SoiL Thornton’s practice embodies Glissantian opacity, engaging in a play of misunderstanding and ambiguity. It’s open to the indefinable yet enclosed in a private vitality that resonates us all. The exegesis of Thornton’s work is complex, untangling psychological and emotional tensions of the Self — accepted as it is, undefined, unfinished, but left in its marvelous indecipherability and multifaceted nature. “Candidate Screening Methods”, Thornton’s first solo exhibition at Progetto, Lecce presents the Self: theirs and ours, mine and yours, the unique self of each of us. We are similar in structure but different in infrastructure: shaped by experiences, traumas, and social, political, sexual, and psychological influences. Both we and the artist, caught in solitude, opening ourselves to others while remaining opaque, dissolving into the works presented in the space.

The title of the show — the first in Italy — hints a methodical “recruitment” carried out by the artist on individual identity through twenty-four framed photographs and a large installation at the center of the main room. While the subject remains veiled, it allows an immediate connection with the private dimension of Thornton’s work, which is deeply hermetic in its relational complexity and indefinite openness that commands the viewer’s attention.

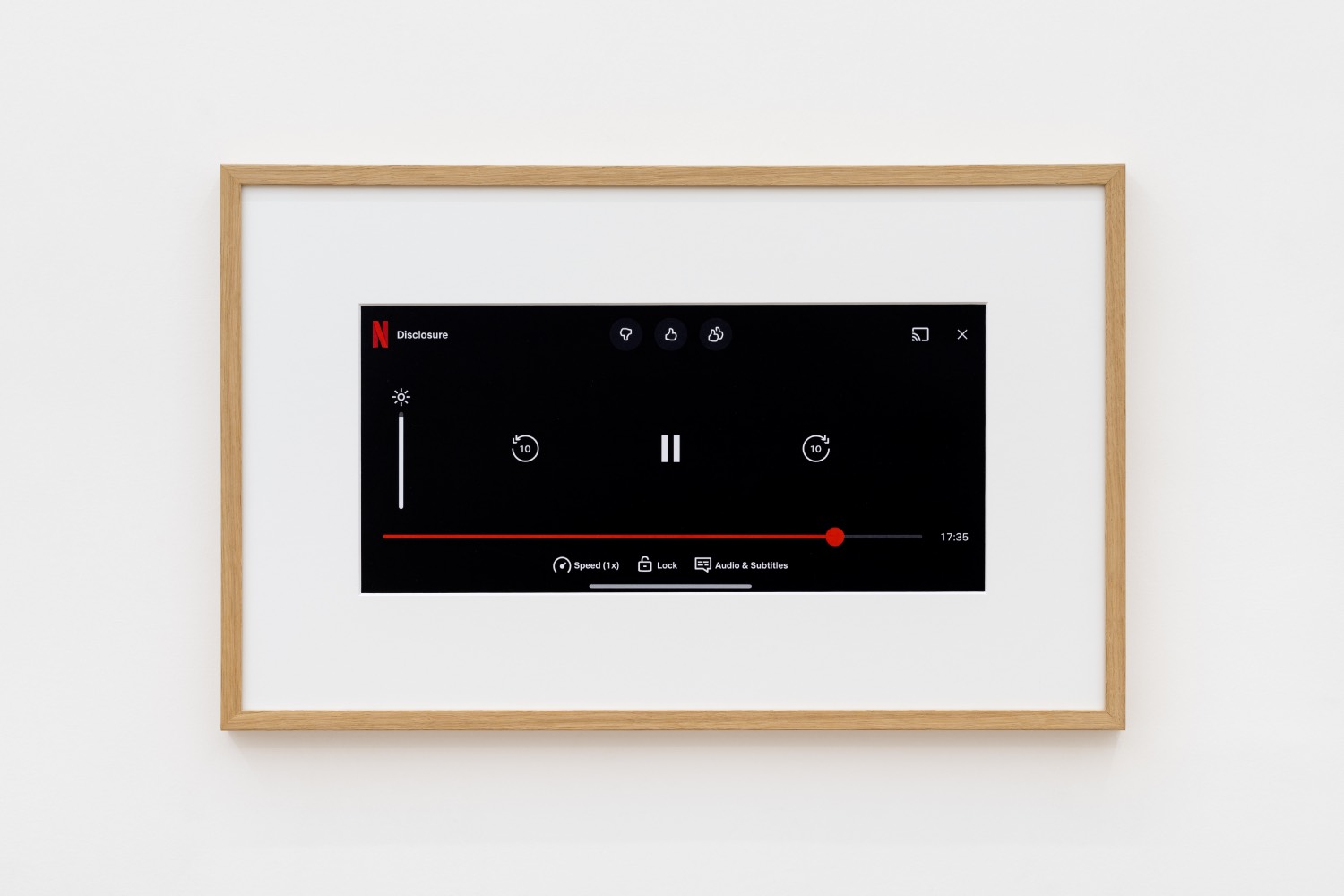

The experience is muted, with an evident sense of obscurity created by the artist. As we move through the rooms, we encounter a series of screenshots from films and documentaries Thornton watched on Netflix both in the US and Lecce, without using a VPN, bound by commercial agreements. These images are denied photographs because the DRM (Digital Rights Management) restrictions imposed by streaming distribution companies prevent the free sharing of films, leaving a black and silent image with only the outline of the interface visible. The work, titled 186,282 miles per second enabling 24 frames per second revoked, OR, Digital Rights Management (DRM) mirroring a rapid eye movement (REM) frame (2024), depicts nothing but the interruption of those twenty-four frames per second caused by a snapshot traveling at the speed of light. This narrative thread highlights the psychological suffering of the individual is secondary to the empty silence of our minds that awakens in that instantaneous snapshot, allowing us to imagine beyond the screen.

“It is black. It is dark. You feel locked inside”.1

In the second room of the gallery, chromosomal discrepancy bridge (2024) serves as an obstacle. The installation is made of colored wood and constructed with brackets typically used as urinal dividers, arranged here as a barrier — a partition between the corridor and the repressed nook of the room where three photographs are partially covered but visible. The structure wrapped in a transitional UV photochromic lens creates a slight distortion of colors and perception, constantly changing and altering its coloration, — from transparent to violet — representing the shades of mood and identity, forming a bridge to the inaccessible.

Although the theme of image obfuscation is clear, the investigation is deeper, probing the hidden compartments of one’s intimacy, nuance by nuance, without ever fully defining them. The title of the installation and the exhibition — chromosomal discrepancy bridge and “Candidate screening methods” — use medical terminology as a metaphor for medical records. However, instead of treating chromosomal mutations the work methodically analyzes the complex psyche of the individual, focusing on sensations and thoughts. It explores how protean identities are now being addressed and homologated within common escape systems just like Netflix. The exhibition screens experiences moods, and sensations, highlighting the endless personal modifications that we each undergo in unique ways. We face the coldness of our own gaze, becoming both the “guinea pigs” — used “to explore or analyze societal precarity, oppressive infrastructures or even complex pleasures”2 — and our own voyeurs.