As some of nature’s most exhibitionistic spectacles, flowers have evolved to master the art of seduction — whether for luring pollinators or ensnaring prey — as a means of survival. In her latest film, The Book of Flowers (2023), Agnieszka Polska employs a similarly seductive strategy. Polska, collaborating with generative AI, traces a fictional history of human-flower entanglement, from symbiosis to hierarchy. In doing so, she holds up a mirror to our present, charting the rise of the techno-capitalist complex and its symptomatic depletion of socio-erotic and ecological relations.

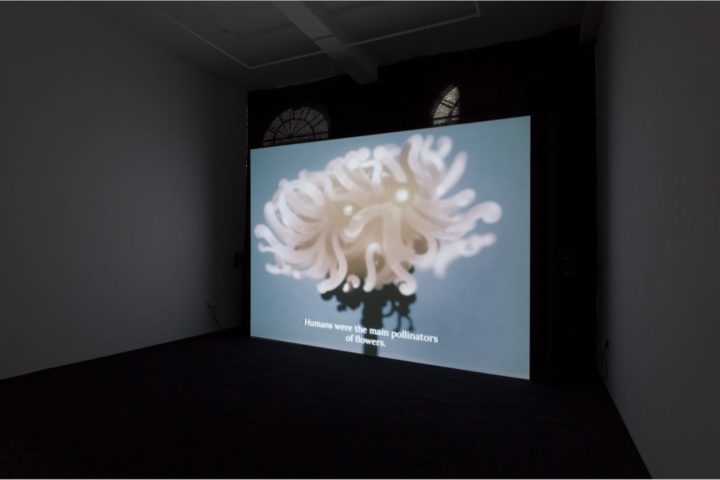

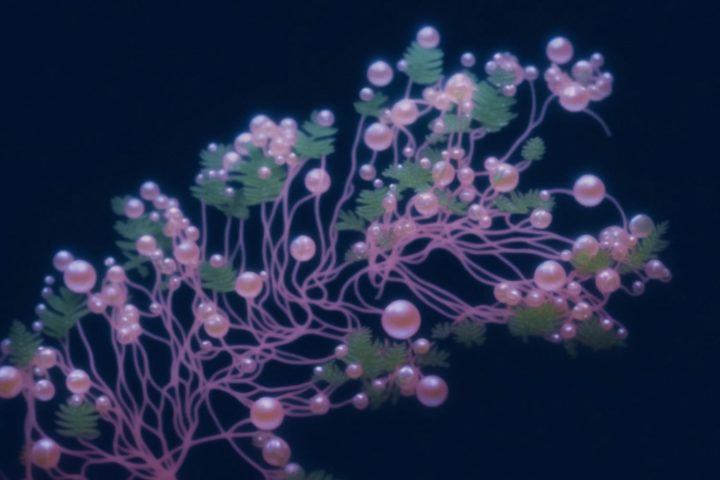

Now showing at Union Pacific’s Covent Garden space, The Book of Flowers is a ten-minute, visually lush, trippy, sexy, subversive ecofeminist sci-fi documentary, narrated in Christina Greatrex’s pristine British accent. To create it, Polska used Stable Diffusion AI — a text-to-image model you may recognize from creepy celebrity deepfakes — feeding it with her own text prompts and found 16mm time-lapse footage of blooming flowers (some of the earliest ever recorded). The result is a shifting floral uncanny valley — sometimes evoking biological processes, particles, or microorganisms; at other times, flickering with streams of code like an alien language or genetic blueprint. This psychedelic landscape unfolds within an atmosphere of religious reverence that is underscored by Charles-Marie Widor’s nineteenth-century Symphony No. 5 Toccata for Organ. The film’s hypnotic allure is heightened by its visual and rhetorical juxtapositions — oscillating between archaic and futuristic, romantic and clinical, hyper-specific and mysterious, sacred and profane.

