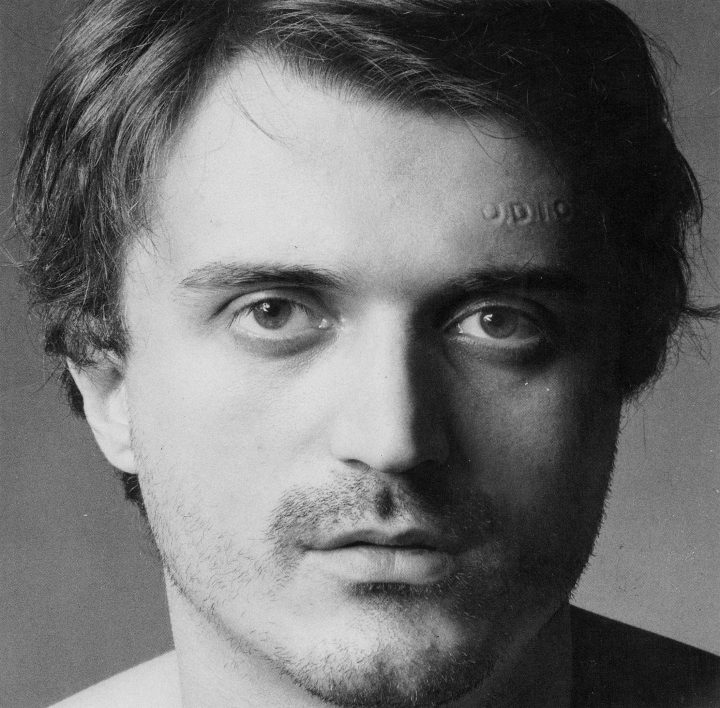

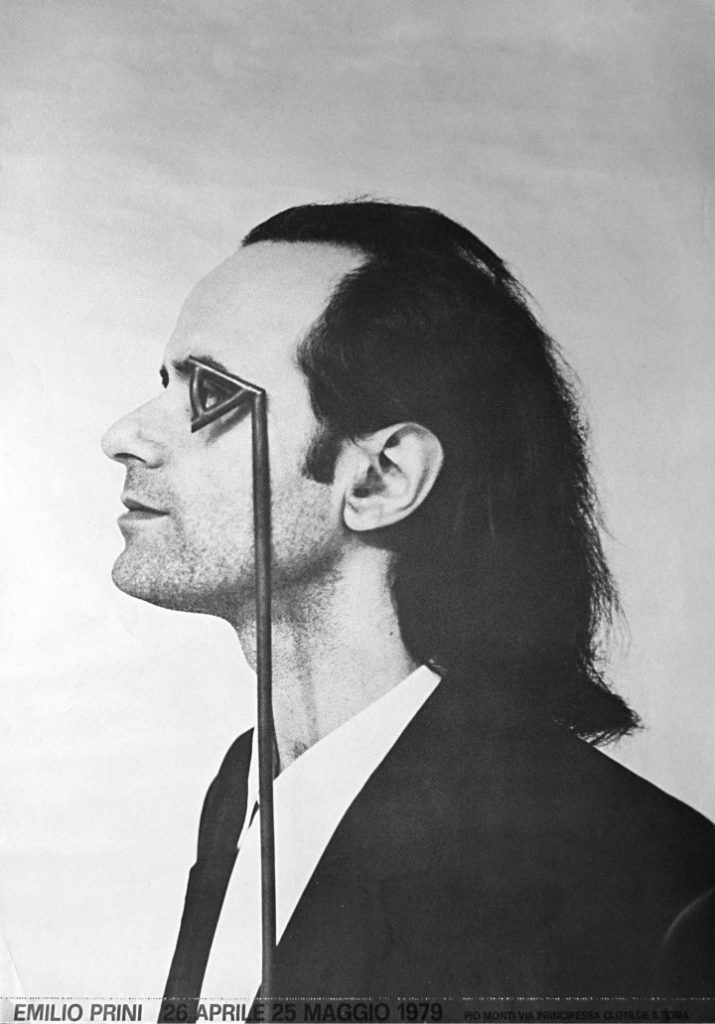

PRINI

Emilio Prini, born in Liguria (as was Germano Celant), constitutes, in this Italian map, a Genoese element which has been generally neglected, as compared to the Roman pole (Pascali, Kounellis and, later on, Pisani and De Dominicis), the Turinese pole (Zorio, Boetti, Paolini, Anselmo, Gilardi, Pistoletto) and Milan (Fabro). Prini’s work is the most dematerialized arte povera, even though it is certainly Paolini’s which is the most conceptual as far as an extreme search for art’s autonomy is concerned. Prini tends to identify the subjective, transitory and instantaneous experience of the Self with the realization of the work. The work, for example, exhibited in May 1968 in the “Teatro delle Mostre” at the Tartaruga Gallery consisted of a collection of the names of people whom Prini met on the train while travelling from Genoa to the exhibition in Rome. Aside from Prini’s “mental” subjectivity, the fundamental core of his work seems to be the search fora new contemporary icon, as luminescent and manifest as the Madonna or Annunciation could have been for the past. In a world which is no longer based upon the myth of origins, nor upon a Christian concept of future redemption, in such a world as the present one, dominated by standardization, Prini seems to say, the artist dis-covers new iconography, latent but already existing in the wild.

One of Prini’s first works (the Bertesca show) was a reel with lit neon tubes wrapped around it instead of the black cable usually found. Neon functions as a visible manifestation of flowing energy, it is a new, circular, even though standard light. Another work by the artist consists of a photograph of somebody lighting a cigarette where, as if by accident, the white between his fingers and the cigarette forms the shape of a star: no longer the Magi’s star, but one produced by the chance encounter of a machine and an ordinary instant of everyday life. Prini is perhaps the most radical Italian representative of the total symbiosis between art and life, where the material residue of an experience is reduced to a minimum—a few shots as documentation of the artist ‘tuning in” on a situation; a few rare and beautiful examples of photographic chance occurrences, errors ironically equivalent to early Christian miracles, but of our times, like a rainbow inexplicably formed by chemical reaction on a polaroid shot of an installation. His works are dry and detached, suspended between the banality of standardization and possibilities of vision.

ANSELMO

