After a thirteen-hour flight, I finally land in Tokyo — and instantly feel that unmistakable Japanese soul in the air. Even the way the airport staff handles the luggage is quiet, precise, almost choreographed. A different rhythm. A different world.

There’s only time for a quick coffee before rushing to the Shinkansen for Kyoto — but not without grabbing a travel bento, of course. As always: zero delays, zero stress. I sink into my seat, exhale, and let the high-speed calm take over. The city dissolves into the horizon, Mount Fuji rises like a serene apparition, and then soft waves of countryside unfold in peaceful succession.

At Kyoto Station, the first real punch of jet lag hits, but it’s definitely not bedtime yet. A gentle wander through Nishiki Market keeps me awake: colors overflowing, aromas swirling, vendors calling out softly, food everywhere. Dinner is spectacular, naturally. Then, finally, sleep.

Morning begins at Ryosoku-in Temple with a Zen meditation led by monk and zen master Toryo Ito. A moment of stillness so grounding it’s like a reset button. Breathe in. Breathe out. The temple is also hosting a beautifully intimate duo exhibition by Los Angeles–based couple Jonas Wood and Shio Kusaka, presented by David Kordansky Gallery. Wood’s paintings and Kusaka’s sculptures converse quietly across the temple space, creating an energy that feels both deeply personal and perfectly attuned to the surroundings.

Then it’s time for ACK, Art Collaboration Kyoto, one of Japan’s most forward-thinking art fairs. The fair unfolds in two main currents: “Gallery Collaborations,” where Japan-based galleries partner with international peers in shared booths; and “Kyoto Meetings,” highlighting presentations that hold meaningful ties to the city, including contributions from celebrated international galleries like Perrotin, Sadie Coles HQ, and Kurimanzutto, among others.

And at the center of this ecosystem stands Yukako Yamashita, ACK’s Fair Director, whose vision is unmistakable throughout the fair. She champions ACK not as a typical marketplace but as a bridge — a place where Kyoto’s centuries-old artistic heritage meets the pulse of global contemporary art. For Yamashita, collaboration is not merely a theme: it is the mechanism through which the fair operates. Her belief that Kyoto should serve as an active partner — not a backdrop — shapes the fair’s rhythm, hospitality, and curatorial intelligence. Under her guidance, ACK becomes a living site of exchange, where every pairing of galleries and every presentation feels intentional, relational, and deeply rooted in place. This edition also marks Yamashita’s final year leading ACK — an emotional and symbolic closing chapter for a director who has profoundly shaped the fair’s identity since its inception.

ACK’s public program, curated by Martin Germann and Kokoro Kimura, draws inspiration from a major historic milestone: the Kyoto Protocol, which entered into force twenty years ago. Adopted in 1997 at ICC Kyoto — Sachio Otani’s seminal architectural achievement, winner of Japan’s first national design competition in 1963 — the Protocol reawakens here as a living memory. Art activates the building, not only as a physical container for works but as a historical residue etched into the very structure. Right at the entrance, Berlin-based artist Phung-Tien Phan greets you (or perhaps disorients you) with an absurd assemblage — a witty, deadpan reflection on the constructed theater of contemporary identity, online and offline. Inside, Stella Zhong’s Yolk Velocities (2020) stretches time itself, echoing the slow, suspended hours of the pandemic. Installed as a site-responsive work within ICC Kyoto’s iconic brutalist architecture, it captures Zhong’s playful, meta-reflexive approach.

Nearby, Taro Nasu hosts Gladstone, presenting Precious Okoyomon’s new plus companions, hung from the ceiling and welcoming the public. 18, Murata (Tokyo) pairs with Matthew Brown (Los Angeles), featuring Omari Douglin’s paintings inspired by past travels through Japan; Crèvecooeur shows two works by Louise Sartor. Tokyo-based gallery 4649 exhibits vibrant works by London-based Motoko Ishibashi — a technicolor dive into online imagery and contemporary culture — while also hosting Chicago’s Good Weather, showing Nancy Lupo’s subtle transformations of everyday objects. And Misako & Rosen brings the thread full circle with works by Phung-Tien Phan, reconnecting to the public program.

A quick stop for standing soba — fast, hot, perfect — and then off to the Kyoto opening of LA-based gallery Nonaka Hill, presenting a beautiful new exhibition by Adam Alessi. In recent years, Alessi has spent long stretches in Japan, creating much of this work in an improvised attic studio deep in remote Iga. This isolation offers a rare creative stillness, far from the bustle of New York and Los Angeles. The show brings together new paintings, drawings, and sculptures shaped by this introspective rhythm — a body of work born from quiet, concentrated solitude.

