Performance of a Massacre (2016), a recent performance piece by Yan Xing (b. 1986, China) at Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, unfolded in the absence of its protagonist. It started with an announcement saying that the scheduled performance, in which “thirty-seven victims of a massacre will spread throughout the museum,” was canceled “because of the artist’s sudden departure.” A lively discussion about what might be the real reason for the work’s cancellation was then triggered among seven participants, including the Stedelijk’s chief curator, an actor from the scheduled performance, a museum educator, an art historian and an art critic. Their speculations gradually turned into a ruthless debate, in which they fiercely questioned each other’s motives, professional ethics and morality. Thus a bloodless conceptual massacre was performed in a way that subtly resonates with the plot of François Ozon’s film 8 femmes (2002), in which a father’s mysterious death causes bitter recrimination among eight female family members as they reveal each other’s filthy secrets.

The absence of the father is central to Yan’s first notable work, Daddy Project (2011), in which, facing a white brick wall, the artist gave an autobiographical speech about his fatherless childhood. He spoke about his biological father whom he never met, his legal father who was irresponsible and violent, his mother’s many boyfriends whom he was forced to call father, and his many boyfriends whom he considered father figures. From behind, the audience was not able to see Yan’s countenance; they could only assess these intricate relationships without catching sight of the emotional results they brought about. During the speech, the artist said that his father was invited to the performance and was supposedly hidden in the crowd. Frequently he attempted to speak to him, though without getting any response. However, that “father” could also have referred to any of the spectators who shared the father’s sins as well as his potential to offer love, pleasure and security. The absent father was not to be accused but to be rediscovered and reconciled with, which became obvious in the artist’s appropriation of an early twentieth-century Chinese ballad called “The Wandering Songstress,” which he intoned at the performance’s beginning and also at its end: “At the edge of the sky and the end of the sea, I look for someone who understands me… I am the string and you are the pin. My lover, once together, nothing else can get in.”

Traces of that intricate father-son relationship can also be witnessed in Yan’s relationship to art history. “In terms of my exposure to the arts and literature, all my role models are Western,” he mentioned in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist [Recent Works, Beijing/Lucerne: Galerie Urs Meile, 2013, p. 85], but “there aren’t many individuals that can be called a hero and who strongly influenced our generation.” The appropriation of historical works of Western art and literature has been evident in his own works. However, most of those historical figures, such as Pier Paolo Pasolini, Jean Cocteau, Éric Rohmer and Edward Hopper, to name a few, were more akin to irresponsible fathers who left a heap of broken images for the artist to inherit. In the video piece The History of Fugue (2012), Yan mimics the postures in Robert Mapplethorpe’s seven classical photographs of black male bodies, claiming that each posture signifies “a murder of its predecessor.” He stands in front of the camera exhibiting his naked body, proud but nervous, fresh and clumsy, like a new monarch showing off his power after the original one was deposed. However, that “original” could never be truly absent given the artist’s attempts to mimic the postures in Mapplethorpe’s original pieces. The work reveals an ambivalent obsession — replacing an art-historical father by continuing the work he began. Lenin in 1918 (2013), an installation work named after a Russian film from 1939, presented a neatly decorated exhibition space in which a number of copies of modern masterpieces were displayed together according to an eccentric logic invented by the artist. Among them were slightly distorted versions of easily recognizable works by Cézanne, Matisse, Malevich, and Brancusi, as well as several photographs by Theodor Hey, a supposedly lesser-known twentieth-century photographer. Interestingly, those photographs were actually taken by Yan himself; looking closely at one of them, the name Yan Xing can be seen carved on a white brick wall. In this way, Yan smartly presents his work in the context of the modern avant-garde by appropriating the name of an artist who is absent from the accepted narrative of that history. “It is about our psychology after our modernist patricide for progress and our understanding of legacy,” the artist told Obrist. The work emerged from Yan’s intensive study of art history, but some “realistic but not necessarily real” evidence was also fabricated in order to create a narrative in which the artist and his predecessors could coexist.

