After attending the preview of Alexandra Metcalf’s current exhibition, “1st Edition,” at Ginny on Frederick in London, I asked a friend who had accompanied me for his thoughts on the show. “I love it,” he replied without hesitation. “It’s like a teenage girl’s bedroom. It’s so emo.” Having weathered adolescence during the early aughts, when the term “emo” first sprouted into existence, I could relate, as I had been, in many ways, that “emo teen girl” of the very kind my friend was referencing.

Since her arguable breakout show at New York’s 15orient in 2023, many have linked Metcalf’s work to female psychology, and, more expressly, to the often minimize suffering of women. While these interpretations are indeed accurate, they somewhat simplify a more complex practice in development. At its most overt, Metcalf’s installations, sculptures, and paintings engage with a long tradition of dissecting the overlooked experience of what it means to painfully exist as a woman in the modern Western world. For instance, this latest London show draws partial inspiration from 1960s paper dresses, a fashion trend initiated by American designer Harry Gordon. This trend targeted girls, preying upon internal insecurities and external pressures. The specific style led to the concept of the “poster dress” just as adolescence was deemed a significant life phase and pre-empted the charged women’s movement of the 70s.

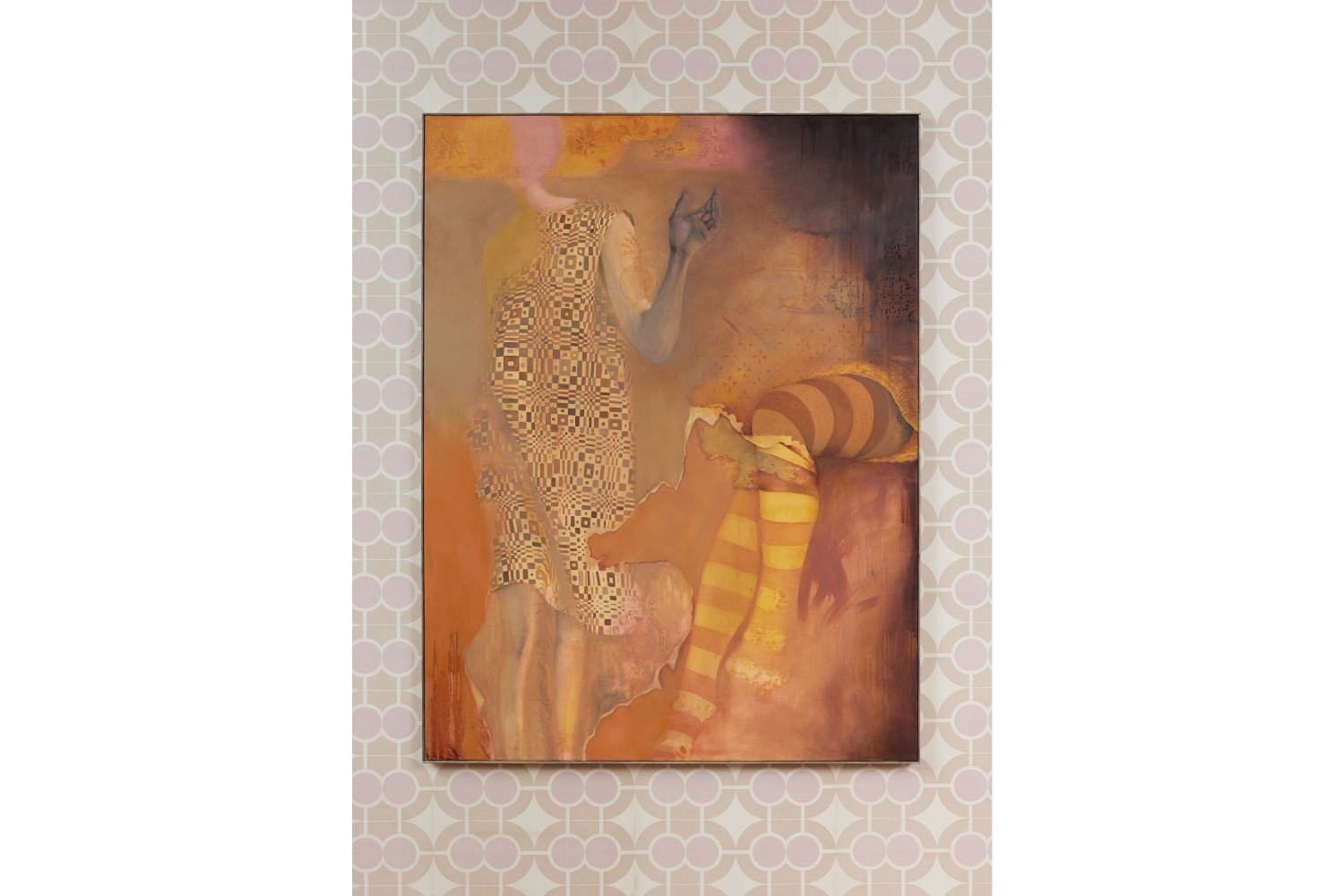

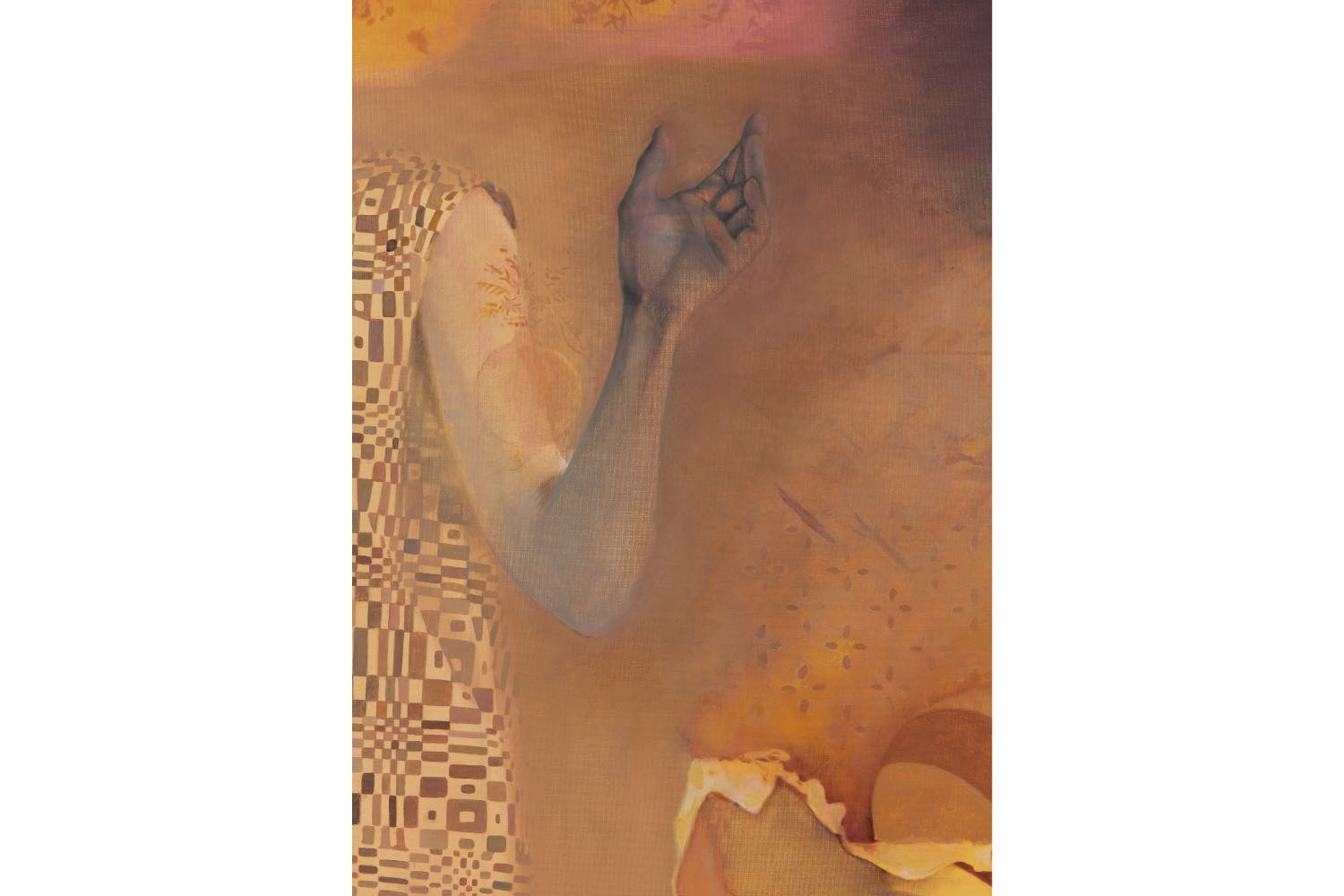

