Rome, Paris, Manchester, Riyadh: four cities trace the trajectory of a curator who has made transdisciplinarity and innovation his signature. Valentino Catricalà represents a new generation of cultural practitioners, capable of crossing both geographical and conceptual boundaries — building bridges between tradition and the future, between academic research and radical experimentation.

From the Italian capital — where he learned that “past and present coexist in a balanced chaos” — to tech laboratories in Paris, to gallery spaces in Manchester, and the vast cultural development sites of Saudi Arabia, Catricalà has developed a curatorial approach that challenges the conventions of the contemporary art system. His journey is not only professional, but also geographic and cultural: a path that has led him to rethink the role of the curator in the digital age and in rapidly evolving cultural contexts.

A pioneer in bridging art and technology, Catricalà has long anticipated issues that are now central to the contemporary art discourse: artificial intelligence, sustainability, and new models of cultural production and experience. More importantly, he has demonstrated how curating can serve as a tool for social transformation — capable of attracting new audiences and generating innovative forms of funding and partnership.

Today, from Saudi Arabia — where he is contributing to one of the most ambitious cultural development projects of the 21st century — Catricalà offers a unique perspective on the shifting geopolitical balances of the contemporary art world. At a time when Europe struggles to reinvent itself and the Middle East emerges as a new global cultural hub, his experience becomes emblematic of the challenges and opportunities facing a rapidly evolving art system.

A dialogue across continents and cultures, in search of new forms of curating for the future.

Cristiano Seganfreddo: Let’s start from your beginnings, how did you become a curator?

Valentino Catricalà: I started in Rome, a particular city, caught between its “I have been” and its “not yet,” a city constantly in potential, but often, precisely because of this, with great difficulties in actualizing and making its potential concrete. But Rome is also an inspirational city, a city that, while struggling to establish itself in the contemporary art world, can be of great creative inspiration. History lives accumulated in Rome, past and present coexist in a balanced chaos: transdisciplinarity, the ability to connect different fields and different points in history – this is its teaching.

My PhD, developed between Rome and Dundee, in Scotland, with research stays at ZKM in Karlsruhe and the Tate in London, gave me a great theoretical foundation that I still carry with me. I cannot conceive of curating without a strong theoretical base, which doesn’t mean academic, but means having a perspective, research, a vision. Not just taking the coolest artists of the moment and exhibiting them, but bringing one’s own vision, an approach that is also research-based.

And so I started by curating exhibitions and with the first major project, the Media Art Festival held at MAXXI in Rome, promoted by the Fondazione Mondo Digitale, which immediately established itself as an interdisciplinary project that managed to bring international artists, new formats, such as artist residencies within technology sector companies like Epson and Google, and new sponsors, from BNL to Samsung to the Ministry of Culture. I have always tried to propose innovative projects, to find new curatorial methods and sponsorships, often at the limits of contemporary art, like the collaboration with Rome’s Maker Faire, Europe’s largest creativity and innovation fair. Or like the collaboration with Sony Lab in Paris. And then I left, I went to Manchester.

CS: How did you concretely manage to integrate SODA’s educational dimension with MODAL’s curatorial programming in Manchester? Can you tell us about a specific example of a project or exhibition where this integrated vision between education, production and exhibition was realized in a particularly effective way?

