“Either this is madness, or it is hell.” “It is neither,” calmly replied the voice of the Sphere, “it is Knowledge; is it Three Dimensions: open your eye once again and try to look steadily.” – Edwin A. Abbott, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions

Ah, the obligatory summer reading – every student’s favorite tradition, right? Try to Picture a sixteen-year-old begrudgingly tackling Edwin A. Abbott’s Flatland: confusion and irritation were abundant in those pages. How was a bored teenager supposed to wrap their head around that kind of novel?

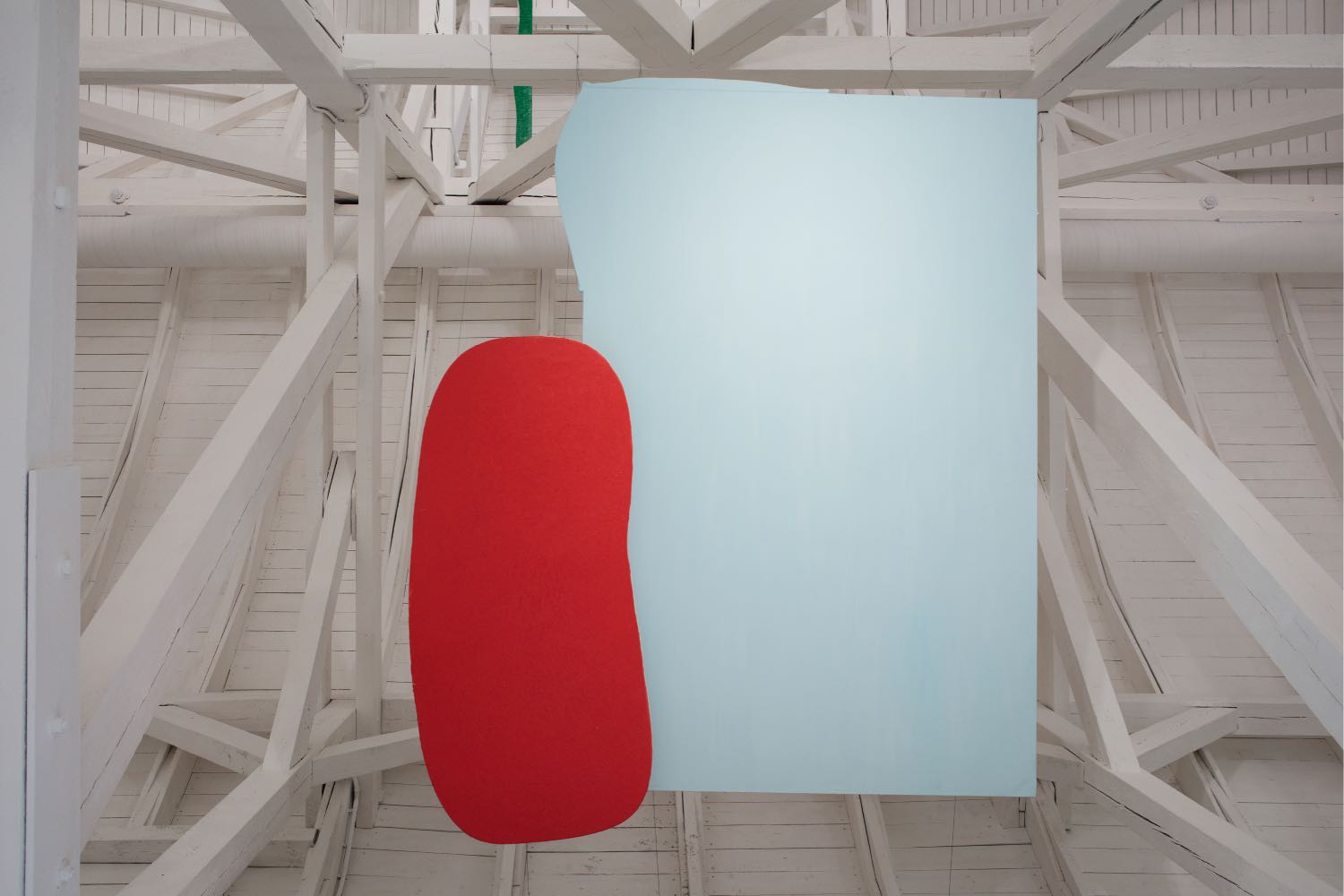

It wasn’t until when – fifteen years later – I found myself strolling through Amanda Ziemele’s solo show “O day and night, but this is wondrous strange… and therefore as stranger give it welcome,” at the 60th Venice Biennale, where she’s representing Latvia. That’s when it finally hit me: the big metaphor that Flatland is.