Ever since his often-cited trip to Stromboli in 1965 when he found himself the center of a landscape with the sun high above so that his shadow did not appear anywhere around him, Giovanni Anselmo has been working on the inversion of traditional representational art, maintaining, however, its conventions (but in reverse): his blue squares of paper on the wall, his grey stones, “che si alleggeriscono verso oltremare”, that lighten towards ultramarine, his compasses, his plexiglass, his white canvases piled up, but under the weight of stones, all refer to an “incarnated” art of nature. In 1969, in line with basic arte povera (poor implying not so much materials as authenticity of experience, convergence between life and art rather than fiction, as in “poor theater”), Anselmo stated that “I, the world, things, life, we are situations of energy and the point is specifically not to crystallize these situations, but to maintain them open and alive, functioning in our life.” That is, to maintain a mobile, relative, contingent subjectivity that exists in so far as it can manifest the energy latent in the world.

Anselmo’s materials are stones, compasses, light, ultramarine blue, time, direction, iron. In 1982, he exhibited Landscape, made of a hand-drawn on a large sheet of paper pointing out towards the viewer, a reversal of signs and referents where we are part of a “natural” landscape and the canvas is simply a canvas. Even though his heavy stones hanging from high up refer to weight and the imminent power of nature, they do so more lightly, paradoxically, than Zorio, perhaps because of Anselmo’s continuous use of them as materializations of the representational convention. The stones near the blue paper become signs of color on the background of a traditional landscape. Anselmo’s work is therefore actually not presentative, but metaphorical, in that it states a reversal between art and life. His arte povera was not simply a movement outside painting, this being true of Manzoni, Fluxus, Neo-Dada and many other manifestations of contemporary art. It was, more specifically, opposed to the idea that primary structures can exist at all, therefore opening up an infinite number of possible groupings of grey stones, each single and unique. Metaphor refers to imagined, distant space as well, not only the site of the installation, and compasses fixed in wooden or iron boxes point outwards towards infinity. The compasses encased in iron cannot be used by the viewer to read his direction in relation to the axis of the world. Instead, they point to the direction the entire world is going, in line with Manzoni’s Socle du monde.