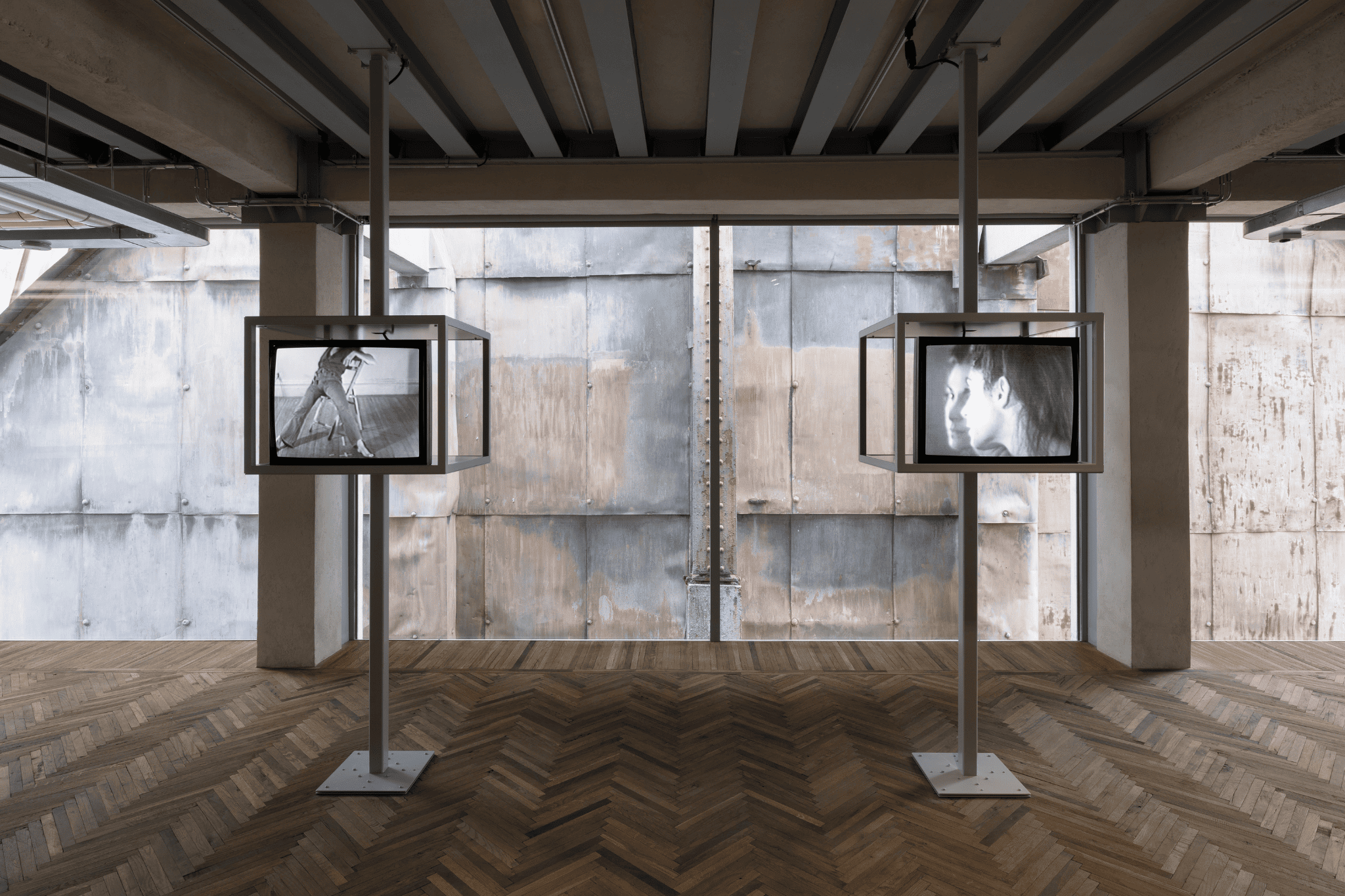

VC: In Manchester I was hired as curator and then artistic director of this new art center, a new center for the arts linked to technology and new languages. A 35 million pound project that went to Manchester Metropolitan University for a new School (SODA-School of Digital Art) and an art center (MODAL). We had exhibition spaces where we structured a very clear narrative that united the research of young artists with the pioneers. Each year we decided on a theme and developed exhibitions within this theme. We did great and beautiful projects and revalued pioneers.

Here too I immediately sought to find an innovative way of conceiving curation, not separating the school from the exhibition part. The school was full of very high-level technological laboratories, so when I saw the project for the first time I immediately thought that we couldn’t limit ourselves to just the exhibition part, but it could be a new vision that united exhibitions with production and education. And so we did, thanks also to collaboration with institutions such as the Prada Foundation, Serpentine Gallery, FACT Liverpool, and in Manchester with the AND festival and the Manchester International Festival. It was immediately a success, and so in Saudi Arabia I think they noticed me as a “launcher of new projects.”

