The right to look or the right to look away? Who chooses to look and who chooses to look away? What or who gets seen, and what or who gets silenced or goes unheard in the process? I’ve been ruminating intensively on these questions as part of a book project I’ve been working on over the past year. It’s a project that considers the nature of our encounters with blackness in contemporary art. It tries to understand how the work of certain artists challenges us not merely to look but to witness, and in the process provides a very different understanding of black life in our contemporary moment. It is an active and participatory encounter with what I’m calling a black gaze.

A black gaze does not describe the viewpoint of black people. It is not a gaze defined by race or phenotype. It is a term I use instead to describe a particularly challenging point of view that confronts us with the precarious state of black life in the twenty-first century. It is a gaze that transforms this precarity into creative forms of affirmation. It repurposes vulnerability and makes it (re)generative. In doing so, it shifts the optics of “looking at” to an intentional practice of looking with and alongside. A black gaze does not allow viewers to be passive to its labor or impassive to its affects. It is a gaze that demands work. It demands the work of maintaining a relation to, contact and connection with, another.

The black gaze I am describing should not be confused with empathy. It is not a gaze that allows you to put yourself in the place of another, nor does it allow you to presume you share another person’s experiences or emotions. It’s not about sharing the pain or suffering of differently racialized subjects. It is recognizing the disparity between your position and theirs and working to address it. It demands the affective labor of adjacency. It is the work of feeling done both in spite and because of these differences, and choosing to feel across that difference rather than with or for someone living in very different circumstances.