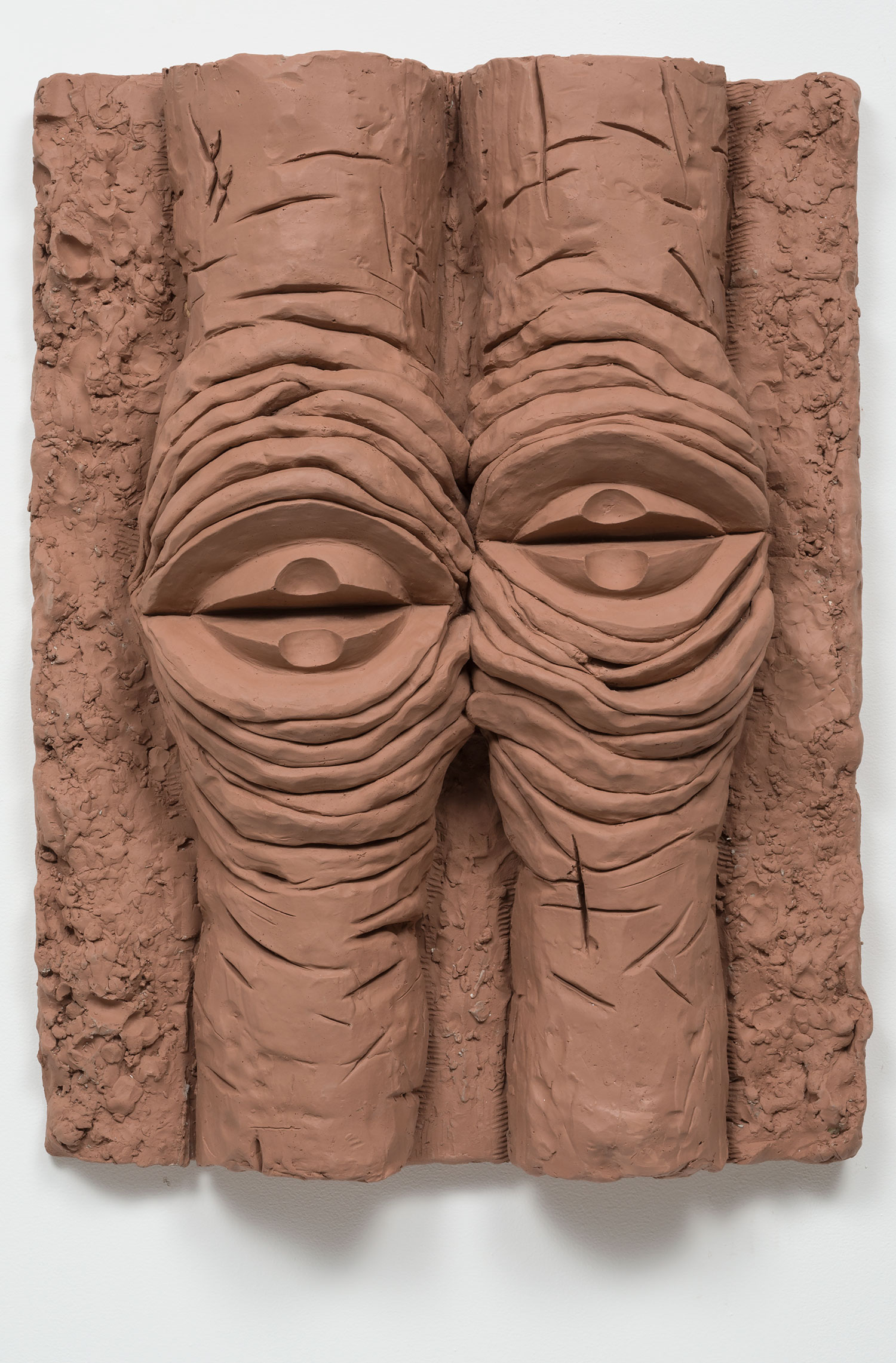

Yan’s art is strongly related to narrative, which undoubtedly benefits from his interest in literature since childhood. “To ‘inherit,’ to ‘spread’ or to ‘pass on’ a story has always appealed to me,” he said in an interview with Jérôme Sans. [China: The New Generation, Milan: Skira, 2015, p. 183] Literature has its own sinuous path that refuses any reductive interpretation; in the same way, each story in Yan’s work concerns the artist’s intricate relationship with others, which exceeds any descriptive language. In La part du feu (The Work of Fire, 1949), Maurice Blanchot points out that our language has the power to negate the actual concrete thing for the sake of the idea of the thing; instead, in literature, words do not transform the negativity of language into the positivity of a concept, but stubbornly preserve its demand to “experience the absence as absence.” In L’espace littéraire (The Space of Literature, 1955), Blanchot further articulates the dialectical relationship between words and absence: “Words, having the power to make things ‘arise’ at the heart of their absence — words which are masters of this absence — also have the power to disappear in themselves, to absent themselves marvelously in the midst of the totality which they realize.” [The Space of Literature, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982, p. 43.] Yan Xing is skilled at making up dramatic scenarios with absent characters. In the performance piece The Sweet Movie (2013), a crew set up in Venice for a pornographic film shoot, but one of the two actors cast in the film was absent, so the crew had to spend the time continually shooting details — the fake-orgasm face, the undulating body parts — with the only actor who was present. The absent actor made himself the true protagonist in the scenario merely by being absent. This also implies a transgression against the power structures of artmaking: it corresponds to what the artist had done in Performance of a Massacre, in which the curator, the art historian, and the art critic, who are always considered superior to the artist in the system of power relations in the art world, were manipulated by the artist, following the script about his absence. But behind the scenes, the real things that mattered were the artist’s masterful social skills and his keen ability to communicate and persuade, traits that were tacit in the performance they brought about.