CS: Tell us about your arrival in Saudi Arabia, what brought you to Riyadh and how has your role evolved over time? What impression did you have of the Saudi cultural scene at first approach? And what has changed since then?

VC: The arrival in Saudi Arabia was completely unexpected and completely new: from Manchester to Riyadh, from rain to sun… from so much rain to so much sun!

I think launching a new institution is a privilege today, and I’ve had the opportunity to do it both in Manchester and now. Saudi Arabia is a territory in constant evolution, full of enormous projects to build. The real stimulus comes from the fact that one feels part of a world under construction, unlike Europe where much is already built – a new sensation for those of my generation, but truly stimulating.

When I arrived in Saudi Arabia, however, I immediately realized that it was a country I didn’t know and had never made an effort to know. I realized, in short, that it was a country with a deep culture, completely different from ours, and that I had to know if I wanted to work there. Saudi Arabia is a unique place for its culture and history, it’s not comparable to Qatar or the UAE, places where internationals are the majority percentage. In Saudi, all the things we do are for Saudis first and then for the rest of the world. And so I understood that understanding the incredible cultural change that is happening could not ignore understanding its history and culture.

Today Saudi Arabia is an incredibly vital territory, with a young artistic scene in constant evolution. A territory that is trying to unite tradition with innovation, to create a bridge between its own history and culture with Western culture. You can see it from the emergence of the artistic scene, a scene that is incorporating the languages of contemporary art, but is declining them through its own cultural and historical mechanisms. This is why they are very interesting for us, something we have never seen before.

CS: You are recognized as one of the leading experts in the relationship between art, technology and innovation. How do you see the development of this sector?

VC: I studied the relationship between art and technology for many years, initially feeling part of sectors such as media art, new media art, etc. But I think many things have changed today. Today it’s increasingly difficult to delimit specific areas related to the relationships between art and technology. If we look at the work of artists born in the eighties and nineties, we realize that there is no longer a great distinction between where a medium begins and ends. The way new generations engage with media is fluid and transversal, it can incorporate technological and non-technological media, innovation and tradition. Therefore, it’s no longer the medium that delimits artistic fields.

Despite this, I believe that precisely today we need the experiences and research developed from the 1950s to today in areas that have been at the margins of contemporary art, such as media art, video art, etc. There are pioneers who have worked with artificial intelligence, genetics, robotics, and much more, pioneers marginalized by the art world but who today can represent a new way of re-reading art history and our contemporary world. And a new perspective can come precisely from the work of artists operating in new contexts, such as the MENA region, which also includes Saudi Arabia, like the exhibition at Diriyah Art Future in Riyadh.

CS: How has your curatorial approach transformed in the different countries where you have lived, having an international approach beyond Europe?

VC: This is a good question. Actually my curatorial practice has changed a lot as my relationship with abroad grew. Above all, from the beginning, it has been a practice based on a particular path, already my PhD was halfway between contemporary art, cinema and media studies. This approach marked an attitude that, I believe, managed to bring new areas into the art world, I think for example of the relationship with the innovation world (I also published a book about it titled “The Artist as Inventor,” with the idea that the artist who uses technology can also re-read the innovation world), collaborations with Sony Lab in Paris, Epson, Microsoft and Google, curatorial projects with Maker Faire. Or the more recent collaboration with entertainment sector companies like Lux, with which we brought an exhibition dedicated to the relationships between art and inflatables to the Grand Palais with incredible public success.

