Eight noses jut from the façade of the Kestner Gesellschaft in Ian Waelder’s exhibition “thereafter.” In Self-Portrait as My Father’s Nose (2025), these monumental forms — cast from papier-mâché and coated with fat, seeds, and agar-agar — extend outward, gradually eroded by birds and weather. The work nods to Dieter Roth’s P.O.TH.A.A.VFB (Portrait of the Artist as a Vogelfutterbüste) (1969), while its form derives from the “Waelder nose,” which the artist sculpted together with his father — one of several collaborations in the show. Born in Madrid, Waelder carries a German-Jewish heritage through his Chilean father, and is the first of his lineage to return to Germany since his grandfather fled in 1939. This autobiographical return grounds a visual language attuned to memory and the unstable archive — history conceived as a fragile constellation of personal and collective traces.

My first reaction to the noses was hesitation. The exaggerated Jewish nose is so deeply sedimented in the visual history of caricature that to reproduce it — even as homage — feels semiotically overdetermined. Yet this discomfort is precisely what animates the work. Within Germany’s postwar Erinnerungskultur, Jewishness is largely framed through an a-corporeal, religious lens — recognized primarily as a Religionsgemeinschaft, or religious community. This institutional categorization reflects both the way postwar Jewish organizations in Germany have tended to self-identify — as religious rather than ethnic bodies — and the Federal Republic’s desire to avoid reproducing the racialized definitions of Jewishness codified under the Nuremberg Laws. Yet this framework has also shaped public and institutional rhetoric around remembrance and responsibility, centering “faith” as the dominant register and, in the process, abstracting the more embodied cultural, social, and genealogical dimensions of Jewish identity — dimensions that are as integral to the community’s own individual and collective practices of remembering as they were to the logic of their persecution. Interpreted through this lens, putting eight huge Jewish noses on the facade of a German institution is a rather ballsy way of making this tension visible. Made from materials designed to rot, their slow decomposition mirrors the abstraction of corporeality from institutional memory. In this sense, the work punctures cultural amnesia, reasserting more explicitly embodied dimensions of Jewish identity.

This motif, and its reading, form only one register of Waelder’s practice — which should not be reduced to it — which orbits what might be called a minor archive — composed of partial gestures, everyday residues, and inherited traces. His visual language, spanning sculpture, sound, installation, and found media, carries an anti-monumental ethos that privileges uncertainty over order and affect over declaration, situated within a broader aesthetic lineage invested in dialectical, unresolved continuities that cut across linear historiography: a mode in which the past persists as a “haunting” force in the present.