Greatrex’s reassuringly authoritative voice introduces a story of “want, misery, horror, desire, fantasy” — though the horror, we soon learn, is mostly reserved for the men. Enormous flower cups were once sites of rest, lovemaking, and procreation for early humans. Naked bodies served as pollen disseminators, while spores were carried by male sperm into women’s placentas, birthed together with human babies, resulting in a gloriously monstrous, Donna Haraway-ian sympoiesis and interspecies mergence.1

Heteronormative gender roles (categorized as “male” and “female” in the film) are flipped. Mythical early mothers embark on solitary pilgrimages to give birth, inventing the first tools and the first stories. (The tales of non-mothers, perhaps barren, or just uninterested, remain untold.) Meanwhile, the role of males within the ecological cycle is decidedly more fatal. They are “poisoned and dismembered” after sex, consumed by the flowers — a “satisfying end” and “natural conclusion of desire,” coded with a mixture of Bataille-ian transgression2 and a rather extreme sub-kink. Males ruminate over their inevitable demise through a new literary genre of the “ecstatic self-eulogy,” with one anonymous voice going as far as to imagine, in the quasi-blasphemous treatise The Book of Flowers, the possibility of exchanging his soul to escape consumption. Polska resists deterministic conclusions, leaving us with open-ended questions about evolution, progress, and the soul.

The film’s next act ushers in humanity’s domination over flowers through technologization, marked by a shift in imagery: juicy, shimmering flowers intercut with clinical laboratory machines, drills, and tubes. Polska rejects escapist cyber-utopias, instead exposing how capitalism’s extractive logic shapes the infrastructures of desire and society. Flowers are burned en masse to fuel steam engines, exposing class hierarchies as the working class loses access to flower cups, leading to declining birth rates. Technological advancements drive mass flower production for food and energy, while procreation outside the cups — once a perverse fetish — becomes “humanitarian necessity,” spurred by social media. Humanity’s alienation from nature is complete, giving way to the anthropocentric, techno-capitalist order of our own present, poignantly diagnosed by Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi as the “age of impotence”3 — a state of collective alienation and apathetic depression. According to Bifo, this condition may only be overcome by rekindling sensuous consciousness within the “oases of friendship, love, intellectual and erotic sharing, conspiration, and the projection of a common landscape,” – a vision that The Book of Flowers seems to embrace.

In its final moments, the narration shifts to Polska’s true meta-protagonist: our stories themselves. Greatrex issues an ominous warning about time and progress accelerating beyond our control, suggesting that, in the end, our stories may master us — “leaving us captivated, speechless, and shrunken, as tiny as a daisy.”

Informed by her upbringing in communist Poland, where the state instrumentalized dominant ideological and cultural narratives to reinforce power structures and collective values, Polska’s interest lies in interrogating the gaps and glitches in the seemingly monolithic stories we are presented. Here, what remains concealed is as significant as what is visible. The Book of Flowers directs our gaze to the flower — the most spectacular and conspicuous part of the plant, explicitly linked to procreation — while simultaneously teasing us with omissions, open-ended questions, and shifts between infra- and metanarratives, inviting us to consider what lies beneath the plant’s hidden structures. Most importantly, perhaps, is how this functions as a subversive reflection on the medium itself. Generative AI operates through an infrastructure of concealment, obscuring its training data and built-in biases. Studies on Stable Diffusion, for instance, have exposed racial, cultural, and gender-based biases, acknowledged by its developers and examined in a 2023 Bloomberg case study.4 AI’s reliance on extraction, invisible labor, and ecological harm (Stable Diffusion’s training reportedly emitted thirteen metric tons of CO₂)5 is hidden beneath glossy pixels.

By making the story itself her subject of critical inquiry, Polska extends beyond Donna Haraway’s call for radical storytelling as a counter-hegemonic act. She prompts us to look beyond and beneath the seductive digital spectacle of the flower cup, and to question whether the medium through which our stories are disseminated is as fundamentally determinative as their message.