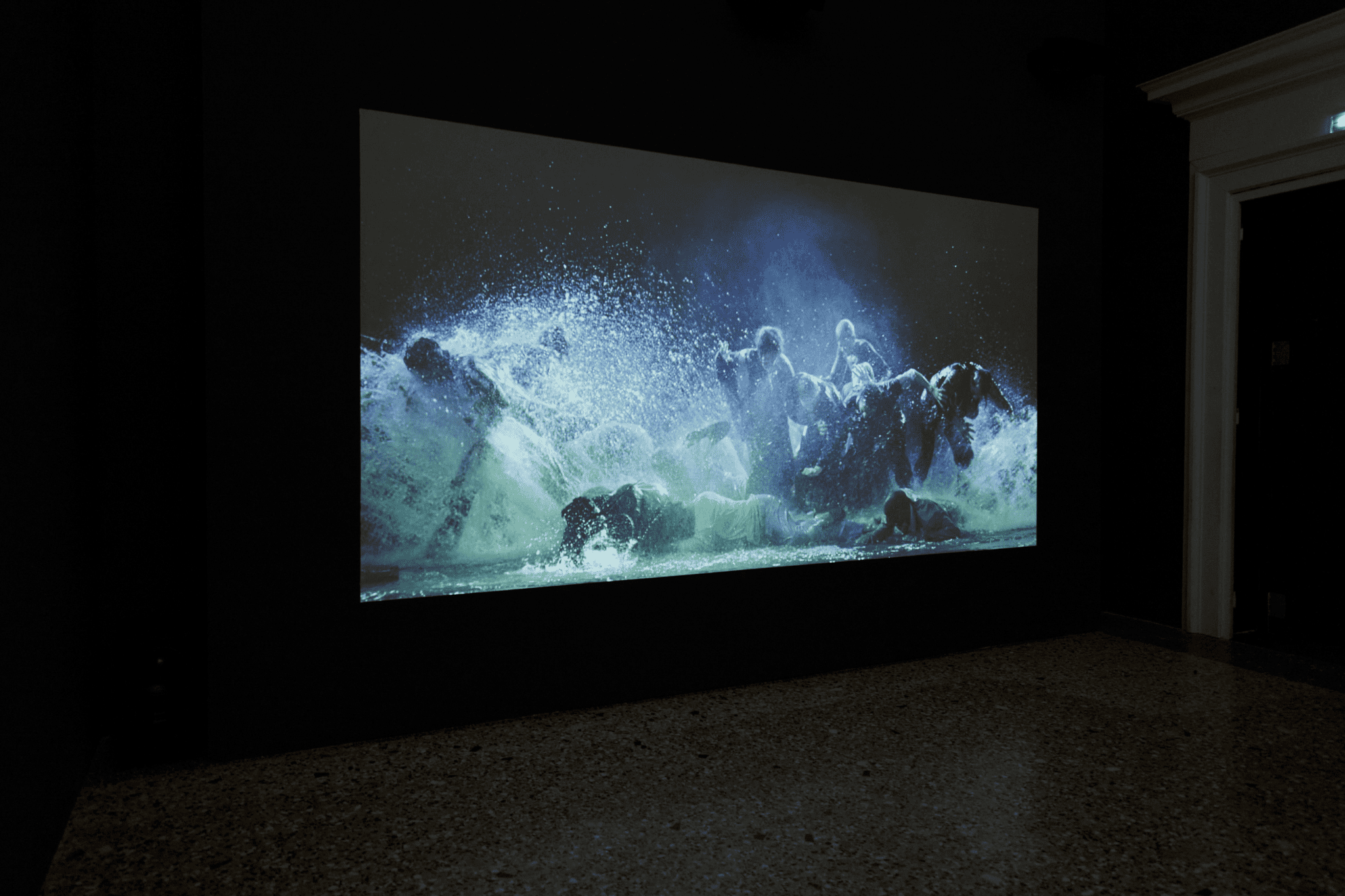

All this in parallel to more classic curatorial and research practices. I think of the Bill Viola exhibition at Palazzo Reale or those developed in Manchester. In Italy it was seen as a bit too much at the limits and I was often criticized, in Manchester instead they encouraged me to go in this direction, with high-prestige partnerships, like the beautiful collaboration with the Prada Foundation for the exhibition on Dara Birnbaum.

And this to experiment with new projects, find new funding and attract new audiences. I believe a new attitude is fundamental for the art world, a world that needs renewal, given budget cuts and loss of audience. Often we lock ourselves behind our research without looking at society that is changing rapidly also from a technological point of view. And all this is an incredible field of experimentation in Saudi Arabia, a country that is facing unprecedented cultural change, and the creation of a new world.

