In 1974, Anarchitecture, a group whose members included Gordon Matta-Clark and others connected to the artist-run gallery 112 Green Street, contributed a photo-essay to Flash Art, among the very few traces of their production. In the course of revisiting these images, Frances Richard revives the group’s debate about spatiality, sculpture and resistance.

In 1974, Anarchitecture, a group whose members included Gordon Matta-Clark and others connected to the artist-run gallery 112 Green Street, contributed a photo-essay to Flash Art, among the very few traces of their production. In the course of revisiting these images, Frances Richard revives the group’s debate about spatiality, sculpture and resistance.

“The term anarchitecture was more or less invented by Gordon,” wrote sculptor Richard Nonas in 1992, regarding his friend and collaborator Gordon Matta-Clark (1943–1978).[i] Nevertheless, as several decades of oral histories, critical articles and exhibitions have established, Anarchitecture was not a variety of building-based sculpture; despite Matta-Clark’s occasional use of the name to describe his geometric interventions into derelict built space, he was emphatic in the early 1970s that his pun was not a label for his art. Neither was it merely a wisecrack by an artist who had trained as an architect. Rather, Anarchitecture was a discussion group. Short-lived but influential, it was active in 1973 and ’74. Meetings were attended by Matta-Clark and Nonas, along with Laurie Anderson, Tina Girouard, Suzanne Harris, Jene Highstein, Bernard Kirschenbaum and Richard Landry, with input from others connected to the artist-run gallery at 112 Greene Street and FOOD Restaurant around the corner at Prince and Wooster Streets in SoHo. FOOD, 112 Greene Street and Anarchitecture interlocked in a downtown New York scene that Girouard describes as “anarchist.”[ii]

