What is immediately striking about Nick Goss’s work is the subversion of the perspective, which shifts from piece to piece, driven by a subjective, often angular vision and the study of flatness, doubly subverting any possible leanings toward pictorial neo-academicism. This approach draws some comparisons to Matisse, as it tends to become a study of the support and the surface itself. Similarly, Goss’s use of a fine, dense layering of meanings – intertwined with hybridized materials and techniques, such tempera, oil, and silkscreen – creates a visual and intellectual (post-retinal and para-turpentinian) shock.

In its apparent simplicity and minimalism, Sun Cafe (2024) creates this effect of sensory and mental unease by subtly superposing layered hints, structures, stories and (hi)story, techniques, and angles of view, to flatness. On a large linen canvas, a section of the artist’s studio is depicted as a leader in the foreground. Arranged in an indeterminate angularity, the bay windows – suggested by the frames, painted in a Matisse-like blue – could easily represent the cockpit of a ship. Beyond the windows, a vast, nearly flat landscape, possibly silkscreened from an old engraving in navy-blue ink against a neutral backdrop, covers most of the canvas. With waves, mountains, and ancient buildings, this scene recalls an island reminiscent of the former Isle of Thanet, now part of to the British mainland, from which the exhibition draws its title.

The landscape of Sun Cafe seems to materialize a gaze into the past or a dream that exudes melancholy. Gross etymologically links Isle of Thanet to Thanatos, the Greek embodiment of Death. While this connection remains unconfirmed, it directly calls to mind Arnold Böcklin’s The Isle of the Dead (1827–1901) and its five versions (1880–86), which remain mysterious. Some of these works emphasize the island’s three-dimensionality and others, its flatness, with their sole, solitary figure being Charon, who ferries the dead to their final resting place.

At the front right of Sun Cafe, part of an eighteenth-century engraving from the Walburg Collection – depicting the Afrikaner hero Wolraad Woltemade on horseback, rescuing fourteen sailors from a shipwreck in Cape Town before he and his horse are swallowed by the waves – appears to be sucked through a trapdoor or through the studio’s wastepaper basket. Above, an office telephone with a large screen – or perhaps a computer and radio – hangs on the wall. A cable runs from a wall socket to a coffee machine placed on an angular stand, its liquid, clear as sunlight, pouring into a mug with silkscreened motifs reminiscent of a Cézanne pitcher. The angular coffee machine, symbolizing office life, underscores the solitude of the artist in the studio, or of a ship’s captain, who, like Wolraad Woltemade, makes decisions alone. It surreptitiously evokes Duchamp’s solitary Coffee Mill (1911) as well as Charon and his barque in The Isle of the Dead.

