In the text accompanying Oisín Byrne’s exhibition “Smell the Book,” writer Daisy Lafarge asks, “How does language make you feel?”1 Lafarge, ever the meticulous wordsmith, intricately maps out the enveloping uncertainties of language and how it shapes experience and perception. Lafarge positions language as a suggestive placeholder — open to interpretation and meaning. Language is inherently suggestive albeit a necessary tool. It acts as a glue, often binding a culture together. Samuel Beckett apparently once wrote, “Words are all we have,” 2 capturing the deep paradox of language: it is both a delicate tool for expression and an imperfect medium for conveying meaning. Perhaps, this paradox is at the heart of Oisín Byrne’s latest exhibition, “Smell the Book,” where the tensions between language, literary histories, and form are explored with both playfulness and depth.

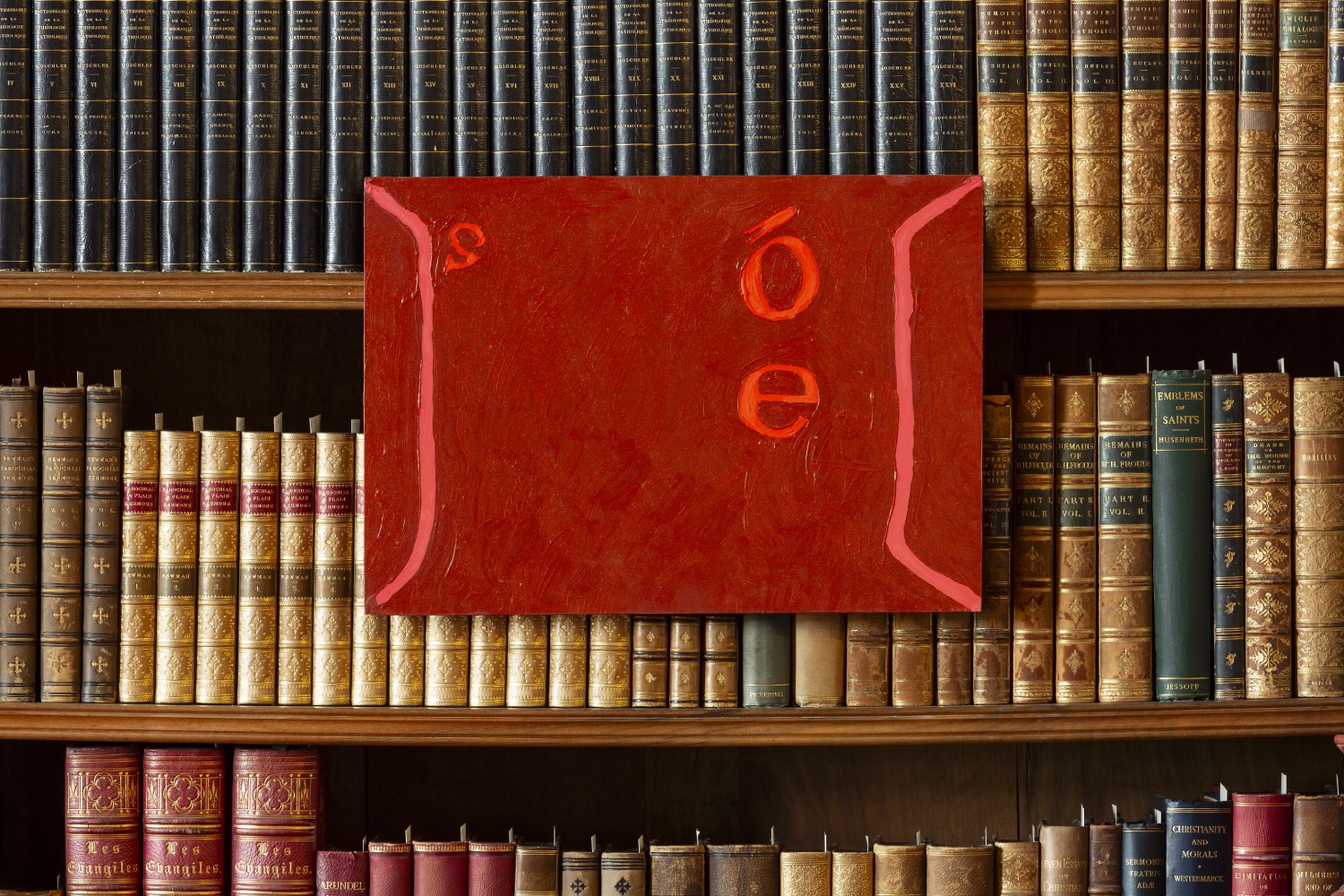

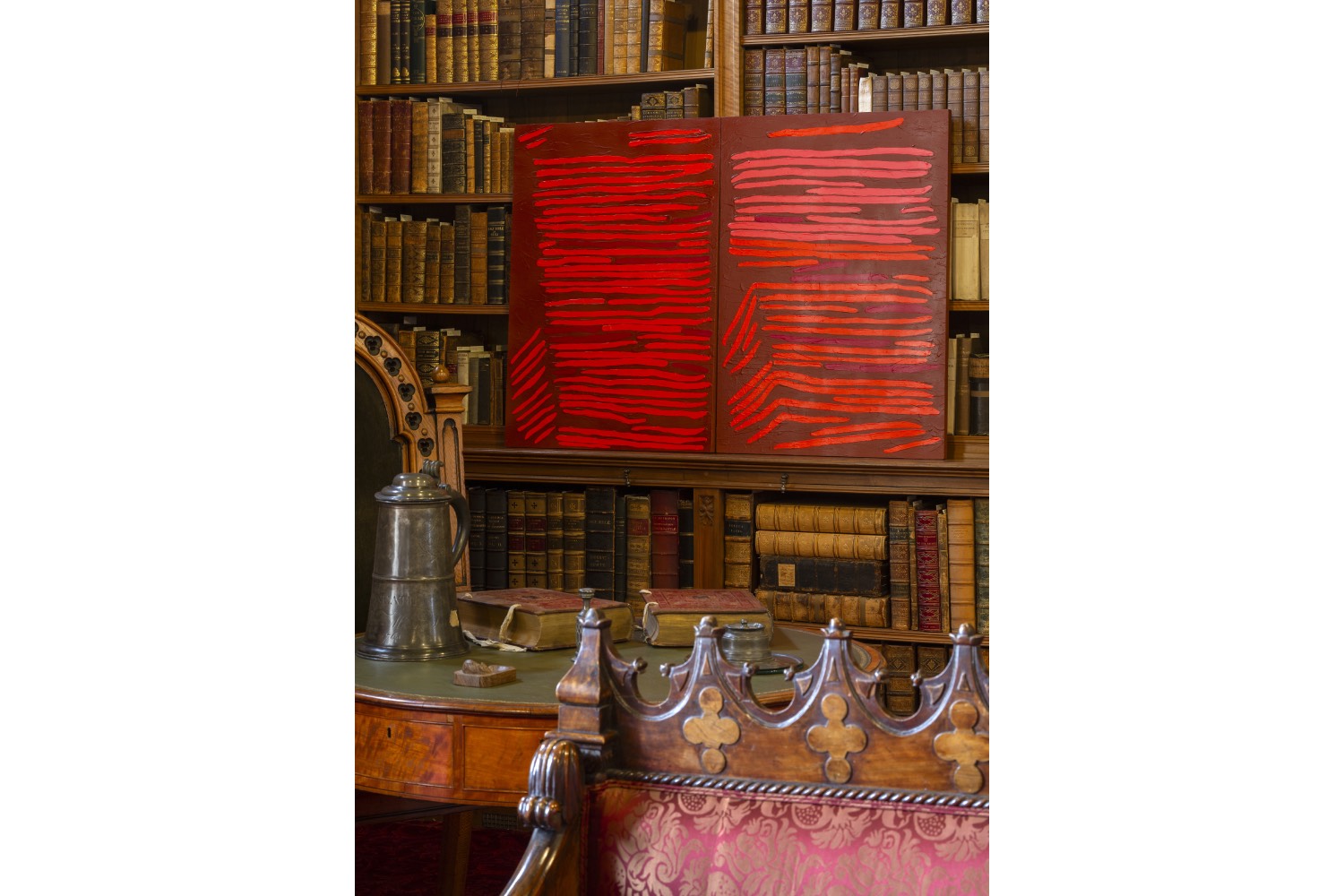

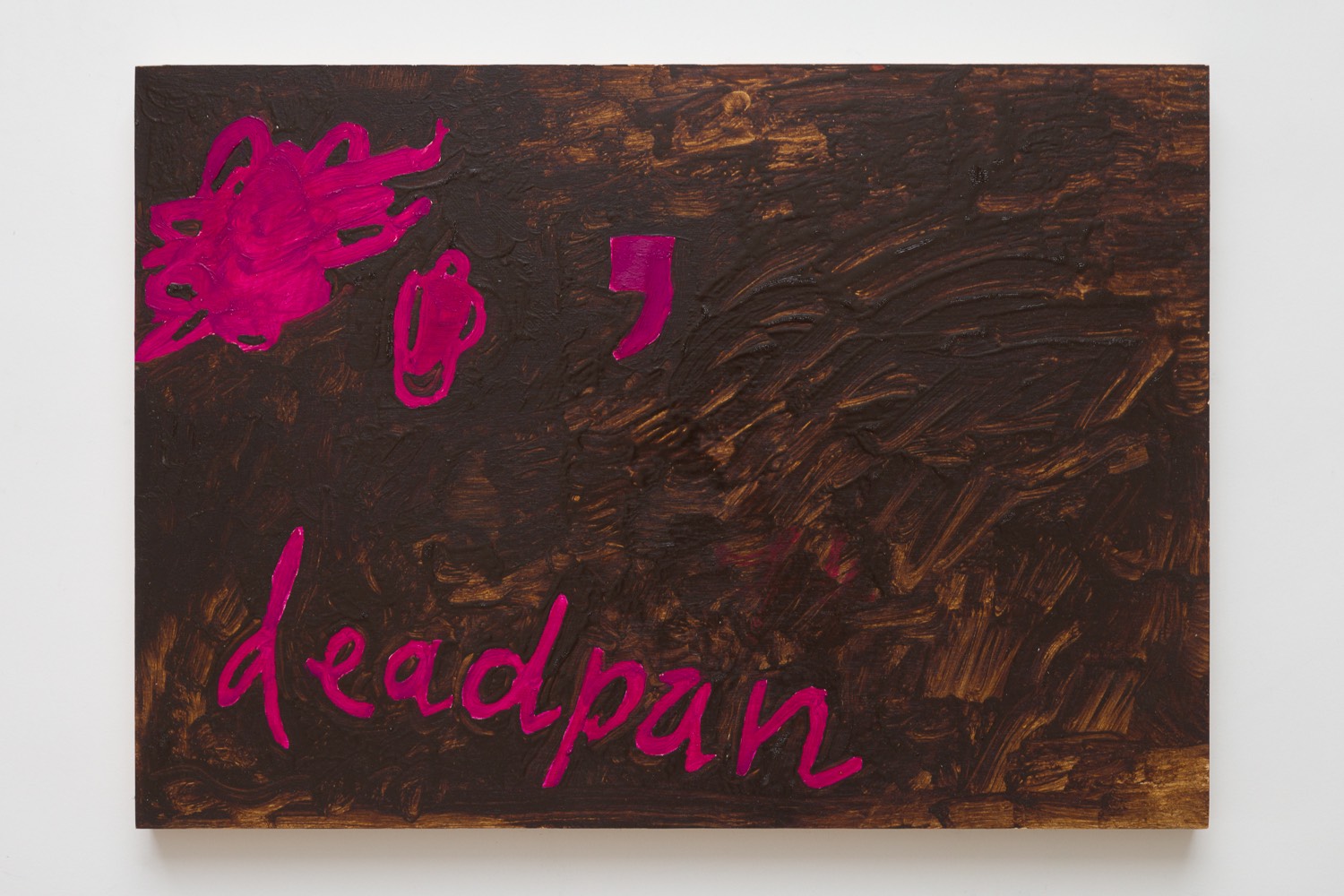

