At The Met Costume Institute’s exhibition “Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garçons: Art of the In-Between,” I happened upon two teenage girls who, judging by their accent and dress, were tourists visiting from the American Midwest. Approaching a display of reconstructed motorcycle jackets and extenuated tutus, I heard one ask the other in a tone of aggressive annoyance: “Do people actually wear this?” Yet this was not a rhetorical question. Here she was, examining seemingly impossible garments constructed by a fashion designer who neither she nor anyone she knew had ever heard of. Before the other could form a reply I volunteered my own, “They do. People really do wear these clothes.” I pointed to a mannequin. “Imagine that jacket on its own, and now with a pair of jeans and flats.” Visualizing it on her own body and in the real context of her life, her eyes widened. You could see a look of desire creep over her face as the meaning and potential of the garment began to unpack in her mind. Both nodded and understood.

Rei Kawakubo founded the Comme des Garçons label in 1969 after pursuing a degree in aesthetics from Keio University and a stint as a stylist. When she stopped being able to find clothes she wanted, she began making her own. In 1981 Kawakubo took her collection to Paris and tore the fashion industry asunder. Derived from a uniquely Japanese point of view, her clothes totally opposed the conventions of luxury, beauty and the body of Western dress. In startling contrast to the conspicuous and excessive glamour of the 1980s, Comme des Garçons was cerebral, intellectual, deconstructed, raw. Considered radical at the time, if not anarchical, it was insensitively dubbed “Hiroshima Chic,” with the fashion establishment rejecting it as ugly or, at best, a passing fad. Yet today, Comme des Garçons is one of the world’s most revered fashion houses, and Kawakubo only the second living designer ever to be honored by the museum with a solo show.

