The current exhibition at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels presents a selection of Charline von Heyl’s latest paintings and prints. Her work enacts fractured gestures, and a push-and-pull between language, layering, opacity, and intuition.Installed in the gallery’s pristine, high-ceilinged rooms, they appear at home. At the entrance I’m told there is no predetermined order across the three gallery floors – the impression is that the works move or exist in a choreography of their own.

To writers, words are material, and grammar and punctuation are some of their tools. In her workbook Steering the Craft (1998), Ursula K. Le Guin notes, “If you aren’t interested in punctuation, or are afraid of it, you’re missing out on some of the most beautiful, elegant tools a writer has to work with.”[1] I imagine a similar toolkit existing for painters: lines, shapes, planes, patterns, stencils, colors transmitted in pigments on canvas or paper. Von Heyl’s visual vocabulary feels, at first glance, like abstraction made articulate – but to stop there would be to miss the interplay between painterly matter and linguistic echo. For von Heyl, words and images are not neatly divided territories. In interviews, and in the titles she gives her works, a guiding, poetic sensibility toward discourse is palpable. The comparison seems fruitful: if a writer shapes words for an imagined reader, von Heyl’s paintings propose a paradox. They both solicit and refuse the viewer’s interpretive gaze, pulling us into a spiral of meaning only to push us back toward sensation. Like a poet choosing a line break, von Heyl bends and repels the charge of words, crafting something elliptical, and ultimately holding out against fixed exegesis.