The night ends at Fortune Garden with a one-night performance by queer Japanese artist Ei Arakawa-Nash, based in Los Angeles and set to represent Japan at the 2026 Venice Biennale. Their upcoming project is profoundly intimate and socially charged: drawing from their experience as a queer parent of newborn twins, the artist explores how family, care, identity, nationalism, and patriarchy intersect and collide.

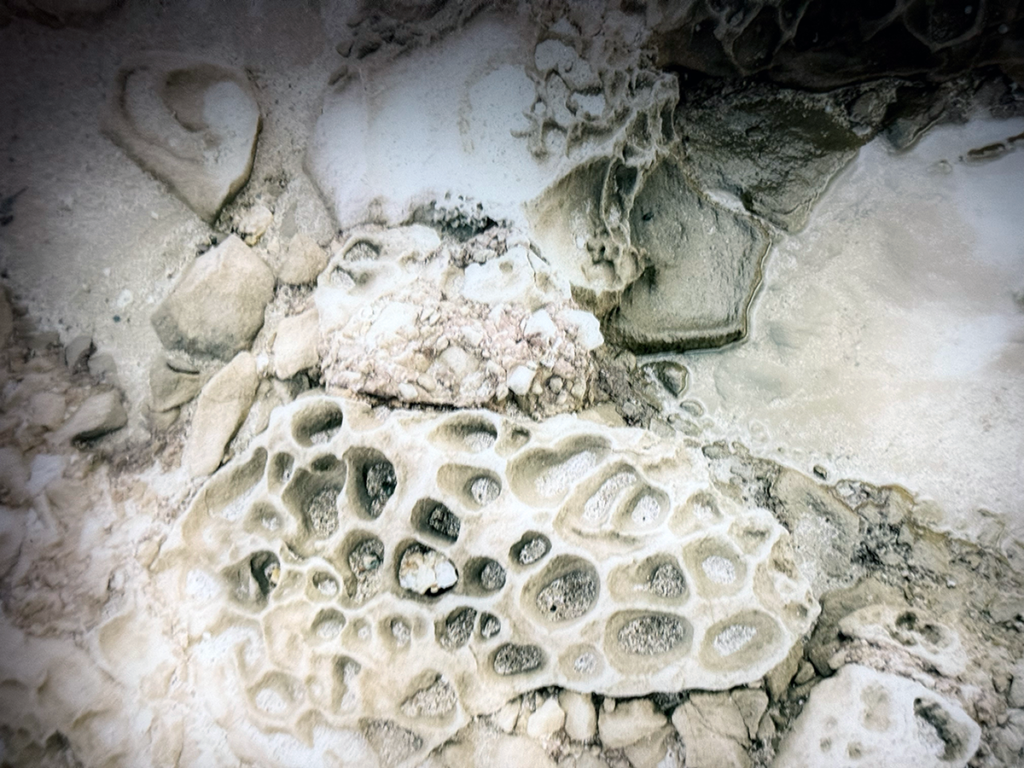

The next morning, I head to Kanazawa in Ishikawa Prefecture — a region still healing from the devastating Noto Peninsula earthquake nearly a year ago. That disaster took 236 and left deep scars across homes, infrastructure, and the local community. In this resilient atmosphere, the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art — renowned internationally for its bold architecture and visionary exhibitions — has invited the Tokyo-based collective SIDE CORE to develop a special project rooted in the disaster’s aftermath.

SIDE CORE, influenced by the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, approaches street culture not as a purely urban aesthetic but as a connective tissue — “the street” as a bridge between places, values, and communities. Their exhibition links geographies and personal experiences through roads, movement, and exchange. Rather than simply showing works, the project constructs temporary “other streets” inside the museum, inviting visitors to feel movement, encounter new values, and inhabit alternative rhythms. Skateboarding, graffiti, and music appear not as spectacle but as everyday gestures of life, woven into the museum’s architecture. The institution becomes a crossroads, where diverse ideas and expressions converge, suggesting new ways art can exist within formal spaces. Before catching the Shinkansen back to Tokyo, I have just enough time to pick up pottery from local Noto artisans — a small but meaningful way to support the region’s ongoing recovery.

Tokyo greets me once again with its signature silent chaos at the station. One last check-in, one last perfect dinner — and the journey comes full circle.