Intensifying racisms and growing ethno-nationalisms require political answers. We know what has to happen: negotiations, treaties, and policies will have to address these destructive forces in tandem with the ongoing climate catastrophe. Toward what schemas of a flourishing existence should we orient ourselves in crafting these responses? Whose lives are we considering in our deliberations? And as a society, how can we make real the necessary lines of action?

Friedrich Schiller had a reply. He pointed out that our aesthetic activities, which he associated with a sort of play that conjoins reason and emotion and integrates ethical consciousness with desire and bodily inclination, could turn the ideal of collective freedom, which he called “political freedom,” into an actuality.1 Writing in Weimar at the end of the eighteenth century, he devised his answer for a society in which he believed increased compartmentalization had diminished humanity. His solution consisted of a bridging of faculties that had become divided: this process of connection and mediation would transform the ways we think, act, and feel within the social collective. The result would be equality and the spreading of knowledge across classes. Schiller grounded a political process in an aesthetics. He had the happiness of the whole world in the horizon.

Taking a cue from Schiller, my question becomes: What sorts of things do we want to ask from our aesthetic capabilities in view of the hate-mongering mobilizations that are occurring in Western societies against people of color of all genders, women of many ethnicities, races, and classes, sexual/gender minorities, refugees, and immigrants from the Global South? And what can we make of the ideals of collective freedom and happiness? Schiller himself is tricky because his proposed path toward those ideals reiterates problematic exclusions. But the notions of public freedom and happiness remain with us as a calling and a font of promises. In response to this appeal, I ask: With what kinds of strategies can our aesthetic capacities tackle the encounter between violently exclusionary contemporary developments and kernels of joint freedom and shared happiness?

Here, the day-to-day is key, as theorists starting with John Dewey have acknowledged. We inhabit worlds steeped in aesthetics. Extending far beyond works of art, aesthetic norms and forms pervade quotidian existence: we encounter them in the street, in our own and others’ bodily movements, and in the offerings and demands of consumer culture. Corporeal interactions can be welcoming, warming, even enticing. Places like food canteens or ice cream parlors and objects like dresses or drones can attract or repel us when we meet them with our aesthetic desires and distastes. Our prosaic responses to the world put into play our auditory, visual, spatial, olfactory, and gustatory sensibilities. It is then no wonder that aesthetic modes and standards fundamentally characterize our social identities: as white workers, women soccer players, Venezuelan refugees, Chinese citizens of the globe, Kenyan voters, or European nationals. We collaboratively carry out our being and becoming in an aesthetic sphere. Aesthetic experience makes up a significant part of the way we exist as individuals, in groups, and in public life. From the glowing intensity of a dance party and the mournfulness of a funeral to the controlled fury of a protesting crowd, we apprehend social events in aesthetic terms and conceptualize the social order through the aesthetic experiences that it engenders and inhibits.

Pushing this idea further, we find that the social and material relationships we inhabit fundamentally put to work aesthetic meanings.2 Cultural productions bring their imaginative resources to these relationships: artworks can point to junctures where transformations are needed and can incite us to actualize these changes.

The Hegemonic Museum, the first section of Voluspa Jarpa’s multipart installation Altered Views for the Chilean Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale reviews six incidents in world history that celebrate and reclaim identities subjected to repression. Presenting the results of the artist’s research, it mimics the organization of a “regular” museum show. It begins with an instance of cannibalism in the Netherlands, a practice historically attributed to colonized peoples as opposed to colonizing nations. The viewer catches a peek of the murder, flaying, and partial devouring of mathematician and republican statesman Johan de Witt and his antimonarchist brother Cornelis de Witt by a royalist mob in The Hague, in 1672. This episode followed a period of demonization of the brothers (in printed prose, political cartoons, speeches, and satirical rhymes). The crowd proceeded to sell pieces of the victims’ bodies.

Echoing the theme of interlacing mercenary, political, and media endeavors, a different section shows photos and texts relating to the violent overthrow of the socialist president Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala in 1954 through the combined efforts of the United Fruit Company and US government and intelligence organizations. The coup d’état paved the way for a sequence of authoritarian regimes, which undid Árbenz’s land reforms, favored corporate exploitation, and carried out a genocidal campaign against Mayan Indians. In another portion of the installation, Jarpa documents the ethnographic expositions that exhibited nonwestern people for Western audiences throughout nineteenth- and twentieth-century Europe. One segment is devoted to Jean-Martin Charcot’s theatrical display of so-called hysterical women in the Parisian Salpêtrière hospital. Indexing through aesthetic devices the aesthetic operations of modes of gendering, racialization, class institution, and colonial/decolonial agency, Altered Viewsextols and rehabilitates an array of historically suppressed identities.