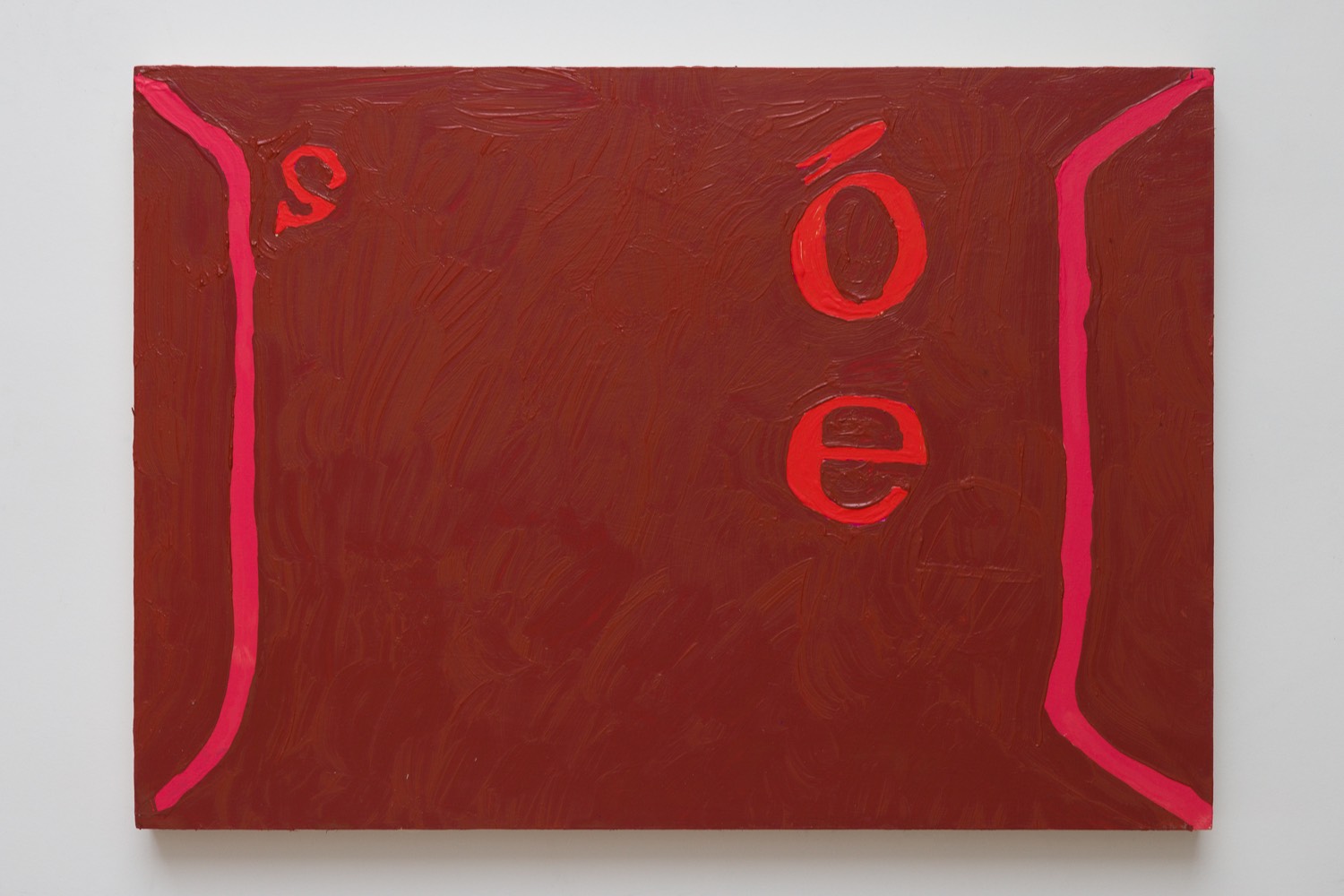

The exhibition takes as its starting point a lesser-known collection from the Mount Stuart archive: its Gaelic and Irish books and pamphlets alongside some of Byrne’s personal collection of books. In Byrne’s hands, these texts become generative ground for artistic intervention, where the written word is transformed into a visual and highly sensory experience through painting, writing and song. Byrne’s new series of paintings intricately interlace archival markings and glyphs with the handwriting and graphological imprints of literary figures from both the collection and his own personal library, drawing inspiration from the works of Flann O’Brien, James Joyce, Clarice Lispector, Doris Lessing, Susan Sontag, and Frank O’Hara. Though distant from the Gaelic texts which are pointed towards, these interlopers become vital participants in the dialogue Byrne conjures, forging a conversation that transcends languages, eras, and cultural boundaries.