KOUNELLIS

Jannis Kounellis’ work, as has often been said, is characterized by the convergence of hard, industrial structures and organic, unstructured, agricultural elements such as cotton, earth, flames, animals. Like Smithson’s stones in metal boxes, Kounellis puts charcoal into containers. But Kounellis adds an element of theatricality which places the work in an entirely different dimension. His installations, which follow a more New Dada-oriented period of work on signage in the early sixties (he first exhibited at Tartaruga in 1960), come out of a sensibility which redirects stage setting, rather than from enlivening “primary” structures, as Anselmo did. They therefore play on the idea of a fictive world full of memory and references, to be viewed as it were, from the outside. It is not by accident, in fact, that his early installation work often implied performances such as the artist feeding his caged birds set beside canvases, or unsnapping his stretchy cloth Rose from its base, or having a ballerina dance before a canvas. Music, the ultimate performance, often comes into the work, if only through the silent instruments leaning against a wall, with butane gas flames nearby. While Serra’s caged animals in his Roman show in 1966 (La Salita) referred somehow to man’s imprisonment, Kounellis’ eleven stallions (L’Attico, Spring 1969) were about harnessing and incorporating the beauty of energy, as in the case of his works with fire which date back to the seminal exhibition, “Acqua, Terra, Fuoco, Immagine.” In the late sixties, Kounellis saw fire as rebirth and rebellion and renewal, in the seventies as traces of past energy, reverting therefore to what was perhaps one of his inspirations to use this element in the first place, Burn’s Combustioni of the fifties. For Kounellis, though, the black marks of smoke are silent and solemn, set side by side on walls, like the fragments of a lost unified ego, far from the turbulence of Burri.

Kounellis’ juxtaposition of flames or smoke marks creates a classical order, like the columns of an ancient temple and, like those, serve to “hide” the volume of the temple itself, conferring an airy, celestial quality to it. Since the marks of flames run along the walls of an exhibition area, the temple they order and dissimulate cannot but be the world outside, somewhat like in the structure of Egyptian temples where the colonnade is within. Like Paolini, Kounellis has investigated the system of art, but whereas Paolini has observed perception only to find a hollow center the virtual absence of the work, the end of the concept of art’s autonomy since about 1973 Kounellis has staged the disintegration of art through its shattered fragments (on shelves, blindfolded, etc.) The present is fragmented with respect to the memory of unified past. Therefore, his best work has never been simply about grand gesture. It has actually been about the present as part of history, that is, about an attempt to explore and reflect the subject’s phenomenological relation with “things” and the world through changing historical contexts. His materials, both organic and inorganic, anti-form and industrial, have therefore remained relatively constant (iron, wax, fire, smoke, charcoal, wood, animals, wool, burlap, tar, gesso). But they dynamically relate and establish images, the overtones of which have radically changed over the past twenty years, marking a sort of convergence between a fluid, changing social world and an intimate, private code or language. The artist’s more recent work is far from the melancholy fragments of sculpture and traces of smoke which staged a flight into memory at the end of the seventies. Materials and things on shelves refer to all his preceding work as in a cold reflection: behind the classical order of presentation, there is no story and no history, but the sense of a new, impelling need: to recompose a world in order to momentarily recover a sense of rational self.

Certainly, this line of work has nothing to do with a sort of Marcusian, ecologistic dissolution of the modern subject typical of much early arte povera. To De Dominicis, the whole idea of incorporating energy and tension, as in Anselmo’s Torsione works, seemed absurd so he therefore placed a ball on the floor and called it A Ball the instant Before Rebound, pointing to a mental overcoming of physical laws, rather than to a reverence of them. Mariani’s early work, De Dominicis’, Salvo’s, Pisani’s seem in fact to belong to a more Heideggerian attitude of break from the modern subjectivity. This “other” line of thought has rarely been considered as a whole, probably because of the favorable reception the mainline arte povera work immediately received.