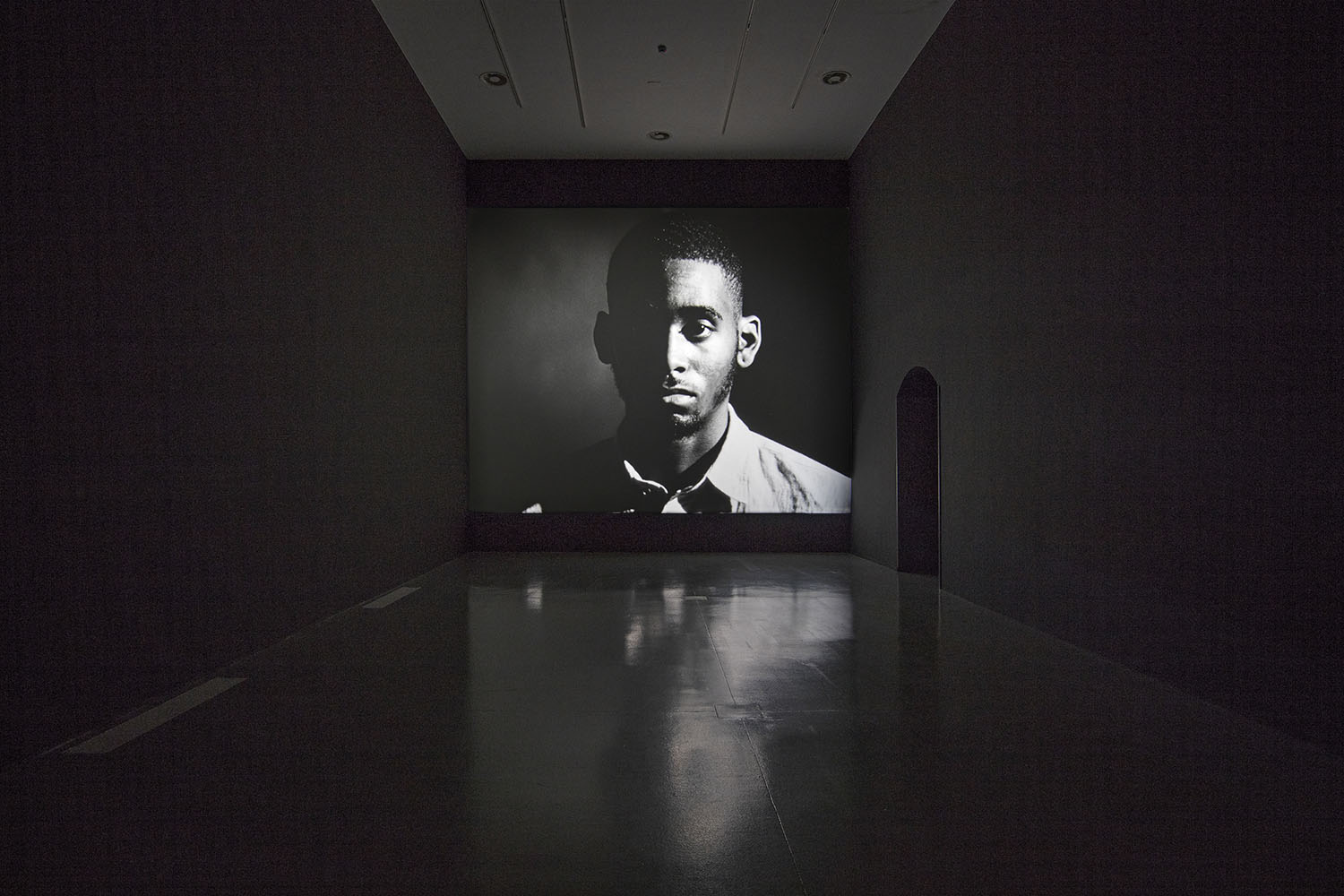

The room is empty except for a massive projector at the center of the room. Its sizable scale dominates and intimidates anyone present in the vacuum of the space. Yet despite its imposing physical presence, its fullest impact is aural and sonic. While the film itself is silent, its visuality is permeated by the rhythmic monotone of a projector that suffuses the space with a rapid mechanical clacking. Its insistent drone amplifies the image it projects and simultaneously engulfs.

The figure on the screen is a black woman with long braids that rest on shoulders covered by a T-shirt. Just below her cropped sleeve, her arm provides the only hint of identification through the tattoo that clads it: Philando. The grainy black-and-white composition of her celluloid presence gives heightened definition to the sheen of her face, the texture of her skin, and the taut weave of her plaits. Her movements are surprising as her almost photographic stillness gradually transforms into subtle, gentle, and affecting motion. Chin held high looking upward; chin bowed with eyes cast downward; glasses skimming abundant eyelashes; absent glasses revealing soulful eyes.

autoportrait (2017) by Luke Willis Thompson is a silent portrait of Diamond Reynolds, whose live Facebook broadcast while seated in a car next to her partner Philando Castile, in the immediate aftermath of his murder by officer Jeronimo Yanez in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, offered a chilling account of one of a seemingly endless series of brutal killings of innocent black men and women at the hands of law enforcement. The artist describes it as an alternate response to this remarkable act of witnessing, as a “sister-image” or second broadcast, “where her survivability is the subject of her performance.”1

Comprised of two four-minute takes of Reynolds filmed in April 2017 in Minnesota and shot in 35mm Kodak Double-X black-and-white film, autoportrait is irreproducible without consent. It must be viewed in the context for which it was created: a darkened room that demands complete immersion and full attentiveness. Straddling the gap between still and moving images, autoportrait was awarded the 2018 Deutsche Börse Prize for photography and was a finalist for the 2018 Turner Prize.

Thompson’s sensuous piece has been celebrated and rebuked. Hailed, on the one hand, as an elegiac reclamation of its subject’s strength, dignity, and humanity; on the other hand, it has been the target of scornful attacks by detractors who view it as an aestheticization of black suffering. Drawing parallels to Dana Schutz’s controversial contribution to the 2017 Whitney Biennale, Open Casket (2016), critics echoed Hannah Black’s condemnation in her open letter to curators and staff where she argued that “non-Black artists who sincerely wish to highlight the shameful nature of white violence should first of all stop treating Black pain as raw material.”2 Citing Schutz’s example, Nick Scammell protested, “Reynolds is known because she refused to be silenced. Yet autoportrait sees her both speechless and distanced into black and white film […] Detached. Disconnected. Inert.”3