Jarpa’s work goes further. It ruptures a geopolitical vision that opposes a normalized, appropriately ordered Global North that we can panegyrize to a disorganized Global South that we can vilify. It blocks a lauding of white masculinity paired with a denunciation of modes of being that fall outside that frame. The viewer forges linkages between multiple kinds of oppression and resistance, and between the different situations of the populations suffering or mobilizing them. These linkages place pressure on the social system harboring each historical scenario and on the broader historical setting of which they all form a part. We begin to intuit and wonder about aspects of that larger pattern. Another piece in the pavilion, The Subaltern Portraits Gallery, replaces the traditional spectacle of imperial visual historiography with images of victimized individuals and groups to ask “How can we understand the formation of other bodies and other realities?” and “How can we transcend subalternity without forgetting, in order to build new forms of relationship?”3 The pavilion as a whole calls into question the web of aesthetic relationships that we inhabit with each other, things, and places.

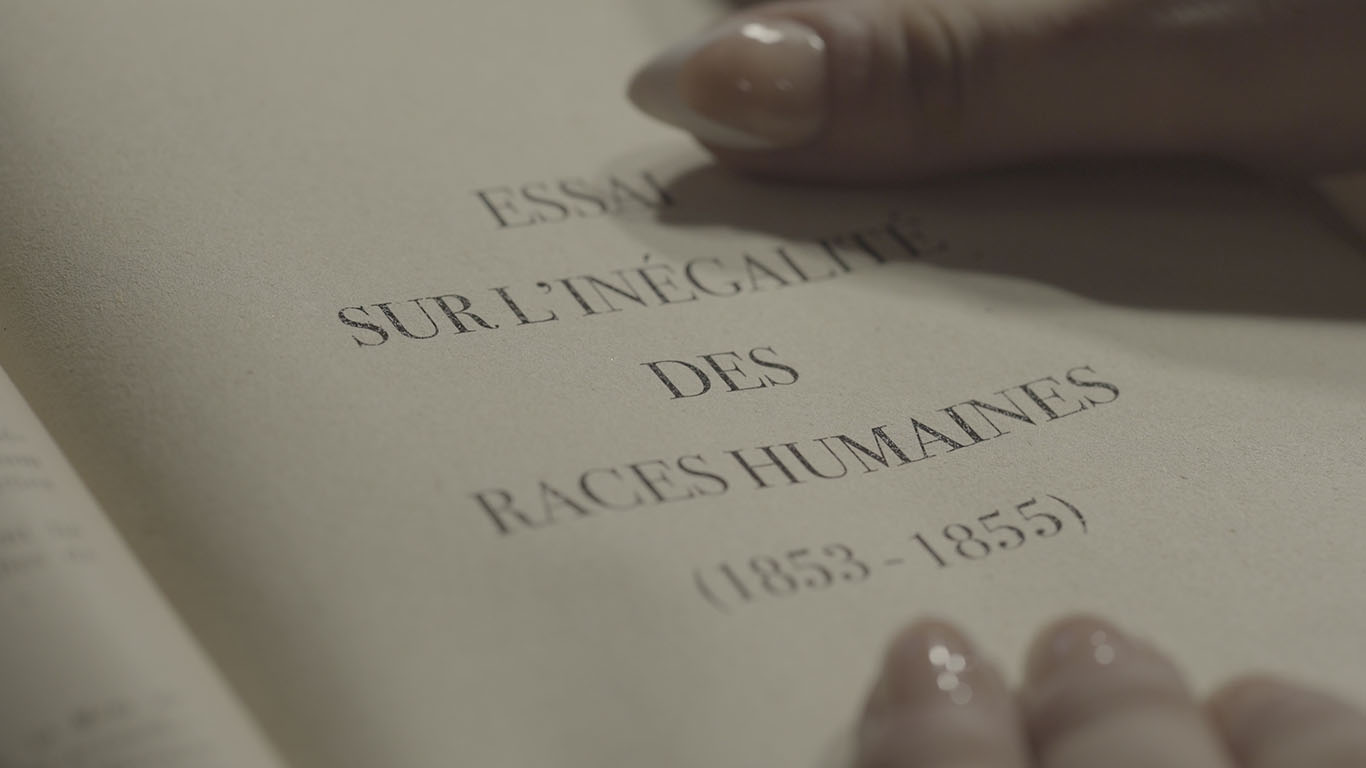

The video-cantata in the final room, The Emancipating Opera, emphasizes the aesthetic dimension of these relationships by raising the question of the colonial/decolonial dynamics inherent in aesthetic forms and concepts such as museums, poetry, beauty, and the idea of the public. Cutting between scenes in the Andes and the Chilean National Library in Santiago, the video adopts a musical template rooted in Italy while also foregrounding Amerindian stone carvings and peripheral libraries that house racist treatises. The trans singer and actress Daniela Vega merges the piece’s aesthetic concerns with the question of identity, chanting “What does it mean to be a woman?” Jarpa underscores the potentiality and necessity of an aesthetic reconfiguration of identities, with all the ambivalences that that entails. An enjoyable and curious aesthetic interest in the world around us becomes a counteroffensive against violent negativity. Points of aesthetically incited freedom and joint happiness extend across the boundaries among social groups.

Comparable strategies characterize many other contemporary works. John Akomfrah’s multichannel video installation The Elephant in the Room — Four Nocturnes (2019) meditatively reflects on the theme of migration — a constant in the artist’s oeuvre— in connection with environmental policy. The work invites us to experience in rethought terms the lived reality of African migrants, as well as the existential relations humanity, bears to materials and resources such as land and water. Mutually echoing with the gentle glances that we see migrants cast at each other and the contact that arises, the touching awareness of the sparse collection of objects they can carry along in a shopping bag and the perception of a struggling elephant population on the continent stand as images that can soften racist venom, puncture consumerist indifference, and melt nationalist rancor.

