Tatiana De Pahlen: Gagosian Gallery, in Los Angeles, has just hosted an exhibition of your collaborative works. How did you start working together?

Bret Easton Ellis: I was, I guess, Alex’s favorite writer. We met when I moved back to Los Angeles, which was, more or less, ten years ago. Alex was just starting to do his own stuff.

Alex Israel: I was in graduate school. I was doing interviews for Purple Fashion Magazine and I asked Bret if I could interview him — Imperial Bedrooms had just come out. Then I asked him to be on my talk show, As It Lays. Eventually we became friends. A couple of years ago I began working with a writer, Michael Berk, to create the story and screenplay for my upcoming movie, SPF-18. I had a great experience throughout the process, and I began to think about other ways I could collaborate with a writer. The tradition of text-based art in Los Angeles has always been very attractive to me — and I wanted to find some way to engage it. Then the whole idea came together: I realized I should work with a writer to make text paintings; Bret is my favorite writer and also my friend, so I asked him.

TDP: How did you develop the texts?

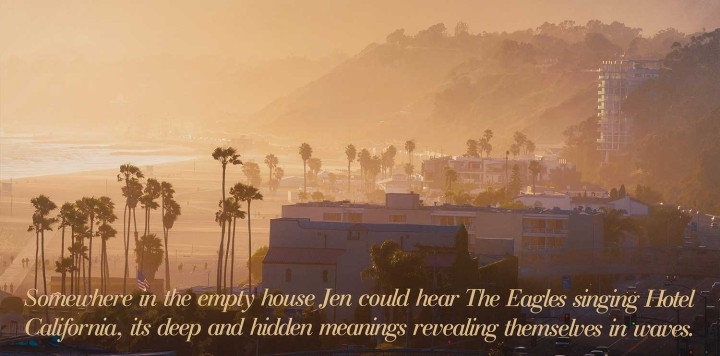

AI: It was clear from the beginning that the project would focus on Los Angeles — this was our starting point. So Bret began by writing a bunch of texts. Bret has a darker sensibility than I do; I’m a bit more optimistic about things. We chose the texts which were our favorites, the ones that met some place in the middle of our sensibilities, if that makes sense. After we had selected the texts, I took them home and turned them into paintings, first as mock-ups on the computer. I found an image, something that I felt was evocative, to pair with each text. Then I worked on the typefaces and the way the text was laid out over the image.

TDP: The images come from the Internet, right?

AI: Yes, they’re all stock photos that we purchased the rights to use.

TDP: Los Angeles is central to your respective practices; but, Alex, you approach the city in a more romantic way than Bret, I would say. You look at the old Hollywood. While for you, Bret, it’s more about the present moment — I mean, when you write it’s always a male man of your age.

AI: The city is the subject of my art because it’s what I know best — I was born and raised here, and I live here. I try to make art for the present moment. The work comes out of my everyday experience with the city. I get the sense that Bret, like me, is constantly resourcing material from the landscape, and of course, LA history is wrapped up in that.

TDP: But you express it very differently…

BEE: I would agree with that. Because I do think that, at the time I was growing up here, in the late ’70s and early ’80s, there was a glorious pessimism. It was kind of born out of the dissatisfaction of the ’70s, and was expressed in a lot of music that was about paranoia and conspiracy. The local punk-rock scene was really about that. That attitude folded into minimalism, which was also very popular at the time, if you look at the expressions of certain writers, artists, filmmakers. You could see it everywhere, from Raymond Chandler’s novels to the way Woody Allen shot Manhattan with Gordon Willis. Minimalism was really in the air. And Less than Zero was completely influenced by that. During 1982, ’83, ’84, Los Angeles changed into a more radiant, optimistic place. But Less than Zero was influenced by the negative energy of the city.

AI: I’m a child of the ’80s. And the 80s were a time of huge expansion in Los Angeles. Japanese money was flowing through the city and new buildings were rising up all over the place. Ronald Reagan was a Hollywood actor, and he became the president of the United States. In a way, Los Angeles had finally come to deliver on its promise. It was also the postmodern era: creative thought embraced the bringing together of disparate references. So if minimalism and pessimism were part of Bret’s spiritual and creative upbringing, for me, there was optimism and pastiche.