The four paintings on view, varying in size from the substantial to the compact, are rife with Metcalf’s now-signature motifs of infants and historically prominent divas. Notably, the fabled opera singer Maria Callas, an object of both international adoration and criticism in the 1940s and 50s, is a regular fixture found in Metcalf’s work overall.

These newest compositions, made from oil and decoupage on linen, are set within a larger installation featuring patterned wallpaper and centred around a wooden spiral staircase. Together, these elements coalesce in bearing the aura of an angst-ridden pubescent girl’s bedroom. The staircase is the crowning feature, reflecting Metcalf’s ongoing use of wood – a material over which she commands notable prowess – whilst augmenting her conceptual interests: the sinuous staircase, seemingly aged in quality and ascending to nowhere in this backdrop, recalls the trope of the mad woman in the attic.

The press release cites The Yellow Wallpaper, Charlotte Perkins-Gilman’s 1982 short story about supposedly hysterical woman, considered a canonical text of feminist literature. Not only does this exhibition engages with existing arguments in this specific genre through Metcalf’s pointed use of wallpaper but also echoes more recent predecessors, including Joanne Greenberg’s semi-autobiographical I Never Promised You a Rose Garden (1964), Elizabeth Wurtzel’s 1994 Prozac Nation, or the 90s feminist zines Metcalf also employs as source material.

It is a chronic condition of contemporary society to castigate ourselves and our former teen counterparts for expressing unbridled emotion. At the same time, “emo” has needled its way back into the mainstream. The Atlantic, perhaps slightly ahead of the curve, heralded its comeback in 2015 with the article, “Dashboard Confessional, or When It Was Cool to Have Feelings.”1

While the common interpretation of Metcalf’s work as a facet of feminist thought has obvious and indisputable merit, I’d argue that in considering such weighty subject matter, Metcalf is making work that focuses on this topic whilst also embodying a more general cultural shift: that of a return to the emotions of human experience, propped up cherishing teenagerhood. Adolescence is a time when you’re permitted to feel the scope of human emotion in the extreme form, an experience that is arguably endured but only periodically socially accepted throughout life.

As such, assertions limiting the work to its female bent might inadvertently undermine what makes Metcalf’s work in particular forcefully distinct from others currently concerned with the same topic. She is perhaps making tangible the motion of the moment, both leaning into the female angle whilst restaging past eras in which emotions were tolerated yet simultaneously commenting on the resurgence of that same cultural sentiment. This is why the work is so easy to connect with, why my male friend so naturally understood this undertone based on gut and instinct alone, regardless of its marked female flourish.

While Metcalf fully immerses herself in the prickly, inherently emotion-laden territory of female adolescence that shapes a woman’s personhood, she also addresses the universal human experience that transcends gender. During the fragile years of adolescence, we are defined by nothing but our vulnerabilities – a condition that lingers well into adulthood and is central to moving through the world at all.