MohammedKarlpolpot was born in Paris on October 10, 1999. The brainchild of Adel Abdessemed, MohammedKarlpolpot is an imaginary character whose name brings together some of the ideologies that have shaken the West and the East — prophet Mohammed, philosopher Karl Marx and Cambodian dictator Pol Pot. MohammedKarlpolpot is an über-father, a paternal figure who embodies “different epitomes of power, a trinity condensed in a word,” as the artist describes it. Maybe MohammedKarlpolpot is also an exorcism, a way to name evil and thus wish it away. Certainly it is a sign of our times if an artist, instead of creating a joyful, sensual alias such as Rrose Sélavy, or splitting into two in the case of Alighiero and Boetti, is forced to give birth to a monster like MohammedKarlpolpot.

Abdessemed himself is no stranger to reinventing his own identity. Although very young, he has already lived many lives and has had close encounters with the monstrosities of ideology. Born in Algeria in 1971 to a family with Berber origins, Adel grew up in Batna, the capital city of the Aures province, not far from the desert and Atlas mountains. The history of Batna is closely tied to that of the colonization of Algeria and to its fight for liberation. More recently the city was the theater of one of the fiercest Al Qaeda attacks.

It was to run away from the escalation of violence that exploded in Algeria after the assassination of President Boudiaf — and which, over the years, would lead to the death of at least 250,000 civilians — that, in 1994, Abdessemed left Algiers, where he had moved to study art, and came to Lyon, where he enrolled at the academy so that he would not have to live underground. After spending five years in Lyon, where he completed some of his early works, Abdessemed moved to Paris. From there he began a series of pilgrimages to capitals worldwide, from New York to Berlin, then back to Paris and again New York. Told this way, his life and that of his wife Julie seem to follow the rather worn-out cliché we have all grown accustomed to through the rhetoric of globalization in the ’90s. Yet, unlike many artists of that decade, Abdessemed experienced exile not as a free choice but as a forced lifestyle: being a clandestine is not some comfortable metaphor, but a harsh reality. Geography is not a space of infinite possibilities, but rather a series of boundaries and obstacles.

Between the ’90s and the current decade of the 2000s we have witnessed the opening of an unbridgeable gap between artists who believed in the possibility of a peaceful integration, United Colors of Benetton-style, and those who have come to think of the world as a space of conflicts and clashes. Abdessemed of course belongs to this latter group: “Today,” he says, “there is no more atlas […] we are all caught up in a cyclone.” And truly, it is as though Abdessemed’s whole oeuvre were spinning on itself, out of control — nervous, restless, propelled by frantic impulses and peopled by characters seized with fits of hysteria. His videos are short, tight, torn more than edited, repetitive and obsessive, often only a few seconds long. His sculptures, photographs and videos portray skeletons, wild beasts or slain pets, plane carcasses and burnt cars. In Abdessemed’s work there is no paradise possible. There is no nostalgia and no longing for a return to one’s own origins: as he says, he is “not a postcolonial artist” for he is “not working on the scar and not mending anything.” He might miss his mother, but he does not miss his country.