As a New Zealander of Fijian heritage, Thompson has described himself as a black artist, albeit not of the African Diaspora. It is an attribution I take seriously, as it positions him in a place of adjacency rather than identity with the forms of anti-black violence his piece so poignantly evokes. It is an adjacency shared by indigenous and diasporic peoples linked by a vicious history of imperialism and colonization that tethers black subjects to Pacific Islanders. It is the adjacency experienced by Diamond Reynolds, sitting next to her partner in a car and witnessing his murder with her three-year-old daughter trying to comfort from the backseat (“It’s okay, Mommy. It’s okay, I’m right here with you.”) and having the composure to attempt to talk down the officer who shot him, while capturing it on a cell phone and broadcasting it live to the world to bear witness to both her loss and her refusal to silence his slaughter.

The projector is even more immense at Thompson’s current solo exhibition at the Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Bergamo, Italy. “Hysterical Strength” is a masterful installation of four of Thompson’s most powerful works: autoportrait (2017), Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries (2016), Human (2018), and a new work titled Black Leadership (2019). As before, the whirring of the projector beckons you in and envelopes you when approaching the space, yet in the course of viewing, its frequency evolves into background ambience rather than foreground noise. It functions as both an accompaniment and a companion to the images whose presence looms so large in the room.

Brandon, grandson of Dorothy. He is the younger of the two men who confront us eye to eye in Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries. The left side of his face is hidden, cloaked by a dark unyielding shadow. His only movement is the infrequent bob of an Adam’s apple, suggesting a reflexive swallow to lubricate the throat of this relentlessly immobile figure. His lack of movement is so profound it could easily be mistaken for a projected still image were it not challenged by the sound and sight of film moving through the projector that serves as its origin. He blinks almost never. Indeed, watching him is like an anxious game of chicken that finds you willing his next blink into fruition.

Graeme, son of Joy. Like his filmic sibling, the expressionless, direct gaze of this second man is also held for five long, uncomfortable minutes. His face is illuminated more fully than the other, as a slim crescent of shadow rests lightly on his right cheek and forehead. Like the man whose image precedes him, his movement is scant, albeit more easily perceptible. It is a slow blink that, once completed, subtly transforms his expression as his eyes narrow into what becomes a quiet, probing glare. The effort required by his diligent intention not to move is evidenced by a periodic flutter of the eyelids, which seem to strain at being held so unnaturally long ajar. His only other movement mirrors his predecessor when his lower lip retracts reflexively to moisten a dry mouth produced by prolonged stillness.

Each of these twinned, 16mm, black-and-white portraits are single takes of two black British men who lost maternal figures at the hands of London’s Metropolitan Police. Cherry Groce, grandmother to Brandon, was shot and paralyzed in 1985 and died later of complications from her injuries in 2011. Her shooting triggered the Brixton riots of 1985. Joy Gardner, mother of Graeme, was killed in her home in 1993, when officers, attempting to arrest and deport her, gagged her by wrapping thirteen feet of surgical tape around her head and face. Unable to breathe, she suffocated then collapsed and died four days later of cardiac arrest.

While the filmic techniques that so powerfully frame Brandon and Graeme intentionally replicate the formal qualities of Andy Warhol’s iconic “Screen Tests,” they produce a gaze very different from the celebrity-hungry white gaze of their predecessor. They expose us to the unrelenting, full-on gaze of black loss that inverts the gaze of the camera by requiring us to be looked at and scrutinized. It challenges viewers to reflect, in the absence of words, on what its protagonists might be thinking, feeling, or seeing in us. It requires us to stand still and dare to be looked at, and to hold and return the gaze of trauma of another. In doing so, they refuse to allow us to look away.

Diamond, partner of Philando, mother of Dae’Anna. Viewing her again in the context of “Hysterical Strength,” the differences between her and her fellow members of this unlikely chorus of witnesses to black negation register initially through mundane and minute details. She is adorned with carefully chosen objects: a sparkly choker, a chain dangling around her neck, lip gloss, earrings, eyeliner. Unlike the men featured in Cemetery, she is not still. She blinks frequently. She moves sparingly but regularly. She breathes visibly, heavily, with the weight of deep reflection.