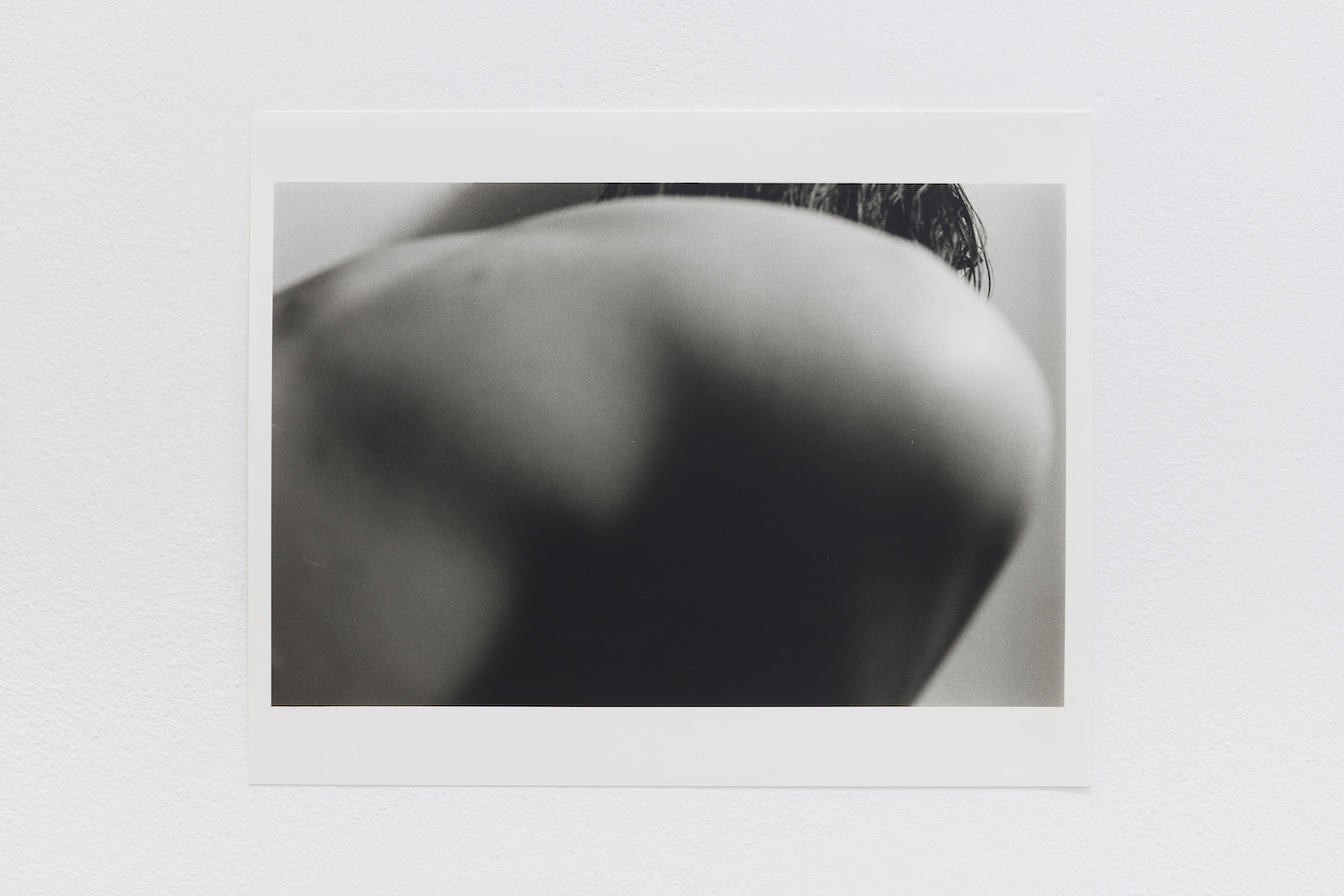

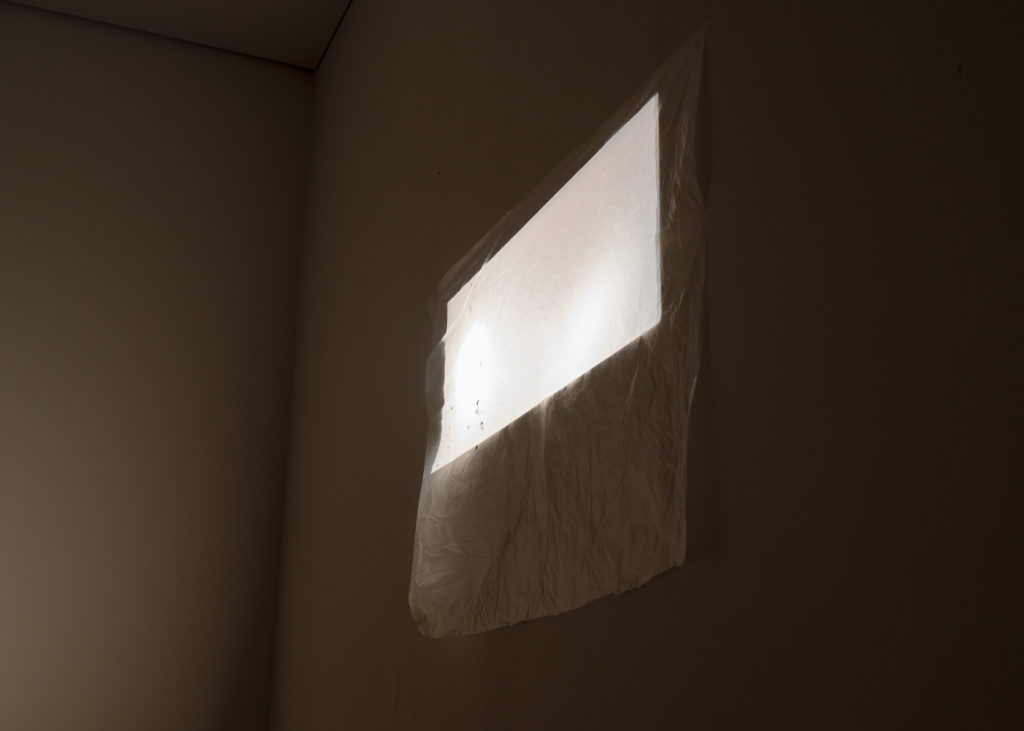

Inside, visitors step into a labyrinth of corrugated cardboard and translucent plastic. The air smells faintly of glue and paper; light filters through veiled off shafts; the softened floor dulls every step. This rather Kafkaesque installation is choreographed through sensation as much as sight: everything yields slightly, as if memory itself were porous. Works appear almost incidentally within this architecture. Sprain (38) (2023) — an antique wooden last fused with a porcelain nose — reads as a surreal portrait from head to toe. The shoe, a recurring motif in Waelder’s practice and personal obsession as a skateboarder, becomes a vessel of motion and memory, imprinted with bodily trace. Nearby, a hidden sculpture — another realistic nose modelled on his father’s tucked into a cardboard box — functions as a near-invisible echo of the outdoor piece, reinforcing the show’s logic of concealment and revelation. Along a dim corridor, Bystander (Ankle/Thread/Right) (2025) presents casts of shoe interiors threaded with laces: hollow forms that make absence tactile, memory manifest as negative space.

