Silvia Federici once wrote that “the body is a factory.” For the body to not work — can’t or won’t — is to exist outside of capitalist society. In “My Weaponised Body,” at Gathering in London, Wynnie Mynerva reckons with the beauty and the violence of the body and the beauty and the violence of a body regarded as sick and thus not working — profanely so. Mynerva writes that “to be HIV positive is to be sick with meanings, infected by the assumptions society projects onto my body.” These assumptions are political, sexual, social, and, as Federici reminds us, labored. Rather than fall prey to a capitalist rhetoric that deems people fit or not for a purpose, Mynerva, like Federici and the proletariats, vagabonds, and artists that have come before, seeks to transform the body from a cog in a machine to an autonomous, and collective, state; one that challenges what it means to “work” or not through a frenzy of strange biomorphic shapes that push up against the edges of painterly composition and the structure of human anatomy.

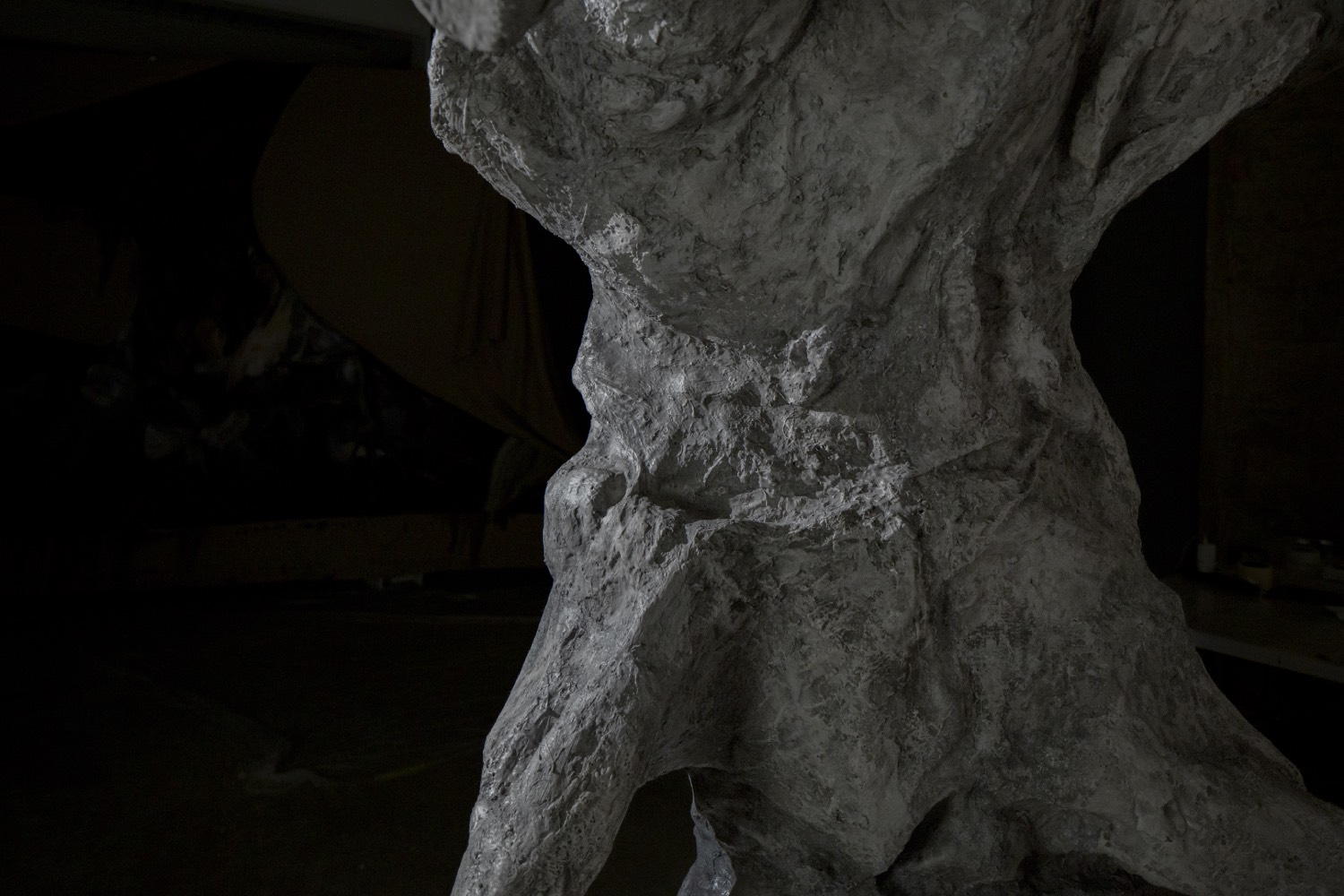

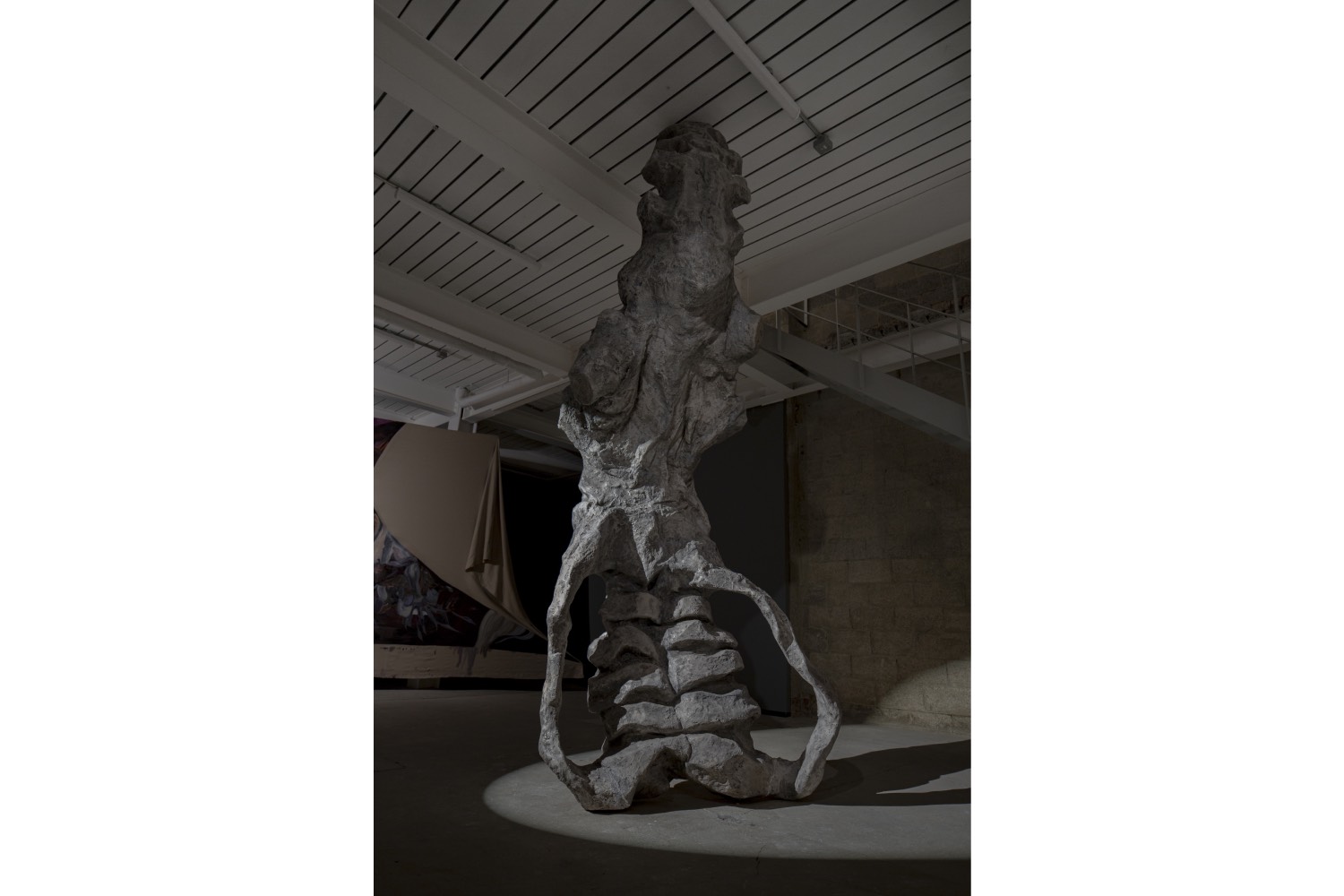

Mynerva was born, and lives, in Peru, but these canvases were made between a recent residency in Amsterdam and the gallery space at Gathering in the weeks leading up to the show. The works began life on conventionally stretched canvases before being dismantled, detached from their stretchers, and then stretched again using metal wires drilled directly into the ceiling and walls of the gallery. Strung up like flayed bodies, Mynerva’s unprimed linen canvases take on the quality of skin but also sculpture, drawing them closer to the show’s three-dimensional work Hueso (2024): a spinal cord — rendered in resin, fiberglass, polyurethane, Tecnopor, and metal — devolved of flesh that snakes between two floors of the gallery.