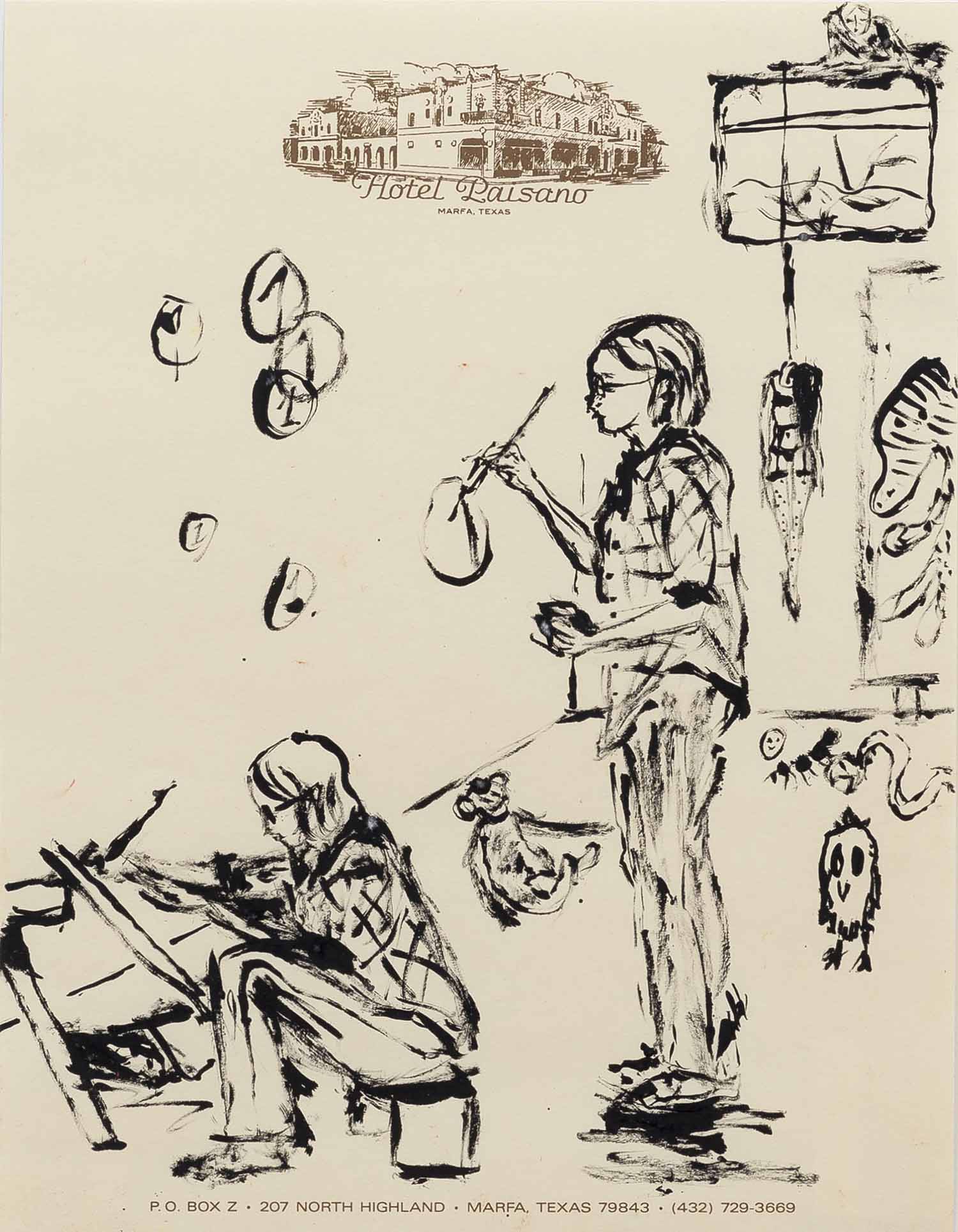

Describing herself as her own first audience, von Heyl explains that she needs to be surprised by the painting’s automatism. The picture leads the painter somewhere it wants to go. There is no abstract, only painting. There is no understanding, only thoughts. The works unfold despite themselves; painting begets painting. They spiral inward, curling not just toward the viewer’s stomach but into the stomach of the canvas, past any predetermined vocabulary. They ask us to attend to fleeting impressions rather than the solidity of explanation. In her 1976 essay Why I Write, Joan Didion describes her own process as navigating “images that shimmer around the edges”[2] projected on the mind’s eye — images that are unstable, difficult to pin down, and often lost in the act of transcription to the page.

The picture tells you how to arrange the words and the arrangement of the words tells you, or tells me, what’s going on in the picture.

Nota bene*

It tells you.

You don’t tell it[3]

The works in the exhibition can be approached in a comparable way: as attempts to follow mental images into form, assembling fragments that do not necessarily resolve but leave traces. This desire for surprise, however, might be overstated. Since any vocabulary is limited, the work still falls within a set of outcomes that doesn’t per sé push the envelope of the oeuvre.

In von Heyl’s recent canvases, matter has weight but not density. Unlike the recent vogue for materialist maximalism – or its mirror section, material negation – von Heyl displays instead a painterly Spielerei. Pigments, strokes, shapes, planes: though one hesitates to call them characters, as viewers (and as readers, or worse, as writers) we can hardly help narrativizing them, desperate to construct twisted, non-linear stories, scenes, plots, or accounts of gestures. The paintings embody a desire to move beyond language while still provoking it. They aim not to steer our interpretation but to activate a visceral, “gut reaction of the mind.” Is this instinct? Is it pathos? Or is it something more tenuous like the staging of an idea-image that never fully resolves?

Among the strongest works at Xavier Hufkens are Kunterbuntergang (2025), Uccellacci e uccellini (2025), and Space is a Doubt (2024). What ties them together is not style — something von Heyl spent decades evading — but a breathing rhythm, a logic of juxtaposition. Kunterbuntergang stands out as one of the strangest, in the best sense: a cartoonish choreography of bowling pins, equine legs, and a giant sunflower-sunset collapsing into one another.

By contrast, Uccellacci e uccellini feels more direct. Its cinematic references are legible: birds and stenciled letters intrude into the picture, pulling text and image into dialogue. The title cites Pasolini’s 1966 film, in which a talking crow both guides and misguides its human companions. The allusion carries a fable-like, magical-realist timbre that suits von Heyl, who often toys with animal figures and the murmur of nonhuman speech. The press release folds in Rilke, making a wink between the painting The Open (2025) and Rilke’s writing – With all eyes the creature sees into the open. In Speak in Spores (2025), where discourse mutates into vegetal or fungal languages, echoing contemporary fascinations with the organic and the posthuman. Whether the imagery upholds these references is uncertain, but their resonance, even if only pro forma, lingers.

The paintings teeter between hints of figuration and pure graphic shape, between cryptic titles and ambiguous imagery. Their layering is neither deep enough to immerse the viewer entirely, nor flat enough to be read as pure graphics or fascia. They unravel in tenderness, spiraling outward while remaining anchored in a distinctly 20th-century register — Abstract Expressionism, Pollock, Cubism, Klee. For someone born around the cusp of the millenium, there is a slight dissonance on encountering this work: Are they relics in and of themselves, or is their maker nudging and winking? It feels both out of time and utterly at home in this particular context. The oeuvre straddles its references like a transatlantic accent, never quite settled by categorization, circling instead in ineffable gestures.

[1] Ursula K. Le Guin, Steering the Craft: A Twenty-First-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story (Silver Press, 2024).

[2] Joan Didion, “Why I Write,” in F. R. David, Inverted Commas, ed. Will Holder and Riet Wijnen (Glasgow: uh books, 2017), 6.

[3] Ibid, 7.