Sound structures the show’s psychic architecture. In As Far As I Can Recall (Dad on Piano) (2025), Waelder’s father haltingly attempts to play a melody once composed by his own father. The hesitant tune folds into the slow dripping of All of My Shoes (Tempo) (2025), where water trickles from a pipe onto a beeswax-coated cardboard insole, amplified through a microphone. These sonic works stage generational memory as glitchy, unstable transmission — heritage as imperfect repetition.

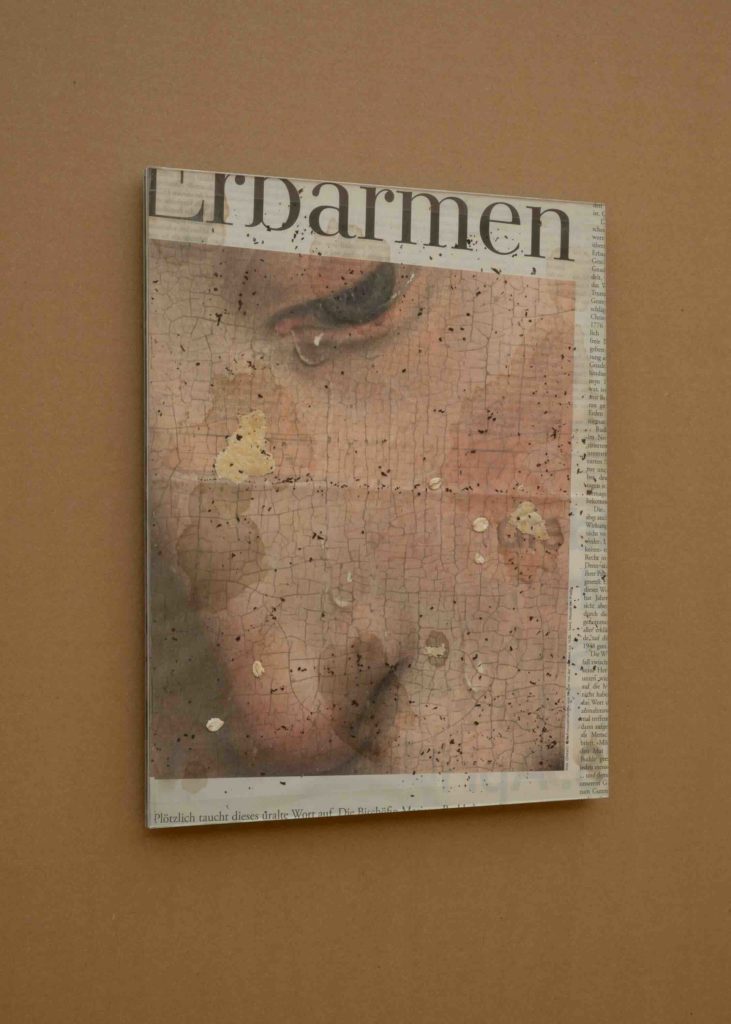

In the main gallery, Mercy (Leak) (2025) isolates a page of the Süddeutsche Zeitung, its headline reading “Erbarmen” (Mercy), stained with tea, butter, and oats — the remnants of the artist’s breakfast. The work grew from Waelder’s daily ritual of collecting newspapers after moving to Germany to work on his language-skills, acting therefore as another kind of corporeal, “stained” record. Suspended above, a constellation of other newspaper clippings filters the light, interspersed with black-and-white film stills of anonymous children playing hide and seek. The installation generates a diffuse atmosphere of pseudo-nostalgia that, through its investment in the minor archive, spectral imagery, and deliberate nonspecificity, aligns with the exhibition’s broader methodology. Yet this affective register remains somewhat disembodied; I found myself wishing for a more situated, corporeal link — an elliptical thread binding these fragments more directly to the exhibition’s other works.

Upstairs, along the café wall, Background Vehicle (Running Scene) (2025) reworks three plotter-printed canvases that layer the same film stills of playing children, this time isolating a single boy mid-run. In the original footage, an Opel Olympia appears in the background — an image that became central to Waelder’s research, given that the same model was once owned by his grandfather and sold in 1939 to finance his escape from Germany. Across these canvases, however, the car has been deliberately cropped out. Its erasure becomes the work’s ghostly anchor, transforming absence and the “negative body” once again into subject. Each canvas is coated with raw linen, glue, oil, and filler; from the side, only stains and shadows are perceptible, while from the front, the child’s figure re-emerges. The oscillation between opacity and legibility mirrors memory’s instability — and, by extension, Waelder’s self-reflexive method, where each repetition of a motif subtracts a little more information, allowing history to surface as “after-images”[1] — psychic and material traces through which the past continues to register affectively in the present.

[1] Griselda Pollock, After-Image: Trauma and the Aesthetic of the Contemporary (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013)

thereafter reconceives the archive as an unstable, affective terrain in which history survives not through representation but through residue. Waelder’s practice, while skeptical toward the authority of the archive, remains tender toward its fragments — the fragile materials and their ghosts through which the past endures in negative space, in the interruptions and gaps in between. The exhibition’s strength lies in this balance between abstraction and intimacy, the conceptual and the corporeal — and being, at times, “on the nose” in the right way.