In the accompanying text, Maria Inés Rodriguez returns us to Federici: “Our bodies bear the marks of the pains and joys we have experienced, of the struggles we have fought. Like an open book, bodies speak of oppression and revolt.” As for bodies, so for painting. Presented in the dark, sometimes subterranean gallery space of Gathering, works like Transmutacion (2024) and Prejuicio (2024) are striking in their fleshly, and thus durational, quality. Mynerva builds oils thickly sustaining a wetness, like bodily excretion. By doing so, the artist remind us that the body, like good painting, is a durational state — perpetually changing, transitioning, losing and gaining fluidity and structure; immunity, energy, virility; something that Mynerva has felt more acutely since their recent HIV diagnosis. What they seek, they say, is to transform the presence of the virus into a language — “to name where I am and where I am not.” This movement between presence and absence manifests in the elliptical spaces and loose corners of unprimed canvas that Mynerva leaves exposed, and in the ways in which the painterly composition rarely meets its splayed and stretched edge. But it happens within the painting too: limbs and torsos emerge from and disintegrate into a chaos of gestural strokes that tesselate between figuration and abstraction while also defying gravity.

Mynerva studied art history before they studied painting. The scale (spanning the room), form (elliptical, recently, for the vaulted ceiling of Fondazione Memmo in Rome), and style (exalting bodies) of their canvases chew up and spit out the art-historical canon: at points the corners of the canvas drape down like the baroque folds of curtains meeting the baroque flourishes of Mynerva’s fleshly marks and dark impenetrable