CS: On this subject, there is much talk of “new cultural models” in the Middle East, especially in Saudi Arabia. What are, in your opinion, the elements that make this historical moment so unique?

VC: The Middle East is a place in great expansion and change for more than twenty years now. The UAE started, Dubai was the first major city to establish itself internationally as a financial and economic power, followed by Abu Dhabi regarding culture. And certainly Doha in Qatar followed, representative of a change not isolated to a single country but to a real will of affirmation of the Gulf countries at an international level.

Today, the new arrival is Saudi Arabia, which is establishing itself at an incredible speed with unprecedented force, but, unlike the other two countries, in a completely new way. Saudi Arabia, in fact, is the one with the largest number of local population, which makes the cultural presence very strong. We think that the UAE has 88.5% expatriates, while in Qatar locals are only 15%. Almost all cultural projects in Saudi Arabia are for Saudis first and then for internationals, and they don’t link to international brands, like the Louvre or Guggenheim, but have local styles and methods. This is very interesting and I think it can really make a difference in affirming a new cultural model, made of a union between Western formats and local traditions. It’s not an easy thing obviously, but it’s the new challenge.

CS: Saudi Arabia seems to focus on an idea of culture deeply projected toward the future, with a strong investment in technology and experimentation. Is this really the case? What is, today, the role of contemporary art in such a broad transformation process, involving economy, society, identity? What is the relationship between contemporary art and new generations in Saudi Arabia? Is there a demand for new, young, experimental culture?

VC: Absolutely yes. Saudi Arabia is a particularly digitized place, it’s ranked fourth worldwide for digitization! Technology, therefore, dominates in a population that is 70% under 30. This is one of the great differences with Europe, young people are the majority, and the changes taking place derive from this vital territory that absorbs innovations very quickly. But let’s not forget that Saudi Arabia is also a territory that holds its cultural traditions very dear, which are very strong. Tradition and innovation are two fundamental terms. This also has repercussions on contemporary art.