“Smell the book” contains many interrelated parts positioned around the building. The building itself, Mount Stuart, is a prominent neo-Gothic mansion located on the Isle of Bute, Scotland. It was built in the late 19th century by the 3rd Marquess of Bute, a wealthy aristocrat, and is known for its extravagant design, stunning architecture, and beautiful gardens. The house is one of the finest examples of Victorian Gothic architecture and has become a popular tourist destination. The house features a private chapel, impressive marble interiors, and one of the world’s first homes to have an indoor heated swimming pool. Since 2001, Mount Stuart has played host to a unique Contemporary Visual Arts Programme. This decadent and unconventional space has become a source of inspiration and a venue for exhibitions of international calibre, helping to cultivate a broader appreciation for contemporary art in the region. Among the artists who have contributed to the programme are Martin Boyce, Sekai Machache, and Monster Chetwynd.

At the centre of the exhibition, within the marble hall, lies a series of six oil paintings on linen titled “Glossia” (2024). These works, highly textured and elusive, capture fragments of letters drawn from the words glimpsed on the covers of books in the collection. The hues in these paintings seem to draw inspiration from the rich tapestries and intricate design of the hall, weaving the space together. Suspended from metal stands built for the exhibition, the paintings appear to float, like disembodied voices lingering in the air, giving shape to the boundaries of speech — the jagged edges of words, the guttural rhythms and cadence of a voice. Byrne hints that their forms might mirror the shape of a throat, though to this viewer, they more evocatively resemble the spread of an open book, inviting, a welcoming.

Ascending the stairs of the marble hall, the viewer is met with a moving-image piece originally commissioned by the National Sculpture Factory in Cork, Ireland: A PAIXĀO (2022), situated in the Victorian Bathroom. In this work, Byrne reclines in a bath, seemingly recounting a fictional encounter with the Ukrainian-born Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector. AI-generated flashes of Lispector’s penetrating gaze flicker between moments of Byrne singing in the bathtub, eyes closed, perhaps performing an imagined memory. This work serves as a light anchor, providing visitors with insight into the methodologies underlying Byrne’s practice. The work positions the interplay of various mediums, while fore fronting song as central to Byrne’s expression. Byrne’s practice often intertwines fragments of overheard conversations with personal reflections, drawing from an extensive collection of notebooks which contain thousands of collected phrases. Byrne’s works often appear to make visible the messy act of writing, the gaps between a thought and what is said or put onto the page. The space of mediation is wide open, taking in the work, I’m thinking about what to write about the work, how am I understanding the work? The realisation occurs that often an encounter with a work of art is the impetus of an act of writing in and of itself, as a means to understand. Here, Lispector’s text The Passion According to G.H. (1964) comes to mind, as she put it, “I write to understand as much as to be understood.” 3 This sentiment resonates with Byrne’s approach, emphasizing the transformative power of language and the search for meaning in the everyday.