spaces. Persistent strokes like flower petals in bruised violet, fawn brown and pink build to a muscular calf or soft stomach, before decomposing into lifeless taupe and dull pewter gray. What was once vibrantly baroque recedes here into dark, fiery Blakean hellscape; a reflection, perhaps, of how the artist feels, or society feels, about their body post-diagnosis. The risk of reducing a feeling to tonal darkness is thwarted by Mynerva’s hyper-saturated form: undulating lines in ultraviolet or profane pink extend into black lacquered talons — neither straightforwardly bestial nor human, man nor woman, and bursting forth from the picture.

Mynerva’s work is at its best when it bears witness to their own body, but also to the violence of heteronormativity, which manifests figuratively through the reoccurring presence of Lilith. As the first wife of Adam, Lilith was banished from the Garden of Eden and became emblematic in Abrahamic faiths of a fallen woman: demonized, sexualized, fetishized, and perpetuated, so that the talons in Mynerva’s work, we might surmise, belong to her. “Lilith and Eve pose as ‘female’ archetypes, reframed as powerful symbols of sexual insurgence and united by their inability to satisfy male expectation,” says the text that accompanied Mynerva’s previous show at Gathering.

“My Weaponised Body” implicates the body and painting in a kind of politics of failure — or not working — by extricating bodies from the conventions of a pictorial frame and thus male expectation. Mechanical philosophy, Federici writes, conceives of the body “as brute matter, wholly divorced from any rational qualities; it does not know, does not want, does not feel.” Mynerva reimagines painting not as an imitation of brute matter but as an extension of it into feeling, the here and now of it; knowingly incomplete.