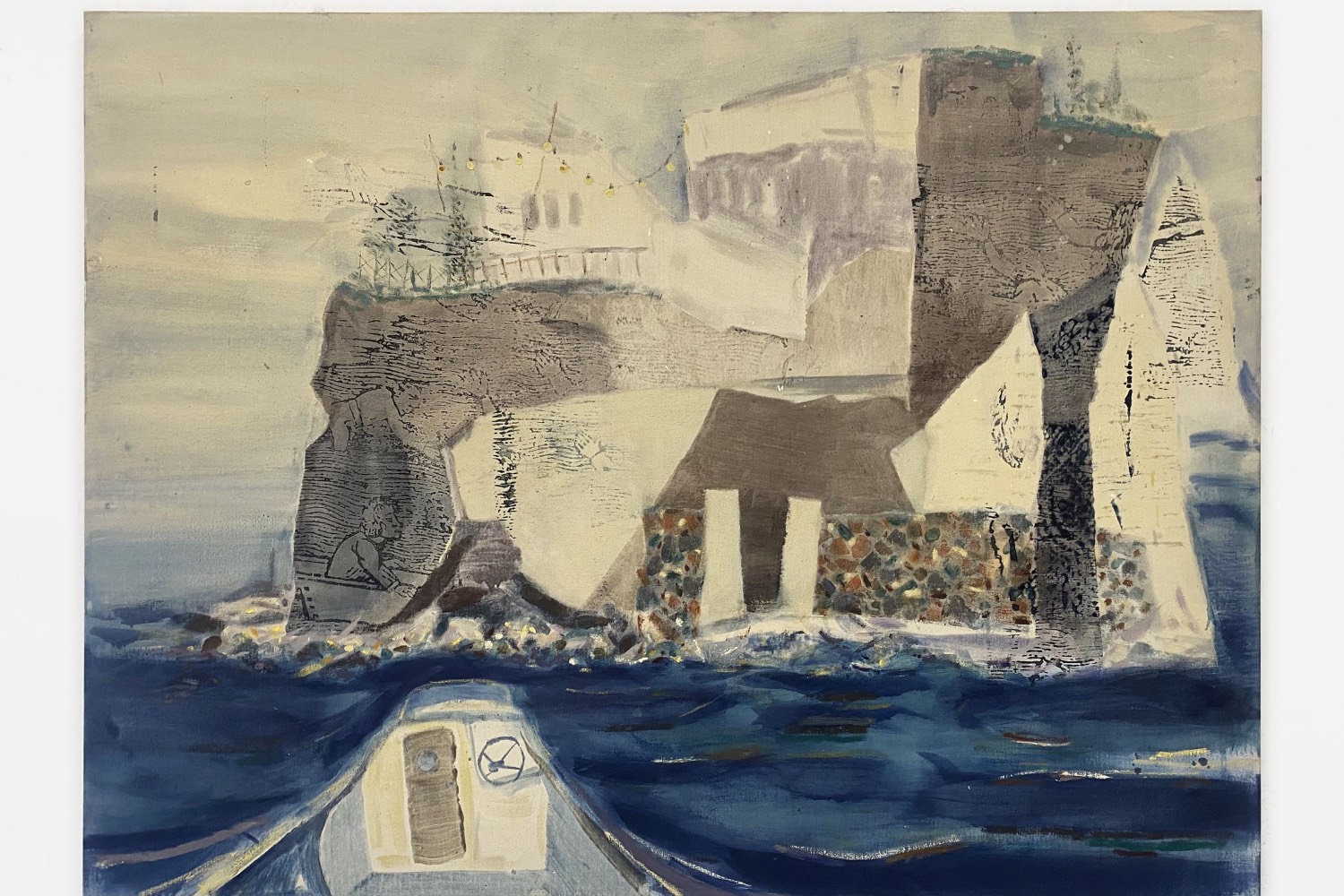

These multiple connections can be traced, directly or indirectly, throughout several works in the exhibition. Walpole Bay (2024) appears to revisit Böcklin’s Island. In this piece, Goss reimagines The Isle of the Dead, highlighting its massive three-dimensionality, angularity, and architecturally intricate form, while Charron’s barque seems to draw the viewer into the scene. The island appears to float in the distance, but the boat remains static. En Route (2024) further intensifies the inversion between the ship and The Isle of the Dead. Offshore, a boat seems to echo the contours of Böcklin’s island. Overloaded with passengers, it alludes to current tragedies at sea, once again invoking the figure of Wolraad Woltemade, or perhaps symbolizing the multitude of those who will inevitably find themselves on the Isle of the Dead. The land, possibly an island, is shown in the foreground, reversing the composition of the original work, and bringing it into the present –– or perhaps reducing the ship to a simple ferry, a modern symbol of overtourism.

Sun Cafe seems to distill the essence of the other ten large-format works – selected from the twenty pieces Nick Goss produced simultaneously in the studio as a part of this body of work – on display across the exhibition’s four rooms. The angular vanishing lines, layered interpretations of time and meaning, and the hybridization of materials all contribute to a disorienting experience for the viewer, mirroring the cohesion of the show. The unity is framed by a narrative thread: during a conversation with a curator who had recently moved to the area, Goss learned that parts of Kent were once part of the Isle of Thanet, creating further resonance between the works.