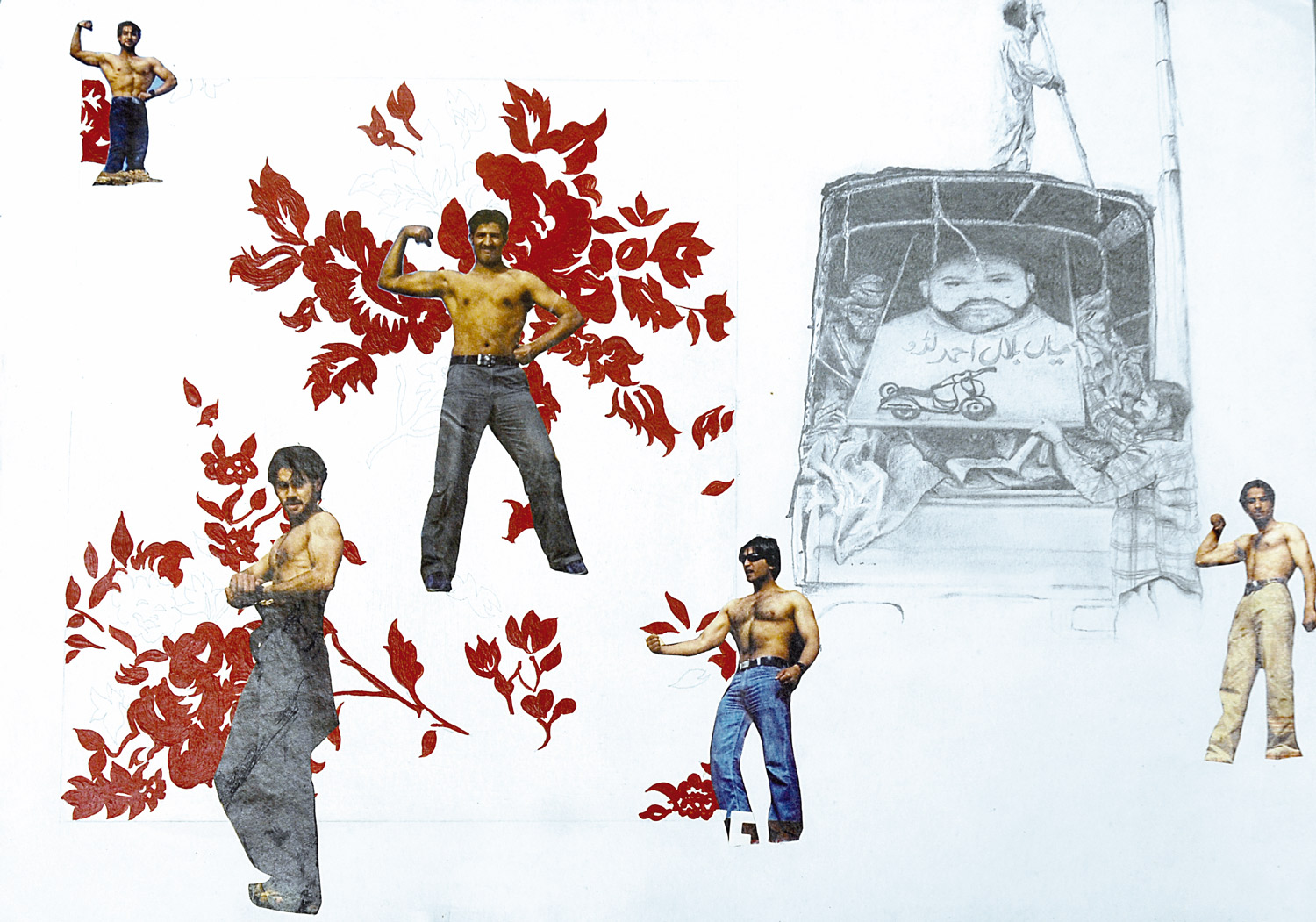

Indeed, in Abdessemed’s work, the sense of belonging to a particular nation — which, in his view, amounts to a form of ideology — is often embodied not by a motherly image, but rather by a father figure, a male character who awkwardly carries the full weight of authority, which Abdessemed tries to erode by subjecting it to simple and radical transformations. In the video Joueur de flûte (1996) — one of his earliest works — the imam of Lyon’s mosque plays the flute, posing naked against a neutral background. The image’s construction reminds us of the presumed objectivity of an anthropological film of some primitive ritual. Abdessemed appropriates and reverses the gaze of the ethnographer, playing with stereotypes and cultural assumptions. The protagonist’s nudity is indeed a dramatic violation of the imam’s authority: the image is not an allegory of communion with nature and with oneself — it’s not the myth of the bon sauvage who lives naked and free in some distant and foreign land of prosperity. It is instead a much more complex and twisted icon, based on a complicated negotiation and resulting in a transgression of personal and religious beliefs. In a similar manner, the video Trust Me (2007) stages a conflagration of nationalism, religious fanaticism and schizophrenia that is both humorous and deeply discomforting. A character endowed with sharp, vampire-like canines chants a litany consisting of fragments of various national anthems. The actor — composer and singer David Moss — bursts into a reckless ranting that is reminiscent of the free flow of words uttered by a patient during an acute fit of glossolalia. In Trust Me, nationalism is seen as a form of pathology, a hysterical linguistic explosion that makes no sense.