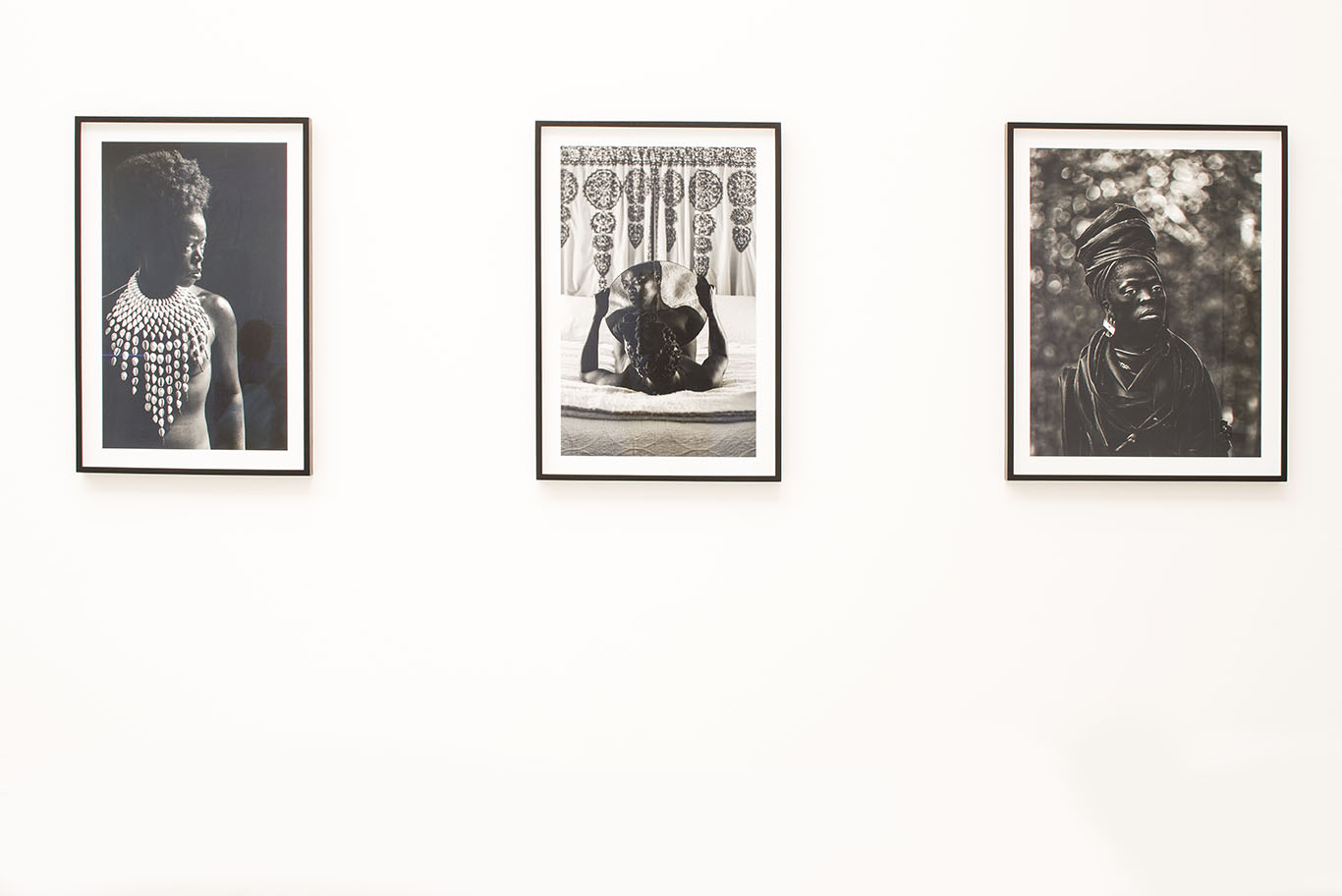

Performing blackness in ways that sidestep established visual scripts of address between photo and spectator, Zanele Muholi’s self-portraits outline possibilities for visual encounters on the part of audiences of many races with a black queer female body. The artist’s comportment in front of the camera is invariably self-composed. Their skin is darkened through make-up and editing. Meeting the viewer’s gaze with an astonishingly direct address, they present themselves adorned in accessories that mediate the representation. Many of these items are not readily legible. In Namhia I (2016), they wear headphones over two wooden sticks clasped to the sides of their head, sticks that also brace a construction reminiscent of a gas mask, film reels, a camera, machine parts, and a miner’s helmet. Directness of address goes together with a sense of complex imaginative mediation that solicits revised scenarios of encounter on the viewer’s part with black female subjects and the multitude of emotional tonalities and existential comportments they assume: questioning, skeptical, guarded, curious, weary, observant.

Filmmakers like Akomfrah and photographers like Muholi set into motion structures of relationality and address that are suggestive of enlarged, deepened notions of public freedom and flourishing. Objects, such as the shopping bags and the headgear, play a part in these dynamics. Our sense of the aesthetic tools for identity-making stretches.

Tarek Atoui’s 2018 sonic installation The Ground, on display in Venice’s Giardini during the 2019 Biennale, treats the visitor to a panoply of clanging, pinging, beeping, chiming, droning, and tinkling sounds created through invented instruments. Twigs and a string with a ball glide around white ceramic constructions. A stick runs over a warped