PENONE

From this point of view, Giuseppe Penone shouldn’t actually be considered an arte povera artist, but one involved in current questions of authenticity, of loss of touch with “things,” typical of recent work on negative design. Even though Penone might have written about the problem of how to capture the flux of nature and make a work of art out of that gesture, and even though his early carved wood trees responded to a need for tautological coherence of image and matter, they actually point to another direction. Often, the base of his tree sculptures is simply the cubic cut log of timber, as it would be bought to be used for construction. Above the base stands the perfectly simulated tree trunk, carved out of the same log, more “real” looking than reality. Therefore, the sign (the “image” pointing to tree) has taken on a concrete value, while the referent (the “real” wood) has become a sign, the base for a sculpture, pointing to art presentation. There is therefore no contradiction between Penone’s wooden trees and his more recent trompe-oeil bronze, sometimes humanoid, ones, and his recent outdoor installation in the park in Minister underlines this desire to discretely simulate nature within nature, rather than to represent nature. These principles were already evident from the outset of his work, as in his photographic selfportrait with mirrorreflecting contact lenses: eyes that can’t perceive an outside world, it seems, but that reflect it back onto itself, heightened into an inverted or hollow gaze. Penone’s pressure pieces, where he makes drawings of enlarged close-ups of skin, approach the point of becoming decorative, empty patterns rather than maintaining the connotations of real skin.

PAOLINI

If arte povera was about contingency, microemotions and fluxes of energy, then Giulio Paolini has made only one or two arte povera works, those where his attention has not so much been towards the analysis of the structure of art, but mostly about actual, individual perception or vision of it (Vedo-La decifrazione del mio campo visivo, Lo Spazio). If arte povera was about the enriching meeting of first and third worlds or, better, their recreation of a new man, “whole” as he was in early civilization, still unalienated from labor, empirical knowledge and emotions, then Paolini, as if by some mistake in history, has fallen into that sphere without belonging. His early reversed canvases with cans of paint, covered in plastic (1961), were Manzoniesque and proto-conceptual, and his attitude whereby the making of the work is the object of the work, the linguistic analysis of the art process, was conceptual.

Paolini’s art has always been about the perception of an image which can never really “be,” with a slightly nostalgic late modern attitude, an awareness that art’s autonomy has slowly reached the end of its line, closing a parable opened nearly two centuries ago with neoclassicism. To make this point, Paolini has used images (photos or plaster copies) from art history ever since his work of the ’60s (Ragazzo che guarda Lorenzo Lotto, Mimesis, La casa di Lucrezio) and these works have little to do with recent appropriation art (renunciation of originality, simulation) and serve, instead, to stage the loss of the Opus, the remnants of its impalpable space. Some recent European art is also dealing with the loss of the Opus, but while Paolini stages the loss of vision (of the image), today’s younger artists stage the vision of loss, therefore implying desire and an object-image, but not sculpture. Paolini’s work is about representation (and sculpture), while recent work is about deflecting communication and materializing signs from art, and by so doing, freezing and losing them. Therefore, Paolini walks a fine line between what could be seen as the dissolution of the rational modern ego in contingency (perception) and a feeling of break from the epoch of linear history (absence). In 1984, Paolini put the problem quite simply, “One might as well say it straightaway: the artist does not know objects, he does not see them. Yet, never so much as today have objects filled our daily scene, have they saturated our visual field. Who, then, is the artist, will he or will he not explain himself? Or, better, where are (where has he hidden) all those objects? The artist is someone who moves in the void without being able to give up describing it. His ‘object’ is the transparent film, the impalpable covering of this ‘void’ within which he finds himself. The object of his vision is his own vision which has, as its object, still another vision. Therefore objects do not exist because things exist, the thing. What thing? The thing itself!”

Many other artists were and are involved in installation-antiform-arte povera work. Marisa Merz’s work with cut laminates and then with other delicate, fluid metal forms were early. Pier Paolo Calzolari was in many of the later arte povera exhibits, often working with neon and sound. Claudio Cintoli’s work with tied ropes, Simonetti’s work with video, even Ceroli’s cut raw wood shapes have some relation with this line of art. Completely different in attitude and closer, instead, to some of Prini and Paolini’s work, De Dominicis (who strangely enough, was included in the important 1969 Munich show of arte povera), Salvo, Carlo Maria Mariani and Vettor Pisani break out from linear history through the use of irony and quotation. Just as different are Ettore Spalletti’s apparitions, absences which barely appear in pastel columns, vases and disks, proving their absurdity in a “real” context by revealing the absurd emptiness of the “real,” somewhat closer to the line of Penone’s simulations.