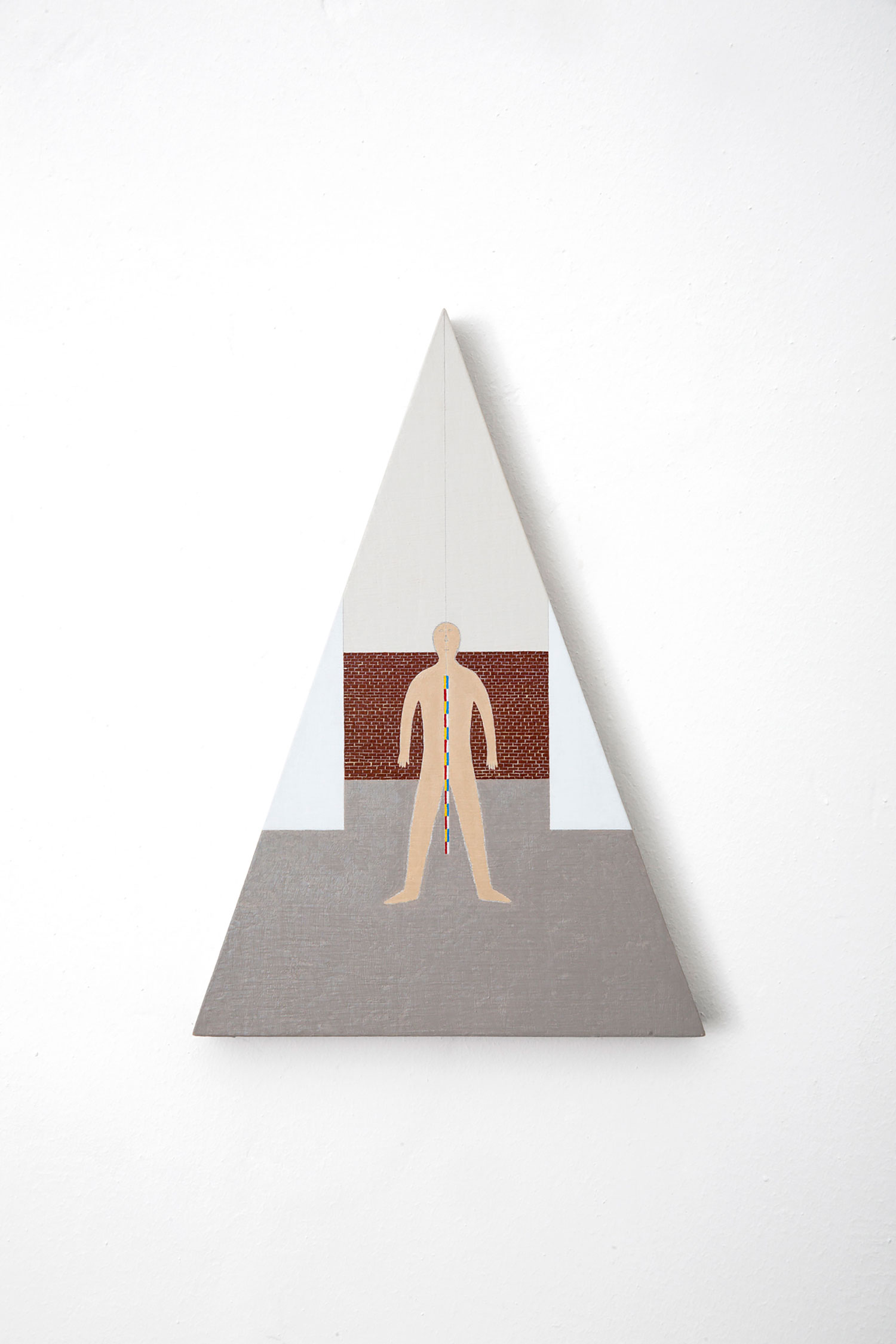

The current exhibition broadly comprises a single white room divided into vignettes by walls, alcoves and platforms, each presenting a selection of clothes framed by opposing binaries: Fashion/Not Fashion, Self/Other, Child/Adult, War/Peace, and so on. The display reflects curator Andrew Bolton’s wit and shows cunning in the way it distills a cacophony of practically indescribable forms, fabrics, textiles and cultural references into their most essential meanings. Each series of words is intended to define abstract meanings that lie between them, made tangible by Kawakubo. This is the idea of emptiness or mu. Though attributed to Zen Buddhism, the concept of emptiness goes back to Japan’s Shinto roots:

The Japanese people devised a mechanism to make some point of contact with the gods dwelling in nature, who were impossible to touch. They put up four thin stakes in four corners and stretch a single rope around them all, creating an empty unit or space. Because empty equals the possibility of being filled, the gods may then find it and enter. […] [T]he Japanese of ancient times embraced the feelings of trepidation and prayer engendered by the possibility that the gods might choose to dwell there. (Kenya Hara, “The Origins of Japanese Design,” in Rossella Menegazzo, Stefania Piotti (ed.), WA: The Essence of Japanese Design, London: Phaidon, 2014)

Mu is pervasive throughout Japanese culture and design. Often misidentified as minimalism, which implies reduction, rather it is the crafting of negative space. Jun’ichirō Tanizaki describes it in In Praise of Shadows (Sedgwick, Maine: Leete’s Island Books, 1977), his seminal text on Japanese aesthetics, as the lighting of a room not for illumination but instead to define darkness. It can even be observed in Manga, in which the hero is drawn with wide eyes and unspecific features so as to allow the reader to envisage themselves in the role. While for most Japanese, mu is a means to simplicity, for Kawakubo it is the permission to risk hubris and define the unknown.