Unlike her black British kindred in grief, she does not look into the camera. She refuses our gaze and directs it elsewhere instead. Her wistful half-smile tells us that despite her willing participation in the filmic dialogue in which we now partake, her interlocutor was never intended to be us. When she mouths words we cannot hear and wags her head rhythmically; when she closes her eyes, pauses, presses her lips together, as if to hum: we must ask not what words does she speak, but what words would ever suffice? We must ask not to whom is she speaking, but what gives us the right to be privy to a monologue whose grief so fundamentally exceeds words?

While she never eyes us directly, the black gaze of Diamond Reynolds captured so powerfully in autoportrait demands quiet yet arduous labor. It demands we partake of the labor of listening to her quietly enthralling image. As Scammell rightly emphasized, Reynolds’s act of defiance was her refusal to remain silent. Yet autoportrait renders her neither speechless nor silent. In Thompson’s carefully constructed image, Reynolds delivers a devastating critique through a resounding frequency of quiet that wrests our undivided attention.

Neither a gaze of identity or empathy, the black gaze that emerges in autoportrait produces discomforting forms of labor that refuse to position white spectators as the subjects of its gaze. It is a gaze that centers the black subject and inverts dominant definitions of “the gaze” that focus on white male desire as the privileged, if not exclusive, perspective of cinema. It reconfigures this dominant gaze by exploiting white exclusion from and vulnerability to the opacity of blackness, in the process demanding a very different kind of labor of its viewers.

Far from the satisfaction of identification with someone less fortunate, less secure, or utterly precarious, a black gaze demands that we feel the discomfort of being better off and doing the work of making that discomfort generate a different outcome. It requires us to feel beyond the security of our own situation to cultivate instead an ability to confront the precarity of less-valued or actively devalued individuals, and doing the ongoing work of sustaining a relationship to those imperiled and precarious bodies.

The haunting chorus of black gazes assembled in “Hysterical Strength” is in fact a collaborative portrayal of quiet refusal — a refusal to be silenced or to accept the status of disposability. It is a refusal to accept words or speech as either adequate or commensurate to the gravity of their losses or the monumentality of the crime of devalued black life. autoportrait, in particular, forces us to engage with a black woman who overwhelms us through her reserve, control, and containment. It forces us to reckon with the everyday labor that black women have mastered since captivity — carrying loss with dignity, mourning in plain sight, and at the same time refusing to capitulate to the mundane regularity of black death.

Truth be told, a silent portrait of any black woman is categorically unbearable. Our refusal of words is inevitably embraced as an invitation to impose a narrative that we have neither authored nor authorized. Set against the backdrop of the story Diamond Reynolds refused not to tell, why do we demand to hear her tell it again? Why do we expect or demand her to repeat it or tell it differently? Why is this account of it, without words or speech, but delivered instead through subtle gestures that have an affective power that exceeds words, not enough?