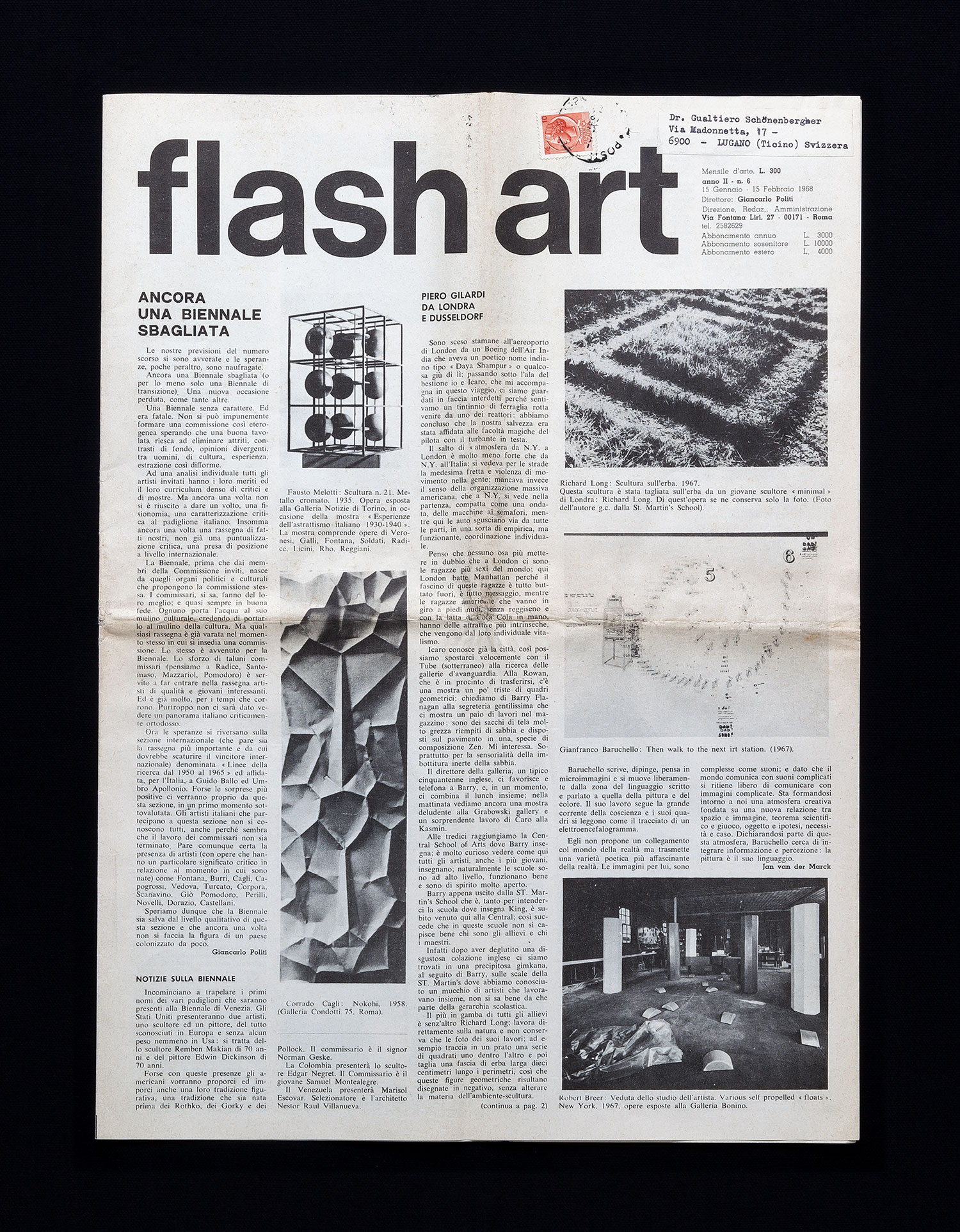

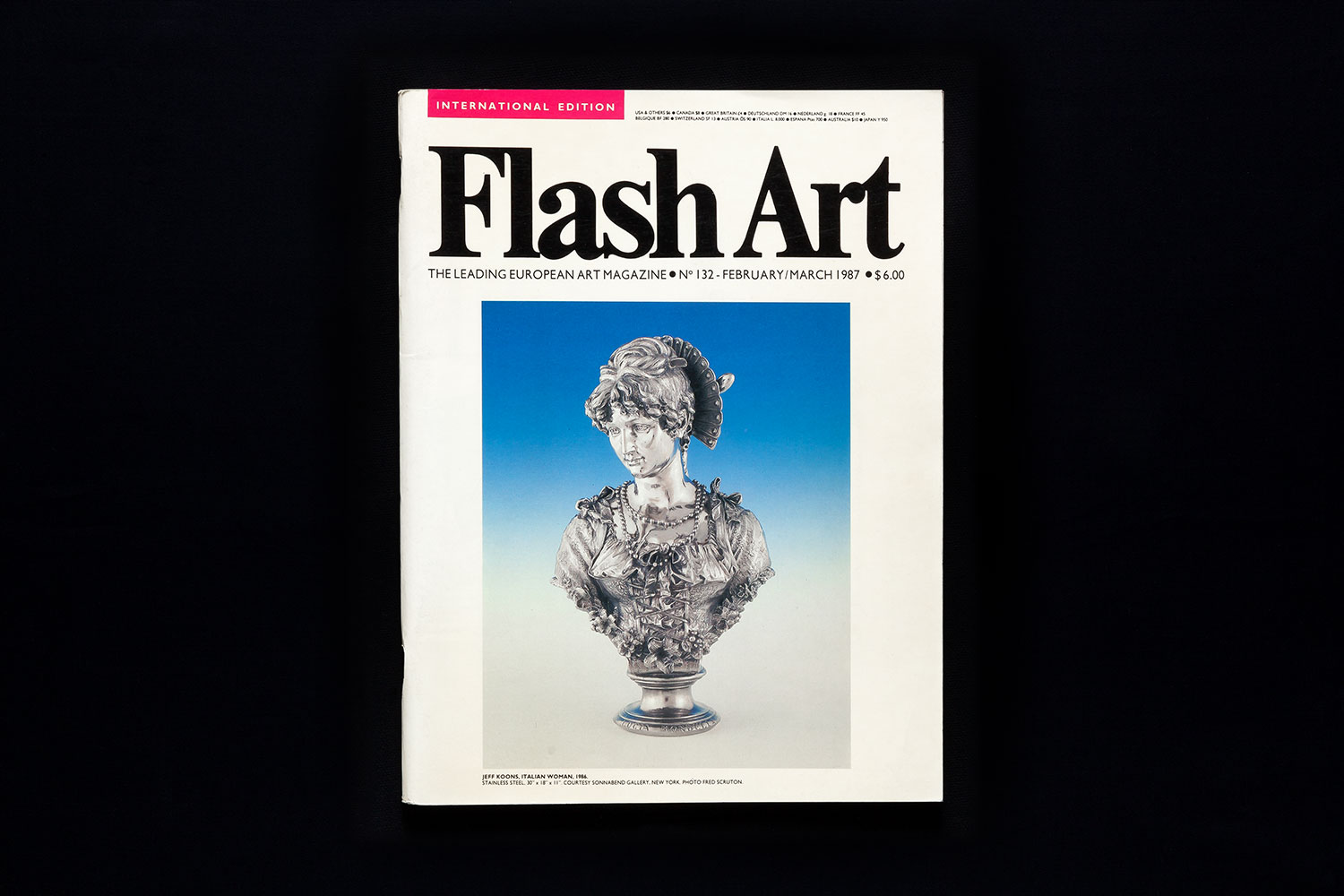

Anarchitecture produced one exhibition, at 112 Greene Street, in March of 1974. The twenty-nine photographs and drawings — some shot by participants, others culled from newspaper archives, all uniformly sized and hung anonymously — seem to have been largely Matta-Clark’s brainchild, pulled together to fill a hiatus in the gallery schedule. The contributors advertised their show in Avalanche magazine, another SoHo-based artist’s institution of the era, but none of them were wholly pleased with it; atypically for this group of camera-toting artists, no installation photographs seem to have been preserved. A few months later, in June 1974, an Anarchitecture photo-essay was published in Flash Art, reproducing a dozen images from the larger suite. The two-page spread, plus the exhibition and Avalanche ad, thus constitute the group’s public production. In Flash Art, a headnote explains:

Anarchi-tecture

The show was comprised of a collection of photographic notes evolving from a year of group discussion around mental, personal non structural or architectural notions of space and place.[iii]

Anarchitecture sought not to theorize “mental, personal, nonstructural notions” but to work inside them. Ubiquitous and protean, “space” was understood by these sculptors and dancers as a conduit through which they could continue research into the dematerialization of the art object and activation of marked sites begun by Fluxus, Conceptualist and Earth artists. Such inquiries introduced an active body back into artmaking, without returning that body to the psychological and spiritual grandeur it had borne in action painting. Because space is shared by all who inhabit it, the group could approach phenomenological and semiotic questions indirectly. They could treat a word or photograph — or magazine page — as a place, as real (or unreal) as a building or landscape.

