Barely two days into its existence, “Art of Change” found a critic in the authoritative figure of Ai Weiwei, who lamented the show’s lack of political engagement from the pages of the Guardian. It’s an observation that those who have actually bothered to visit the exhibition would probably debate; Yingmel Duan’s performance Sleeping, Patience and In Between (2004-12) or Xu Zhen’s stunning piece In Just a Blink of an Eye (2008), although not classic “river crabs,” are hardly apolitical. Yet Weiwei might have a point when he calls into question the necessity of having another West-centric, geographically themed exhibition about China in this moment. The timing, admittedly, might seem a little suspicious, but “Art of Change” doesn’t fall into the category of the bandwagon jumpers. The “change” to which the title refers, rather than pompously hailing the advent of a new age, is a reflection on a generation of artists who tended to focus on process as much as result, and the consequent “mobile” characteristics that end up inhabiting their work — a methodology that found fertile soil in China over the past two decades due to a number of factors, including the core presence of “change” in Taoist philosophies.

Performance art and installation (commonly referred to as xingwei-zhuanzhi in China) are two principal elements of investigation, both for their intrinsic qualities and for the peripheral, semi-clandestine circumstances in which they formed their identity. Several works in the exhibition are notable for their transitory nature — an aspect that resonates with the focus on mutable, day-to-day life as a source of inspiration. This phenomenon, once exported, has contributed to the fractious idea that underground automatically equals dissent, paving the way to a series of misrepresentations that this exhibition tries to rectify.

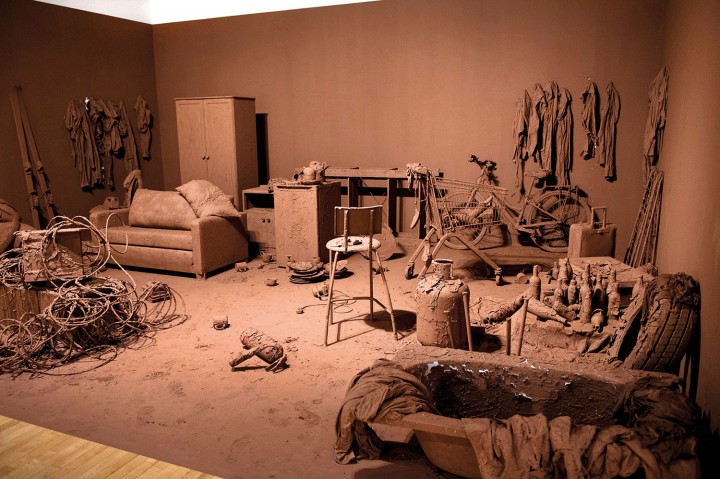

Curator Stephanie Rosenthal has identified Robert Rauschenberg’s exhibition at the National Gallery in Beijing in 1985 as a pivotal moment in the local definition of the concept of sculpture and performance, as well as the concomitant opening of Hou Hanru’s Shanghai Biennale and Ai Weiwei’s “Fuck Off” as times when mainstream and alternative clashed with no clear winner. Indeed, one of the difficulties in examining Chinese contemporary art from a historical perspective is how to reconcile the post-Tiananmen art that circulated in the 1990s with what followed once liberalization began. In this sense, the presence of Chen Zhen’s Purification Room (2000-12) is particularly interesting, as it provides a welcome opportunity to establish analogies and differences between one of the first artists who left the country (1986) and his peers. Another welcome inclusion in the show is Gu Dexin, who had his first international breakthrough at age 27 with “Magiciens de la Terre” in Paris (1989) before officially retiring three years ago.

It’s difficult to tell if “Art of Change” will have the power to win Chinese contemporary art a new audience. Although individually strong, some works still struggle to shake off the initial impression of being derivative. But for those willing to embrace it and find out more, it will definitely add volume to the experience.