I guess it’s true that everything takes time. And it’s not a case that time was the first topic Amanda and I touched upon when we talked via Zoom on an April afternoon. The weather in Milan was miserable that day (as it was the rest of the month), but raindrops were the perfect backdrop for our conversation on literature, language, artistic processes, and the great unknown horizon.

Michela Ceruti: So, Amanda, you’re currently living in Jūrmala, right? It’s fascinating how it has evolved from being an extension of Riga to becoming a separate city on the Baltic Sea. Were you born and raised there?

Amanda Ziemele: Actually, I was born in Riga, but my childhood was quite an adventure. After my grandfather passed away, my grandma decided she wanted to live by the seaside. [laughs] Jūrmala’s beach is thirty-two kilometers long. The city consists of a string of small resorts and, over the years, I have resided in several of them.

MC The sea truly has a way of drawing people in, doesn’t it? Jūrmala’s history is quite intriguing because it used to be a popular holiday destination during the Soviet occupation. I was looking at some photographs on Google, and I immediately had this feeling of a place frozen in time. It’s ironic this was my first thought, considering the importance of time as the fourth dimension in your practice. So, I’m wondering how much your surroundings have influenced you and your work.

AZ I would say that living by the sea had — and still has — a deep impact on me. As a child, I spent countless hours every single day at the shore, captivated by the horizon — a timeless presence unchanged since the dawn of humanity — and digging deep in the sand in search of objects with archeological qualities. I vividly remember the winter of 1995 — I was a little child — when the sea froze, stretching endlessly. It felt like you could walk to the edge of the world. The sea, no matter what, remains a constant.

MC I am truly moved by the way you talk about the sea. And for some reason, it reminds me of the final verse of this poem by E. E. Cummings called maggie and milly and molly and may (1956): “For whatever we lose (like a you or a me) / it’s always ourselves we find in the sea.” I know your connection to literature and poetry runs deep, not just in your art but very being. I’ve noticed your exhibitions often feature short poems you’ve written. It’s as if you used words to shape and give meaning to your creations. Is this a deliberate part of your process, or does it unfold naturally as you work?

AZ I am a painter; therefore, I wouldn’t necessarily call myself poet, but rather, I see it as a way to materialize my thoughts; it’s definitely a process that evolves organically as I create. Sometimes I jot down ideas to capture my thoughts and revisit them later. It’s all part of sailing into the unknown, bringing my vision to life.

MC It’s like you’re keeping a travel journal, documenting your artistic journey along the way.

AZ Yes! Sometimes it starts with just a few scattered observations or ideas that I think could become something like the pieces of a puzzle waiting to be assembled. Other times, it’s only a few words that spark a cascade of inspiration. It’s a dynamic process that doesn’t always require putting pen to paper, therefore brush and sticky oil paint feel more adequate. It’s more about allowing ideas to evolve naturally over time, balancing between the spontaneous and the rational.

MC Another intriguing aspect I’ve noticed about your practice is the titles you give to your works. Sometimes they seem to mirror the piece itself, like those showcased at the Venice Biennale — Lemon Peel or Wave. Other times, they take on a life of their own, like in your solo exhibition “Sun Has Teeth” (2023) at the Latvian National Museum of Art in Riga — Unfortunately, Untranslatable, and Glazed Boredom.

AZ To me, titles are just another layer of the artwork, alongside form and color. They can play a crucial role in how viewers interpret the piece and further associations that emerge. I enjoy playing around with words, sometimes knowing the title from the outset and letting it evolve as I work. Translating titles from Latvian to English — or vice versa — adds another depth; it’s not just a process of finding an equivalent word. It adds another dimension.

MC Have you ever found yourself inventing new words?

AZ Absolutely, especially when existing words don’t quite capture what I’m trying to express. There’s this painting Conceptaculum (2018) from my solo show “Fish with Legs” that was on view at the Riga circus’s former elephant stables (2018–19). The word may seem to have resemblances coming from Latin, however it’s not the case; it’s a hybrid. I developed it because of the necessity as a missing link and the additional quality of the work.

MC When you embark on creating a new piece, do you usually have a specific shape in mind from the outset, or does the shape develop as you work?