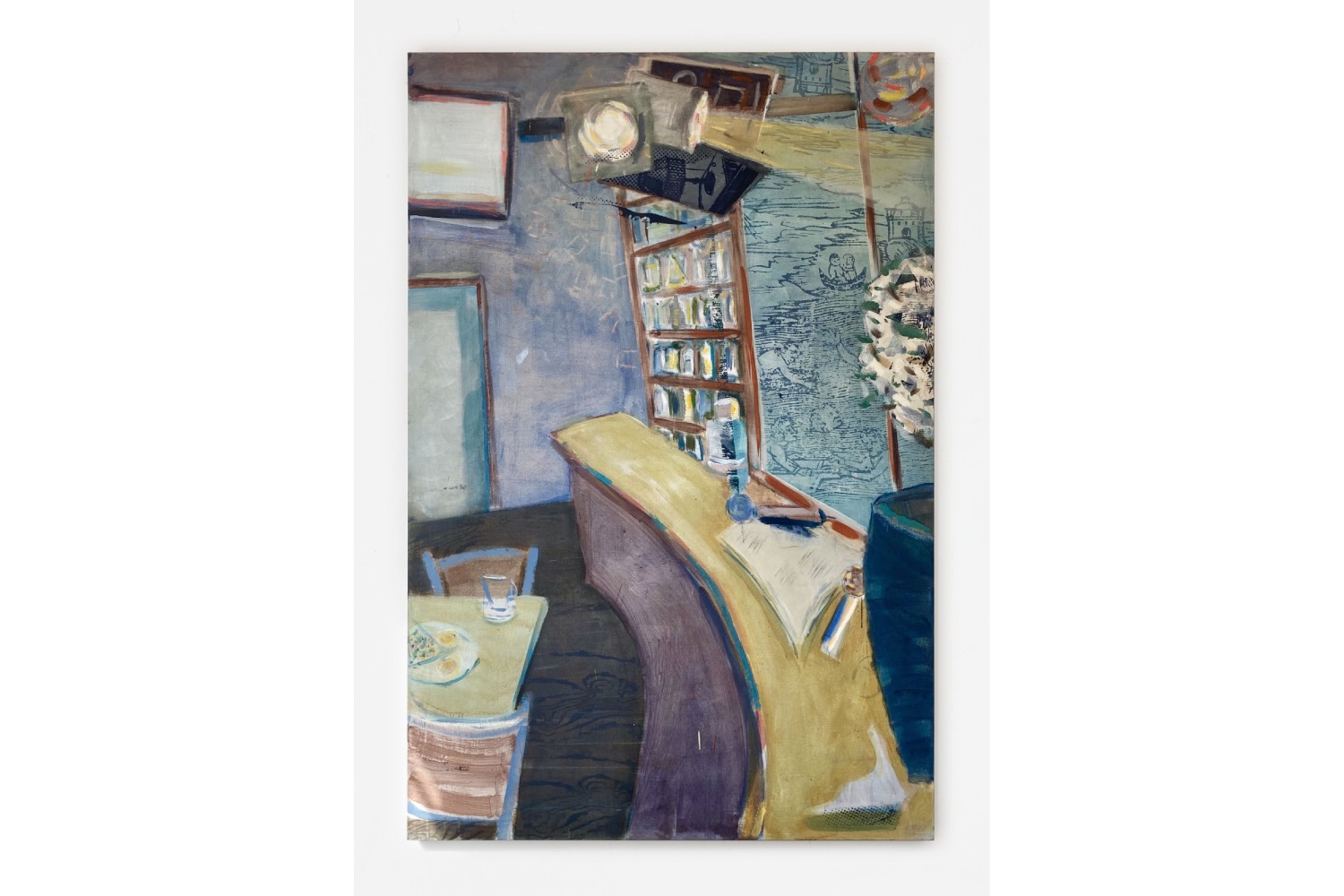

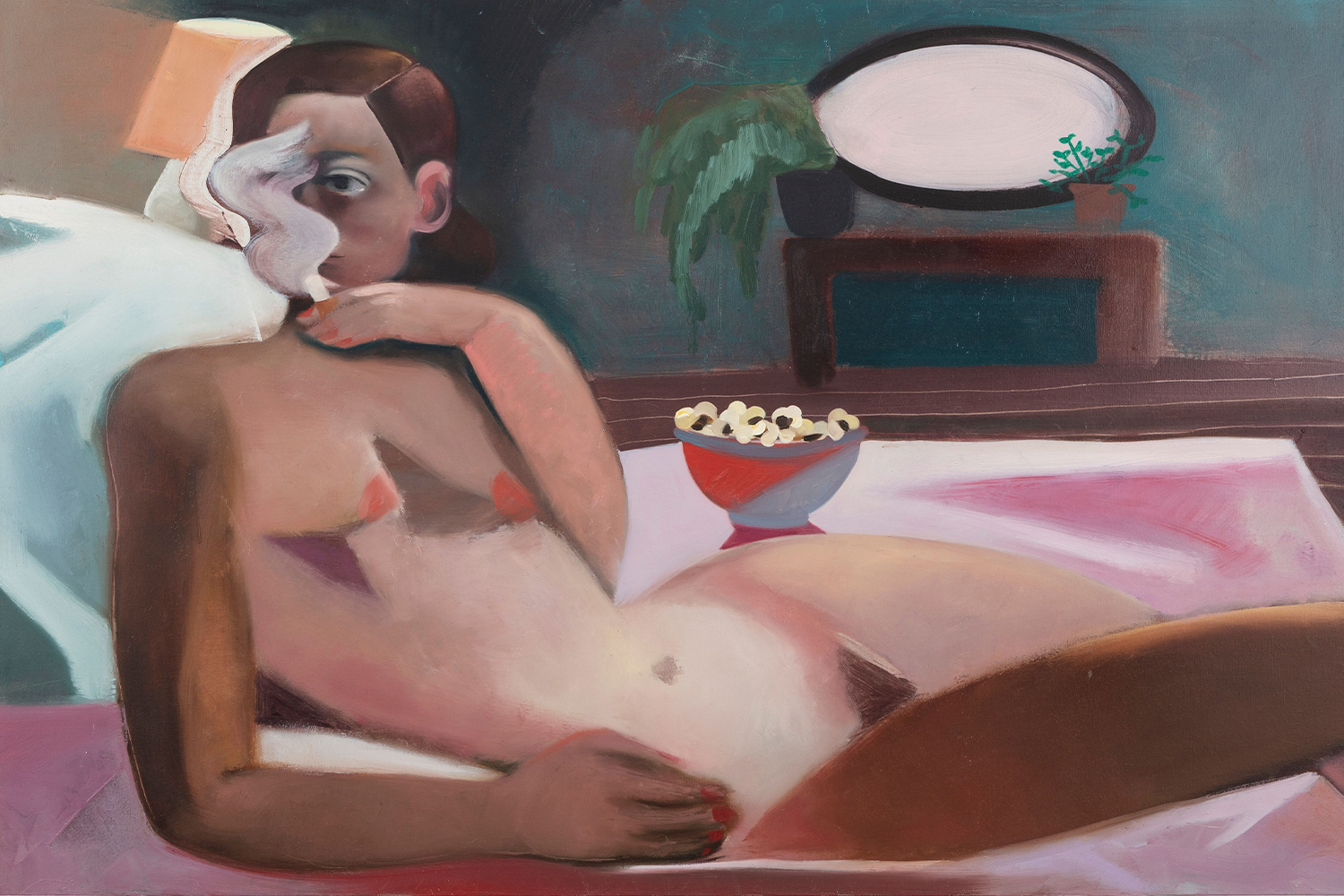

The prominence of architectural elements and their treatment through anti-perspective is another striking feature of the series. Works like Old Dixie Down and Clam Chowder, which depict interiors, serve as an architectural counterpoint to Sun Cafe. Equally impressive is Newgate Gap (2024), a vast grotto whose background, treated with sfumato reminiscent of a famous work by Leonardo, seems to be illuminated by sunlight. This creates a flat surface on which elements of silkscreened palm trees are visible, while in the foreground, a cluster of parked bicycles – like the crowds in En Route – again suggests the theme of contemporary overtourism. This also recalls one of Duchamp’s early nonpictorial works, reproduced using a photographic process: Avoir l’apprenti dans le Soleil (1914), which portrays a man on a bicycle struggling uphill – Duchamp’s first entirely flat work.