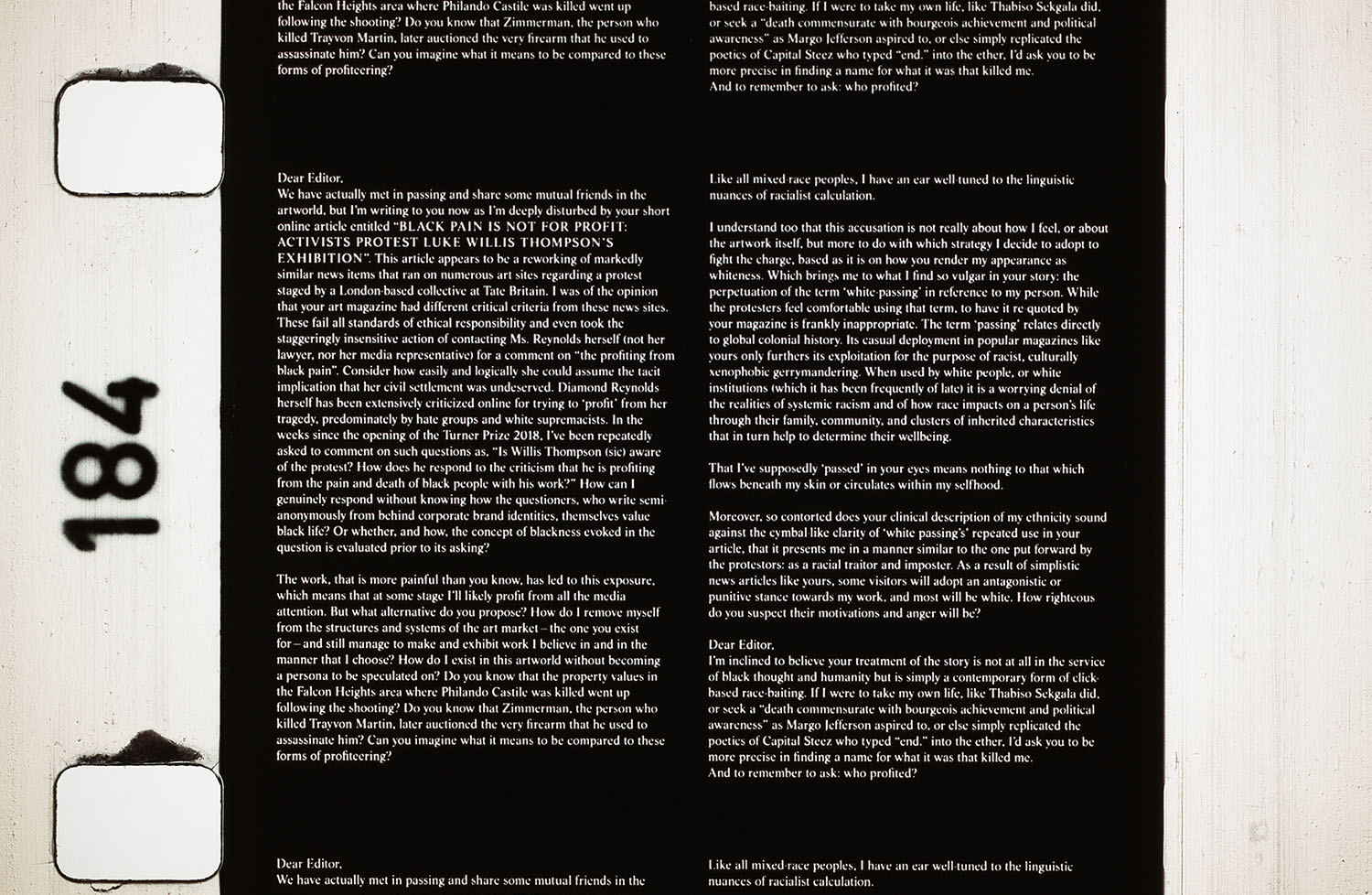

In a second gallery connected to the first, a textual supplement screens alongside the looping still/moving images in the main gallery. Black Leadership, Thompson’s most recent work, is disorienting in its three-dimensional depth. The text flickers and floats as if suspended in air rather than projected onto the wall. It is the artist’s own quiet but deeply resonant rejoinder to many of the questions I have posed thus far.

The floating text is a letter addressed to an art journal editor. The letter is pointed and direct. It urges reflection on comments published in the pages of the journal and demands recognition of their destructive force and implications. Profiteering is the withering accusation to which the letter’s author, Luke Willis Thompson, responds: profiting through art by exploiting black pain and suffering. But is it profiteering or a refusal to remain mute? Is the silent but searing presentation of this trio of witnesses to black negation rendered as a work of art an act of exploitation or is it, as I would argue, an act of refusal?

Yes, it is an act of refusal. It is a refusal to be complicit in the silencing of black pain and suffering, and a refusal to impose words on the indescribable. It is a refusal to depoliticize the space of the gallery or to assume the art world is removed from the politics of black fungibility. It is a refusal that forces us to do the work of reckoning — both inside the gallery and beyond it — with our own culpability with the infrastructures of anti-black violence that pervade every space, regardless of whether we acknowledge it or not.