In Hot Blood (2008), David Moss, this time hiding behind a clownish red nose, shouts and screams: “I am a terrorist. You… are… you… I… you… am I… am… I… am… I… a terrorist? You are… are you… Am I a terrorist?” His voice is broken by sudden laughs and manic spasms. It is again some kind of disturbed behavior, this time masked as carnivalesque irreverence, which exposes our fears in all their dark, incomprehensible irrationalism.

Hot Blood also stages another typical feature of Abdessemed’s work: his tendency to tackle current events — such as terrorism, violence, repression and other uncomfortable issues — while omitting a clear ethical position. Abdessemed is not a moralist; he is not interested in separating good from evil, which does not translate into a neutral or detached attitude. On the contrary, Abdessemed’s whole work is based on “taking a stand, because in my heart I detest neutrality.” His positions can be sometimes troublesome and difficult to share: they are romantic ideals, often irrational. “I plunge into the dark,” the artist has said. “I use passion and rage.”

Abdessemed shares this form of public indignation with other artists who have emerged in recent years, and who are embracing a raw aesthetic to which they associate a complex spiritual dimension and a new form of humanism. Artists as diverse as Pawel Althamer, Phil Collins, Sharon Hayes, Artur Żmijewski and, in some respects, also Thomas Hirschhorn, have rediscovered the potential of rough, poor materials in dealing with the great tragedies of our history. Each of these artists could, in his and her own way, subscribe to the words of Abdessemed, who claims to be “an artist of acts, not a conceptual artist,” and they might also partake with him a “mad, deep love for our humanity.”

With Althamer, Collins, Hayes and Żmijewski, Abdessemed also shares a complex relationship with the practice of performance: Abdessemed’s work often develops from a gesture, an event that is then preserved in videos or photographs. The artist prefers not to use the word performance to describe his works, because he sees it as too strictly linked to economy and stock exchange quotations. He prefers to talk about “acts.”

Abdessemed’s works have all the swiftness and dexterity of a criminal act, and as such they often take place on the street. In the photograph entitled Kamel (2005) the artist portrays himself as he gets robbed by another North-African, while in the “L’Atelier” series, he stages a peculiar street theater, populating the sidewalks of Paris with exotic animals and alien creatures. In Mes Amis (2005) the artist’s wife takes a stroll down the block while hugging a skeleton. In Sept Frères (2006) a herd of wild boars runs amok among parked cars. In other images, a donkey jolts and kicks, and a snake gets crushed by the artist. In what is no doubt the scariest photograph of the series, Séparation (2006), the artist slowly approaches from behind a lion let loose in the streets.

The images in this series were all, without exception, taken without authorization, and thus can be read as allegories of the status of the illegal immigrant, with whom the artist seems to identify. But they also participate in a tradition within the history of contemporary art, which visualizes the city as a place of magical encounters and sudden revelations, a tradition that starts from Surrealism, continues with Situationism, and finds one of its most recent expressions in the walks of David Hammons, whose art seems to spontaneously harmonize with Abdessemed’s.

While Hammons kicks the bucket on the streets of New York, Abdessemed stamps on the pavement, crushing Coke cans and microphones. The act of crushing something under his heel is a recurrent image in Abdessemed’s work: the bare foot against the asphalt of the road is a gesture of primary violence, as if he wanted to go through the sidewalk. “Under the pavement, the beach,” the Parisian students loved to write on the walls in 1968. Abdessemed, instead, apparently wants to remind us that under the asphalt crawls nothing but violence, slow and menacing as a snake, unpredictable as a wild beast. Hidden in the streets of Paris, hardly concealed, now creeps the African continent. And it’s not the domesticated, psychedelic Africa of Raymond Russell: it’s the violent, brutal darkness of Joseph Conrad.