However, absence also signals an act of extreme passivity. To some extent, to make art is not to create from a position of authority but to do so in the absence of power. In the process of creating an artwork, and in the journey of pursuing success and enjoyment in the art world, risks of failure and the inability to satisfy the other are always latent. The young man wearing a white shirt, an image that frequently appears in Yan’s work, indicating a taste for male sexiness and decency, also implies a fear of disdain or disfavor. That is made implicit in works like The Story of Shame (2015), an installation consisting of a series of photographs about shame: one photograph shows a neatly dressed young man wetting his pants, while another one reveals the protagonist’s unrequited foot fetish. (In the installation some of the photographs were partially hidden behind wall partitions). In Thief, a video piece made the same year, a well-dressed man hides in a corner. He holds a small knife, fretfully scanning the street and rehearsing a stabbing gesture, but no targets for killing emerge. In a later sequence of the same work, two young men in white shirts squat down before the camera. One feeds the other an oyster that he has shucked carefully with a knife and cradled in a silk napkin, only to witness his companion spit the food into his palm in disgust. After those metaphors of fear of loss, we see a close up of a horse in a sunny field, its sinewy legs and huge penis potent symbols of virility — but read via psychoanalysis, the animal could also be suggestive of Sigmund Freud’s case of Little Hans, in which a four-year-old boy’s fear of horses was diagnosed as a manifestation of his fear of his father, and men in general.

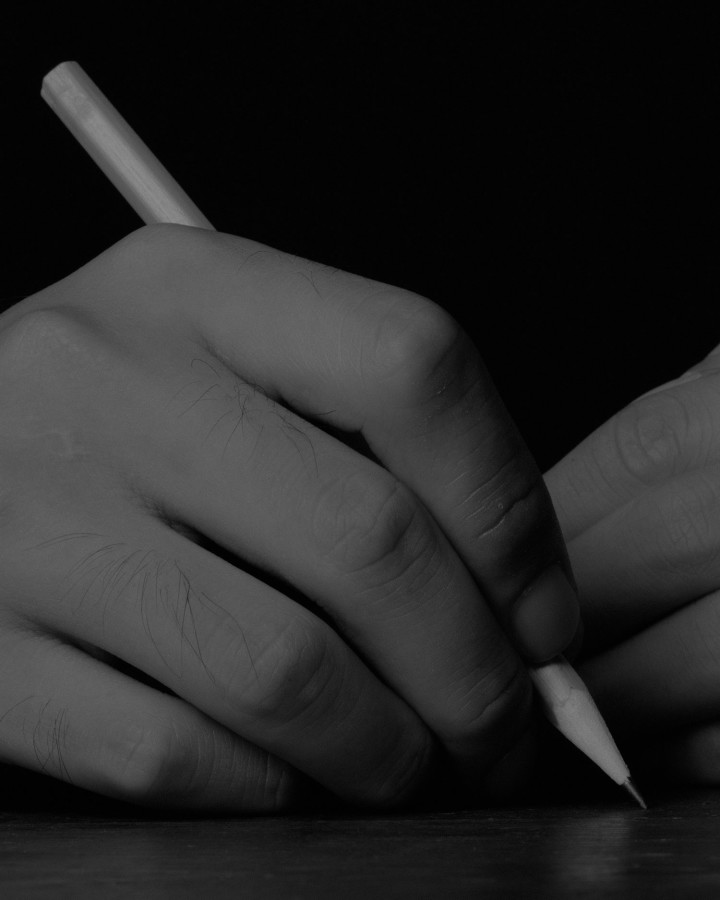

Sexy (2011), an early video piece, epitomizes the artist’s relation to the other both inside and outside the art world. In a precarious canyon, the artist repeatedly forces himself into an erotic state of mind in order to masturbate, but such brutal and primitive attempts are interrupted again and again by the hostile natural environment — the freezing temperature, a howling gale and falling rocks. Jacques Derrida once argued that writing and masturbation are both supplements to nature. In Of Grammatology (1967) he observes that Rousseau considers masturbation a model of vice and perversion, since it “permits one to affect oneself by providing oneself with other presences, by summoning absent beauties,” and thus “one corrupts oneself (makes oneself other) by oneself.” [Of Grammatology, trans. G.C. Spivak, John Hopkins University Press, 1976, p. 153] However, Derrida believes that this alteration does not simply happen to the self. Rather, for him “it is the self’s very origin.” To masturbate in the emptiness of nature where the other is absent, or alternatively, to absent oneself from the art world where the other is excessively present — the two tactics have been deftly employed by the artist to keep making art in various relations with the other.

Yan’s work never directly responds to any prevalent social or political discourses. Instead, it supplements these realities through autonomous narratives. The absence of explicit social concern enables the presence of multiple interpretations in different contexts. In Performance of a Massacre, for instance, the ruthless debate, the scheduled “massacre,” the hint of censorship, the atmosphere of hatred, all point to the present crisis in Europe. Similarly, in Two videos, three photographs, several related masterpieces, and American art (2013), a body of work made soon after the artist moved from Beijing to Los Angeles, photographs of muscular black bodies are juxtaposed with cat-o’-nine-tails whips, alluding to the specter of racism that haunts the United States and even prefiguring the Trump era. Absenting itself from the social milieu, Yan Xing’s work obtains unlimited potential to ask any question, to suspect all dogmas, and to analyze every presupposition. A taste for absence is always essential, enabling his art to maintain the capacity for “inducing meaning without being exhausted by meaning.” That is how Derrida defines great literature.