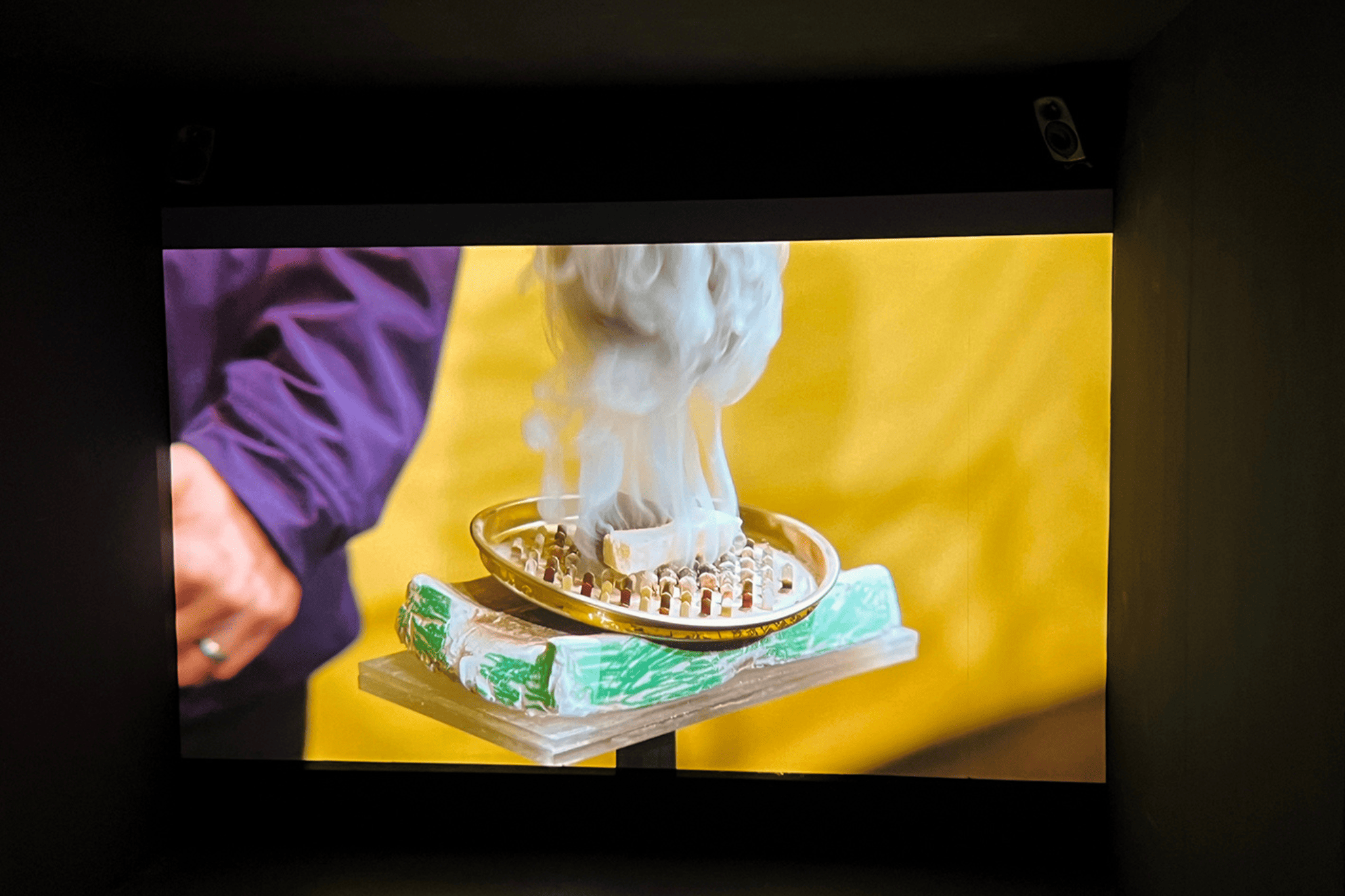

The artistic scene is growing and many artists use technologies and reflect on the great cultural and technological changes of our present. From more historicized artists like Ahmed Mater, who has been working for years on how we interpret reality through the evolution of media, to Muhannad Shono, who works with organic and technological materials, from Ayman Zedani on Anthropocene themes, or Sarah Brahim, who uses analog technologies to reflect on how we interpret reality. The artistic scene is increasingly complex and varied, often engaging traditional and more technological media. The interesting factor is that these artists are developing a very innovative language, as they not only experiment with more advanced materials (digital media, for example) and more belonging to their culture, but are also developing themes and concepts in new ways, I think of how they approach themes such as spirituality, social changes, new perspectives on man.

CS: After these intense years, what do you feel you have learned, as a curator and as a person, from this experience? What advice would you give to those who want to work today in a cultural system under construction like the Saudi one?

VC: International work has given me a lot, especially if developed on two continents and two completely different cultures. I have not only met new artists, new curators, but I have learned new practices and developed a different vision of art. Collaborating with Sony Lab in Paris I learned how important it is to unite different worlds, like art and innovation, and how to develop research projects through art. In Manchester I certainly learned a new dynamism, and the ability to unite exhibition projects with innovative forms of production and education, and a different relationship with the public and environment.

While in the Middle East I had to confront a new culture, with artists who have developed research apparently far from what I had studied but actually very close. Building increasingly large and visionary projects, building institutions for the future and for future generations. Fundamentally, all this has helped me conceive the museum and art differently, not making exhibitions for myself, but thinking about how my research can speak to an audience, how to attract new projects and therefore new funding. Attracting new actors into the art world, as I tried to do with the exhibition “Euphoria. Art is in the Air” at the Grand Palais, for example, an exhibition that is doing 5,000 people per day! A way, therefore, to respond to the crisis of contemporary art and demonstrate its importance today and in the future.

Constant research, innovation, not being afraid to go into less traveled territories that are often complex or judged unsuitable – this is what I would advise young curators.