“Grande dame,” “sex,” “Dieter Roth,” “femininity,” “proximity,” “censored,” “folkloric”: these are but a handful of platitudinous words that often describe American artist Dorothy Iannone’s decades-long practice. Iannone, who was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1933, started painting in the late 1950s. She has developed a practice so idiosyncratic that most people have a difficult time describing it. And, though it’s hard to imagine sexual content being problematic today, the reception of Iannone’s most iconic works over the past sixty years — depicting figures in rapture donning swollen genitalia — has ranged from scandalized and censored to just plain ignored. It has only been in the last decade or so, perhaps since her inclusion in a 2005 exhibition at the Tate Modern via the Wrong Gallery, which led to her inclusion in the 2006 Whitney and Berlin Biennials, that Iannone has gained renown as an artist. Yet, retreading Iannone’s neglected successes throughout the years seems equally worthwhile and reductive: Why do so many critically important female artists only gain recognition well into their elder years, and why, when success does finally come, must the work be so characterized by a narrative of belated reception? At Berlinische Galerie Museum für Moderne Kunst, Iannone recently closed her first major institutional retrospective exhibition in Berlin, the city in which she has lived and worked since 1976.

Most narratives about Iannone’s work are organized biographically, which may seem facile at first — who cares about Richard Artschwager’s vacations or Albert Oehlen’s sexual partners? Still, Iannone’s paintings, artist books and sculptural video works often take her admittedly very interesting biography as content. Iannone’s oeuvre begins with her paintings and collages from 1959 through the mid-1960s, when her paintings took on a distinct Abstract Expressionist feel then popular among the East Tenth Street scene in New York. Although it’s self-evident that an artist’s early work can greatly vary from that created in one’s mature years — take the dissimilarity between John McCracken’s early mandala paintings and his sleek, minimal columns for which he is best known — Iannone’s early work may surprise those familiar with her most iconic paintings. The artist’s 1959 oil crayon on paper compositions Certainty, Impeccable, Impose, and Majestic melt Crayola-colored abstract forms into themselves, and appear as exercises for finished works. Iannone’s Remembered Child (1961) depicts a blackened abstract landscape with an oversized incarnadine moon, recalling (and predating) the muddy mixed media of Anselm Kiefer. Also from 1961 is the series “Kyoto Collage,” which delicately arranges hand-dyed Japanese paper into blocky figurations reminiscent of bonsai arrangements. Sunny Days and Candy (1962) continues Iannone’s interest in gestural abstraction, though the artist begins confining and outlining blocks of color, which begins to lay the groundwork for her more detailed and complex work compositionally inspired by Byzantine mosaics and Persian miniatures.