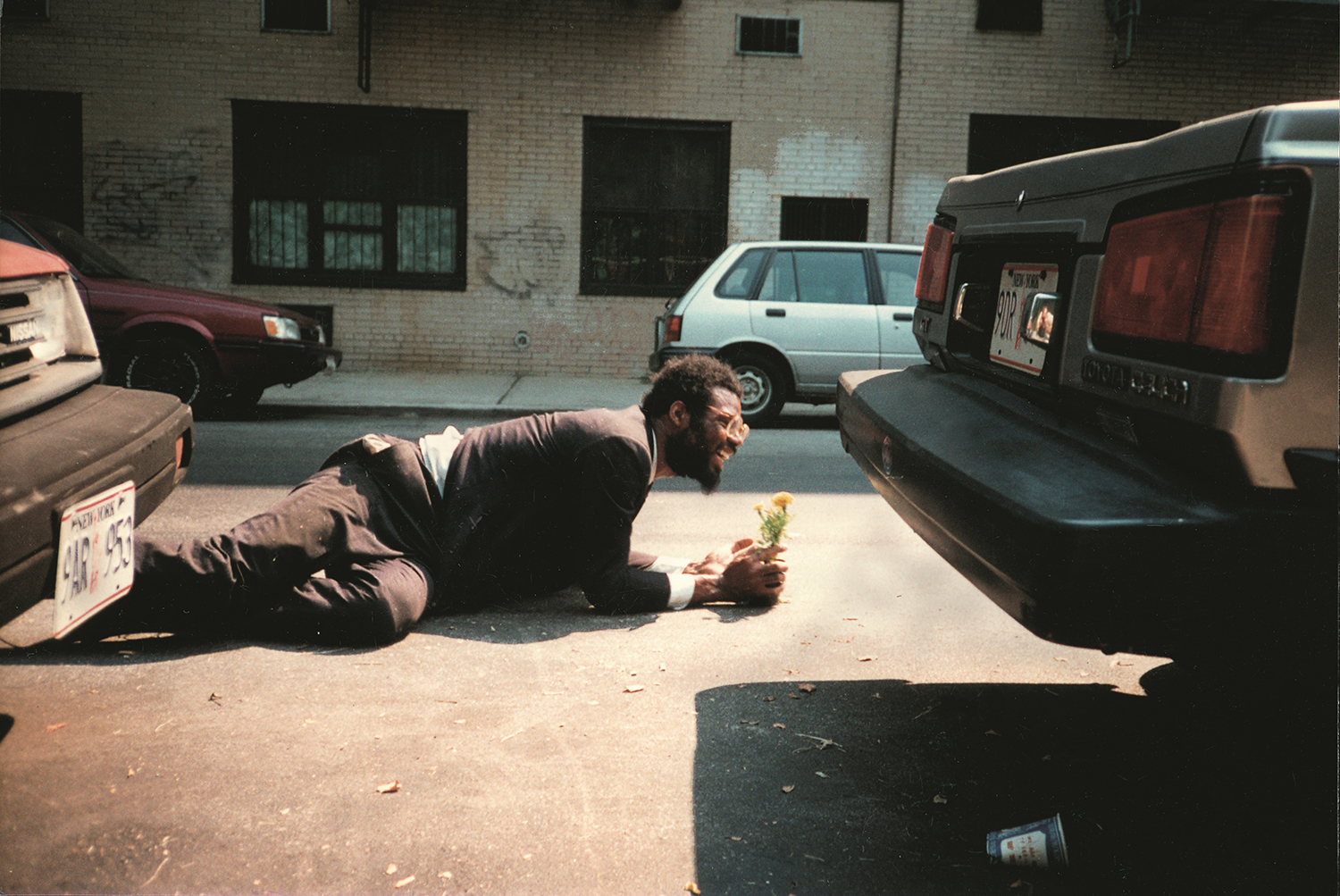

The designer’s unique and independent ethos has fueled an ongoing conversation in the fashion industry over whether or not her clothes are in fact art. Bolton appeals to this conversation by showing the most audaciously whimsical, most lavishly produced and most contrarian selections of Kawakubo’s oeuvre. Visitors are surely astonished, their eyes delighted, and their expectations enlightened by this challenge to fashion’s essential functional purpose. Yet in his appeal to the fantasy of the clothes, he has risked eclipsing their reality. Stripped from all context, perhaps to emphasize the idea of emptiness or even to oblige Kawakubo’s notorious unwillingness to explain her clothes, the garments become that much easier to disregard. A farce. A look that seems unwearable here likely appeared less so in the original collection. An idea too extreme to be believed was perhaps more digestible in the rack of clothes it inspired in-store. The power of Comme des Garçons comes not only from Kawakubo’s efforts but from the wearer’s experience. What makes these clothes radical is that although they are not always recognizable as clothes, they were always meant to be worn.

Finishing up in a gift shop fully stocked with Comme des Garçons wallets and fragrances, the distance between the show’s display and that available to buy is stark. Purchasing my co-branded Comme des Garçons/MET Museum T-shirt, my thoughts returned to the two girls from the beginning. I wondered whether they might not have felt more fulfilled at the Comme des Garçons store in Chelsea. But then they probably would never have gone.