clay disk, bumping into a metal object. New relations between objects and between spaces arise: a “Spin Collector” plays things instead of records. As Atoui suggests the sound of an old anthropological recording performs on a “Hybrid Violin,” intertwining the gallery space with the music’s historical setting and sound technologies while also rejecting received notions of an ethnographic assembly of human collectives in space.4 Reconfigured relations between sounds, people, things, and spaces point to alternative modalities of social and material existence. Our sense of our presence in public space shifts. We intuit unprecedented public freedoms and pleasures.

Finally, the performance opera Sun & Sea (Marina) by Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė in the Lithuanian Pavilion of the 2019 Biennale poses a joyful challenge for individualized notions of freedom and happiness. The opera turns a banal beach scene into an occasion for a fierce yet delightful and moving environmental critique and a commentary on corporeal fragility in the competitive capitalist workplace. The piece encounters the despicable ecological negligence and global exploitation that underlie the everyday agonies of consumer society not with a severe reprimand but with an easy, light recognition and a puncturing of the aesthetics of day-to-day life shaping white Western identity. The work extends an open-ended invitation to the audience to transform aesthetic relationships, while reminding us of the ongoing climate disaster. We face the urgent job of infusing the relations that intertwine living beings, places, and things with newly inspired energies and longings. Countering the ugly, destructive forces of terrorization that neoliberalism is fomenting, these pieces collectively call for a new ethical and political aesthetics of conviviality.