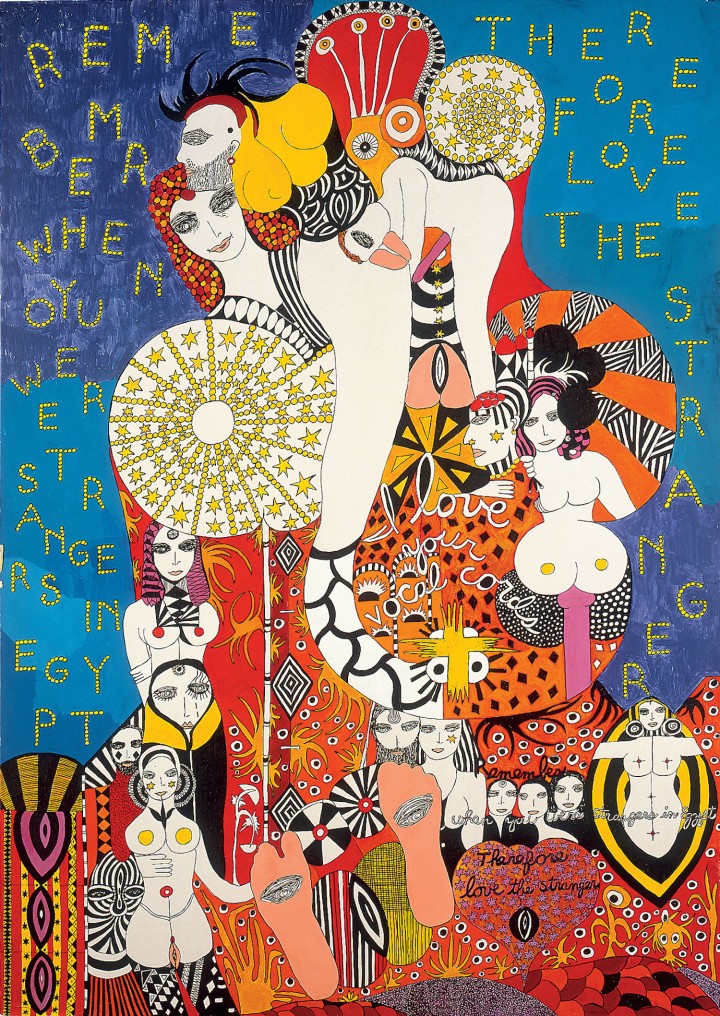

Big Baby (1962–63) and Sunday Morning (1965), both blocky oil-on-canvas paintings with predominately primary-color palettes, continue on this increasingly Byzantine path. Sunday Morning sees the introduction of repeating floral and architectural motifs bordering the canvas, as well as the inclusion of figures and text. The extraordinarily intricate All, a large painting completed in 1967, depicts nude female figures surrounded by tribal motifs, alhambras and what appear to be stylized stained-glass windows. It is rendered without a trace of her gestural, expressionist past.

In 1967 Iannone departed from New York with her husband, the investor and painter James Upham, and set sail for Iceland to meet a friend of Upham’s involved with the Fluxus movement. There, Iannone met Dieter Roth. He had been waiting for the couple on a dock, holding a fish, and a week after the two artists met, Iannone left Upham for Roth, staying with him in Reykjavik and Düsseldorf for seven years until 1974. During those seven years her work would take Roth as its content. It cannot be understated the deep, indelible impact Iannone and Roth had upon each other and their respective artistic practices, though conversely, Iannone’s union with Roth seems to overshadow the rest of her work. “Dieter Roth appeared in my work only for the seven years we were together,” said Iannone to me in an interview from summer 2014. “After that, with the exception of one or two special cases, never again. My work spans half a century.”

Nevertheless, Iannone seemed entirely aware of how special these circumstances would be in retrospect. She documented her life with and love for Roth through many paintings, collages, sculptures and even an artist book that narrated their time together, An Icelandic Saga (1978). Even in a 2009 interview with Frieze, twenty years after Roth’s death, Iannone speaks of the Swiss artist with fondness and familiarity: “Now, even though there are some things I would like to remain unchanged, I know that nothing stays the same. Over the decades, I have watched the images on the painting Dieter made for me gradually lose their substance as the fallen grains of cocoa powder accumulate under the glass on the ledge of the frame. Their loss is slowly revealing the color of the paint underneath, and somehow the picture has become not only more moving, but more beautiful to me.”

Also in 1967 Iannone completed “Dialogues I,” a narrative series of drawings on board illustrating a nude man and woman in various stages before and after coitus, oftentimes with text superimposed as a compositional element. In “Dialogues I” we see a female and a male figure negotiating bed space, having sex and turning off the bedside lamp amid a florid landscape trimmed with diamonds, daisies and paisleys. These drawings represent her mature signature style that combines text, decorative motifs and plainly rendered figures sporting engorged genitalia. Iannone would proceed to create many such series. The year 1967 saw a marked turn as the artist began to fully embrace the erotic nature of her work. Predating Tracey Emin by a few decades, that year Iannone made an artist’s book listing all of the men she had slept with — an act of radical transparency even today, and one of unimaginable bravery in the 1960s.

It should be noted that, although genitalia is almost omnipresent in Iannone’s work, her practice isn’t necessarily about sex — at least not the nuts and bolts of it, so to speak. Never do we see bursts of fluid or the dejected awkwardness of a failed erection or belated orgasm. Rather, with a healthy dose of dark wit, we see compositions about ecstatic unity, and the quotidian transcendence that can come from such unions. It is this daily celebration of life and love that is so crucial to Iannone’s work.

Importantly, the period in which Iannone and Roth cohabitated, 1967 to 1974, is also the crest of second-wave feminism and the heyday of conceptual art. Iannone kept her distance from both. Rather, her work is a product of a journey through and a celebration of life rather than a force intentionally oppositional to exclusionist conceptual art or the feminist scenes of those decades. “It’s not art talking to art,” she related to me. Yet it would be wrong to classify her work as non-feminist or anti-conceptual. What’s more, it reads as responsive to its zeitgeist, yet equally out of time and place in its borrowing of historical and pan-cultural motifs. In her work we can see the influences of worldwide travel: entwined figures of Indian tantric paintings, the complex patterning of Byzantine mosaics as previously mentioned, the craftiness of American folk art, and the erotic, engorged genitals of Japanese wood block prints. Such influences are evident in At Home (1969), a color silkscreen on paper that integrates various domestic scenes — cooking, eating, talking on the phone — into one labyrinthine composition.