AZ It’s a bit of both, really. Every piece tends to have its own unique genesis — but it’s not a phrase. [laughs] When I’m working within a predetermined space — like the Arsenale in Venice or the Cupola Hall of the Latvian National Museum of Art — I’m constantly aware of the environment. However, I’m also exploring different forms simultaneously, considering the relation between the scale and size. Take the Venice exhibition, for instance. While I had to be truly prepared for it, the actual shape and structures merged quite spontaneously. I started with simple paper models, unsure of where they would lead. But then, in the midst of the process, I had this moment where I thought, “Could I really manage to develop this unconventional form so it would be stable enough to survive on its own, when almost working against the rules of gravity?”

MC Have you ever found yourself in a situation where you created something for a space — perhaps one you weren’t intimately familiar with — and it just didn’t quite click?

AZ The interplay between artwork and space can sometimes throw up unexpected challenges. I like to think of space almost as a collaborator. In a way, I establish a relationship with space as an actor that has agency. That’s why I often refer to my paintings as having bones — they’re shaped by the context they inhabit. But it’s not a one-size-fits-all approach; each exhibition venue brings its own set of opportunities and constraints. Take, again, the Venice show, for example. While it isn’t a typical white cube space, it’s a former fabric building with its own characteristics, wooden beams and high ceilings. It’s a dynamic process; decisions unfold in parallel, each one influencing the next. And even when a piece has formed itself, it’s still part of an ongoing journey of discovery and refinement.

MC Your philosophy truly echoes the essence of the 1884 Edwin A. Abbott novella Flatland, which delves into the and societal structures of a two-dimensional world. It’s a profound embrace of the unknown, welcoming diverse perspectives and venturing into realms beyond our immediate comprehension — themes that resonate profoundly with this year’s Biennale, don’t you think? I’m particularly fascinated by the title of the Latvian Pavilion’s show, “O day and night, but this is wondrous strange… and therefore as stranger give it welcome,” a quotation from William Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1599–1601). Could you share more about it?

AZ Yes, the title is actually a Shakespearean thread from Abbott’s Flatland. It speaks to the eternal struggle to transcend our limitations as human beings. Whether delving into the complexities of the human condition or questioning societal norms, Shakespeare’s timeless insights serve as a prism through which we examine our quest for understanding. It’s about pushing boundaries, exploring new dimensions of perception, and interpreting the world around us in fresh and meaningful ways.

MC It’s like hitting a mental gym every day, right? Constantly working out those thinking muscles, pushing ourselves to learn and grow. It can be tough and frustrating, but also rewarding.

AZ Totally! It’s like my artworks are also getting their own workout, building up new skills, transforming themselves and the space into a living habitat within the painterly means, searching for balance and questioning the rules of gravity. They all end up with their own little quirks and personalities.

MC What strikes me about your work is how it draws you in, allowing you to explore every angle and uncover the raw essence beneath the surface. It’s like confronting reality head-on, provoking thought and reflection. Do you feel the same way?

AZ Yes. There’s a depth to the work that goes beyond the initial impression of color and shape. It’s playful yet profound, inviting viewers to contemplate the complexities of existence. And in that exploration, there’s a profound understanding of what it means to truly engage with reality.

MC Exactly. It’s that juxtaposition of joy and struggle that resonates so deeply. And I think that’s what makes your art so powerful — it’s not just about aesthetics, but about confronting the human experience in all its complexity.

AZ And speaking of complexity, the journey behind the Latvian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale is a testament to that. It’s like navigating through the unknown, embracing uncertainty, and ultimately discovering new insights along the way.

MC Quite the adventure! Can you tell me more about how the concept for the Latvian Pavilion came about?

AZ Certainly. It all started with a contest in Latvia, where, together with commissioner Daiga Rudzāte of the Indie Culture Project Agency and the curator Adam Budak, we developed a proposal for the project. Interestingly, we didn’t even know the main theme of the 60th Venice Biennale at the time. It was only later, when our project was selected for the Biennale, that everything fell into place. Looking back, it feels like a natural progression, a seamless transition from one phase to the next. It’s funny how things connect sometimes.

MC It’s like the universe has its own way of guiding us toward our true purpose.

AZ Exactly. It’s all part of the creative journey, embracing the unknown and allowing the process to unfold organically. And I think that’s what makes the experience so rewarding — not just the destination, but the entire path we take to get there.