In fact, Abdessemed’s Africa is not even the one we read about in novels, but that of the urban guerrilla: the Africa of the wretched of the banlieue. Abdessemed’s clay sculptures from the series “Practice Zero Tolerance” are cast directly from real cars vandalized in Perpignan, during that same season in hell that would set Paris on fire at a rate of more than 1500 vehicles destroyed every night.

Means of transportation are often broken down into pieces in Abdessemed’s work. In Bourek (2005) a plane curls up like an old carcass fallen from the sky. In Queen Mary (2007) the famous English transatlantic ship is reduced to a tin tub. If art in the ’90s was a celebration of nomadism, Abdessemed’s art tells us about the impossibility of traveling, or about trips that end with tragedies and corpses. In one of his most famous works, Habibi (2004), the artist establishes a shocking similarity between flying and death: a giant skeleton stretches its arms and legs and takes off, propelled by a jet engine. Leaving is like dying a little, the French say: today, when stepping on a plane, those words sound much more frightening.

Cat eats rat — as simple as that. Abdessemed likes his images to be brutal, raw, as in Birth of Love, 2006, in which a feline devours a mouse. Abdessemed’s work is based on a convulsive beauty: his videos are agitated by repetition and hypnotic sounds pulsating at a syncopated rhythm that is absolutely personal and quite infernal. Hearing the humming and buzzing of Abdessemed’s videos you often wonder if that is the sound of hatred.

In Don’t Trust Me (2008) — a suite of eight videos in which animals die under the blows of a sledgehammer — the sound becomes almost unbearable, more difficult to sustain than the images themselves. And again it is the penetrating noises made by fighting animals in Usine (2009) that are more disturbing than any of the scenes in which different species of predatory creatures live side by side.

Abdessemed’s bestiaries have generated strong reactions and protests in the past. Which forces us to ask a very direct, spontaneous question: why don’t we get just as upset when confronted with images of car bombs exploding in Iraq or missiles falling on Gaza? It is all but a rhetorical question, that helps us understand a basic feature of Abdessemed’s art: as for many artists of his generation, his whole work is on the side of the raw, as Claude Lévi-Strauss would say: it refuses the good manners and sophistication of the cooked. After years of highly polished images and post-production tricks, after decades of speculation about societies of the spectacle and media studies, a new generation of artists is turning to an immediacy that seems unbearable, because it is unfiltered, brutal and sincere.

Abdessemed’s art, like that of many of his traveling companions, turns its back on the high production value and media savviness that have prevailed in the last decades. This is not relational aesthetics; it is asymmetrical realism.

There is also a spiritual tension in Abdessemed’s work, a sort of pantheism that again seems to point to similarities between Abdessemed and artists such as Pawel Althamer. Abdessemed is openly critical about the three main monotheist religions, but even as he refuses these positions he seems to return to a pagan religiosity, which may reach back to his Berber origins.

Abdessemed seems to believe in a totemic spirituality. His works with animals resonate with memories of sacrificial rituals and primordial powers. True, Abdessemed does not want to go back to magic — on the contrary, he firmly believes that totems, like taboos, must be broken, because art is first of all “a means of liberation from oneself.” From the wine fountains he created almost ten years ago, to the naked dancers of Passé Simple (1997) and Joueur de flûte, all the way to the cannabis sculptures he made in 2000 and 2008, the themes of intoxication and loss of control run throughout Abdessemed’s work like a gout of hot blood.

Ecstasy is the ultimate aim of his art — an escape from one’s own body, a way of being beside oneself, which can be reached through sex — as in the video Real Time (2003), in which couples of strangers mix in a scene of group sex — or by hanging from a helicopter, from the wings of God, as the title of his last video recites. The fact that an atheist should talk to us about God is only an apparent paradox, and certainly far less embarrassing than those who kill in the name of God.