“The Anarchitecture group — if I look at it from twenty feet away — was a completely literary thing,” remembers Anderson. “The talking was really a working method and a way of identifying with each other.”[iv] It is significant in this regard that eight of the twelve Flash Art images incorporate language. Reproduced in handwriting as opposed to print (exceptions are the headnote and list of participants), these verbal elements establish, inside the magazine, a visual correlate to the playfully embodied speech at Anarchitecture meetings.

Among the word-inflected images, three involve no photography at all. The collage titled “the crystal cue” is by either Highstein or Anderson; it describes Leon Battista Alberti — the epitome of Renaissance architectural genius — designing a basilica by chance operation.[v] The other two word-drawings were copied out by Girouard. The simpler of these, a trio of aphoristic sentences, juxtaposes Noah’s Ark and Christopher Columbus’s ship the Santa Maria. The other, occupying the visually and rhetorically powerful upper-left-hand corner of the layout, spins a series of puns on the core pun. Girouard’s explosively silly series, which suggest Conceptualist statements permuted through a Dadaist machine, are arguably the best extant expression of Anarchitectural thought:

AN ARK KIT PUNCTURE A KNEECAP FRACTURE ANACCUPUNCTURE

AN ARCHITECTURE IN ARCHITECTURE AN ASTRAL VECTOR

ANARCHY TORTURE ON ARCHITECTURE AN AUSTRAL UNDER

AN ARCTIC LECTURE AN ATTIC TORTURE A NECTOR TASTER

ATLANTIS LECTURE AN ARTICVECTOR A NARCO TRADER

AN ORCHID TEXTURE AN ART KIT TORTURE AN ASSTRAL FACTOR

ANT LEGISLATOR ANARCHY THUNDER A FILLIBUSTER

ANARCHY LECTURE A LETTUCE TEXTURE A FULLER BRUSHMAN

AN ART COLLECTOR AN ART DEFECTOR AN AUSTRAL BUSHMAN

AUNT ARTIC TORTURE AN ASS REFLECTOR AN ARCTIC TRACTOR

AN AIR KEY TALKIE AN AIR KEY TACTILE AN AIR KEY TICKLE

The five verbally marked photographs were captioned by Matta-Clark. His phrases do not elucidate their pictures as newspaper captions would; instead, the comic-poetic tags foster a relay between photography and writing. Inside the images, this slippage between two systems for making meaning is reiterated in the form of physical distances and/or inappropriate material meldings.