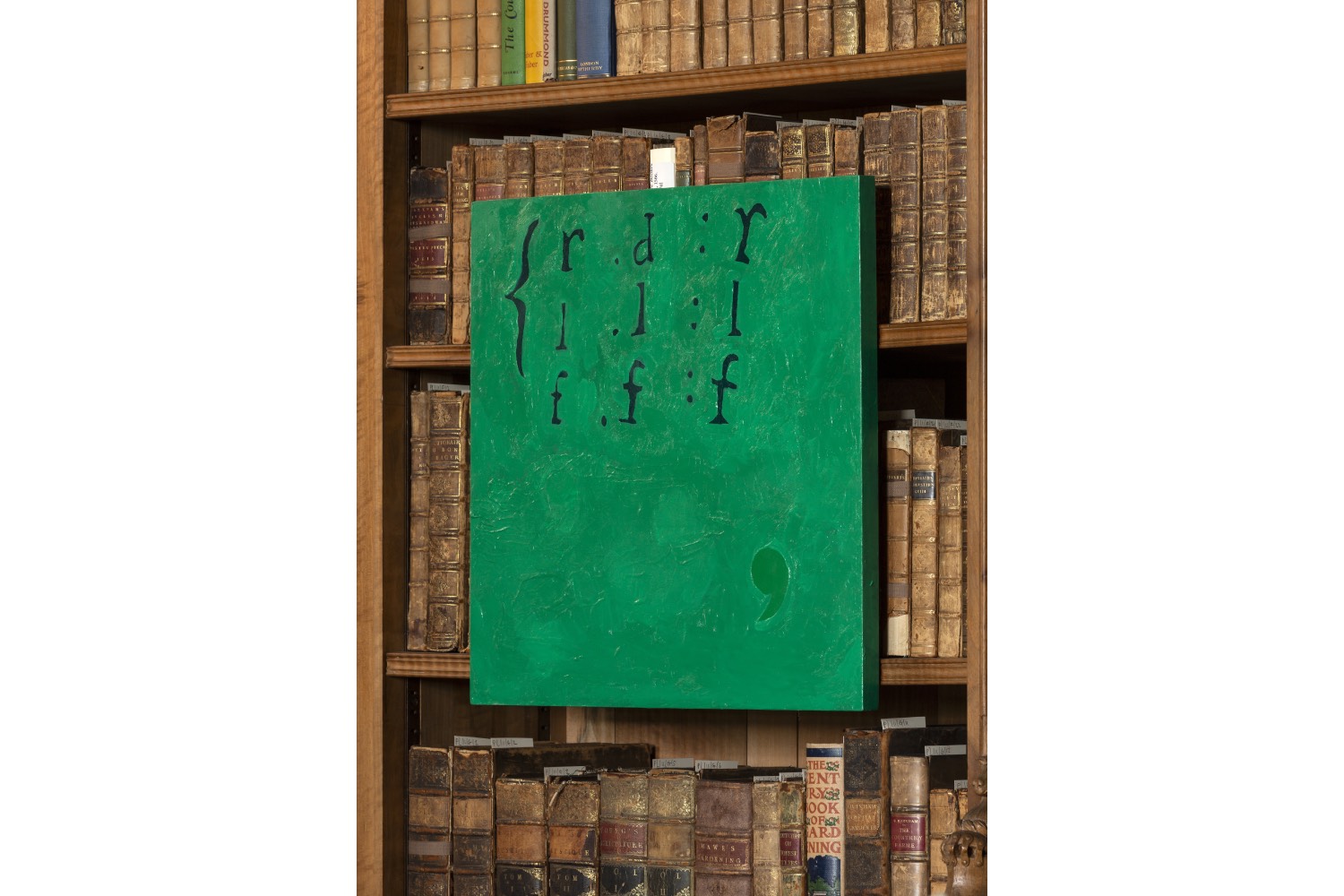

Among the most surprising elements of the exhibition is the Marble Chapel, which houses several works that unfold like a theatrical performance. CRÍOCH (2024) sits provocatively in front of the altar, a choice that inevitably invites a broader political interpretation of the exhibition, regardless of the artist’s intent. By placing a painting in front of the altar – essentially obstructing it – the act becomes inherently political, if subtly so. This gesture evokes the display of Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square at “The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0.10” (1915–16), where, drawing inspiration from the Russian Orthodox Church, he hung his work in the most sacred space of the room, symbolically displacing an oppressive presence. One cannot help but perceive Byrne’s choice in a similar light. Moreover, críoch is the Irish word for “end.” This vibrantly green painting, which proclaims “end” in a language systematically dismantled and destroyed by a colonial oppressor intertwined with religious ideologies, deepens the political implications of its placement.

Also housed within the chapel is a 17-minute video work, Quartet (2024), which features three of Byrne’s songs playing through out the work. The film was shot on 16mm Film on a Bolex in Byrne’s studio with a quartet. The songs, one titled “UNPERFORM” suggest an alternative, materialistic ritual in a space of traditional worship. The sound from the work comes from speakers hidden in the architecture of the altar.