Iannone spent considerable time in the Fluxus scene in Düsseldorf with Roth, and in 1976, after the couple’s break-up and a respite in southern France, she moved to Berlin on a DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) residency. In the late 1970s, Iannone began creating totemic sculptures inlaid with either sound speakers or video monitors. Most celebrated is her video sculpture consisting of a painted wardrobe-sized box with a monitor, installed head-height, which plays a video of Iannone’s face while masturbating. Titled I Was Thinking of You III (1975–2006), the sculpture was shown in the 2006 Whitney Biennial, and may have contributed to the resuscitation of her career. Similarly, the monochromatic three-panel piece Follow Me (1977) encases a monitor playing a video of the artist’s face, the painted panels surrounding it depicting a woman with a radiating halo and a man wearing a crown of thorns, both crucified. It appears to be a break-up piece. It reads, “FOLLOW ME; IT’S NOT TOO LATE TO REMEMBER WHO I AM; YOU WILL NOT BE VANQUISHED EVEN THOUGH YOU ARE A MAN; REMEMBER THOSE MOMENTS WHEN I LED YOU AND YOUR EXALTATION; REMEMBER WHAT IT WAS THAT DREW YOU BACK AND WHAT IT WAS YOU LOST RENOUNCING ME; REMEMBER MY OPEN WOUND, REMEMBER MY SMILE; FOLLOW ME.” Another stand-out work is Iannone’s A Fluxus Essay and An Audacious Announcement (1979), a totem emitting faint sound with a pink face and on which an essay about being a Fluxus outlier is scribbled. “I am she who is not Fluxus…” Iannone writes, rather brazenly summing up what it’s like to be sincerely cared for by Fluxus men, but simultaneously Othered — in other words, to be the periphery of the center.

The 1980s and ’90s saw Iannone’s further use of the staged tableaux of ancient Egyptian paintings and the symbolic, pared down figures of Indian tantric paintings. Mother and Child (1980), a busy red-hued gouache painting on Bristol, borrows the stacked compositional structure of ancient Egyptian works, whereas The Darling Duck (1983–84), a felt pen and ink triptych on Bristol, sees a turn toward the tantric. The central board features two diamond-eyed figures, a man and a woman, twisting their backs to unite in coitus, their legs splayed perfectly in the air as a mirror reflection. Later, in an even more direct reference to Indian mythology, Om Ah Hum (1994) depicts a woman with eight arms with the text “VAJRA GURU” festooned above — a reference to the Sanskrit mantra popular with Tibetan sadhakas.

Iannone continues to live in Berlin and create work in her signature style. Luminous (2012) and Dieter and Dorothy (2007), to name but two examples, combine nude figures and motifs as per her paintings of previous decades. Her 2009 series of small wooden sculptures represent a departure from this format, and feature the romantically entangled male and female protagonists of popular (and not-so-popular) films. Titled “Movie People,” the series depicts the stars from movies ranging from Lolita to the lesser-known Morocco to Brokeback Mountain (one of her rare forays into non-heterosexuality). That Iannone takes her content from pop culture rather than world cultures seems fitting — unlike the world religions Iannone borrows from, pop media represents lofty ideals morphed into the context of the everyday.

Perhaps Iannone’s most compelling work is her practice as a whole, including her biography. Yet she isn’t usually thought of as an artist who lives their practice as per a Beuysian notion of social sculpture — perhaps because she worked during a time when it was not great to be a woman. Take, for example, the work of the Polish neo-avant-garde duo KwieKulik, whose artful documentation of their life together, the life of their son, and the surrounding context of the Polish art scene amid the backdrop of fascist communism was their practice. (Incidentally, it also took decades for KwieKulik to be properly canonized.) Or consider the work of J. Morgan Puett, an artist who terms her Hudson Valley residence, which hosts art residencies, performances, and lectures, and in which she is raising a son, a complex(ity) — a complex, as in a group of buildings on the same site; and a complexity, something untamed and constantly evolving, her life.

For Iannone, it is precisely the subjective, biographical and narrative approach to her practice

that continues to be so revelational. This modus operandi, so respectfully counter to the normal authoritative, self-aggrandizing and pseudo-cerebral voice that still dominates artistic discourse today, is also that which probably sidelined the artist for so many decades. Ironically, it is also one that seems to have led to an ultimately fulfilled life and long-sustained artistic practice.