Such juxtapositions animate the diptych in the top row on the left-hand page, composited from two identical yet differently enlarged photographs. On the left is an appropriated shot of two carved columns. The nearer column repeats in the shot on the right, cropped tightly so that it looks larger; the effect is to mock up a row of three columns in faked perspectival recession. Scrawled across the sky are the words “PILLAR TO…,” as if proposing an Anarchitectural wandering from pillar to post through monumental-sculptural precedent and low-tech montage.

Another composite panorama presents a leafy shoreline seen from across a lake. Matta-Clark captioned this “THE HORIZON SHE IS JUST OUT OF REACH.” (Horizon lines in these three shots are carefully aligned, whereas in the “PILLAR TO…” photos, they are radically mismatched.) As a meditation on spaces that can be conceptualized, even viewed, but not inhabited, the unreachable “HORIZON” relates, in turn, to the close-up on the right-hand page of tire tracks embossing a perfect X in cracked hardpan. Matta-Clark titled this “AN ACCIDENTAL CROSSING ON THE MOON.” A joke about the Apollo-mission moon landings, this picture presents a facetious historical artifact; extending the relay of traces, fusions and impossibilities toyed with across the photo-essay as a whole, the “ACCIDENTAL CROSSING” rhymes with the claim “GEORGE WASHINGTON SLEPT HERE” written across a photograph of false teeth soaking in a wineglass filled with water. The tire tracks that index but do not picture human presence, and the prosthetic part that belongs not to George Washington but to the apocryphal anecdote about his wooden dentures, suggest that the absent or dismembered body can itself be understood as a culturally constructed space.

The last of the language-dependent images depicts corrugated elements stacked and neglected in a grassy vacant lot. This image is captioned “an OLD façade: packed & waiting.” The cast-iron buildings of SoHo, a.k.a. the South Houston Industrial District, belonged to the light-industrial Manhattan that had largely been dismantled in the 1960s to make way for a new, finance-oriented New York, heir to Corbusian promises of frictionless cleanliness; the lofts that housed Anarchitecture meetings had become available to their artist-inhabitants because the metal-stamping outfits and print shops that once occupied them had gone out of business. The façade parts in the Anarchitecture photo are waiting in postindustrial limbo for a reaffirmation of purpose that will not come.

Efficiency, use value and their failures likewise motivate the photographs in Flash Art that don’t depend on language. The hole in the ground, and the lighthouse nearly drowned in crashing waves, invert each other; down versus up, dark versus light, earth-and-air versus sky-and-water contrast, but each image represents an enticingly excessive materiality, a dynamism that can’t be instrumentalized. The same is true, in different ways, of the appropriated photo of a battered frame house being moved downriver on a barge. The building has been uprooted, set adrift. Yet there is a peacefulness to this uncanny motion, emphasized by the quiet ripples and pastoral reflection on the water. The merger of house with river implies a revelation: homeliness is founded on vagabondage. (And perhaps the refugees in Noah’s Ark, or the colonialist adventurers in the Santa Maria, would agree.) Yet this dream-equation can also be inverted to consider a transit so exaggerated that it flips into stasis — as in the photograph of a wrecked train car stranded on the pilings of a rural trestle that has fallen out from under it.

Anarchitecture was a premise about sculpture, a performative aesthetic and a print project. It was a means for Matta-Clark and his cohort to talk about their interests in zones of contradiction, trespass and vitality — and none of them seems to have taken this debate about spatiality, sculpture and resistance to rationalistic planning any less seriously because it was expressed in terms like “ANACCUPUNCTURE” (the healing piercing of buildings?) or “ANARCHY LECTURE” (the Flash Art spread itself?). Which is to say that, rather than constituting a group, or even a set of sculptural and photographic practices, anarchitecture was — and remains — an exercise in language, an elegantly simple poetic device for designating that which is there but not there, tangible but unreifiable. Anarchitecture identifies something, or someplace, that we know and often enter but can’t describe without such a suggestive name. It demarcates a space of experiment where architecture as order and measure is fused into the pleasures and dangers of anarchy, where “A FULLER BRUSHMAN” and “AN AUSTRAL BUSHMAN” are lords of misrule.