TDP: Do you think that in the collaboration on the text paintings these two generational mindsets have both emerged?

BEE: Well, I think they complemented each other. I also think that the way that we came together — in terms of my vision moving closer to Alex’s, Alex’s vision moving closer to mine, and us meeting in this middle point — really is what gives the paintings this kind of tension. I didn’t necessarily think this the first time we came together, because my vision was very, very dark while writing these texts. Then Alex brought them into the center stage where both my sensibility and his could coexist. That is really what the paintings are a reflection of — and in this sense, they are a true collaboration.

TDP: Yeah, I mean, Alex, you stayed very true to your art, and Bret, your literature is also very well represented. Bret, was this the first time you worked with an artist?

BEE: Yes.

TDP: And how does it feel to see your work as visual art?

BEE: It’s great.

TPD: How long did the whole process take?

BEE: We started talking about this in the summer of 2014 and asking each other: What is this going to be about? Where are these paintings going to live? There were many paintings that were discussed; we made mock ups that were discarded — the show is just a tiny percentage of what we did.

TDP: Are you going to use the discarded texts in a different format?

BEE: I don’t know. They are last sentences or first sentences of something larger. And they are about people who want something else, or want to be someone else, who have cultivated these double lives. That was something Alex really wanted to go for — this notion of wanting to be a different kind of star.

TDP: This sounds very L.A.

BEE: Yeah, but it’s interesting for me. Again, Alex has a youthful optimism. And he hasn’t been around long enough to know that in Los Angeles you only think that you’re coming here to reinvent yourself. While, what actually happens is that the city forces you to become who you really are. It forces you to deal with yourself, because it is an alienating place to live, it’s a lonely place to live — even if you’re not depressed, even if you’re not alone a lot. I’m alone a lot, and I have a boyfriend, and I have a lot of friends. Before I moved back here in 2006, I had never lived here as an adult. I would always visit and either stay with friends, or my mom, or in a hotel. I had never lived here on my own, in my own place. And I did it only in 2006. I will never forget that first week in my own condo.

TDP: Do you think that coming back made you see the city differently?

BEE: Definitely. The city is very different than it was in the ’80s — I mean, my God, in so many ways it’s better. Alex is completely right. There was no expansion in the ’70s. It was a dead city. But I loved that contradictory nature: I loved this beautiful place and this recession that was going on and it was so dramatic and jarring, like we’re at a beach and everyone’s depressed. That person went through five divorces and that person is going to die of a drug overdose, and the city is still stunningly beautiful.

But Alex is right. Today Los Angeles can make you very optimistic. I still don’t fully believe it, and I still know enough at this age that maybe Alex doesn’t yet. But today this is a city that during the first week I lived here drove me crazy, all I heard were crickets — it was so quiet. I looked out of my balcony, down on Doheny Drive, and there were no cars on it. And then I had no food in my refrigerator. So I got into my car — myself in my empty car — and drove down to the grocery store in the middle of the afternoon. There was no one out. I walked through the deserted supermarket and bought a sandwich. It was profoundly alienating. At first I found it exciting and thrilling, like: oh my God, this is like the desert. I never thought this is what Los Angeles was like. And I would talk to my friends, and a lot of them were just like, “Oh, you know, I don’t feel like going out”; or “You mean you want to meet for dinner? Really?” And then I went through about a year or two of dealing with readjusting myself to Los Angeles. And then I loved it.

I think Los Angeles is now a youthful city, a forward-looking city, a global city. It’s a great place to be creative. It’s different than in New York, for example. There’s more freedom here, a lot more freedom.

AI: There are just more options here now. For example, I saw you the other night at a fashion show…

TDP: That’s such an option. That’s the best option you can have here.

AI: You joke about it, but high fashion at that kind of international level hasn’t always been an option here in LA. This is somewhat new for us.

TDP: Indeed, a lot of people are coming to town that would have only come for cinema. I mean, one of the great emerging businesses is gaming. Do you have any interest in that?