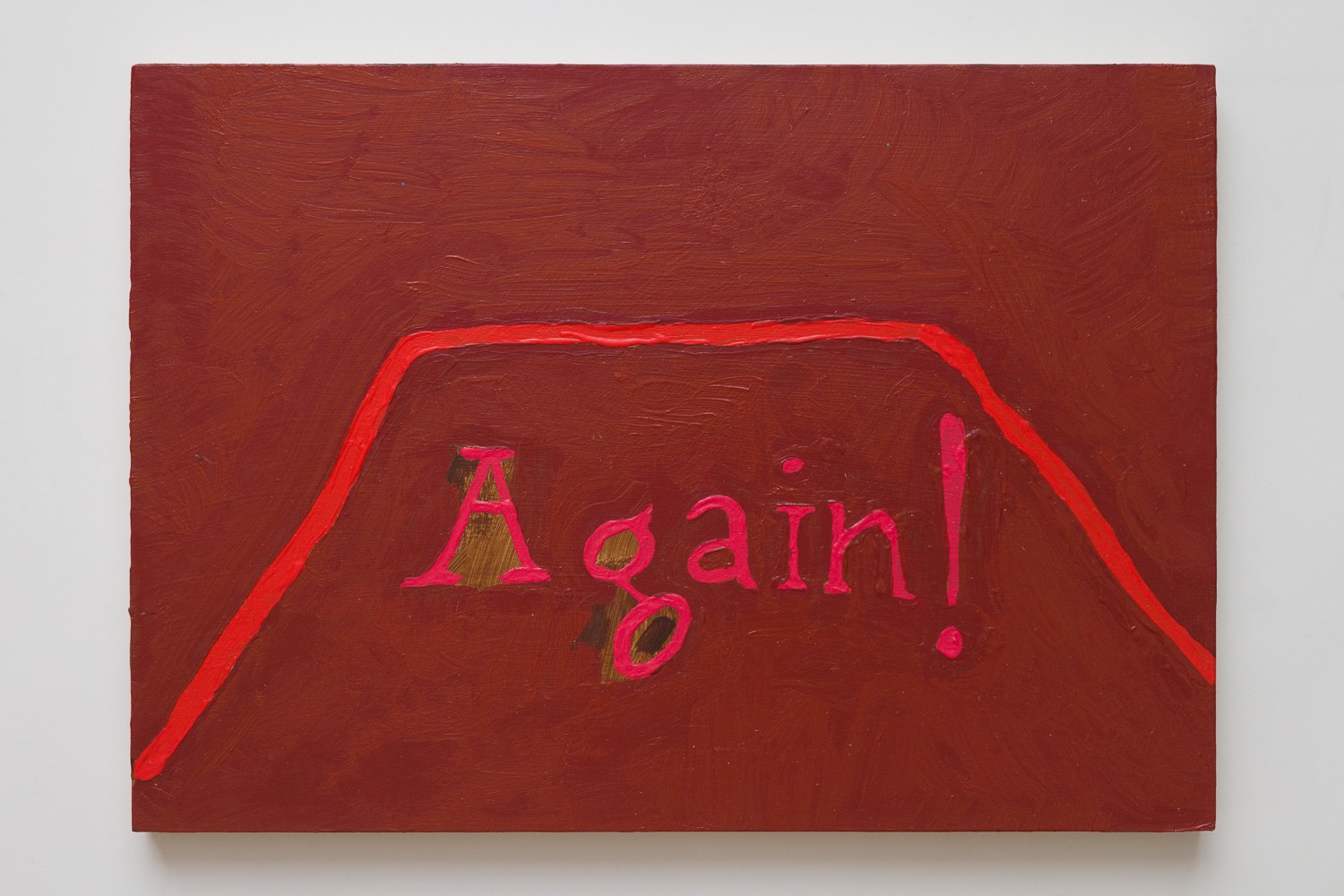

In these works, Byrne embraces what Susan Sontag calls “an erotics of art,”4 a notion she develops in Against Interpretation (one of the books referenced in the collection). Sontag argues that art should not be reduced to mere intellectual interpretation but rather experienced viscerally, as a sensory engagement. Byrne’s performances and performative objects embody this philosophy: language becomes texture, form, and rhythm, liberated from the rigidity of meaning.