AI: Not really, no. A friend of mine from high school became very successful in the gaming world. I don’t know much about it. We were just talking about how parking cars is like playing Tetris. I keep hearing people complain about the current LA boom from the point of view that traffic has gotten worse and worse, but I don’t mind the traffic.

BEE: I don’t hate it, but I don’t like to drive in it.

AI: I like the feeling of being in my car, listening to music, looking out the window or talking on the phone and just going from one place to the next. I find it meditative. When you’re in traffic you drive at a pace at which you can actually see and absorb the things you are driving by. I’ve used the shapes of windows and doorways that I’ve driven by to make works. And the paintings at Gagosian are very much like billboards. We talked about resourcing from the landscape — I think it’s something I do automatically when I’m driving, especially when I’m driving in traffic.

TDP: What about radio? I always wonder about what role radio plays in Los Angeles life.

AI: I’ve always listened to public radio, and now I have Sirius XM Radio too. It’s true: radio informs my life here. You grow up with the same DJ’s voice in your ear, year after year, and you feel like you know him or her — you feel like they are guiding you through the city. There’s one DJ in particular, Karen Sharp, she’s on KOST 103.5, and she does this evening show called “Love Songs on the Coast.” She has this mellifluous voice and she reads dedications like: “This one goes out to Bret from Tatiana. Bret, Tatiana wants you to know that you’re her favorite writer. She has been wanting to tell you this for a long time, but she feels it’s something that could only truly be expressed through this song…” Then they play Whitney Houston’s version of “I Will Always Love You.”

When I did a show at Le Consortium, in Dijon, I contacted Karen Sharp and I asked if she would do a pre-recorded radio show for me. She agreed, so I wrote out all of these dedications and she recorded them, in her very specific voice. I added in the music, and then I played the whole “radio show” on a loop in one of the exhibition’s galleries. It was funny. It created a sort of approximation of the experience of driving around Los Angeles, listening to music on the radio. This is basically the framework within which I do so much of my thinking, so I wanted to bring the viewer into that mindset.

TDP: Do you think it’s different when you work in Los Angeles as opposed to somewhere else?

AI: Well, the way I produce my art, how it actually gets made, is all very much a part of the work. Many of my works require, as fundamental to their existence, the Warner Brothers production crews to fabricate them. This process gives a Sky Backdrop painting, for example, the same exact quality as a movie backdrop. This is a quality that can’t be replicated anywhere else.

TDP: What about your upcoming film?

Alex: The film is called SPF 18. It’s a teen surf movie about four kids that end up together in Malibu in the summer between high school and college. They are trying to deal with teenager problems and they help each other. What ultimately happens is that creativity pushes them to find their voices. We shot it in Malibu last summer. It’s almost done.

TDP: How does it feel to direct a movie?

AI: As the director you’re responsible for creating a whole world, and everything in that world has to be just right. It opened me up to a whole other way of thinking, of being creative. It’s really the ultimate challenge, and I have a lot of respect for people that do it.

TDP: Tell us about working with other professional figures.

AI: There are a lot of people involved in the production of a movie. My work as an artist has always been made with the involvement of other people, so directing a movie was a somewhat natural — but also extreme — extension of what I’ve been doing. Because there are so many people involved in the project, what happens is that you end up learning different things from everyone. Ultimately, I ended up learning a ton.

BEE: You learn a lot about dealing with constraints. Like time: there is never enough time during the day. And dealing with actors and dealing with personalities. I love directing and I think it is something where you develop this totality of your vision.

AI: I did a little directing the other day, because Goldie Hawn agreed to narrate my movie and so we had to record her lines in a post-production sound studio. I had to explain to her where all of the things that the narrator said were coming from. I liked it.

BEE: Yeah, but you take responsibility for everything: the stuff that doesn’t work out, the stuff that looks great… I think the first time I ever directed anything I thought it was so great. But when I saw the assembled footage, aaahhh, it was brutal. It can be brutal the first time.

AI: I was sort of prepared for that — a director friend really prepared me. I had very low expectations for the first assembly cut, and then when I saw it I thought: Oh, okay, this isn’t a complete disaster yet. It just needs a ton of work.